Brut Chronicle facts for kids

The Brut Chronicle, also known as the Prose Brut, is a collection of old stories about England's history. These stories were first written in a language called Anglo-Norman. Later, they were translated into Latin and English.

The earliest Anglo-Norman versions of the Brut finished around the year 1272, when King Henry III died. Later versions added more to the story. Today, we still have about 50 Anglo-Norman versions. There are also 19 Latin versions, and many of these were then translated into Middle English.

In fact, there are over 180 English versions of the Brut Chronicle! This huge number shows how popular it was. It was one of the most widely read books in Middle English, besides the Wycliffe's Bible. The many copies also show that more people were learning to read in the late Middle Ages.

There are also Welsh versions of these stories, called Brut y Brenhinedd. They are based on an even older text by Geoffrey of Monmouth.

Contents

What is the Brut Chronicle?

The Brut Chronicle started as a legendary history written in the 1200s. It told the story of how Britain was supposedly settled by Brutus of Troy. He was said to be the son of Aeneas, a hero from ancient Troy. The chronicle also covered the rule of Cadwaladr, a Welsh leader.

The Brut was inspired by a text from the century before, written by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It included tales of famous kings who later became legends. These include King Cole, King Leir (who inspired Shakespeare's play King Lear), and the legendary King Arthur.

Early versions of the Brut described England as being divided by the River Humber. The southern part was seen as "the better part." The chronicle was written when there was tension between the king and the nobles. It often showed sympathy for the nobles. It was likely written by clerks who worked for the king, but it wasn't an official history. Later, monks used it for their own chronicles. The Brut was very popular and might have even stopped other histories from being widely read.

Over the centuries, the Brut was changed and updated many times. From 1333, it started including parts of a poem called Des Grantz Geanz. This poem described how England, then called Albion, was settled. The latest known version of the Brut ends with events from 1479. Along with another popular history called the Polychronicon, the Brut was one of the most important histories in 1300s England.

English versions of the Brut appeared in the early 1400s. The most common one is called the "Common" version. It was probably copied in Herefordshire. Later versions from the 1400s added more stories, sometimes with new introductions and endings. In the 1500s, shorter versions were also made.

Who Read the Brut Chronicle?

At first, the Brut was mostly read by the upper-class gentry and English nobility. But as more stories were added and it was changed, other people started to notice it. First, it was translated into Latin for the clergy (church leaders). Then, it was translated into French and English, making it available to the lower gentry and merchant classes.

This meant that many people in English society could read the Brut. As one historian, Andrea Ruddock, said, it was available to the entire political class. Also, if just one person in a household could read, they could share the stories with everyone else. This means the Brut could have reached even more people.

The quality of the surviving copies varies a lot. This suggests that different kinds of people owned and read them. The Brut has been called a "tremendous success" and one of the most copied histories of the 1200s and 1300s.

A version made in York in the late 1300s used official records from that time. For example, it includes an eyewitness account of the Good Parliament of 1376. Versions written after 1399 often favored the Lancaster family. They focused on King Henry V's victories in France, like the Siege of Rouen. This was done for propaganda purposes.

However, even these later versions still included many of the older legendary tales. For example, the story of Albina, a mythical founder of Britain, was still popular. The prose versions of the Brut were very enthusiastic about these legendary parts of English history. It has also been described as a good record of rumors and propaganda, even if not always of the events themselves.

How the Brut was Published

There are about 50 versions of the Brut in Anglo-Norman, found in 49 different manuscripts. There are also 19 Latin translations. Some of these Latin versions were then translated into Middle English. We have at least 184 English versions in 181 medieval and later manuscripts. This is the highest number of copies for any Middle English text, except for Wycliffe's Bible.

From the 1400s, there are also many notes and early drafts related to the Brut. The English edition of the Brut was the first history written in English since the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in the 800s.

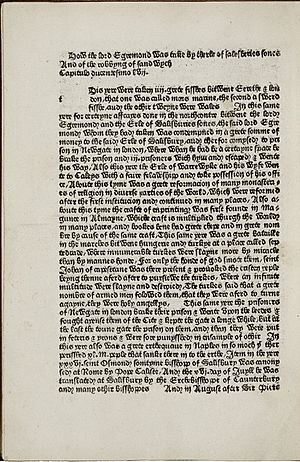

Many copies of the Brut were made by hand. Over 250 manuscripts still exist today, which is a huge number for a medieval text! After all this copying, the Brut was the first history to be printed in England. William Caxton printed it as one of his very first books. He might have even put together this printed version himself.

Caxton printed it as the Chronicles of England in 1480. Between then and 1528, it was printed 13 more times. This shows how important the Brut was. Historian Matheson said that in the late Middle Ages, the Brut was the main history book for British and English history.

Later historians like John Stow, Raphael Holinshed, and Edward Hall used the Brut a lot. Because of this, William Shakespeare also used information from the Brut for his plays.

Anglo-Norman Versions

The Anglo-Norman text was first made for upper-class people who were not church leaders. Some important people who owned copies of the Brut include Guy de Beauchamp, 10th Earl of Warwick and Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln. Isabella of France, a queen, gave a copy to her son, Edward III of England. Thomas Ughtred, 1st Baron Ughtred left his copy to his wife in his will.

Copies were also found in the libraries of religious houses. These include Fountains Abbey, Hailes Abbey, Clerkenwell Priory, and St Mary's Abbey, York (which had two copies!). Some copies were even made in other countries like France and Flanders.

Middle English Versions

The Middle English translations of the Brut reached a wider audience, including the merchant class, not just the upper class. For example, the father of John Sulyard, a landowner, owned a Middle English copy. He passed it on to Henry Bourchier, 2nd Earl of Essex's son, Thomas.

John Warkworth of Peterhouse, Cambridge, owned a copy that included his own Chronicle. Religious houses like St Bartholomew-the-Great and Dartford Priory also owned copies. Historians have even found that several women owned and read the Brut. These include Isabel Alen, Alice Brice, Elizabeth Dawbne, and Dorothy Helbartun.

Why the Brut is Important Today

The Brut is important because it was written by ordinary people, for ordinary people. Also, the later parts of it were some of the first histories written in the English language. Sometimes, it even gives historical details that are not found in other writings from that time.

For example, the Mortimer family owned a Brut in the late 1300s. It included their own family tree, which they traced back to the legendary King Arthur and Brutus.

The first scholarly edition of the later medieval part was published in 1856 by J.S. Davies. In 1879, James Gairdner published parts about the Hundred Years' War. In 1905, C.S.L. Kingsford published three versions in his Chronicles of London. The next year, F.W.D. Brie made a list of all the copies that still exist.

See also

- Gregory's Chronicle

- A Short English Chronicle

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |