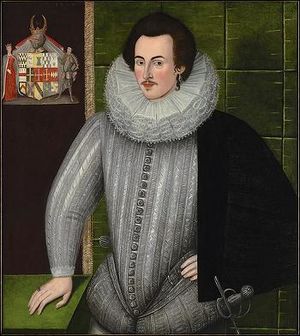

Christopher St Lawrence, 10th Baron Howth facts for kids

Christopher St Lawrence, 10th Baron Howth (around 1568–1619) was an important Anglo-Irish leader and soldier. He lived during the reigns of Elizabeth I (the Elizabethan era) and James I (the Jacobean era) in England.

Christopher was known for his charm, which made him a favorite of both Queen Elizabeth I and King James I. He was also a brave soldier who fought in the Nine Years' War. This was a big rebellion against English rule in Ireland. He served under famous commanders like the Earl of Essex and Lord Mountjoy.

However, Christopher also had a reputation for getting into arguments. He often fought with the Lord Deputy of Ireland (the English ruler of Ireland) and other powerful families in the Pale (the area around Dublin controlled by the English). He was also suspected of being involved in a plot that led to the Flight of the Earls, when many Irish leaders left Ireland.

Today, he is perhaps best remembered for a famous legend. It says that when he was a young boy, he was kidnapped by the "Pirate Queen," Granuaile.

Contents

Early Life

Christopher was born around 1568. His father was Nicholas, 9th Baron Howth. His mother was Margaret Barnewall.

The legend of Granuaile says Christopher grew up at Howth Castle. However, his parents also lived in Platten, County Meath, for some years.

His father was a strong Roman Catholic. This was risky at a time when the English government favored the Protestant faith. Christopher, however, became a Protestant before 1605. Some people thought he did this only to gain power, not because of his true beliefs. Later, he even worked with Catholic nobles and seemed to return to the Catholic faith for a short time.

Granuaile, the Pirate Queen

A famous story, which might be partly true, tells of an event around 1576. Granuaile, also known as the Pirate Queen of Galway, arrived at Howth Castle during dinner. She found the castle gates closed, which was considered very rude.

Annoyed, she took young Christopher hostage. She held him until his family apologized for their lack of hospitality. To make things right, the Howth family promised something important. From then on, the castle gates would always be open at dinner time. Also, an extra place would always be set at the table for any unexpected guests.

A Brave Soldier

Christopher became known as a very skilled soldier. He fought for the English government throughout the Nine Years' War. This war was a major challenge to English rule in Ireland. The rebellion was led by Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone.

In 1595, Christopher joined his father on a trip to Wicklow. He showed his bravery by capturing two men. Later, he spent two years in England and was made a knight. He returned to Ireland in 1597 with Sir Conyers Clifford. He was given command of a cavalry (horse soldiers) company.

He spent a lot of time in Offaly, keeping the O'Connor clan under control. He also became commander of the army base in Cavan. He had the power to enforce martial law, which meant he could make quick decisions about justice. He was praised for his good work there.

Friend of the Earl of Essex

When Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, came to Ireland to stop Hugh O'Neill's rebellion, Christopher served with him. They became good friends.

Christopher showed great courage at Athy. He swam across the River Barrow to get back some stolen horses. He returned with the horses and the heads of two thieves. He was also at the siege of Cahir Castle. There, he bravely pushed back an attack by the castle's defenders. He also went with Essex on his difficult trip to Ulster.

Essex called Christopher a "dear and worthy friend." He chose Christopher as one of the few people to go with him back to England. This was after Essex had made a peace deal with Hugh O'Neill, which was seen as a failure by the Queen.

Christopher was already known for being quick-tempered. In 1598, there was a rumor that he had killed someone over a small insult, but this was not true. He did offer to fight Essex's rivals in the Queen's court. He also caused trouble by publicly wishing Essex well.

He was called before the Privy Council (the Queen's advisors) for threatening a powerful man named Robert Cecil. Christopher denied it and was told to return to Ireland. When someone called him an Irishman as an insult, he replied with dignity. He said he was "an Irishman in England, an Englishman in Ireland." He asked to be judged only on his service to the Queen.

Queen Elizabeth I met with him. She scolded him but was clearly impressed. She allowed him to delay his return and paid him money he was owed. She later wrote that he was "well deserved in her service." He also made peace with Robert Cecil.

Serving Lord Mountjoy

In 1600, Christopher was sent to help Sir George Carew in his military campaign in Connacht. His reputation as a soldier grew, but so did his reputation for violence. He was said to have gotten into a fight with Thomas Butler, 10th Earl of Ormond. The reason was supposedly that Christopher was too friendly with Ormond's wife.

The downfall of his friend Essex did not ruin Christopher's career. When Lord Mountjoy arrived in Ireland to end the Nine Years' War, Christopher joined him. He went on a trip against the O'Mores of Laois. In October 1600, he fought at the Battle of Moyry Pass and was injured.

He was Mountjoy's main helper in central Ireland for several months. However, he later complained that he was not rewarded enough. In August 1601, he was in Ulster. When news came that the Spanish had landed, he was sent to stop Hugh Roe O'Donnell, but he failed. At the Battle of Kinsale, the most important battle of the Nine Years' War, he was given a key job. He had to stop the Irish and Spanish armies from joining forces, and he succeeded.

After this, he was in Dublin and then briefly became governor of Monaghan. When Hugh O'Neill surrendered to Lord Mountjoy, ending the war, Christopher's army was made smaller. He was accused of secretly writing to O'Neill. He wrote to Robert Cecil, asking to go to London to clear his name.

He had also argued fiercely with his officer, Laurence Esmonde, 1st Baron Esmonde. He was accused of illegally hanging an English servant. Because of complaints about his behavior, he was quickly removed as Governor of Monaghan. He was still upset about Essex's downfall. He was also embarrassed by his father's open support for Catholics, who wanted to end the Penal Laws (laws against Catholics).

Since he got no help from the King, he decided to work abroad. This was made easier because his marriage to Elizabeth Wentworth had recently ended. The new Lord Deputy, Sir Arthur Chichester, tried to help Christopher get a job in Ireland. But nothing happened, so Christopher went to work for Archduke Albert in the Spanish Netherlands. Chichester worried that other young nobles would leave Ireland too. However, Christopher's time abroad was cut short when his father died in May 1607. He returned home from Brussels to find his family's wealth greatly reduced by debt.

The Flight of the Earls

In 1607, many Irish leaders left Ireland in what became known as the Flight of the Earls. Christopher certainly played a part in the events leading up to this, but exactly what he did is still a mystery.

Even before he returned to Ireland, he knew about a secret plan. This plan involved Hugh O'Neill, Rory O'Donnell, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell, and others. On a quick visit to England, he told some of the plan to the Privy Council. They told Chichester to question someone called A.B.

When Chichester learned that A.B. was Christopher himself, he didn't believe him. Chichester already had a very low opinion of Christopher. But then, when Tyrone and Tyrconnell actually fled, it proved that at least part of Christopher's story was true.

Since he was clearly involved in the plot, he was arrested and questioned more. Chichester called his answers "half-witted." Christopher's cousin, George St Lawrence, was ready to say that Christopher had been a main leader in the plot. George was sentenced to death for his own part in the plan, but later received a royal pardon (forgiveness from the King). This made Christopher, understandably, fear for his own life.

He was briefly jailed in Dublin and then sent to London. Christopher, despite his faults, had a lot of charm and spoke well. He convinced the Privy Council that he was innocent. He also won the favor of King James I, though his requests for a regular payment were turned down. He returned to Ireland in March 1608.

Christopher's warnings about the plot helped cause the 1608 O'Doherty's Rebellion. This created a sense of fear about a big plot among the Gaelic lords of Ulster. In this tense situation, a simple wood-cutting trip by Sir Cahir O'Doherty was mistaken for the start of a wider plot. O'Doherty felt unfairly treated after this. This led him to rebel, and he burned Derry to the ground.

Many Arguments

Back in Ireland, Christopher found his reputation ruined. He sadly wrote to the King that the King's favor only made his neighbors dislike him more. Most people viewed him with deep suspicion. He claimed to fear for his life and said he couldn't even trust his few remaining friends.

Unwisely, he started arguments with several other important people in the Pale. Sir Garret Moore, 1st Viscount Moore, was related to Christopher by marriage and had been his friend. But Moore now turned against him, calling him a coward and a liar. The exact reason for their quarrel is unclear.

Christopher, in turn, accused Moore of secretly plotting treason with Hugh O'Neill. He also strangely accused Moore of trying to raise the Devil. Although Moore had been friendly with O'Neill, Christopher could not prove the treason charge. The charge of necromancy (trying to raise the dead or spirits) was simply laughed at. Chichester said no one would believe such evidence. The case was moved to England, and Moore was found innocent.

However, Christopher was allowed to go to England. Again, his personal charm won him the goodwill of King James I. The King's fondness for attractive young men was often talked about.

The argument between Christopher and Moore soon included Moore's relatives. These were Thomas Jones, the Archbishop of Dublin, and the Archbishop's son Lord Ranelagh. Lord Ranelagh called Christopher "a brave man among cowards." This led to a violent fight in a tennis court in Dublin in May 1609. A man named Mr. Barnewall was killed.

Christopher claimed that Barnewall, who was his cousin, was killed while defending him. Ranelagh claimed the dead man had tried to stop the fight and was killed by Christopher's men. Chichester, who was nearby, heard about the fight. He sided with Jones and had Christopher arrested right away.

The investigation found that Barnewall's death was manslaughter (killing someone without planning it). Christopher, when questioned by the Irish Council, claimed he was the victim of a plot to murder him. He said Chichester, Moore, and the Jones family were part of it.

The Council found that Christopher had no proof for his claims. They said he was acting out of meanness towards his fellow nobles. The Council ordered him to stay home and improve his behavior. They said the King "much disliked his proud carriage towards the supreme officials of the Kingdom." He was strictly forbidden to go to London, but he went anyway. After a short time in the Fleet Prison, he met the King. Once again, he gained the King's favor. Chichester was told off for being unfair in the Howth-Moore argument. After that, Chichester at least pretended to be friendly with Christopher.

Later Years and Death

Christopher's later years were mostly peaceful, though he had growing money problems. He served in the Irish Parliament from 1613 to 1615. He tried to work with the Catholic opposition, but the King's government didn't take it seriously.

His relationship with Archbishop Jones improved. In 1614, they worked together to raise money for the King in Dublin. Christopher set a good example by giving £100. He arranged for his oldest son to marry into the powerful Montgomery family. He hoped to benefit from the Plantation of Ulster (settlement of Protestants in Ulster) and also to solve his money problems, as his new daughter-in-law was very wealthy.

Christopher died on October 24, 1619. For some reason, he was not buried until late January 1620.

Family

His married life was not happy. He was married to Elizabeth Wentworth. She was the daughter of Sir John Wentworth of Little Horkesley and Gosfield Hall, Essex. Unlike his grandfather, the 8th Baron, Christopher was never accused of treating his wife badly.

Their marriage may have been for love, but it also helped Christopher. The Wentworths owned a lot of land in Essex. Elizabeth's brother, John, married a granddaughter of a duke and left his son a "splendid inheritance." Perhaps the marriage broke down because Christopher and Elizabeth were too similar. Elizabeth was also known for being quarrelsome. In her will, she mentioned a long argument with her older son, whom she now forgave.

The couple married around 1595 but had separated by 1605. The Privy Council ordered Christopher to pay his wife £100 as alimony (money paid to a former spouse). This amount was later lowered, but it was still a heavy financial burden for him. This caused more arguments between them. In 1614, he tried to stop paying altogether, but he failed.

They had three children:

- Nicholas St Lawrence, 11th Baron Howth

- Thomas, who lived in Suffolk and married Elinor Lynne

- Margaret, who married William FitzWilliam first, and then Michael Berford.

His widow, Elizabeth, later married Sir Robert Newcomen. She died in 1627.

Character

People who knew Christopher St Lawrence best, like Chichester and Moore, often judged him harshly. They called him foolish, dishonest, quarrelsome, violent, and irresponsible. He clearly did not have the political skills of his father, who was respected by both his peers and the King. Some might say he inherited a tendency for mental instability from his grandfather.

However, Christopher's courage and military skill were never seriously questioned. A man who became friends with Queen Elizabeth I, King James I, Robert Cecil, the Earl of Essex, and Lord Mountjoy must have had some good qualities.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |