Chronobiology facts for kids

Chronobiology is the study of how living things keep track of time. It looks at the natural cycles, or rhythms, that happen in plants, animals, and even tiny microbes. These cycles help organisms adapt to the daily changes of the sun and the monthly changes of the moon. The word "chronobiology" comes from Greek words meaning "time" and "the study of life."

This field explores how these biological rhythms affect everything from how our bodies work (like sleeping and eating) to our genetics and even our behavior.

Contents

What Chronobiology Studies

Chronobiology looks at how the timing and length of biological activities change in living things. These changes are important for many basic life processes.

- In animals, these rhythms control things like eating, sleeping, mating, and even hibernation or migration.

- In plants, they affect leaf movements and how they make food using sunlight (photosynthesis).

- Even tiny organisms like bacteria have these rhythms!

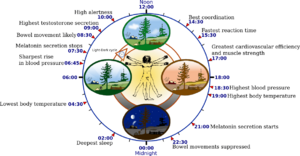

The most famous rhythm studied in chronobiology is the circadian rhythm. This is a cycle that lasts about 24 hours. It controls many body processes in almost all living things. The word "circadian" means "around a day" in Latin. Our bodies have special "circadian clocks" that manage this rhythm.

Within the 24-hour circadian rhythm, we see different patterns:

- Diurnal animals are active during the day.

- Nocturnal animals are active at night.

- Crepuscular animals are most active around dawn and dusk, like some deer or bats.

While circadian rhythms are controlled by internal body processes, other cycles can be affected by outside signals. For example, a plant's internal clock might control how active certain bacteria are by changing how much food the plant provides.

Many other important cycles are also studied:

- Infradian rhythms are cycles longer than a day. Examples include yearly cycles that control animal migration or plant reproduction. The human menstrual cycle is also an infradian rhythm.

- Ultradian rhythms are cycles shorter than 24 hours. An example is the 90-minute REM cycle during sleep.

- Tidal rhythms are seen in ocean animals. They follow the roughly 12.4-hour cycle of high and low tides.

- Lunar rhythms follow the lunar month (about 29.5 days). These are important for sea life because the tides change with the moon's phases.

- Gene oscillations mean that some genes are more active at certain times of the day than others.

During each cycle, the time when a process is most active is called the acrophase. When it's least active, it's in its bathyphase or trough phase. The exact moment of highest activity is the peak, and the lowest point is the nadir.

History of Chronobiology

People first noticed biological cycles in the 1700s. A French scientist named Jean-Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan saw that plant leaves moved in a daily rhythm, even without sunlight. Later, in 1751, the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus designed a "flower clock." He used different types of flowers that opened at specific times of the day. By arranging them in a circle, he could tell the time just by looking at which flowers were open! For example, a certain type of hawk's beard flower opened at 6:30 am, while another kind didn't open until 7 am.

The field of chronobiology really started to grow after a big meeting in 1960 at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. In the same year, Patricia DeCoursey created the "phase response curve," which is a key tool still used in this field today.

Franz Halberg from the University of Minnesota is often called the "father of American chronobiology." He even came up with the word "circadian." However, Colin Pittendrigh became the leader of the Society for Research in Biological Rhythms in the 1970s. Halberg was more interested in human health, while Pittendrigh focused on how rhythms evolved and how they affect different organisms.

How Light Affects Our Internal Clock

Our eyes do more than just help us see images. They also play a big role in setting our internal biological clock.

Special Cells in Your Eyes

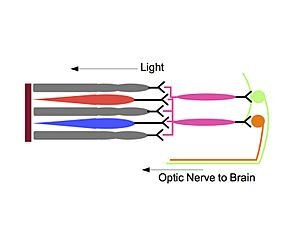

In 2002, a scientist named Samer Hattar and his team found that special cells in the eye, called ipRGCs, are very important for this. These cells contain a light-sensitive chemical called melanopsin. Unlike the rods and cones that help us see, ipRGCs don't help us form images. Instead, they sense light levels and send signals to our brain's internal clock.

These ipRGCs send messages along the optic nerve to a part of the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). The SCN is like the main control center for our body's daily rhythms. Hattar's research showed that melanopsin is the key chemical that allows these ipRGCs to sense light and help set our biological clock.

Different Kinds of ipRGCs

Scientists have since learned that there isn't just one type of ipRGC. There are at least five different types (M1 through M5), and they each have slightly different jobs. Some of these cells send signals to the SCN to control our sleep-wake cycle, while others might control things like how our pupils react to light. This shows how complex and specific our body's light-sensing system is.

Light, Mood, and Learning

Studies have shown that getting light at unusual times can mess up our internal clock. This can lead to not getting enough sleep and can affect our mood and how well we think.

How Light Affects Mood

The ipRGCs in our eyes send signals to parts of the brain that control our mood and emotions. Hattar's lab did a study in 2012 with mice. They exposed some mice to a strange light cycle (3.5 hours of light, 3.5 hours of dark) instead of a normal 12-hour light/dark cycle.

Even though these mice got the same total amount of sleep, they showed signs of depression. They were less interested in sweet water and showed more "despair" in a swimming test. Their stress hormone levels were also higher, which is often linked to depression. This suggests that unusual light patterns can directly affect mood, even if sleep isn't completely disrupted.

How Light Affects Learning

The hippocampus is a part of the brain important for memory and learning. It also receives signals from the ipRGCs. The mice in the strange light cycle also had trouble learning. They struggled with a maze task that tested their spatial memory. This means that unusual light exposure can also make it harder to learn and remember things.

Interestingly, mice that didn't have these special ipRGCs were not affected by the strange light cycles. This shows that the light information sent through these cells is very important for controlling our mood and how well we learn.

New Discoveries in Chronobiology

Scientists are always learning more about chronobiology.

- Light and Melatonin: Researchers like Alfred J. Lewy and Josephine Arendt are studying how light therapy and the hormone melatonin can help reset our body clocks. They've found that even dim light at night can help animals adjust their rhythms faster.

- Chronotypes: People have different "chronotypes." This means some people are naturally "morning people" (early birds) and others are "evening people" (night owls).

- Meal Times: There's also an internal clock that's affected by when we eat. This "food clock" helps control our activity levels, especially when we need to find food.

- Internet Patterns: Studies have even shown that people's online behavior, like what they post on social media, follows daily patterns. These patterns weren't even changed much by the 2020 UK lockdown!

- Rhythm Modulators: In 2021, scientists created new substances that can change the rhythms of body tissues for days. These might help in future research or even to fix organs that are "out of sync."

Other Fields Chronobiology Works With

Chronobiology is a field that connects with many other areas of study. It works closely with:

- sleep medicine (how we sleep)

- endocrinology (hormones)

- geriatrics (aging)

- sports medicine (athletes' performance)

- space medicine (how space travel affects the body)

- photoperiodism (how light affects plant and animal growth)

See also

- Bacterial circadian rhythms

- Biological clock (aging)

- Circadian rhythm

- Circannual cycle

- Circaseptan, 7-day biological cycle

- Familial sleep traits

- Frank A. Brown, Jr.

- Hitoshi Okamura

- Light effects on circadian rhythm

- Photoperiodism

- Suprachiasmatic nucleus

- Scotobiology

- Time perception

In Spanish: Cronobiología para niños

In Spanish: Cronobiología para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |