Civilian life under the German occupation of the Channel Islands facts for kids

Life for people in the Channel Islands became very hard during the five years they were occupied by Nazi Germany. This period lasted from June 30, 1940, to May 9, 1945. Islanders had to follow German laws to survive. They also had to work with the German soldiers to make life a little easier. The British government did not tell them how to act. So, some people became friendly with the Germans. Others tried to resist them.

Most islanders felt they had no choice but to accept the changes. They hoped that outside forces would eventually free them. The winter of 1944-45 was especially tough. Food and fuel were very scarce. But between big events, daily life continued as best as it could. There were many German soldiers and workers on the small islands. Yet, most civilians tried to keep their distance from them.

Contents

- Key Moments of the Occupation

- Leaving the Islands

- Life Under German Rule

- Homes and Property

- Work and Jobs

- Food and Rations

- Clothing and Commerce

- Education and Fun

- Transport and Fuel

- Communication

- Health and Resistance

- Collaboration and Friendships

- Help for Civilians

- Liberation and Aftermath

- Images for kids

- See also

Key Moments of the Occupation

Many important events affected everyone living in the Channel Islands:

- June 1940: Children and adults left for the UK.

- June 28, 1940: German planes bombed the islands.

- July 1940: German troops arrived, and the occupation began.

- Winter 1941-42: Many more soldiers and builders came to the islands.

- September 1942 and February 1943: Some civilians were sent away to Germany.

- October 1943: A large funeral was held for British sailors. This happened mostly in Guernsey.

- June 6, 1944: The Normandy landings (D-Day) happened in France.

- December 27, 1944: The ship SS Vega brought Red Cross food parcels.

- May 9, 1945: The islands were finally freed.

Leaving the Islands

Before the war, some islanders had already left to join the armed forces. In May 1940, more people started to leave. They feared a German invasion. The UK and island governments arranged ships for evacuation. Many school children from Guernsey left quickly. Teachers were told to go with them. Parents usually could not travel unless they had a very young child. In Jersey, schools were not ordered to evacuate.

Later, more people could leave. But there were not enough ships. To avoid panic, people were told to "stay put." This caused a lot of confusion. Almost everyone left Alderney. Very few left Sark. About 6,600 left Jersey, and 17,000 left Guernsey. Some ships even sailed from Jersey empty.

Deciding to leave or stay was a personal choice. Some left to fight in the war. Others were simply scared. People stayed for many reasons. Some were defiant and did not want to be scared away. Others were too old to move. Some did not want to abandon their businesses or homes. Many stayed to care for elderly parents or pets. Essential workers were asked to stay for their duty. Some people simply missed the last boats. King George VI sent a message of hope to the island leaders. He asked them to read it to the people.

Over 25,000 people, mostly children, went to Britain. But 41,101 stayed in Jersey. 24,429 stayed in Guernsey, and 470 in Sark. Only 18 people remained in Alderney. The island governments in Jersey and Guernsey continued to operate. But emergency services had fewer staff because of the evacuations.

The British government decided on June 15 to remove all military from the islands. All soldiers, weapons, and equipment went to England. They did not tell the Germans this. On June 28, German bombers attacked the islands. They bombed and shot at places like the harbours of Saint Peter Port and Saint Helier. This killed 44 civilians and injured over 70. A ship in Guernsey harbour tried to fight back, but it was not effective.

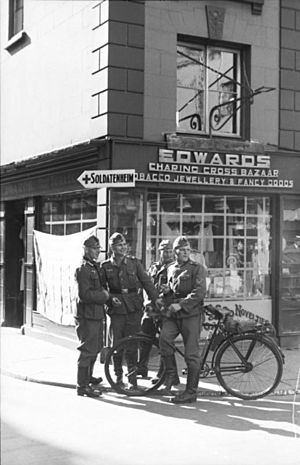

German commanders were planning to invade the islands. But on June 30, a German pilot landed at Guernsey airport. He saw that the island was not defended. He told his leaders. More planes were sent. A German plane landed, and the police chief confirmed the islands were undefended. The next day, German troops arrived by plane on both islands. The occupation had begun. Everyone who stayed was trapped for almost five years.

Rules Under Occupation

Britain had occupied lands far away before. But there was little advice on how citizens should act under enemy occupation. The island governments were told by Britain to stay. Their job was to keep law and order. They also had to help the civilians. The King's representatives left on June 21, 1940. Their powers went to the island leaders, called bailiffs. This meant the bailiffs had to protect the islands and their people.

Changes in Government

In Guernsey, the government decided on June 21, 1940, to let a special committee run things. This committee had almost all the power. Its president was Ambrose Sherwill. He was chosen because he was younger and stronger than the bailiff. Sherwill was later jailed by the Germans. This was because he tried to hide British soldiers. He was released but banned from office in January 1941. Another leader, Jurat John Leale, took his place.

In Jersey, the government also created new departments. These were led by elected members. The leaders of these departments and other officials formed a council. The bailiff led this council. These smaller groups could meet in private. This allowed them to discuss how much to follow German orders.

Life Under German Rule

The island governments made emergency laws to handle the crisis. When the Germans arrived, they had to make agreements. This was to lessen the impact of the occupation on civilians. Businesses had to follow new rules. Individuals generally tried to avoid contact with the Germans.

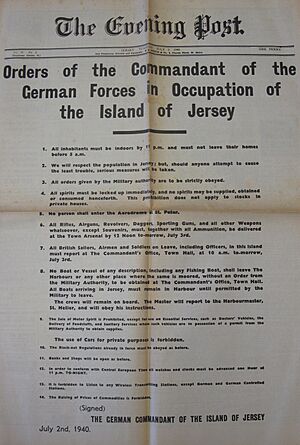

The Germans issued new laws when they arrived. As time went on, more laws restricted people's rights. These laws had to be obeyed.

If someone was caught and sent to prison, it was very hard. Food rations were about half of what civilians got. If sent to prison away from the islands, it was even worse. The risk of dying increased. Later in the war, prisoners caught with radios were released early. This was to save German food supplies.

Church services were allowed. Prayers for the British royal family were permitted. But nothing could be said against the German government. German soldiers could attend services. Outdoor meetings were banned. Some groups like the Salvation Army were also banned.

Some people resisted, but with little success. One notable event was hiding some German workers. This led to several civilians being jailed. One woman, Louisa Gould, died in a concentration camp.

German Rules

The German military command, called Feldkommandantur 515 (FK515), handled civilian matters. They worked with the island authorities. The number of German troops varied. In October 1944, there were about 25,000 soldiers. An extra 15,000 workers from the Organisation Todt (OT) arrived in October 1941. These workers built fortifications.

German soldiers were told to be polite to islanders. At first, they were. There were no rules against them being friendly. Soldiers were punished for crimes against civilians. But as the war went on, the quality of soldiers changed. Their manners and attitudes got worse. Serious problems arose in the last year of the occupation. Food was very scarce then.

The local German commanders seemed to try to keep civilians happy. They let islanders govern themselves. They paid for work done. They did not enforce too many harsh orders from France. But resistance by islanders was not tolerated. Punishing those found guilty was meant to stop others.

The Germans used propaganda. They promoted outdoor band concerts. One person sent to Germany in 1942, Denis Cleary, was returned. He gave glowing reports of warm huts and plenty of food. This was to make the occupation seem better.

Discipline Among Soldiers

German soldiers usually obeyed their superiors. Discipline was generally good. But as new, less disciplined soldiers arrived, it got worse. Most soldiers knew they had a safe place to be. They did not want to risk being sent to the war front.

Soldiers soon learned that islanders were loyal to the British King and Queen. They just wanted the Germans to leave. Most soldiers kept their distance from islanders. But some became friendly. A few soldiers even returned after the war to marry islanders. Soldiers who went home on leave brought back stories of bombed cities. This lowered morale.

Off-duty, soldiers had many ways to pass the time. They had local newspapers, cinemas, and churches. Live shows and sports were encouraged. They had clubs and hobbies like photography. And, of course, there were the beaches. The islands were even promoted as a tourist spot for German soldiers.

Island Governments

The island authorities could keep managing civilians, courts, and services. There was limited interference. But all new laws needed German approval. Any German laws affecting the people had to be registered like local laws. Breaking these laws would usually be tried in island courts, not German military ones. Losing this right would mean direct German rule. The Germans threatened this many times. Under this agreement, unacceptable German laws, like those about Jewish people, were also registered.

The island governments used special committees to run things. This was seen as a subtle form of passive resistance. Working with the Germans had benefits. They could get wood for civilians. Rations stayed higher. They could use German ships to bring food and clothing from France. Police officers sometimes ignored small rule breaks. They even arrested Germans for crimes.

The islands had to pay for the German troops stationed there. This included wages, rent, food, and transport. The islands objected to paying for too many troops. Some amounts charged from 1942 were never paid. But income tax rose sharply. New taxes were added. Civil servant pay was cut. Even so, the islands ended the war with a debt of £9 million. This was about the total value of every house on the islands.

Both the Germans and island authorities wanted to stop the black market. Hoarding food and selling things secretly were crimes. These were often linked to thefts. The island police and German military police dealt with them. Interrogations could be harsh.

Money from the Germans was used to buy food and other goods from France. This continued until mid-1944.

Unpopular German laws were sometimes argued against. Laws about registering Jewish people caused controversy after the war. The island authorities could not win many of these battles. But Jersey did refuse to let patients from their mental hospital be sent to France.

The civil authorities often had to collect information. They did not always know what it was for. In 1941, they took a census of all civilians. This list was later used to identify people for deportation to camps in Germany in 1942 and 1943.

Civilians' Daily Lives

Before the Germans arrived, the island governments were the biggest employers. By Christmas 1940, 2,400 men in Jersey were unemployed. Many businesses closed or had fewer staff. So, many jobs disappeared. The island governments tried to create relief work. They paid less to single men or men whose families were in England. They also cut civil servants' salaries in half.

Civilian buses stopped running in July 1940. Drivers still worked for the bus company. But they had to transport German soldiers instead. The same happened in hotels taken over by Germans.

The Germans needed builders, electricians, plumbers, and many other workers. They offered twice the normal island pay. All young men had to register with the German command. They could be "recruited" if they were not doing useful work. By 1943, about 4,000 islanders worked directly for the Germans. Most skilled workers for the German building projects were volunteers. They were paid and fed better than forced laborers from other countries. The Germans would demand labor. One job involved 180 men helping to level the airport. This was against the Geneva Conventions. Other jobs, like harvesting in Alderney, were less problematic.

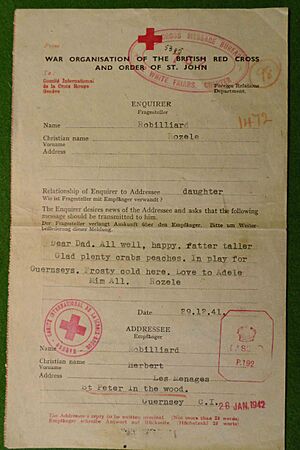

Everyone had to carry ID cards. There were many rules. People could not sing patriotic songs. They had to cycle on the right side of the road. There were curfews and fishing limits. Food was rationed. Houses were taken over (2,750 in Guernsey). The Germans took lorries, cars, and bicycles. The island government had to pay for them. Radios and certain books were also taken. Necessary items ran out as the war went on. German soldiers and OT workers lived in 17,000 private houses in 1942. Children had to learn German in school. Islanders could only communicate with their families in Britain through infrequent Red Cross messages.

Churches and chapels faced challenges. German ministers held military services in borrowed churches. A German flag was placed over the altar. But civilian services were open to everyone. Islanders, Germans, and OT workers, including Russians, prayed and sang together. German police sometimes attended services to ensure sermons followed the rules.

The treatment of people sent away from the islands was better than in other parts of Europe. The Germans cooked food for them at Guernsey harbour. They put them on clean ships. They traveled in second-class train carriages, not animal carts. They also got food for the journey.

The Germans installed 100,000 mines. Several islanders died from them. But a lack of important medicines, like insulin, caused more civilian deaths.

Survival became harder with less food and no fuel. Death rates rose. Those with money could buy extra food on the black market. Islanders were saved from starvation by the ship SS Vega. It brought Red Cross parcels during the winter of 1944–1945.

No civilians were sent to Germany to work in factories. This happened in most other occupied countries. Local people working for the OT were paid. They worked voluntarily and only in the islands. The OT paid them 60% more than normal civilian wages. German behavior towards civilians was generally better than in other occupied areas.

Alderney and Sark

Almost no civilians lived in Alderney during the occupation. The few who stayed worked to feed themselves. They also worked for the thousands of OT workers and soldiers. A few islanders were asked to do temporary work in Alderney, like marine diving.

On Sark, the occupation was mostly peaceful. There were two British commando raids. An Avro Lancaster bomber also crash-landed there. Some Sark citizens were deported. But the soldiers were very well-behaved. The island traded fish with Guernsey for other goods.

Different Groups of People

People on the islands fell into different groups. Each group had people they did not trust, disliked, or saw as enemies:

- German army soldiers came from many countries. This included Germany, Austria, and Poland.

- Soldiers from eastern countries were called Ostlegionen soldiers. They were treated worse and were often hungry. They feared being sent back to Russia.

- Organisation Todt (OT) workers had three types:

- Volunteer experts: They came from many countries. They were well paid and had benefits.

- Semi-volunteer workers: They often had little choice but to volunteer. They were paid and had some time off.

- Unskilled forced workers: They were paid little and treated badly. They were like slave workers. Most were in Alderney camps.

- Local islanders also had many categories. There were "informers," "black marketeers," and those "too friendly with the enemy." Some "worked for the Germans." Others "antagonized the Germans." Most were just "normal" civilians.

Locals could be OT workers. German soldiers and OT workers could also be black marketeers. Anyone could be a criminal. People had different religious beliefs and political ideas. A few people lived "underground," hidden from sight. These might be Jewish people, escaped OT workers, or escaped prisoners. Authority was enforced by the German military police and the local police.

Homes and Property

At first, German troops stayed in empty hotels. But within months, their numbers grew. Empty buildings, like schools and houses of evacuated people, were taken over.

In late 1941, Hitler decided to fortify the islands. Tens of thousands of soldiers and 15,000 construction workers arrived. They all needed places to live. Some huts were built for OT workers. But many soldiers and workers stayed in private houses that had a spare room. By 1942, 17,000 private houses had German soldiers or OT workers living in them. Households with a soldier living there were paid a small amount each week. But they had to do his laundry.

Furniture was taken or simply removed. After the war, people had to search through large stores of furniture to find their belongings. Jersey had 185,000 items of furniture needing owners. A few people were ordered out of their homes quickly. This happened if their house was needed for soldiers or for building fortifications. Sometimes, houses were even torn down.

The Germans demolished some buildings. This was often to improve views for guns or to remove landmarks. In Guernsey, they destroyed the Cobo Inn, the Cobo Institute, and two monuments.

Work and Jobs

The occupation affected most workers, especially those in shops and offices. Many people had left, creating job openings. But many businesses saw a huge drop in sales. So, they needed fewer employees. Some jobs, like bus and taxi drivers, disappeared overnight. People in the building trade found that the German army became their main employer.

Unemployed people relied on charity from their parish. So, the island governments started work programs by the end of 1940. This gave jobs to the growing number of unemployed. In Jersey, 2,300 men were unemployed. This system continued throughout the occupation. Work included road improvements, cutting wood for fuel, and getting water mills working again. Jersey set up a factory that employed 250 people. They sorted, made, and repaired clothes and shoes. Guernsey created a boot factory. Even so, the wait for a pair of shoes could be a year.

Workers in essential services, like utilities, had to provide telephone, electricity, and water to German buildings. This included the new fortifications. They also continued their normal work.

Civil servants had their pay cut. The governments also set a weekly wage rate. They also set maximum prices for almost everything. There were complaints that prices were too low. This led to selling things "under the counter."

German pay rates were higher. This attracted workers who could not live on the low civilian wages. The OT offered twice the normal island pay. In Jersey, 600 people were attracted by the higher wages.

In most European countries, Germans forced adults to work in factories and on farms in Germany. This did not happen to islanders.

Food and Rations

The islands used to import 80% of their food. After many civilians left, there were fewer mouths to feed. But the number of German soldiers and OT workers grew. This put a strain on limited food supplies.

At first, local farms provided most of the food. Some food also came from France. Anyone with a garden was encouraged to grow vegetables. Seeds were brought from France when local supplies ran out. Many people raised hens and rabbits. But these were often stolen and had to be guarded.

Women often spent hours queuing for the little food available. They sometimes knitted while waiting. Often, they would reach the front to find nothing left. Then, after collecting sticks and water from a well, they would spend hours preparing a meal. Men and children often ate more than their share.

Civilians on rations got about 1,350 calories per day from 1941-44. The minimum needed is 1,500 for women and 2,000 for men. Rations halved in the winter of 1944-45. Food became an obsession. Poor people in towns queued for hours for a few cabbage leaves and potato peelings. They would faint from hunger, even after Red Cross parcels started to arrive.

Farming and Growing

Guernsey continued to grow tomatoes from 1940 to 1943. Tons were shipped to France on German military ships. In Jersey, potato crops were grown as usual. The food was used for export and local eating. Seed potatoes for Guernsey came from France.

A lack of fertilizer caused productivity to drop. Local seaweed, called Vraic, was hard to gather. Access to beaches was restricted. From 1942-43, Jersey lost access to 1,555 acres of farmland. This was 10% of their total. These areas became part of new fortifications.

Taking Food

The island governments had to pay for the occupation. This meant they had to pay for the soldiers' food. The Germans took food that was grown. It was then shared between civilians and soldiers. The sharing was negotiated. But the Germans had control. So, soldiers got more as the war went on. Even so, soldiers were close to starving in the winter of 1944–45.

Fishing

Fishing was an important industry. Some fishing boats had sailed to England in June 1940. Fishing was banned in September 1940 after an escape. When allowed again, there were restrictions. This included limits on fuel.

Whenever another boat fled the islands, restrictions increased. A German guard boat or soldier was often placed on each boat. The fish catch decreased. But it provided useful calories. Germans took 20% of all catches.

Fish was rationed to about 1 pound a week per household from May 1941.

Gathering shellfish like limpets and winkles from the shore was allowed in certain places at certain times. Rod fishing was also allowed on some beaches. People had to be careful of barbed wire and mines. Limpet pie was tasty. But it needed two hours of boiling before being cooked with vegetables.

Rations and Red Cross Parcels

Rationing was already in place, similar to England. It was changed in August 1940 to fit food available from France. The islands set up a buying group in France. They bought tens of thousands of tons of goods for cash. These goods were shipped to the islands on German ships.

Soon, every type of food, except vegetables and fruit, was rationed. Clothing and footwear were also rationed. Milk was rationed from October 1940 to half a pint per day. The island cows were not killed for meat. Milk, butter, and cheese were more important.

Rations for civilians were cut. By the end of 1944, they were at a starvation level. The amount of rations depended on whether you were German, a civilian, or a heavy manual worker.

A few hundred Red Cross parcels arrived in spring 1943. They came from islanders who had been sent to camps in Germany. These deportees were treated like prisoners of war. They received many parcels. Knowing conditions were bad on the islands, they sent treats to friends and family.

In August 1944, Britain refused a German offer to evacuate civilians from the islands. But in November 1944, the Bailiff of Jersey sent a message to Britain. He told them about the low food supplies. He asked for Red Cross help. Britain agreed. It was very unusual for Red Cross parcels meant for prisoners of war to be given to civilians.

The ship SS Vega arrived at the end of December 1944. It brought Red Cross parcels. This saved many lives. The ship returned four more times before liberation in May 1945. The third trip brought flour. The island had run out in February. This white flour allowed everyone to get a 2-pound loaf of bread.

460,000 food parcels, each weighing over 10 pounds, came from Canada and New Zealand. They were given to the 66,000 civilians. These were the same parcels sent to prisoners of war.

Church collections for the Red Cross in early 1945 raised thousands of pounds. People were so thankful. By October 1945, £171,000 was raised. This is like £6,000,000 today. The Red Cross remained a popular charity after the war.

Clothing and Commerce

Clothing and shoes quickly became scarce as shops sold out. Jersey opened the Summerland factory to make clothes from blankets, curtains, and sheets. Nothing was thrown away. Knitted items were unraveled and remade. Other clothes were patched and repaired. Clothes from evacuated people's houses were taken. As people lost weight, new clothes were needed or old ones adjusted. Elastic ran out. Shortages of needles and thread were helped by supplies from France.

Shoes were a big problem. Leather was impossible to get. Shoe soles were made from rope and wood. Uppers were knitted. 45,000 pairs of wooden shoes, called sabots, were made in Jersey. These stiff shoes caused foot problems. In 1943, the footwear controller in Guernsey supplied 60 people a day with shoes.

Washing clothes became hard over time. There was no soap and no fuel to heat water. Most people outside towns used wells for water.

Businesses and Banks

Most businesses kept operating as long as possible and as long as they had stock. They could not treat local and German customers differently. The Germans had a very good exchange rate. So, they bought everything in large amounts and sent them back to Germany. Many items were resold for profit. Shops did not hold back goods for locals until later in the war. Business hours were cut. Shop workers, who used to work long hours, were reduced to 20 hours a week.

A few businesses decided to work for the Germans. A Guernsey firm took over more and more land and greenhouses. They grew food only for Germans. They also got access to German transport to export food to France.

Banks had their main money in London, which was unreachable. So, they had to freeze customer accounts. The island governments had to promise to repay the banks. This was so the banks would give people money.

People who evacuated could only take a limited amount of cash. They put deeds and valuables in safe deposit boxes. Germans later demanded access to these boxes, looking for valuables.

British money became rare in 1941. It was replaced by local notes. German occupation marks were also used. They had a fixed exchange rate that favored the Germans. At the end of the war, German marks were converted to British money at face value. A British army truck arrived with £1 million in Bank of England notes. This annoyed one farmer who had burned two suitcases full of occupation notes days before, thinking they were worthless.

Shops and Bartering

Shops quickly ran out of supplies. German soldiers bought many luxury items to send home. Locals with money also bought goods while they were available. Shops also hoarded goods, waiting for prices to rise.

Few supplies arrived from France to restock shops. Almost all goods had a government-set maximum price. Vendors were fined heavily for selling above this price.

Bartering became common. People advertised in shops and papers. They offered goods to meet a specific need. For example, a nightgown for flour, or a rabbit for good shoes. Empty shops became places for exchanges for a small fee.

Repair shops were in high demand. Especially bicycle, machinery, and shoe repair shops. Old fire hoses were made into bicycle tires. Garden hoses were also used. Chemists had to create scarce items like glue and matches. Oil and paraffin lamps were made from tins.

Education and Fun

Schools

5,000 Guernsey schoolchildren had been evacuated. Many empty classrooms closed. Some schools were used as barracks or offices by soldiers. One school in Guernsey became a hospital. The Jersey College for Girls building also became a hospital. A few teachers stayed in Guernsey. Retired teachers helped teach the 1,421 children who remained.

In Jersey, most children stayed. All but 1,000 of 5,500 children remained. They had 140 teachers. All schools had air raid shelters. Exams for 11-year-olds continued as normal. The only change was compulsory German language teaching from January 1942. Local teachers taught it to avoid German officers in schools. Paper was scarce, so slates were used again.

The school leaving age in Jersey was raised to 15. This was to keep youngsters out of trouble. But two girls, aged 14 and 15, spent three days in jail for spitting cherry stones at Germans. Classrooms were unheated, and lighting was limited. Even so, older students took exams. After the war, leaving certificates were given once papers were marked.

Entertainment

The occupation had some impact on entertainment. Germans provided band concerts in parks. Theatres stayed open, sometimes in church halls, until summer 1944. Censors limited shows. Curfew meant shows started earlier. In summer 1943, 75,000 people attended shows in Guernsey.

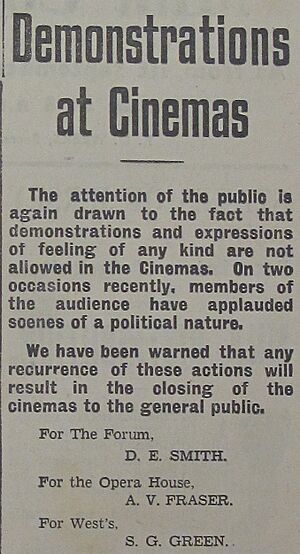

Cinemas stayed open. German soldiers and civilians sat in separate areas. The number of films was limited. Jersey and Guernsey exchanged films. French and German films from the continent were also shown. When Allied soldiers were shown, even as prisoners, the local audience would cheer. Civilian interest in cinema dropped when English films ran out.

Dance classes continued. Dances with German soldiers and local girls happened from 1942. But in 1943, they were banned in Jersey due to illness. A dance show in Guernsey attracted 500 people per performance for two weeks.

Boxing tournaments were popular. So were Beetle Drives. Pubs stayed open with reduced hours and limits on strong drinks. Card games, darts, and shove ha'penny were popular.

Sports were also popular and helped relieve boredom. But food shortages later meant people lacked energy to play. Sometimes, games were followed by a visit to a pub for a small drink. One football match drew over 4,000 people. There were recorded games against German teams. A football game in July 1940 was won by Guernsey. Sports also included cricket, baseball, and rugby.

With the curfew, home entertaining had to finish earlier. If not, everyone stayed the night and went home the next morning.

From June 6, 1944, all entertainment and theatres closed. Curfew was extended from 9 PM to 6 AM. People had to be careful not to show lights at night. German soldiers were known to shoot at lit windows.

Clubs

Many clubs could stay open after getting permission. A few were exceptions, like the Salvation Army and children's clubs such as the Scouts. The Freemasons were closed down. But they avoided persecution, unlike elsewhere. Their property was stolen, and buildings damaged. Sometimes, there were limits on how many people could meet. This happened after large crowds attended military funerals for drowned British sailors.

Transport and Fuel

Petrol rationing started quickly. Civilian cars and motorcycles stopped running within days. A limited bus service ran for a while. Some delivery vans were allowed. Bicycles became the main way to get around. But strong bikes were taken by the Germans.

Horses and carts were used again for transport. Old prams were used to carry heavy goods. Attaching a basket to a walking stick also helped.

Petrol and Vehicles

Petrol was rationed from July 1940. Civilian cars almost stopped. Doctors were an exception. Some people switched to motorcycles to stretch their fuel ration. Vehicle mileage had to be reported. This was to prevent black market fuel use. People disconnected speedometers to avoid being caught.

Many vehicles were taken by the Germans and sent to France. Over 100 buses, cars, vans, lorries, and even an ambulance were changed to run on wood gas. This gas was made from charcoal and wood, using Gazogene units.

Heating, Lighting, and Cooking

Coal could not be imported from June 1944 and ran out three months later. Small amounts of peat were cut for fuel. Gas was restricted from 1941. It was limited by appliances and hours of availability. It ran out completely in December 1944.

Electricity restrictions started in April 1942. Usage and hours were limited. The supply stopped in February 1945. The lack of power for pumping restricted piped water supply.

Cutting wood was restricted from the start. It was rationed from July 1941. Gathering wood needed a permit, even on your own land. Late in the war, people started stripping wood from empty houses. They also burned furniture. In December 1944, a household of 6 people with no gas or electricity was allowed 224 pounds of wood a week. The scenery changed by the end of the war. Thousands of trees had been cut down across the islands.

Paraffin lamps were made from tins. Paraffin was only allowed for lighting. Supplies ran out in July 1944. Candles were scarce. Households were allowed only one per week. Matches were also very scarce.

The old tradition of taking food in pots, like Bean Jar, to bakers to cook in their cooling ovens was encouraged. This cost a small fee.

Haybox cooking became popular. Food was heated in a pot. Then the pot was placed in a box packed with hay. It cooked slowly for hours without more fuel.

Furze ovens were used again in old farmhouses. Communal kitchens were set up as early as 1940. Jersey's commercial kitchens produced 400,000 meals by the end of 1943. The States of Jersey supplied over 2,000,000 pints of soup. Guernsey relied more on volunteers.

Sawdust stoves were made from a tin. Compacted sawdust mixed with tar was burned to create heat.

Communication

All outside telephone links were cut within days of the occupation. All radio transmitters were seized. Post was disrupted and censored. At first, no post was allowed outside the islands. English postage stamps were still used. When they ran out in 1941, 2d stamps were cut in half to make 1d stamps. Both islands printed local stamps. Jersey's included the royal symbol GR.

In September 1940, only 220 letters were allowed to be sent from Jersey via the Red Cross. The Germans first refused to accept letters to anyone who had left the island before the invasion.

In Guernsey in 1940, the Germans suggested recording a message to be broadcast over radio. This was so people in Britain could listen. The message recorded by Ambrose Sherwill caused controversy. It mentioned the good behavior of German soldiers. It said the population was well looked after. This was not how Churchill wanted Germans to be seen. But it would have comforted islanders in Britain.

During the occupation, no civilians had a radio transmitter. England did not try to deliver one.

Telephone calls were listened to. Not many people had phones. Civilian phone use stopped in June 1944. Even emergency services stopped using phones from January 1945.

Red Cross Messages

Red Cross messages became very important. They usually went through Germany, then Sweden or Portugal. They could take weeks or months to arrive. The number of words was limited and checked. Many islanders put secret codes in their messages to family. Many Red Cross letters were published in a monthly magazine in England.

Restrictions on messages were slowly lifted. The number of words increased from 10 to 25. People could send more cards more often. Messages were eventually mailed to recipients instead of having to be picked up.

Nearly one million messages were handled by volunteers. This was before the islands were cut off in late 1944.

Censorship and Radios

Newspapers were censored from the start. Papers often had articles written by Germans pretending to be editors. The bad English in "German" articles showed they were propaganda. When people could listen to the BBC, it was clear who was telling the truth. A Jersey paper written in Jersey French caused problems for the Germans. They could not translate it, so it stopped being printed.

Paper became scarce. Newspapers became smaller, sometimes just one page. Then they printed every other day. Official announcements were displayed in shop windows.

Secret news sheets were printed to share news from the BBC. Most people involved were arrested. Many died in prisons. Allied propaganda leaflets were not dropped after summer 1940. In autumn 1944, leaflets were dropped to encourage Germans to surrender.

Libraries were popular and stayed open. Some books were removed due to censorship.

For the first four months, radios were allowed. People could listen to the BBC. Then, after a small commando raid, 8,000 radios were taken in Guernsey alone. It was easy to find owners because almost everyone had a BBC radio license. Radios were returned in December 1940. But they were taken again in June 1942 for "military reasons." This happened after a big bombing raid on Cologne.

If people had more than one radio, they might hide one. Or they handed in an old, broken one. Other people made simple crystal radio sets. It was possible to make crystals. Wire was available. The hardest part was a speaker. Stripping down telephone receivers solved that problem.

Radios and crystal sets had to be well hidden. Listening to them had severe penalties. This included up to six months in prison and a heavy fine. Several people were imprisoned. Some died, like Frederick William Page.

The BBC did not broadcast programs for Channel Island civilians. They feared revenge against the islanders. This made islanders feel forgotten. But in July 1940, a message about evacuated children was broadcast. On April 24, 1942, another message was sent. 20-minute programs were planned for Christmas Day in 1941 and 1942. But it is not known if they were broadcast.

Health and Resistance

Medical Treatment

Life under occupation meant less heating, warm food, dry clothing, and soap. The poor diet led to more minor illnesses. These included dysentery, head lice, and scabies. Major illnesses like typhus, brought by Russian OT workers, also increased. This caused several deaths. Typhoid and infectious hepatitis became more common as the war went on. Clean water became scarce.

Ambulances changed from motorized to horse-drawn wagons. Doctors, dentists, nurses, and St John ambulance staff worked closely. They treated civilians, soldiers, and OT workers. From 1942, there were restrictions on helping injured German soldiers. Each group had its own hospital.

An outbreak of diphtheria in Jersey quickly used up all the antitoxin. It was controlled by isolating people and banning public gatherings. Medical supplies were made locally when possible. Bandages were made from torn sheets. Moss was used instead of cotton wool. Some medicines came from France. A few supplies, like insulin, came from the Red Cross after 1942. But it was too late for 30 patients in Jersey.

Babies born during the occupation received the best care available. Midwives in Jersey learned how Soviet OT workers gave birth and wrapped their babies.

Malnutrition became common. Many civilians lost up to 40% of their body weight. This led to related illnesses like swelling, bad teeth, and tuberculosis. The death rate in Jersey in January 1945 was three times higher than normal.

Resistance Efforts

Despite harsh punishments, some resistance happened. Several civilians died in prisons. There were few acts of active resistance. Little damage was done to the German forces.

The most visible act of passive resistance happened in Guernsey. This was after two British ships, HMS Charybdis and HMS Limbourne, sank on October 23, 1943. The bodies of 21 British sailors washed ashore. The funeral attracted over 20% of the population. They laid 900 wreaths. This was such a strong show against the occupation that Germans banned civilians from future military funerals. The ceremony is remembered every year.

Islanders also served in Allied forces. The islands' biggest impact on the Nazis was absorbing large amounts of concrete and steel. They also kept 30,000 German troops busy. These troops could have been used elsewhere.

One French artillery piece brought to the island in 1942 may have been sabotaged in France. Its barrel exploded when fired, killing several German marines.

Collaboration and Friendships

Working with the Germans

No islanders joined active German military units.

Some people, like Eric Pleasants and Dennis Leister, were in prison for burglary when the Germans arrived. They offered to work as spies for the Germans. They were sent to France. Leister was rejected and sent to a concentration camp, but he survived. Chapman was accepted and trained as a spy. When he landed in Britain, he turned himself in. He became a British double agent. He ended the war with a German medal and money from British intelligence.

Pearl Vardon, a Jersey teacher, spoke German. She worked as an interpreter for a German company. She became involved with a German officer. When he was sent to Germany, she went with him. Vardon worked as an announcer for a German radio station. She read letters from British prisoners of war to their families. A German colleague said she "simply hated all things English and loved all things German." Vardon was later jailed for nine months for helping the enemy.

John Lingshaw from Jersey was sent to a camp in Germany in 1942. In August 1943, he volunteered to teach English to German propaganda workers. After the war, he was sentenced to five years in prison.

Informers

Some anonymous letters were sent to German authorities. They reported islanders for crimes. These letters might have been for personal reasons, not just collaboration. A few letters were stopped by the post office head. He would open them, read them, and then "lose" them or delay them. This gave the accused a warning. Other letters were not anonymous. People were attracted by the reward offered by the Germans. On Sark, an islander nailed a list of people with illegal radios to a tree. The German commander was shocked by this betrayal and did not act on the information.

People were arrested, imprisoned, and died after being reported. Louisa Gould was one. She had hidden an escaped German slave worker. She was reported by two elderly spinsters living next door. They sent an anonymous letter. These women were not prosecuted after the war. But they were avoided by everyone for the rest of their lives. Informers were hated more than the Germans by civilians.

Friendship and Relationships

Being civil to each other was expected. Germans attended islanders' cricket matches. Cinemas had separate areas for Germans and civilians. The German army often held public music concerts. Dances were held, and local ladies were invited. A few families became friendly with specific soldiers or workers. More than 20 Spanish workers stayed and married Jersey women after the war.

After liberation, the British commander heard many stories of collaboration. Talks of "lobster dinners" for Germans were dismissed. Most accusations were seen as rumors and gossip.

Help for Civilians

In August 1944, Germany offered to release and evacuate all Channel Island civilians. This excluded men of military age. Britain considered the offer. Winston Churchill reportedly said, "Let 'em starve. They can rot at their leisure." It is unclear if he meant the Germans or the civilians. In late September, the offer was rejected.

In November, the Germans agreed with the Bailiff of Jersey to send a message to Britain. It detailed the food levels for civilians. Britain then agreed to send Red Cross parcels. It was very unusual for Red Cross parcels meant for prisoners of war to be given to civilians.

The ship SS Vega arrived in Guernsey on December 27 and Jersey on December 31. It brought 119,792 food parcels, salt, soap, and medical supplies. More relief supplies arrived monthly until liberation. These parcels saved many civilian lives.

Liberation and Aftermath

For several weeks, liberation was expected. At dawn on May 9, 1945, Allied ships were seen from Guernsey. Crowds gathered. A few British troops landed to great celebrations. German troops stayed in barracks. Some ships went to Jersey to officially land and accept the German surrender. By May 12, men, vehicles, and supplies were pouring ashore.

After the initial joy, the hard work of getting the islands "back to normal" began. Food, clothing, medicines, and basic items, even toilet paper, were brought in. Harbours had to be cleared of mines. German soldiers were shipped out on the now empty landing ships. Weapons and ammunition were collected. Civilians went souvenir hunting for pistols, daggers, and medals. Military equipment was gathered. Mine clearing took months. Mines are still found today.

The 20,000 evacuees started to return in batches from July. 2,000 deportees returned in August. Many children were very young when they left five years earlier. They hardly knew their relatives. Many could no longer speak the local Patois language. Many evacuees felt treated as second-class citizens by those who stayed. This was because they had left in 1940. Men and women who joined the armed services returned mostly in 1946. Relationships were difficult at first. Returned children did not understand why food should not be thrown away. They even ate apple cores.

Accusations and complaints flew around. Some civilians were angry at the Germans. Some were angry at the British for abandoning them. Many were angry at other civilians for their behavior. Investigators looked for war crimes. Most civilians looked for work. They rebuilt their strength with better food and medicines. They tried to pick up their lives after five years of occupation. There was also much work to do repairing damaged houses.

After spending years in prisoner of war camps in the UK, a few Germans returned to marry their island sweethearts. So did some OT workers. They received mixed reactions from islanders.

After Liberation

The island governments were bankrupt. They had to pay for the occupation. The British government helped with a grant. Rationing, like in the UK, continued until 1955.

A conference decided how to define collaboration:

- (a) Women who associated with Germans.

- (b) People who entertained Germans or had social contact with them.

- (c) Profiteers (people who made unfair profits).

- (d) People who gave information to Germans.

- (e) People who worked for Germans.

No official action was taken for groups (a) and (b). Social disapproval was enough. Group (c) was dealt with through taxes. Groups (d) and (e) could face serious charges. British intelligence concluded that few English people worked for the Germans. They were often forced to some extent.

After liberation, claims of collaboration were investigated. By November 1946, most claims were found to be without strong evidence. Only 12 cases were considered for prosecution. But prosecutors decided there were not enough legal grounds. Especially for those accused of informing on fellow citizens. The only trials related to the occupation were against people who came to the islands from Britain for farm work in 1939-1940. These included conscientious objectors and people of Irish descent.

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited the islands on June 7, 1945. Field Marshall Lord Montgomery visited in May 1947. Winston Churchill was invited twice but did not visit.

The island bailiffs were cleared of all accusations of being "Quislings" (traitors) and collaborators. Both were knighted in 1945 for their service. Other people also received honors. Only those who lived through the occupation could truly understand those five long years.

Laws passed during the occupation needed to be made legal. In Jersey, 46 laws were officially approved after liberation.

Germans were investigated, especially regarding deportations. The outcome was that no war crimes had been committed in Jersey, Guernsey, or Sark. However, for Alderney, a court case was recommended for the mistreatment and killing of OT slave workers. No trial ever took place in Britain or Russia. But two OT overseers were tried in France and jailed for many years.

Deaths during the occupation:

- German forces: about 550

- OT workers: over 700 (500 graves and 200 drowned when a ship sank)

- Allied forces: about 550 (504 from the sinking of HMS Charybdis and HMS Limbourne)

- Civilians: about 150 (mainly from air raids, deportations, and prisons; this does not include deaths from malnutrition and cold)

A higher percentage of civilians died in the islands compared to the UK's population.

Of the people who left the islands in 1939/40 and were evacuated in 1940, 10,418 islanders served with Allied forces.

- Jersey citizens: 5,978 served, 516 died.

- Guernsey citizens: 4,011 served, 252 died.

- Alderney citizens: 204 served, 25 died.

- Sark citizens: 27 served, one died.

A higher percentage of serving people from the islands died compared to the UK's population.

Images for kids

See also

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |