Jean-Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jean-Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan

|

|

|---|---|

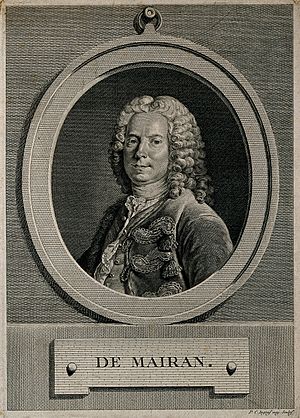

Engraving by Pierre-Charles Ingouf (1746–1800)

|

|

| Born | 26 November 1678 |

| Died | 20 February 1771 (aged 92) Paris

|

| Education | University of Toulouse |

| Known for | Studies of circadian rhythm |

| Awards | Elected to the French Academy of Sciences, Fellow of the Royal Society, Foreign Member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Geophysics, astronomy, chronobiology |

| Patrons | Cardinal de Fleury, Louis XV, Prince of Conti, Duke of Orléans |

| Doctoral advisor | Nicolas Malebranche |

| Influenced | Augustin Pyramus de Candolle |

Jean-Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan (born 26 November 1678 – died 20 February 1771) was a French scientist. He was born in Béziers, France. De Mairan lost his father when he was four and his mother when he was sixteen.

During his life, de Mairan joined many important science groups. He made important discoveries in different areas, including old writings and astronomy (the study of space). His work also helped start the study of circadian rhythms. These are the natural daily cycles in living things. De Mairan passed away in Paris at the age of 92 from pneumonia.

Contents

About Jean-Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan

De Mairan went to college in Toulouse from 1694 to 1697. He focused on learning ancient Greek. In 1698, he moved to Paris to study mathematics and physics. He learned from a teacher named Nicolas Malebranche.

In 1702, he returned to his hometown of Béziers. There, he began to study many different fields. His main interests were astronomy and the daily rhythms of plants. He often ate with the local Bishop, Louis-Charles des Alris de Rousset. In 1723, de Mairan became a member of the Académie Royale des Sciences. He also helped start the Académie de Béziers. This academy was supported by Cardinal de Fleury. Fleury was a powerful minister to King Louis XV.

Later, de Mairan lived in the Louvre palace. He worked as a full-time member of the Académie until 1743. He was also a secretary for the Académie from 1741 to 1743. In 1746, he became a full-time surveyor. Important people like the Prince of Conti gave him many gifts. He also worked as a secretary for the Duke of Orléans.

De Mairan's Scientific Discoveries

De Mairan made several important observations and experiments:

- In 1719, de Mairan talked about how the angle of sunlight changes. This causes cold in winter and heat in summer. He thought the sun's heating power was linked to its height in the sky. He did not consider how the atmosphere might block the sun's heat. Later, he wrote a paper about how much sunlight the atmosphere blocks. His work, even if not fully correct, inspired his student, Pierre Bouguer. Bouguer then invented the photometer, a tool to measure light.

- In 1729, de Mairan did an experiment that showed plants have a circadian rhythm. This is like an internal clock. (You can read more about this below.)

- In 1731, he saw a cloudy area around a star near the Orion nebula. This cloudy area is now known as M43. Charles Messier later named it.

- In 1731, he published a book about the Northern Lights. He suggested that the Sun caused them. He thought it was from the atmosphere mixing with zodiacal light. At that time, people thought the Northern Lights were 'flames' from gases coming out of the Earth.

De Mairan's Plant Rhythm Experiment

In 1729, de Mairan did an important experiment. It showed that plants have daily rhythms, even without sunlight. He used a plant called the Mimosa pudica. This plant is also known as the "sensitive plant."

He noticed that the leaves of the Mimosa pudica opened during the day and closed at night. He wanted to see if this happened because of sunlight or something else. So, he put the plants in a dark room. He watched what happened to their leaves.

De Mairan found that the leaves still opened and closed at the same times each day. This happened even though they were in constant darkness. He concluded that the plants could "sense the Sun without ever seeing it." He didn't realize that plants had an "internal clock." This idea came much later. But he did wonder if heat could make plants act as if it were day or night.

His friend, Marchant, published de Mairan's work. This helped his findings become known. It was common for scientists to share each other's work back then. De Mairan's one-page paper is still important today. Colin Pittendrigh, who started modern chronobiology (the study of biological rhythms), recognized de Mairan's work.

You can see a video of a cucumber plant's daily rhythms in constant darkness . It's similar to what de Mairan observed.

De Mairan's Lasting Impact on Science

For a long time, people thought plant movements were only controlled by outside things. They thought light, dark, temperature, or even a mystery "X-factor" caused them. This was despite de Mairan's work, which suggested plants had internal clocks.

Almost 100 years after de Mairan, in 1823, a Swiss botanist named Augustin Pyramus de Candolle continued this work. He measured the daily leaf movements of the Mimosa pudica in constant conditions. He found their cycle was about 22–23 hours long. This was the first hint of what we now call a circadian rhythm. "Circadian" comes from Latin words meaning "about a day." These rhythms are found in almost all living things, even some bacteria.

Scientific Groups and Awards

In 1718, de Mairan joined the Académie Royale des Sciences. In 1740, important leaders chose him to replace Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle as the "Secrétaire perpétuel" (permanent secretary) of the Académie. He only accepted this job for three years and left in 1743. De Mairan also served as the Académie's assistant director and director many times between 1721 and 1760.

He was also chosen to be the editor of the Journal des sçavans. This was a science magazine. In 1735, de Mairan became a Fellow of the Royal Society in London. In 1769, he became a Foreign Member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. He was also a member of the Russian Academy (St. Petersburg) in 1718. De Mairan was part of many other important science groups. He even started his own science group in Béziers around 1723 with Jean Bouillet and Antoine Portalon.

Selected Publications

Besides his work on astronomy and plant rhythms, de Mairan also studied other areas of physics. These included "heat, light, sound, motion, the shape of the Earth, and the aurora (Northern Lights)."

Here is a short list of some of his published works:

- Dissertation sur les variations du barometre (Bordeaux, 1715) (Essays on how barometers change)

- Dissertation sur la glace (Bordeaux, 1716) (Essay on ice)

- Dissertation sur la cause de la lumiere des phosphores et des noctiluques (Bordeaux, 1717) (Paper on why glowing things and nightly lights shine)

- Dissertation sur l'estimation et la mesure des forces motrices des corps (1728) (Essay on measuring the forces that move objects)

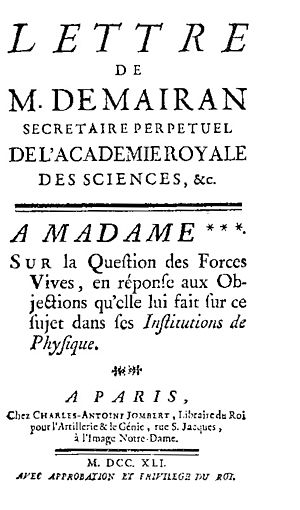

- Lettre de m. de Mairan a Madame. Sur la question des forces vives (1741) (Letter to Madame Chatelet on the Question of Living Forces). This was part of a public discussion with Émilie du Châtelet about forces vives (living forces).

- Traité physique et historique de l'aurore boréale, (1733) (Physical and historical book about the Northern Lights)

See also

In Spanish: Jean-Jacques Dortous de Mairan para niños

In Spanish: Jean-Jacques Dortous de Mairan para niños