Cassiopeia A facts for kids

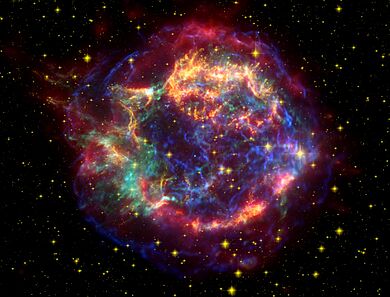

This colorful image combines views from three different telescopes. Red shows infrared light (heat) from the Spitzer Space Telescope, gold is visible light from the Hubble Space Telescope, and blue/green is X-ray light from the Chandra X-ray Observatory. The tiny blue dot near the center is what's left of the star's core.

|

|

| Event type | Supernova |

|---|---|

| IIb | |

| Date | 1947 by Martin Ryle and Francis Graham-Smith) |

| Duration | Lua error in Module:WikidataIB at line 168: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| Instrument | Lua error in Module:WikidataIB at line 168: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| Constellation | Cassiopeia |

| Right ascension | 23h 23m 24s |

| Declination | +58° 48.9′ |

| Epoch | J2000 |

| Galactic coordinates | 111.734745°, −02.129570° |

| Distance | c. 11,000 ly |

| Redshift | Lua error in Module:WikidataIB at line 168: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| Remnant | Shell |

| Host | Milky Way |

| Notable features | Strongest radio source beyond the Solar System |

| Peak apparent magnitude | c. 6 |

| Other designations | Lua error in Module:Wikidata at line 132: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| Preceded by | SN 1604 |

| Followed by | G1.9+0.3 (unobserved, c. 1868), SN 1885A (next observed) |

Cassiopeia A (or Cas A) is the glowing remains of a giant star that exploded. This is called a supernova remnant. It is located in the constellation Cassiopeia, about 11,000 light-years away from Earth in our own Milky Way galaxy.

Cas A is special because it's the brightest object in our sky that we can see with radio telescopes, except for our own Sun. The cloud of gas and dust from the explosion is still expanding and is now about 10 light-years wide.

Scientists believe the light from this supernova first reached Earth around the 1660s. However, no one wrote about seeing a bright new star back then. This is likely because clouds of interstellar dust blocked the view, making it hard to see with the eyes.

Contents

A Star That No One Saw Explode

By studying how fast the cloud is expanding, astronomers calculated that the explosion should have been visible from Earth around the year 1667. A supernova this close would normally be very bright in the night sky.

One astronomer, John Flamsteed, might have seen it in 1680. He recorded a faint star, but its position in his notes doesn't quite match where Cas A is. It's possible he made a small mistake in his measurements.

Because there are no clear records, it remains a mystery. A bright new star in Cassiopeia would have been visible for months, so it's strange that it was missed. Because of this, no supernova in our Milky Way galaxy has been clearly seen by the naked eye since the invention of the telescope.

An Expanding Cloud of Star Stuff

The shell of material blown off by the star is incredibly hot, about 30 million K. The Kelvin scale is a temperature scale used by scientists. This cloud is also moving at an amazing speed of 4,000 to 6,000 kilometers per second. That's fast enough to travel across the United States in less than a second!

Pictures from the Hubble Space Telescope show that the explosion wasn't a perfect sphere. Instead, it shot out two powerful jets of material in opposite directions. These jets are moving even faster, up to 14,500 km/s. When scientists use colors to map out the different chemical elements in the cloud, they can see that materials from the original star are still grouped together.

Seeing in Radio Waves and X-Rays

Cas A was one of the first objects in space found using radio telescopes, back in 1948. It shines very brightly in radio waves, which are a type of light our eyes cannot see. However, as the remnant cools down over thousands of years, its radio signal is slowly getting weaker by about 1% each year.

Cas A also glows brightly in X-rays, another high-energy form of light. In 1999, the Chandra X-Ray Observatory looked at the center of the remnant. It found a tiny, super-dense object called a neutron star. This is the crushed core of the star that exploded.

A Ghostly Echo of Light

In 2005, the Spitzer Space Telescope saw something amazing: a "light echo" from the supernova. This is like a sound echo, but with light. The bright flash from the explosion traveled through space, bounced off nearby dust clouds, and that reflected light is only now reaching us, centuries later.

By studying the light from this echo, astronomers figured out exactly what kind of star exploded. It was a Type IIb, which comes from a massive star called a red supergiant. This star had already blown away most of its outer hydrogen gas before it finally exploded. This was the first time scientists could study a supernova by its echo, allowing them to look back in time at cosmic events.

A Factory for Life's Building Blocks

Phosphorus is a chemical element that is essential for all life on Earth. It's a key part of our DNA. In 2013, astronomers used telescopes to study the material in Cas A and found large amounts of phosphorus. The amount of phosphorus compared to iron was up to 100 times higher than what is normally found in our galaxy.

This discovery helped prove that supernovae are like cosmic factories. They create heavy elements, including the ones needed for life, and spread them across the galaxy. This material can then form new stars, planets, and maybe even life.

Gallery

-

The infrared echo caused by the Cassiopeia A supernova seen by Spitzer. The image was processed in a way that the infrared echo appears colored while dust clouds remain grey. North is on the left.

-

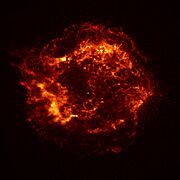

Cassiopeia A seen by the 24-inch Ritchey-Chrétien reflector at the Mount Lemmon Observatory

-

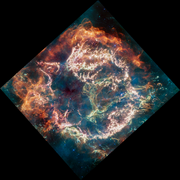

Cassiopeia A was the first light image of the Chandra X-ray Observatory

-

Cassiopeia A observed by the JWST's Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI)

-

Cassiopeia A seen by Spitzer and showing different chemical elements and dust within the supernova remnant

See also

- List of supernova remnants

- Light echo

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |