Vidkun Quisling facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Vidkun Quisling

|

|

|---|---|

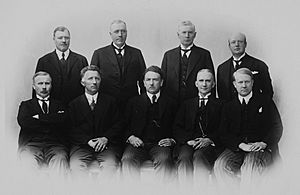

Quisling, c. 1919

|

|

| Minister President of Norway | |

| In office 1 February 1942 – 9 May 1945 Serving with Reichskommissar Josef Terboven

|

|

| Preceded by | Johan Nygaardsvold (as Prime Minister) |

| Succeeded by | Johan Nygaardsvold (as Prime Minister) |

| Minister of Defence | |

| In office 12 May 1931 – 3 March 1933 |

|

| Prime Minister | Peder Kolstad Jens Hundseid |

| Preceded by | Torgeir Anderssen-Rysst |

| Succeeded by | Jens Isak Kobro |

| Fører of the National Gathering | |

| In office 13 May 1933 – 8 May 1945 |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Jonssøn Quisling

18 July 1887 Fyresdal, Telemark, Sweden-Norway |

| Died | 24 October 1945 (aged 58) Akershus Fortress, Oslo, Norway |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Political party |

|

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Profession | Military officer, politician |

| Signature |  |

Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Jonssøn Quisling (18 July 1887 – 24 October 1945) was a Norwegian military officer and politician. He became known as a Nazi collaborator during World War II. He led the government of Norway while it was occupied by Nazi Germany.

Quisling first gained attention by working with explorer Fridtjof Nansen. He helped organize aid during a terrible famine in Russia in 1921. He also worked as a Norwegian diplomat in the Soviet Union. In 1929, he returned to Norway. He served as Minister of Defence from 1931 to 1933.

In 1933, Quisling started his own political party, the fascist Nasjonal Samling (National Union). His party did not win many votes. On April 9, 1940, when Germany invaded Norway, he tried to take power in a radio broadcast. This attempt failed because the Germans did not support his government at that time.

Later, from 1942 to 1945, he became the Prime Minister of Norway. He led the Norwegian government alongside the German administrator, Josef Terboven. His government worked with Germany and was called the Quisling regime. This government helped send Jewish people out of Norway to concentration camps.

After World War II, Quisling was put on trial. He was found guilty of serious crimes, including high treason against Norway. He was sentenced to death and executed on October 24, 1945. Since then, his name "quisling" has become a word meaning "traitor" or "collaborator" in many languages.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Growing Up in Norway

Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Jonssøn Quisling was born on July 18, 1887. His birthplace was Fyresdal in Telemark, Norway. His father, Jon Lauritz Qvisling, was a pastor. His mother was Anna Caroline Bang. The family name comes from a Latinized name, Quislinus. This name was created by an ancestor from a village in Denmark.

Vidkun was a quiet but helpful child. He had two brothers and a sister. His family moved to Drammen and then to Skien. He went to school for the first time in Drammen. He was a very good student, especially in history and mathematics.

Military Career and Russia

In 1905, Quisling joined the Norwegian Military Academy. He scored the highest on the entrance exam that year. He then went to the Norwegian Military College. He graduated with the best score since the college started in 1817. He joined the army's General Staff in 1911.

During First World War, Norway stayed neutral. In 1918, Quisling was sent to Russia. He worked at the Norwegian office in Petrograd. He had studied Russia for five years. He saw the difficult living conditions there. He believed the Bolsheviks had strong control over Russian society. When he returned to Norway, he became the army's expert on Russian affairs.

Travels and Early Political Ideas

Working with Fridtjof Nansen

In 1919, Quisling went to Helsinki as an intelligence officer. In 1921, he joined explorer Fridtjof Nansen to help with aid efforts. He went to Kharkiv in Ukraine in 1922. He helped with humanitarian relief for the League of Nations. Quisling wrote a report about the terrible situation. His report helped bring aid and showed his good organizing skills.

On August 21, 1922, he married Alexandra Andreevna Voronina. Later, he met Maria Vasiljevna Pasetchnikova. He claimed to have married Maria in 1923, though there is no official record. The three of them left Ukraine.

Returning to Norway

Quisling spent some time in Paris, studying political ideas. He also worked on his own philosophy called Universism. In 1923, he wrote an article for a newspaper. It asked for official recognition of the Soviet government.

In 1924, Quisling returned to Norway. He became interested in the communist labor movement for a short time. He even suggested a people's militia to protect the country. Historians say his views at this time were a mix of socialism and nationalism.

Entering Politics

Plans for Change

Quisling returned to Norway in late 1929. He had a plan for change called Norsk Aktion (Norwegian Action). This plan involved a new organization. It would have national, regional, and local groups. He wanted to change Norway's government. He suggested a two-chamber parliament with elected representatives.

He also sold many antiques and artworks he bought cheaply in Russia. His collection included paintings said to be by famous artists. In 1930, he joined up with his friend Prytz. They started attending meetings with officers and business people. These meetings aimed to launch Quisling into politics.

After Fridtjof Nansen died in May 1930, Quisling wrote an article about him. He outlined ten points for Norway, including "strong and just government." He also wrote a book, Russia and Ourselves. This book was against Bolshevism and was openly racist. It made Quisling well-known in politics. He and Prytz then started a new political movement. It was called Nordisk folkereisning i Norge (Nordic popular rising in Norway). Quisling became its leader, or fører.

Becoming Defence Minister

In May 1931, Quisling became the Minister of Defence. He joined the government of Peder Kolstad. This was a surprise because he wasn't a member of Kolstad's party. His first big action was dealing with a labor dispute called the Battle of Menstad. He sent in troops to handle it.

Quisling was concerned about communists. He made a list of union leaders he thought were causing trouble. Some of them were charged with crimes. He also started a permanent militia called the Leidang. This group was meant to be against revolution.

In 1932, Quisling was attacked in his office. Someone threw pepper in his face. Some newspapers suggested it was staged. Others thought it was a jealous husband. The "pepper affair" made people have strong opinions about Quisling.

After Kolstad died, Quisling stayed as Defence Minister under Jens Hundseid. He used a chance to speak in Parliament to attack the Labour and Communist parties. He called some members "enemies of our fatherland." This made many right-wing people support him. Tens of thousands of Norwegians called for his claims to be investigated. Quisling gave many speeches to large crowds that summer.

Leading a New Party

In 1933, Quisling's movement became a political party. It was called Nasjonal Samling (National Unity), or NS. The party was ready for the upcoming election. Quisling wanted to lead a national movement, not just one party.

Nasjonal Samling believed in a strong leader, like the Nazi Führer. It also used strong propaganda. The party gained support from some wealthy people in Oslo. It also got help from the Norwegian Farmers' Aid Association.

Quisling was not a great speaker. But his reputation for scandals made people aware of his party. In the October 1933 elections, the party got about two percent of the national vote. It did not win any seats in Parliament. This made it the fifth largest party in Norway.

Party Decline

After the election, Quisling became less willing to compromise. His party started to develop its own form of national socialism. But without a leader in Parliament, they struggled to make big changes. When Quisling tried to introduce a bill, it was quickly rejected. The party then began to decline.

In 1935, Quisling made a threat. He said "heads [would] roll" when he gained power. This statement badly hurt his party's image. Several important members left the party.

Quisling started to connect with international fascist movements. He attended a fascist conference in 1934. He also met Nazi thinker Alfred Rosenberg. By the 1936 elections, his opponents called him the "Norwegian Hitler." This was partly because of his strong anti-Semitic views. He linked Jewish people with Marxism and other things he disliked. His party also became more like the German Nazi Party.

Despite his hopes, Nasjonal Samling got even fewer votes in 1936. The party split, and many members left. Quisling also faced money problems. Many of his paintings turned out to be copies. He became very disappointed with Norwegian society.

World War II

Preparing for War

In 1939, Quisling focused on Norway's defense. He believed Norway needed to spend more on its military. This would help it stay neutral in the coming European war. He also supported Adolf Hitler. He thanked Hitler for "saving Europe from Bolshevism and Jewish domination." Quisling thought Norway should side with Germany if neutrality was impossible.

He visited Germany in the summer of 1939. He was well-received. Germany promised money to help Nasjonal Samling grow in Norway. When war started in September 1939, Quisling felt his ideas were proven right.

In December 1939, Quisling met Hitler. Hitler promised to respond if Britain invaded Norway. He also said Quisling would get money for his party. The two met again. Quisling wrote a note saying he was not a National Socialist. Quisling was kept out of the loop as Germany planned its invasion.

On April 8, 1940, British forces began an operation in Norway. This brought Norway into the war. Quisling expected a quick German response.

German Invasion and Coup Attempt

On April 9, 1940, Germany invaded Norway. They planned to capture the King and the government. But the government escaped. A German ship carrying administrators was sunk. The Germans expected Norway to surrender, but it did not.

Quisling and his German contacts decided a quick takeover was needed. Quisling was told that Hitler would approve if he formed a government. Quisling made a list of ministers. He claimed the real government had "fled."

The Germans occupied Oslo. At 7:30 PM, Quisling went on Norwegian radio. He announced he had formed a new government and was Prime Minister. He also canceled an order to fight the German invasion. But his orders to arrest the government were ignored. Hitler recognized Quisling's government within 24 hours. Quisling even agreed to a German request to stop Norwegian resistance. This made it seem like his takeover was part of the German plan.

Quisling was at the peak of his power. But on April 10, the German ambassador met with King Haakon. He demanded the King appoint Quisling as head of government. King Haakon refused. He said he would rather give up his throne. The government supported the King and urged continued resistance.

With no popular support, Quisling was no longer useful to Hitler. Germany withdrew its support for his government. Quisling's reputation hit rock bottom. He was seen as a traitor and a failure.

Leading the Government

Since the King rejected the German commission, Hitler appointed Josef Terboven as the new German Governor-General of Norway. Terboven reported directly to Hitler. Terboven did not want Quisling in the government. But Hitler insisted Quisling have a role.

Quisling returned to Norway in August. He had convinced Hitler to let him lead the government. Terboven had to agree. He announced that Nasjonal Samling would be the only allowed political party.

By the end of 1940, the monarchy was suspended. Quisling became acting prime minister. Ten of the thirteen ministers were from his party. He wanted to get rid of democratic ideas like pluralism. He gave more power to mayors who joined Nasjonal Samling. The party's membership grew to over 30,000.

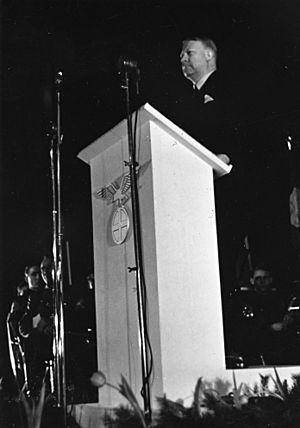

In December 1940, Quisling went to Berlin. He agreed to raise Norwegian volunteers to fight with the German Schutzstaffel (SS). He believed that if Norway helped Germany, it would not be taken over. He also made Norwegian policy on Jewish people align with Germany's. He gave a speech in March 1941, arguing for forced exile.

In May, Quisling's mother died, which affected him deeply. Political problems over Norway's independence continued. Quisling threatened to resign. In the end, he had to allow a German SS brigade in Norway.

The government became stricter. Communist leaders were arrested. Trade unionists were threatened. In September 1941, two men were executed after a strike. This event was seen as a turning point. The Statspolitiet (State Police) was brought back to help the Gestapo. Radios were taken from people. Quisling supported these actions.

In January 1942, Quisling was officially made Minister-President of the national government. This gave him more power. He committed his government to closer ties with Germany. The only change to the Constitution was bringing back the ban on Jewish people entering Norway.

Minister President's Actions

Quisling's new position gave him more security. In February 1942, he visited Berlin. He discussed Norway's independence. But German officials like Joseph Goebbels were not convinced he would be a great leader.

Back in Norway, Quisling wanted to improve his party's membership. On March 12, 1942, Norway officially became a one-party state. Criticism of the party was made illegal.

However, Quisling lost public support in the summer of 1942. He tried to force children into the Nasjonal Samlings Ungdomsfylking, a youth group like the Hitler Youth. This led to many teachers and church leaders resigning. There was also widespread public unrest. Quisling told Norwegians the new regime would be forced on them. Germany noted that "organized resistance to Quisling has started." Peace talks between Norway and Germany stopped. Hitler told Quisling that Norway would not get the independence he wanted.

Quisling had wanted a new parliament called a Riksting. But he changed his mind. Support for Nasjonal Samling and Quisling decreased. German actions, like shooting ten people in Trøndelag, also hurt morale.

With Quisling's involvement, Jewish people were registered in Norway. On October 26, 1942, German forces and Norwegian police arrested 300 Jewish men. They were sent to concentration camps. Their property was taken by the state. On November 26, these people and their families were deported to camps in Poland. Quisling led the public to believe this was his idea. Another 250 were deported in February 1943. It is unclear what Quisling truly knew about their fate. He may have believed they were going to a new Jewish homeland.

Quisling wanted to regain Hitler's respect. He tried to raise Norwegian volunteers for the German war effort. He believed Norway had a role in keeping the German empire strong. In April 1943, he criticized Germany for not outlining its post-war plans for Europe. Hitler did not change his mind. Quisling felt betrayed.

In the final years of the war, Quisling passed many laws. He focused on social policy. Despite the war going badly, Nasjonal Samling remained in power. However, Germany took more control over law and order in Norway. After deporting Jewish people, they deported Norwegian officers and students.

On January 20, 1945, Quisling made his last visit to Hitler. He offered Norwegian support if Germany agreed to a peace deal. He feared that as German forces retreated, his government would lose control. But the Nazis decided to use a scorched earth policy in northern Norway. They even shot civilians who refused to leave. Quisling refused to sign an order to execute thousands of Norwegian "saboteurs." This angered Terboven. Quisling cried to a friend, believing this refusal would seal his reputation as a traitor.

Quisling spent the last months of the war trying to prevent more Norwegian deaths. He worked to bring Norwegians from German prisoner camps home. He privately knew that National Socialism would be defeated. After Hitler's suicide, Quisling offered to share power with the government-in-exile.

On May 7, Quisling ordered police not to fight the Allied advance. The same day, Germany surrendered. Quisling's position was hopeless. On May 8, he met with resistance leaders to discuss his arrest. He said he could have kept fighting but chose not to, to avoid turning Norway into a battlefield. He wanted a peaceful transition. The resistance promised fair trials for all Nasjonal Samling members.

Arrest and Trial

On May 9, 1945, Quisling and his ministers surrendered to the police. Quisling was taken to Cell 12 in Oslo's main police station. After ten weeks, he was moved to Akershus Fortress to await trial. His lawyer, Henrik Bergh, believed Quisling thought he was acting in Norway's best interests.

Quisling was charged with several crimes. These included his coup attempt, helping the enemy, and trying to change the constitution illegally. He was also accused of murder. He denied the charges, saying he always worked for a free Norway. In July 1945, more charges were added. These included more murders, theft, and conspiring with Hitler for the invasion.

Trial and Execution

The trial began on August 20, 1945. Quisling's defense tried to show he was not fully united with Germany. He claimed he fought for Norway's independence. But this was hard to believe for many Norwegians. He often twisted the truth.

During the trial, Quisling's health suffered. The prosecution blamed him for the deportation of Jewish people in Norway. They used testimony from German officials. The prosecutor asked for the death penalty. This was allowed by new laws passed by the government-in-exile.

On September 10, 1945, Quisling was found guilty of most charges. He was sentenced to death. His appeal to the Supreme Court was rejected. The trial was considered fair.

Quisling was executed by firing squad at Akershus Fortress on October 24, 1945. He was shot at 2:40 AM. His last words were, "I'm convicted unfairly and I die innocent." His body was cremated, and his ashes were buried in Fyresdal.

Legacy

Quisling's wife, Maria, lived in Oslo until she died in 1980. They had no children. She donated their Russian antiques to a charity. Quisling lived in a large house in Oslo called "Gimle." This name came from Norse mythology. The house is now a Holocaust museum.

The Nasjonal Samling party disappeared as a political force in Norway. Quisling became one of the most written-about Norwegians. The word "quisling" became a common term for "traitor." The British newspaper The Times first used the term on April 15, 1940. For a while, people even used the verb "to quisle" to mean committing treason.

Personality

Quisling's supporters saw him as a careful and knowledgeable leader. They believed he cared deeply for his people. His opponents saw him as unstable and rude. He was likely shy and quiet with strangers but could be dramatic under pressure. He often suspected larger groups were plotting against him.

After the war, people had mixed views of his character. He was seen as weak, paranoid, and power-hungry. One psychiatrist described his goals as fitting the description of a "paranoid megalomaniac."

While in office, Quisling worked long hours. He liked to be involved in almost all government matters. He read many letters himself. He was independent and made decisions quickly. He also liked to follow proper procedures. He took a special interest in his hometown, Fyresdal.

He did not believe in German racial superiority. He thought the Norwegian race was important for Northern Europe. He even researched his own family tree. Party members did not get special treatment. Quisling did not live a lavish life, and many gifts he received went unused.

Religious and Philosophical Views

Quisling was interested in science, Eastern religions, and philosophy. His library had books by famous thinkers like Spinoza and Kant. He followed new ideas in quantum physics. He combined philosophy and science into his own idea called Universism. This was his way of explaining everything. He wrote thousands of pages on it. He rejected traditional Christian teachings. He borrowed the term Universism from a book about Chinese philosophy.

His main work was never finished. It was meant to explain how humans progress and his ideas on morality, law, science, and politics. Historians say he would not have been recognized as a philosopher.

During his trial, Quisling became interested in Universism again. He saw the war as part of a plan for God's kingdom on Earth. He wrote a document called Universistic Aphorisms. It was like a prophecy. He also wrote a sermon called Eternal Justice, which talked about reincarnation.

Works

- Quisling, Vidkun (1931). Russia and Ourselves. Hodder & Stoughton. https://archive.org/details/russia-and-ourselves/page/n3/mode/2up.

In Norwegian

- Quisling, Vidkun (1941). Russland og vi. Blix forlag. https://archive.org/details/russland-og-vi--.

Articles and Speeches

- Quisling har sagt — I. Citater fra taler og avisartikler. J. M. Stenersens forlag. 1940. https://archive.org/details/quisling-har-sagt-i.-citater-fra-taler-og-avisartikler.

- Quisling har sagt — II. Ti års kamp mot katastrofepolitikken. Gunnar Stenersens forlag. 1941. https://archive.org/details/quisling-har-sagt-ii.

- Quisling har sagt — IV. Mot nytt land. Artikler og taler av Vidkun Quisling 1941–1943. Blix forlag. 1943. https://archive.org/details/quisling-har-sagt-iv.

- For Norges frihet og selvstendighet. Artikler og taler 9. april 1940 — 23. juni 1941. Gunnar Stenersens forlag. 1941. https://archive.org/details/for-norges-frihet-og-selvstendighet.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Vidkun Quisling para niños

In Spanish: Vidkun Quisling para niños

- Førergarde, Quisling's personal guard

- Philippe Pétain, French Marshal whose name has been used to mean "traitor"

- Andrey Vlasov, Soviet general whose name has been used to mean "traitor"

- Mir Jafar, ruler of Bengal whose name has been used to mean "traitor"

- Robert Lundy, Scottish army officer whose name has been used to mean "traitor"

- Wang Jingwei, Chinese politician whose name has been used to mean "traitor"

- Benedict Arnold, American officer whose name has been used to mean "traitor"

- Judas, Apostle whose name has been used to mean "traitor"