Mines of Paris facts for kids

The Mines of Paris are a huge network of old, abandoned underground tunnels and rooms beneath the city of Paris, France. People often call them the "quarries of Paris" in French. These mines were dug to get out stone and other materials used to build the city above.

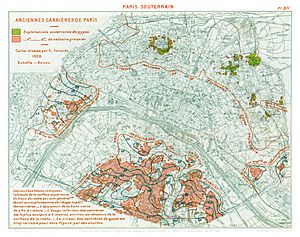

There are three main parts to this underground world. The biggest one, called the "large south network," is under several areas of Paris (the 5th, 6th, 14th, and 15th districts). There's another network under the 13th district and a third under the 16th. Smaller tunnels exist in other places too.

Miners mainly dug for Lutetian limestone, which was a popular building material. They also extracted gypsum, which is used to make "plaster of Paris" (the stuff used for casts and sculptures).

It's actually against the law to explore most of these mines without permission. If you get caught, you can face big fines. But even with these rules, many urban explorers, known as cataphiles, love to visit these hidden tunnels.

A small part of this underground network, about 1.7 kilometers (1.1 miles) long, is used as an ossuary. This means it's a place where human bones are stored. This famous part is known as the Catacombs of Paris. You can visit some parts of the Catacombs legally. Many people mistakenly call the entire underground network "the Catacombs," but only a small section is actually used for bones.

Contents

How Paris's Underground Rocks Formed

Paris sits in a giant bowl-shaped area called the Paris Basin. This shape was created over millions of years by ancient seas and by water wearing away the land. For a very long time, much of what is now northwestern France was covered by seawater. Over time, this area slowly rose.

The Paris region experienced many cycles of being covered by sea water, then by calm lagoons, and sometimes by fresh water. Rivers and wind also shaped the land. These changes created many different layers of rock, full of minerals that became very important for Paris's growth.

Minerals from Ancient Seas

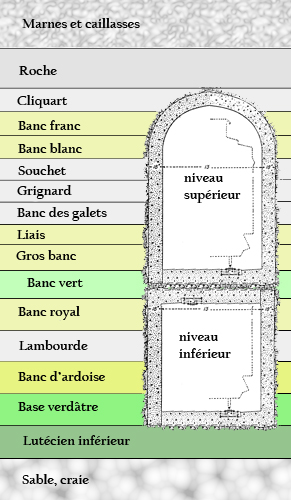

Because Paris was mostly underwater for so long, it has many layers of sedimentary rock. These are rocks formed from bits of sand, mud, and dead sea creatures that settled at the bottom of the water. One of the most important rocks found here is Lutetian Limestone.

Millions of years ago, during the early Cretaceous period, the Paris area was a flat seabed. First, it was a deep ocean, then a shallower sea closer to the shore. Over time, tiny bits of silica (like sand) settled and, under pressure, turned into a thick layer of clay. Later, seas rich in calcium covered this clay with an even thicker layer of chalk.

Paris eventually rose out of the sea. Huge movements of the Earth's crust created hills and valleys across the Paris Basin. These conditions were perfect for new mineral deposits to form in the next eras.

After another long period above sea level, Paris began to switch between being land and sea. It became a place with calm bays and lagoons, full of tiny sea creatures that had shells made of silica. When these creatures died, their shells mixed with other deposits on the lagoon floor. Pressure and water chemicals turned this mix into a special type of sedimentary stone called calcaire grossier (or calcaire lutécien). The most important deposits of this stone happened during the Eocene epoch. In fact, this geological age is named Lutetian because Lutetia was the Roman name for Paris!

Another important mineral deposit in Paris came later, during the Bartonian age. After periods where sand and lower-quality limestone layers formed, the sea pulled back. It only returned sometimes to fill lagoons with seawater. When these lagoons dried up, the salts in the water, mixed with other materials, crystallized into gypsum. Gypsum is the main ingredient in plaster of Paris.

This drying-up process happened many times, creating several layers of gypsum separated by layers of other minerals left by the sea's brief returns. In Paris, there are four main layers of gypsum. The highest and most important one, called the haute masse, was the most mined. Gypsum is quite fragile and can easily dissolve if fresh water gets into it.

The sea returned to the Paris Basin one last time towards the end of the Paleogene period. It left several layers of different sediments, topped with a thick layer of clay. This final clay layer was very important. When the Paris Basin finally rose from the sea for good, this top layer protected the soft, soluble gypsum layers from being washed away by rain and wind.

How Rivers Shaped the Land

Paris started to look like it does today as huge rivers, formed from melting ice ages, carved through millions of years of rock layers. They left behind only the parts of the land that were too high or too strong to be worn away. The hills of Montmartre and Belleville are examples of places where gypsum remained. The ancient Seine river, much wider than it is today, once flowed almost along its current path, with many smaller streams branching off.

Mining Methods in Paris

Open-Air Quarries

The simplest way to get minerals was to dig them up from the surface. This happened in places where rivers had worn away the land, exposing different rock layers. For example, plaster deposits were found on the hills of Montmartre and Belleville. Lower down, near the river valleys, sand and limestone were closer to the surface. Clay layers could be found in the lowest parts of the Seine, Marne, and Bièvre river valleys.

Underground Mining

Digging from the surface became difficult and expensive when the desired minerals were deep underground. Miners would have to remove huge amounts of unwanted dirt and rock first. To avoid this, they started digging horizontally into hillsides where the mineral layers were visible. However, Paris didn't have many places like this, except for gypsum.

By the 15th century, most stone quarries were no longer open-air. Instead, miners would dig vertical wells down to the desired stone layer. From there, they would dig horizontally into the rock. There's even evidence that the Romans used this method to mine clay under the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève hill in Paris.

Pillars of Rock

No matter how miners got underground, they had to make sure the ceiling wouldn't collapse. An early method, popular from the late 10th century, was called piliers tournés (meaning "turned pillars"). Miners would dig a main tunnel, then dig tunnels perpendicular to it, and then more tunnels parallel to the first. This created a grid of untouched rock columns, or "pillars," that held up the mine ceiling. In wider areas, miners would add extra support by building columns of stacked stones called piliers à bras (arm pillars).

Gypsum mines, which produced the famous plaster of Paris, used this method in a special way. Some gypsum deposits in northern Paris were very thick, up to 14 meters (46 feet) deep. Miners would dig their tunnel grids at the top of the deposit, then start digging downwards. When a gypsum mine was empty, it looked almost like a cathedral because of the tall columns and arches left behind. Today, only one example of this kind of gypsum mine remains in Paris, in a renovated "grotto" under the Buttes-Chaumont gardens.

This method worked well for a while. But over time, the soft rock could wear away or crack, making the mine unstable.

Walls and Fillings

Another technique, which appeared around the early 18th century, was called hagues et bourrages (walls and fillings). This method was both more economical and stronger. Instead of just tunneling, miners would start in the middle and dig outwards. When they had removed a lot of stone and the ceiling was unsupported, they would build a line of piliers à bras (stone columns). They would continue digging beyond this line, then build a second parallel line of columns. The space between these two lines of columns was then turned into solid walls using stone blocks, called hagues. The space between these walls was filled with packed rubble and other leftover rock, called bourrage. This method allowed miners to extract much more of the valuable mineral. It also provided a support system that could settle and shift with the mine ceiling, making it more stable.

Paris Built on Hidden Tunnels

We don't have clear proof of mining in Paris before the late 13th century. The first known record from 1292 mentions 18 "quarriers" (people who worked in quarries). The first written permission for a mine dates from 1373, allowing a woman named Dame Perrenelle to operate a plaster mine on her property near Montmartre.

Most of Paris's limestone deposits were on the Left Bank. When the city's population moved to the Right Bank in the 10th century, these mines were far outside the city. As stone from old ruins became scarce in the 13th century, new mines opened further from the city center. Older mines closer to the city were sometimes reused. For example, when Louis XI gave the old Chateau Vauvert (now part of the Luxembourg Garden) to a group of monks in 1259, they turned the underground caverns into wine cellars and continued to dig for stone at the edges of the old mine.

By the early 16th century, stone was being dug near places like the Jardin des Plantes and the Luxembourg Garden. Paris's plaster mines were mostly still on the Right Bank hills of Montmartre and Belleville.

It was only when Paris grew beyond its 13th-century walls (which are now roughly followed by metro lines 6 and 2) that the city started building on top of old mine sites. This led to many cave-ins and other disasters. The Left Bank suburbs were most at risk. In the 15th century, many people built homes in areas like faubourg Saint-Victor, faubourg St Marcel, faubourg Saint-Jacques, and faubourg Saint-Germain-des-Prés, all of which had mines underneath.

Even though the Right Bank of Paris had expanded greatly by the 17th century, the Left Bank was much less crowded within its old, crumbling 13th-century walls. Many royal and church buildings were built there, but it seems people had forgotten about the mines underneath. The Val de Grâce convent and the Observatory, built in the mid-1600s, were found to be sitting on huge caverns left by old stone mines. Reinforcing these mines used up most of the money set aside for these projects.

The suburbs continued to grow along the main roads leading out of the city, especially with more traffic heading to palaces like Fontainebleau and Versailles. The road to Fontainebleau (now Avenue Denfert-Rochereau) was the site of one of Paris's first major mine collapses in December 1774. About 30 meters (100 feet) of the street suddenly fell in, creating a hole about 30 meters deep.

Fixing the Abandoned Mines

The 1774 disaster was a big reason why the King's Council decided to create a special group of architects. Their job was to inspect, maintain, and repair the ground under royal buildings in and around Paris. Another group of inspectors, controlled by the Ministry of Finance, also claimed responsibility for keeping national roads safe.

The Inspection Générale des Carrières (IGC), or General Inspectorate of Quarries, officially started on April 24, 1777. They began work right after another part of the Fontainebleau road collapsed. Even though the Ministry of Finance tried to keep control over damaged roads, the IGC eventually took over because they were much better at the job.

For centuries, most of the mines under Paris had been forgotten and weren't mapped. So, no one really knew how big the network of old mines was. The IGC inspected all important buildings and roads. They looked for any signs of the ground shifting and used tools to find hidden empty spaces underneath. Roads were a particular problem. Instead of just checking the ground around the road, inspectors dug tunnels directly under the road. They filled any empty spaces they found and reinforced the tunnel walls with strong stone to prevent future collapses.

When a section of road was fixed, the date of the work was carved into the tunnel wall underneath it, next to the name of the road above. These tunnel renovations, some dating back to 1777, still show us the old street names of Paris.

Mines Become a Burial Place

During the 18th century, Paris's population grew so much that the city's cemeteries became completely full. This caused serious public health problems. Towards the end of the 1700s, it was decided to create three large new cemeteries outside the city and to move the bones from the old city cemeteries.

Human remains were gradually moved to a renovated part of the abandoned mines. This area eventually became a large ossuary, a place for bones. The entrance to this ossuary is located on the present-day Place Denfert-Rochereau.

The ossuary became a small tourist attraction in the early 19th century. It has been regularly open to the public since 1867. Although its official name is the Ossuaire Municipal (Municipal Ossuary), it is popularly known as "the catacombs." Even though the entire underground network of Paris's mines is not a burial place, the term "Catacombs of Paris" is often used to refer to the whole network.

Related pages

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |