Charles Davenport facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

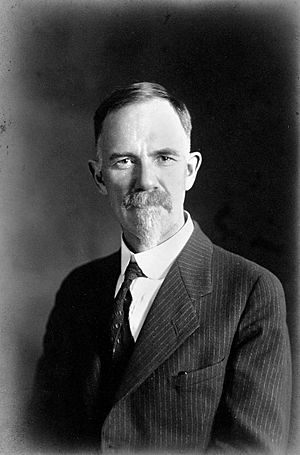

Charles Davenport

|

|

|---|---|

Davenport in c.1929

|

|

| Born | June 1, 1866 |

| Died | February 18, 1944 (aged 77) |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Spouse(s) | Gertrude Crotty Davenport |

| Children | 3 (including Millia Crotty) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Eugenicist and biologist |

| Institutions | Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory |

| Influences | Francis Galton, Karl Pearson |

| Influenced | Wilhelmine Key |

Charles Benedict Davenport (born June 1, 1866 – died February 18, 1944) was an American biologist. He was also a leading figure in the eugenics movement in the United States.

Contents

Early Life and School

Charles Davenport was born in Stamford, Connecticut. His father, Amzi Benedict Davenport, was an abolitionist (someone who wanted to end slavery). His mother was Jane Joralemon Dimon. Charles grew up in Brooklyn Heights, New York.

Because his father had strong beliefs, Charles was taught at home when he was young. This helped him learn about hard work and the importance of education. When he wasn't studying, Charles worked for his father's business. His father wanted him to become an engineer.

But Charles was more interested in science. He saved money and then went to Harvard University. He earned his Bachelor's degree and later a Ph.D. in biology in 1892. In 1894, he married Gertrude Crotty, who also studied zoology at Harvard. They had two daughters.

Career in Science

Later, Charles Davenport became a professor of zoology at Harvard. He became one of the most important American biologists of his time. He helped create new ways to classify living things, called taxonomy.

Davenport admired the work of Francis Galton and Karl Pearson. They studied how living things change over time using math, a method called biometrics. Davenport even helped with Pearson's science journal, Biometrika.

After scientists rediscovered Gregor Mendel's ideas about how traits are passed down (called Mendelian inheritance), Davenport became a strong supporter of these ideas.

From 1899 to 1904, Davenport worked in Chicago. He was in charge of the Zoological Museum at the University of Chicago.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

In 1904, Davenport became the director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. There, he started the Eugenics Record Office in 1910. At the lab, Davenport began studying how human traits like personality and mental abilities were passed down.

He wrote many papers and books about the genetics of things like alcoholism, crime, and intelligence. He also studied the effects of different races mixing. Davenport also helped many students at the Laboratory.

Davenport became very interested in human heredity. Much of his work focused on promoting eugenics. Eugenics was a movement that aimed to "improve" the human race by controlling who could have children.

His 1911 book, Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, was used as a textbook in colleges. The next year, he was chosen to be part of the National Academy of Sciences.

Controversy and Criticism

Davenport's work in eugenics caused a lot of disagreement among other scientists. His ideas were often too simple and didn't match what was truly known about genetics. This led to unfair ideas based on race and social class. Many people, even other eugenicists, didn't see his work as truly scientific.

In 1925, Davenport started the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations (IFEO). He wanted to create a "world map" of "mixed-race areas."

With his assistant Morris Steggerda, Davenport tried to study mixing of human races. Their 1929 book, Race Crossing in Jamaica, claimed to show that mixing white and black populations led to problems. Today, this book is seen as scientific racism. Even at the time, it was criticized for making conclusions that didn't match the facts. For example, Karl Pearson, whom Davenport admired, said the book's samples were too small to be trusted.

The whole eugenics movement was criticized for being based on racist and classist ideas. It tried to prove that many Americans were "unfit" based on their background.

Influence on Immigration Rules

Charles Davenport's ideas also affected rules about immigration in the United States. He believed that a person's race decided their behavior. He also thought that many mental and behavioral traits were passed down from parents. He studied family histories to reach these conclusions. However, some of his fellow scientists said his conclusions were not based on enough evidence.

Davenport believed that differences between races meant that strict immigration rules were needed. He thought people from "undesirable" races should not be allowed into the country. Like many scientists at the time, he considered Black people and people from Southeastern Europe to be "genetically inferior."

He actively tried to influence members of Congress. Charles Davenport often spoke with Congressman Albert Johnson. Johnson was involved in creating the Immigration Act of 1924. Davenport encouraged him to limit immigration in that law.

Davenport was not alone in this effort. Harry H. Laughlin, who was in charge of the Eugenics Record Office, spoke to Congress many times. He promoted strict immigration laws. He believed that immigration was a "biological problem." Davenport's efforts gave a "scientific" reason for social rules he supported, especially regarding immigration.

Later Life and Impact

After Adolf Hitler's rise to power in Germany, Davenport kept in touch with some Nazi groups and publications. This was before and during World War II. He wrote for two important German journals that started in 1935. In 1939, he wrote for a special book honoring Otto Reche, who was important in the Nazi plan to remove "inferior" people in eastern Germany.

Even though many other scientists stopped supporting eugenics because of Nazism, Charles Davenport continued to believe in it until he died. He retired in 1934. Six years later, in 1940, the Carnegie Institute stopped funding the eugenics program at Cold Spring Harbor. But Davenport still held onto his beliefs.

While Charles Davenport is mostly remembered for his role in the eugenics movement, he also helped get more money for genetics research. His ability to find financial support for scientific projects helped him throughout his career. It also allowed other scientists to do their own studies. Many important geneticists worked at Cold Spring Harbor while he was director.

He died from pneumonia in 1944 when he was 77 years old. He is buried in Laurel Hollow, New York.

Davenport's Eugenics Beliefs

Here are some of Charles Davenport's beliefs about eugenics, as written by Oscar Riddle:

- "I believe in trying to make the human race the best it can be in terms of social organization, working together, and being effective."

- "I believe that I am in charge of the genetic material I carry. This has been passed down to me for thousands of generations. I will fail this trust if I do anything to harm it, or if I limit having children for my own comfort, when my genetic material is good."

- "I believe that after choosing a marriage partner carefully, we should aim to have 4 to 6 children. This is so our carefully chosen genetic material will be passed on enough. This preferred group should not be overwhelmed by those less carefully chosen."

- "I believe in choosing immigrants so that our nation's genetic material is not mixed with traits that are not good for society."

- "I believe in controlling my natural urges if following them would harm the next generation."

See also

In Spanish: Charles Benedict Davenport para niños

In Spanish: Charles Benedict Davenport para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |