Cady Noland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Cady Noland

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | 1956 (age 69–70) Washington, D.C., US

|

| Education | Sarah Lawrence College |

| Known for | |

|

Notable work

|

|

Cady Noland (born 1956) is an American sculptor, printmaker, and installation artist. She often uses everyday objects and images she finds. Her art frequently includes items that suggest danger, industry, or American pride.

Noland's work explores ideas like the challenges of the the American Dream, the difference between being famous and unknown, and violence in American society. Many of her pieces use physical barriers like fences or metal poles to guide or limit how people move through a gallery. She often uses images from news and celebrity magazines, featuring famous people, public figures, and those involved in scandals. Art critic Peter Schjeldahl called Noland "a dark poet of the national unconscious."

Noland has shown her art in major exhibitions, including the 44th Venice Biennale (1990) and the Whitney Biennial (1991). After showing her work widely in the 1980s and 1990s, she mostly stopped exhibiting for almost 20 years. She began showing her art again in the late 2010s, with a museum show in 2018 and new works in the early 2020s. Critics say her unique, sprawling installations have influenced many other artists since the 1990s.

She is also known for disagreements with museums, galleries, and collectors about how her art is handled. Noland has had legal disputes when she said artworks were no longer genuine because of damage or repairs. She has sometimes asked for her work to be removed from group shows. She has also required art dealers to put up notices at unauthorized exhibitions, stating she did not agree to participate. Noland is also very private and has only allowed two photos of herself to be publicly shared.

Contents

Early Life and Art Education

Cady Noland was born in 1956 in Washington, D.C. Her parents were Kenneth Noland and Cornelia Langer.

Her father, Kenneth, was a famous abstract painter. Her mother, Cornelia, was also an artist and co-owned a shop. Her parents divorced in 1957. Kenneth moved to New York City, and Cornelia later remarried. Cady Noland has said that growing up around her father's art practice helped her understand the art world early on.

Noland attended Sarah Lawrence College, her mother's college. After graduating, she lived in Manhattan.

Artistic Journey and Career Highlights

Starting Out: 1980-1987

Cady Noland first showed her art in 1981 in a group exhibition in New York. She started making art with found objects in 1983. One of her early works was Total Institution (1984), a sculpture made from items like a phone and a toilet seat.

In 1987, Noland exhibited several found object artworks at Peter Nagy's gallery, Nature Morte. One piece, Shuttle, featured shiny car parts on an old, rusted cart. The cart was attached to a wall railing, so it couldn't move freely. She also showed Mirror Device, a small mirror piece with a bright orange flare gun and handcuffs. During this time, Noland met artist Steven Parrino, and they became friends.

Also in 1987, Noland gave a lecture called "Towards a Metalanguage of Evil." In this talk, she discussed her research into human behavior, focusing on what she saw as violence and exploitation by successful American men.

Becoming Known: 1988-1989

In 1988, Noland showed photos of her art to Bill Arning, the director of White Columns gallery. Arning was fascinated by her installations, which looked more like collections of objects than traditional art. He invited her to have her first solo exhibition at White Columns.

Noland's show, White Room: Cady Noland, opened in March 1988. Her works used medical items like IV bags and walkers, and industrial materials like rubber mats. She also included a silk screen image of a pistol. Noland even installed a metal bar across the doorway, making visitors duck to enter. The exhibition was praised by critics, and Noland soon received invitations for other major shows. In November 1988, she had her first solo exhibition outside the U.S. in Rotterdam.

In April 1989, Noland had a solo show at American Fine Arts Co. gallery. Many works focused on the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. She silk screened historical images, like Lincoln's boots and the cot he died on, onto metal panels. She also showed Our American Cousin, a metal enclosure filled with empty beer cans, walkers, handcuffs, and a barbecue grill. This work was named after the play Lincoln was watching when he was shot. Other installations included Celebrity Trash Spill and The American Trip, which featured an American flag. Noland also used metal bars to block parts of the gallery, controlling where visitors could go.

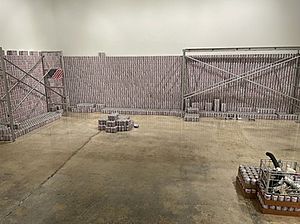

In October 1989, Noland created This Piece Has No Title Yet at the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh. This famous, room-sized installation used over 1000 six-packs of Budweiser beer stacked behind metal scaffolding. American flags, handcuffs, and other items were scattered around. Noland said the beer cans were like a "flag" because of their colors and represented mass production. A curator called the work "jaw-dropping," and it was later purchased by a collector.

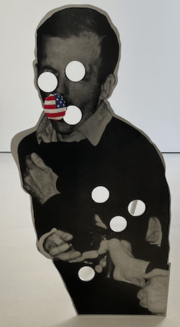

In December 1989, Noland had a solo show in Milan, Italy. She filled the gallery with objects like beer cans, walkers, and a revolver. The largest work, Deep Social Space, included beer cans, an American flag, and a barbecue grill, arranged between metal bars. She also showed many silk screened works with images of kidnapping victim Patty Hearst. Noland also debuted Oozewald, a metal cut-out of Lee Harvey Oswald (who assassinated John F. Kennedy). Noland cut holes in the image and put an American flag into Oswald's mouth. She again used metal bars to guide viewers through the gallery.

Noland also published an essay version of "Towards a Metalanguage of Evil" in a Spanish magazine. The essay included illustrations of other artists' works and photos of car crashes. She later said the essay criticized "a model of the entrepreneurial male whose goals excuse any and all sorts of egregious behavior."

Noland once said that an art dealer tried to censor her work in the late 1980s. For a group exhibition, she installed a metal pole with a small, cut American flag. The dealer reportedly removed it, saying it would offend collectors.

International Recognition: 1990-1992

Noland's work was featured in the 44th Venice Biennale in May 1990. She exhibited Deep Social Space and several silk screened works with images of Oswald, Hearst, and cowboys. Critics noted the "melancholic" effect of her art.

In July 1990, Noland had a solo show in Los Angeles called New West-Old West. The exhibition included a log cabin facade, a chuckwagon, and cut-out images of cowboys. She also showed silk screened panels with images of Mary Todd Lincoln and texts about Colt guns. The gallery staff even wore cowboy outfits and answered the phone saying "howdy." Noland said the outfits were like an "alternative performance." Critics described the show as a "wild ride through the junked landscape of America."

Noland was careful about who bought her art. For her Los Angeles show, collectors had to sign a contract saying she would be involved in any future sale of the work. In 1992, she created a contract that required 15% of future sale profits to go to a homelessness prevention charity.

In August 1990, Noland participated in a group exhibition called Just Pathetic. She showed assemblage works like Pedestal (1985), which looked like a potted plant, and Chicken in a Basket (1989), a shopping basket with a rubber chicken and a crumpled American flag.

In 1991, Noland was part of the Whitney Biennial, where she installed This Piece Has No Title Yet. She also showed her silk screen works of Oswald and Hearst. Her installation was very talked about, with some critics calling her a star of the exhibition and others not liking it.

In February 1992, Noland created a special installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA). She attached blurry copies of images to the walls, placed paint buckets around the room, and used chain-link fences and steel blockades. She also left scuff marks and drill holes on the gallery walls.

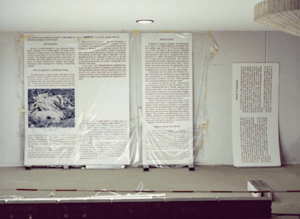

Noland was chosen to exhibit at Documenta 9 in June 1992 in Kassel, Germany. She presented a 3D version of her essay "Towards a Metalanguage of Evil." Passages from the text were silk screened onto boards placed in an underground parking garage. She added a section called "The Bonsai Effect" that criticized American excess. Noland also included artworks by other artists and surrounded her installation with cinder blocks and a car. A co-director of Documenta said Noland's choice to install her show in a parking garage was "quite shocking."

Museum Shows and New Works: 1993-1999

In 1993, Noland had a two-artist exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art. She made silk screen works on reflective metal surfaces, which she called "funhouse mirrors." She also asked the museum to provide wheelchairs for visitors, saying they allowed people to move if they wanted to. In 1993, she also started making large silk screen works of red brick walls.

For a solo exhibition in 1994 at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York, Noland created four sculptures that looked like old-fashioned stocks. These sculptures were interactive, and viewers could lock themselves in them. Noland believes stocks were an early form of public sculpture in colonial America. She also presented Publyck Sculpture, a set of wooden beams with three tires hanging like a swing set. This piece was inspired by a tire swing found near a controversial group leader's hiding place.

Noland also produced silk screen works featuring images and text from newspapers about public figures involved in controversy. These included Thomas Eagleton, a former politician whose career was affected by health issues; Wilbur Mills, a former politician who resigned after public incidents; Vince Foster, a White House official who passed away after struggling with work-related stress; Martha Mitchell, a whistleblower who was reportedly silenced; and the former husband of a famous actress who protested their divorce. Critics described the exhibition as a "walk-in scrapbook of various crimes, misdemeanors and scandals."

Noland told a curator in 1994 that she wasn't interested in the specific people or events in her works. Instead, she was fascinated by how the media focused on them. She spends many hours in news archives finding material for her art.

In January 1995, Noland participated in an exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. She showed silk screen works of figures from Nixon-era public scandals and Publyck Sculpture. She also exhibited her largest stocks sculpture, Tower of Terror (1993-1994), an all-aluminum piece with enough holes for several people.

In March 1995, Noland had a solo exhibition at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam. She showed silk screened aluminum works with images of Hearst and Foster, along with campaign posters of Hearst's grandfather, William Randolph Hearst, and a photo of First Lady Betty Ford. She also presented two of her stocks sculptures and a tire swing sculpture.

In June 1996, Noland opened a solo exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. She displayed silk screened works on metal, featuring images of Eagleton, Ford, Foster, Holm, Mills, and Mitchell. She also included a controversial figure who attempted to harm a public official, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, President Kennedy's widow. Noland installed metal bleachers for visitors to sit and view the art, like at a sporting event. She also included a tire swing sculpture, My Amusement, and a stocks sculpture called Sham Rage.

Noland also created a special editioned work for Parkett magazine in 1996. The piece, Not Titled Yet, was a cardboard piece with holes, similar to her stocks sculptures.

In 1999, Noland exhibited in a group show curated by artist Robert Gober in New York. Noland presented her first new work in several years, Stand-In for a Stand-In, a version of her stocks sculptures made from cardboard and wood.

Also in 1999, Noland had a two-artist exhibition with Olivier Mosset in Zurich. Noland showed new sculptures made with a-frames, which she used as barricades in the gallery. She also exhibited a large cardboard tube covered with black-and-white logos. She used a chain-link fence to block off parts of the gallery.

Stepping Back: 2000s

After a group exhibition in 2000, Noland largely stopped showing new work or engaging publicly with the art world for over a decade. In the 2000 exhibition, she installed a new a-frame barricade sculpture that almost completely blocked the entrance to the gallery. Noland had instructed the gallery not to sell her work to other art dealers. The work didn't sell, and Noland asked the gallery to get rid of it by placing the a-frames on the street until they disappeared.

In 2003, Noland's work The Big Slide (1989) was included in the Italian pavilion at the 50th Venice Biennale. The same year, a gallery tried to include her work in a group exhibition, but she asked for its removal. In 2004, she wrote an essay for Artforum about artist Andy Warhol, whose work she admires.

Noland's long absence led some galleries to try to put on unauthorized exhibitions. For example, in 2006, a gallery showed remakes of Noland's work made by other artists. Art critics reacted negatively to this, calling it "an aesthetic act of karaoke."

Legal Challenges and a Retrospective: 2010s

In March 2012, an auction house removed Noland's print Cowboys Milking (1990) from a sale after she said the work was too damaged to be repaired. The owner of the work later sued Noland and the auction house, but the lawsuit was dismissed.

Also in 2012, galleries began posting disclaimers at Noland's request when exhibiting her work for sale. These notices informed audiences that Noland had not been involved with or approved the exhibition.

In 2013, art dealer Larry Gagosian tried to organize an exhibition of Noland's work. Noland reportedly strongly expressed her disapproval, saying she didn't want to be "saved from obscurity." She also told an author that dealing with unauthorized exhibitions and restorations was "a full-time thing" that affected her ability to make new art.

In June 2015, a collector filed a lawsuit to reverse his purchase of Noland's sculpture Log Cabin (1990) for $1.4 million. He claimed Noland had disavowed the work because it had been extensively restored without her approval. The restoration happened after the logs deteriorated from being outdoors for 10 years. Noland felt the restored piece was essentially a new, unauthorized copy. However, the lawsuit was dismissed. The United States Copyright Office later ruled that Log Cabin was not eligible for copyright protection because it "lacked sufficient original or creative authorship."

In November 2017, a gallery opened an exhibition of historical work by Noland and Alexander Calder, with Noland's permission. The show, Kinetics of Violence: Alexander Calder + Cady Noland, featured two works by each artist. Noland exhibited Corral Gates (1989), a series of gates decorated with saddles and bullets, and Gibbet (1993-1994), a stocks sculpture with an American flag.

After almost two decades of little public activity, Noland had her first museum retrospective exhibition in 2018 at the Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK) in Frankfurt, Germany. The curator convinced Noland to participate, and they planned the show closely for a year using scale models, as Noland has a fear of flying. Noland's work was installed throughout the museum, even in hallways and corners. The exhibition also included works by other artists chosen by Noland. The retrospective was widely praised.

Noland also agreed to participate in a group exhibition in October 2019, curated by artist Paul Pfeiffer. The show was held in an empty bank at Washington's Watergate complex. It included a chain-link fence sculpture by Noland, Institutional Field (1991), placed flat on the floor.

New Work in the 2020s

In 2021, Noland exhibited new work in New York for the first time in over twenty years. Her exhibition Cady Noland: THE CLIP-ON METHOD at Galerie Buchholz featured four a-frame barricade sculptures and two chain-link fence sculptures. She also covered the gallery floor with a gray carpet and showed silk screen works from the 1990s. Critics noted the strong chemical smell from the new carpet. The exhibition coincided with a book she published documenting her works and writings.

Noland presented new work again in 2023 at a solo exhibition with Gagosian Gallery in New York. This was a decade after she had refused Gagosian's earlier attempts to show her work. The exhibition included new untitled works made from objects like filing cabinets, lucite tables, beer cans, bullets, and police badges. She also showed an older work, Untitled (1986), a metal walker with leather gloves. One critic noted that tape on the floor made the installation look like a crime scene. The entire exhibition was purchased by the private museum Glenstone.

In October 2024, Glenstone mounted a survey of Noland's work, created "in collaboration with the artist." The show included works from Glenstone's collection from all periods of Noland's career, including the pieces from her 2023 Gagosian show. Noland also installed new objects around her recent work, such as industrial plastic pallets and a metal platform with an Amazon warehouse barcode. A critic called the show, along with her other recent exhibitions, her "comeback tour."

Impact and Legacy

Many critics, art historians, and artists say Cady Noland has greatly influenced contemporary art since the 1990s. Critic Roberta Smith has written that Noland helped define a style for installation artists of the 1990s, using "junk and juxtaposition." Smith said Noland's contribution is "unquestionable."

In 2007, New York magazine called Noland "The most radical artist of the eighties" and said her work "predicted a hundred other artists." Critics have named many artists who work in a similar style to Noland. Artists like Mary Heilmann and Josephine Meckseper have also said Noland inspired their work.

Curator Bill Arning said in 2018 that his students "shero worship" Noland. They admire her strong decision-making and her ability to say no to fame and money.

Personal Life

Cady Noland is very private about her early life and personal details. There are only two known public photographs of her as an adult. In one photo from Documenta in 1992, she is covering her face with her hands. When asked for photos for publications, she has sometimes sent pictures of herself as a child instead of current ones.

Art Market Success

In 2011, Noland's work Oozewald (1989) sold for $6.6 million at Sotheby's. This set a record at the time for the highest price paid for an artwork by a living woman. In May 2015, her red silk screen on aluminum, Bluewald (1989), also depicting Oswald, sold for $9.8 million at Christie's. This set a new auction record for her work.

Exhibition Highlights

Cady Noland has had many solo exhibitions in the U.S. and internationally. She showed a lot of work in the late 1980s and early-mid 1990s, then stopped exhibiting for almost 20 years.

Notable solo exhibitions include:

- White Room: Cady Noland (1988), White Columns, New York

- New West-Old West (1990), Luhring Augustine Hetzler, Los Angeles

- Cady Noland (1994), Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

- Cady Noland (2018-2019), Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt (her first major retrospective)

- Cady Noland: THE CLIP-ON METHOD (2021), Galerie Buchholz, New York (her first exhibition of new work in the U.S. in over twenty years)

- Cady Noland (2023), Gagosian Gallery, New York

She has also participated in many important group exhibitions, such as:

- The 44th and 50th Venice Biennale (1990, 2003)

- Whitney Biennial (1991)

- Documenta 9 (1992)

Art in Public Collections

- The American Trip (1988), Museum of Modern Art, New York

- The Big Slide (1989), Art Institute of Chicago

- Celebrity Trash Spill (1989), Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, Vaduz

- Deep Social Space (1989), Museum Brandhorst, Munich

- Oozewald (1989), Glenstone, Potomac, Maryland; and Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp

- Tanya as a Bandit (1989), Museum Brandhorst, Munich; Museum of Modern Art, New York; and Whitney Museum, New York

- This Piece Has No Title Yet (1989), Rubell Museum, Miami/Washington, D.C.

- Bluewald (1989-1990), Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut

- Sham Death (1993-1994), The Broad, Los Angeles

- Publyck Sculpture (1994), Glenstone, Potomac, Maryland

- 4 in One Sculpture (1998), Hessel Museum of Art, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York

- Untitled (2008), Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

Images for kids

-

Our American Cousin (1989) at Glenstone.

-

This Piece Has No Title Yet (1989) at the Rubell Museum.

-

Oozewald (1989) at Glenstone.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |