Charles I's journey from Oxford to the Scottish army camp near Newark facts for kids

In 1646, Charles I of England was in a tough spot. His side, the Royalists, were losing the First English Civil War. Their main city, Oxford, was about to be surrounded by the Parliamentarian army, called the New Model Army. Charles knew he had to leave Oxford quickly, or he would be captured. He had been talking to different groups fighting against him, trying to find a way to end the war.

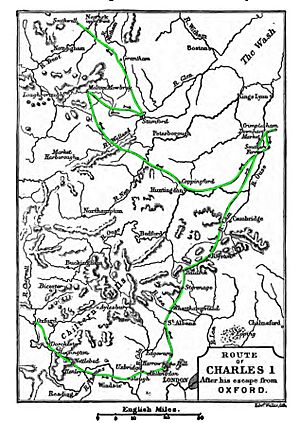

He thought the Scottish army, who were Presbyterians, offered him the best deal. So, on April 27, 1646, Charles left Oxford in secret. He traveled a long, winding path through areas controlled by his enemies. His goal was to reach the Scottish army camp near Newark-on-Trent in Southwell, Nottinghamshire. He finally arrived on May 5, 1646, but things didn't go quite as he hoped. He was put under close guard in a place called Kelham House.

Contents

Why Charles Left Oxford

As the English Civil War was ending, King Charles I kept trying to make deals with his enemies. He hoped to divide them and win politically what he was losing on the battlefield.

When it became clear the Royalists would lose, the Scots, who were allied with the English Parliament, looked for help from Cardinal Mazarin, a powerful French minister. Mazarin sent a diplomat named Jean de Montreuil to Scotland to act as a go-between. Montreuil was supposed to help Charles I keep his throne, but on terms the Scots would like.

Montreuil arrived in London in August 1645. He started talking with English Presbyterians who were friendly with the Scots. The Scots and English Presbyterians had an agreement called the Solemn League and Covenant. This agreement was not popular with all Parliamentarians, especially those called Independents, like Oliver Cromwell.

During these talks, an idea came up: if King Charles put himself under the protection of the Scottish army, the Presbyterian group could gain more power. Montreuil tried to get the Scots to offer Charles the best possible terms. They wanted Charles to agree to three main things: changes to the Church, control of the army, and rules for Ireland. They also wanted him to sign the Covenant, a religious and political agreement. If Charles agreed, they would help him with the English Parliament.

However, Charles was very clever with words. He would often agree to things in a way that he could later say he didn't truly mean. He didn't want to sign anything that was a clear, unbreakable promise.

On March 17, Montreuil went to Oxford, where Charles was staying. He brought the Scottish offer. He also told Charles that English Presbyterians would raise a large army to support the Scots if the New Model Army tried to stop the agreement.

Charles often used clever phrases to avoid difficult truths. After hearing bad news about his army losing a battle, he asked the English Parliament if he could return to London. He wanted all his opponents' achievements in the war to be undone. Both the English Parliament and the Scots rejected this. Charles's plan to divide his enemies actually brought them closer together.

On March 27, the Scots told Montreuil they wouldn't accept Charles's terms. But they said, without writing it down, that if Charles came to their army, they would protect his honor and beliefs.

On April 1, Montreuil wrote to Charles, making a promise. He said that if Charles joined the Scottish army, he would be treated as their rightful king. He and his servants would be safe, and the Scots would help him get a good peace deal and regain his rights. Charles, in turn, promised to bring only two companions, his nephews and John Ashburnham. He also said he was willing to learn about the Presbyterian church and try to agree to things that didn't go against his conscience.

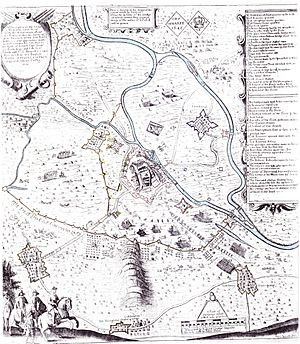

On April 3, Montreuil went to Southwell, Nottinghamshire, near the Scottish army camp. He stayed at the King's Arms Inn. The Scots were besieging the town of Newark. Montreuil was supposed to arrange the final terms for Charles. He believed the Scots were happy about Charles wanting to join them. He even wrote a document, which he thought they approved, promising Charles full protection.

The plan was for Scottish horse soldiers to meet Charles at Market Harborough. But Charles wasn't sure the Scots would keep their word. So, he sent Michael Hudson, a chaplain and scout, in his place.

Hudson went to Harborough but found no troops. He continued to Southwell, where Montreuil told him the Scots were worried about upsetting Parliament. Hudson returned to Oxford with little hope. He only knew the Scots had promised to send soldiers to Burton upon Trent.

More letters arrived from Montreuil. In one, dated April 10, he warned Charles: "They tell me they will do more than can be expressed, but let not his Majesty hope for any more than I send him word of, that he may not be deceived and let him take his measures aright, for certainly the enterprise is full of danger."

Charles felt he had no other choice. His advisor, Ashburnham, said the King was in a very difficult situation, running out of supplies and hope for help. Charles explained his reasons in a letter to the Marquis of Ormond. He said he had sent many messages to Parliament without success. He had also received good promises from the Scots that he and his friends would be safe, and they would help him get peace. So, he decided to risk going to the Scottish army. This letter was dated April 13, 1646. On April 25, Montreuil sent a letter saying the Scottish commanders were now very welcoming. Charles left secretly on April 26, with only John Ashburnham and Michael Hudson, who knew the area well.

The Secret Journey

At midnight on April 27, Charles met the Duke of Richmond in Ashburnham's room. They cut the King's long hair and trimmed his beard so he wouldn't look like the famous portraits by Anthony van Dyck.

Hudson had convinced the King that a direct trip from Oxford to the Scottish camp was too risky. It would be better to take a long, winding route: first towards London, then northeast, and finally northwest towards Newark. To help them travel, Hudson had an old pass for a captain going to London. Hudson wore a red cloak and pretended to be this captain.

At 2:00 am, Hudson got the keys to the city gates from Oxford's governor, Sir Thomas Glemham. At 3:00 am, they crossed the Magdalen Bridge. The governor said goodbye to Charles, calling him "Harry," the name Charles would use as his disguise. Charles was dressed as Ashburnham's servant, wearing a special cap and carrying a bag.

Charles still hoped to hear from people in London who might want to make a deal with him, but no news came. They stopped at an inn in Hillingdon, near Uxbridge, and discussed their next move. They thought about three options: going to London (ruled out due to no news), heading north to the Scots, or finding a ship to leave the country. They decided to head towards King's Lynn in Norfolk. This way, if they couldn't reach Lynn or find a ship, the Scottish option was still open.

They continued their journey, facing many dangers. They passed through fourteen enemy strongholds and had many close calls trying to avoid being seen.

On April 30, Charles and Ashburnham decided to stop at Downham Market in Norfolk. Hudson went ahead to Southwell to finalize the arrangements with the Scots. Hudson later told Parliament what the Scots had verbally agreed to (Montreuil wrote it down in French because the Scots didn't want to put it in writing):

- They would protect the King and his honor.

- They would not force the King to do anything against his beliefs.

- Mr. Ashburnham and Hudson would be protected.

- If Parliament refused to give the King back his rights, the Scots would support the King and protect his friends. If Parliament did agree, the Scots would try to make sure only a few of the King's supporters would be sent away, and none would be killed.

Historian S. R. Gardiner noted that the Scots really wanted to have Charles in their control. However, they probably didn't realize how much Charles disliked the Presbyterian church. Charles had promised to agree to a Presbyterian church, but he could always use the "against my conscience" excuse later. Also, because the terms weren't written down by the Scots, there was room for misunderstanding, especially about when the Scots would provide armed support.

Before setting out again, Charles changed his disguise. Since his first disguise was known, he dressed as a clergyman and was called "Doctor," pretending to be Hudson's tutor.

The small group arrived at Stamford, Lincolnshire on the evening of May 3 and stayed with a local official. Charles and his two companions left between 10:00 pm and midnight on May 4. They traveled all night, going towards Allington and crossing the Trent River at Gotham.

Arriving at the Scottish Camp

Early on May 5, 1646, Charles reached the King's Arms Inn in Southwell, where Montreuil was staying. Charles stayed there through the morning and left after lunch. His arrival caused a stir. Among those who visited him was the Earl of Lothian. Lothian seemed surprised by the "conditions" Charles thought he had agreed to before arriving. He denied them, saying the Scottish leaders in London might have agreed to things they couldn't.

Lothian then gave Charles a list of demands: surrender Newark, sign the Covenant, order Presbyterianism in England and Ireland, and tell his Scottish general, James Graham, Marquess of Montrose, to stop fighting. Charles refused all three. He famously replied, "He that made you an earl, made James Graham a marquess," meaning he had given Montrose his title, just as he had given Lothian his.

After lunch, Charles went to the headquarters of General David Leslie. General Leslie was in charge of the Scottish army besieging Newark. When Charles appeared before General Leslie, the general acted very surprised. It seemed uncertain whether the Scottish army leaders knew about the secret talks between their diplomats and Montreuil.

Whether it was true or not, the Scots insisted that Charles's arrival was completely unexpected. They wrote to the English Parliamentarians, saying the King had come into their army that morning, which "has overtaken us unexpectedly, filled us with amazement, and made us like men that dream." They also wrote to the Committee of Both Kingdoms in London, saying the King came "in so private a way that... we could not find him out in sundry houses. And we believe your lordships will think it was a matter of much astonishment to us, seeing we did not expect he would have come into any place in our power."

One historian, W. D. Hamilton, believed that Charles's refusal to agree to Lord Lothian's demands at Southwell changed his status. He was no longer seen as Montreuil's guest but as their prisoner. After his meeting with General Leslie, Charles was escorted to Kelham House, where he would stay while with the Scottish army.

What Happened Next

At Kelham House, Charles was closely watched by guards, though they called it a "guard of honor." No one could see him or send him letters without permission. Meanwhile, the English and Scottish leaders were talking in the fields between Kelham and Farndon. Montreuil, Ashburnham, and Hudson were still there. Charles, realizing his difficult situation, tried to negotiate with the English Parliamentarians himself.

Ashburnham tried to arrange talks with Lord Belasyse, the governor of Newark, and Francis Pierrepont, a Member of Parliament. But Lord Belasyse told Ashburnham that Pierrepont would not talk to him because Ashburnham had helped the King go to the Scottish army, which made him very unpopular with Parliament. So, Charles's idea of going to the English Parliamentarians didn't work out.

If Ashburnham's talks had succeeded, the whole course of events might have changed. But the Scots held their valuable "prize" securely. Records from the House of Lords show that eight noblemen protested the strict guard the Scottish army kept around the King, not allowing anyone to see him without their permission.

See also

- Escape of Charles II (3 September – 16 October 1651) after the Royalist defeat at the Battle of Worcester

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |