Union between Sweden and Norway facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1814–1905 | |||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Anthem:

Norway: Norges Skaal (1814–1820) Sønner af Norge (1820–1864) Ja, vi elsker dette landet (de facto) Sweden: Du gamla, du fria (de facto) |

|||||||||||||||

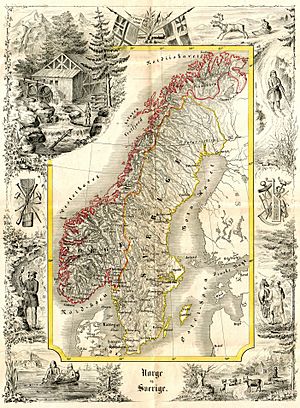

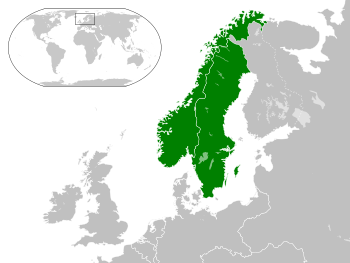

Sweden–Norway in 1904

|

|||||||||||||||

| Status | Personal union | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Stockholm and Christiania | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Sámi, Finnish | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Norway: Church of Norway (state religion) Sweden: Church of Sweden (state religion) |

||||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchies | ||||||||||||||

| King of Sweden and Norway | |||||||||||||||

|

• 1814–1818

|

Charles XIII/II | ||||||||||||||

|

• 1818–1844

|

Charles XIV/III John | ||||||||||||||

|

• 1844–1859

|

Oscar I | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Legislatures: | ||||||||||||||

|

• Swedish legislature

|

Riksdag | ||||||||||||||

|

• Norwegian legislature

|

Storting | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Between Napoleonic Wars and World War I | ||||||||||||||

| 14 January 1814 | |||||||||||||||

|

• Charles XIII of Sweden elected as King of Norway and Constitution of Norway amended

|

4 November 1814 | ||||||||||||||

|

• Monetary union

|

16 October 1875 | ||||||||||||||

|

• Union dissolved

|

26 October 1905 | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

|

• 1820

|

3,550,000 | ||||||||||||||

|

• 1905

|

7,560,000 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Sweden:

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Sweden Norway |

||||||||||||||

The United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, often called Sweden and Norway, was a special partnership between the separate kingdoms of Sweden and Norway. They shared the same king and worked together on foreign policy. This union lasted from 1814 until it peacefully ended in 1905.

Even though they had one king, Sweden and Norway kept their own separate things. They had their own constitutions (rules for how the country is run), laws, legislatures (groups that make laws), governments, churches, armies, and money. The king usually lived in Stockholm, Sweden, which is also where other countries had their ambassadors.

Norway had been closely linked with Denmark for a long time. But during the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark-Norway sided with Napoleonic France. This made the United Kingdom and Russia agree that Sweden could take over Norway. This was a reward for Sweden joining the fight against Napoleon and to make up for Sweden losing Finland in 1809.

In 1814, the Treaty of Kiel forced the King of Denmark-Norway to give Norway to the King of Sweden. But Norway didn't want this. They declared independence and created their own constitution on May 17, 1814. They even elected Prince Christian Frederick as their king.

However, a short Swedish–Norwegian War (1814) followed. The Convention of Moss then made Christian Frederick step down. The Norwegian Parliament, called the Storting, changed the constitution to allow a personal union with Sweden. On November 4, the Storting chose Sweden's king, Charles XIII, to also be the King of Norway. This officially started the union.

Over time, Norway and Sweden had disagreements. One big issue was Norway wanting its own consular service (offices in other countries to help its citizens and trade). This led to Norway declaring independence on June 7, 1905. Sweden accepted this on October 26. After a vote, Prince Carl of Denmark became the new King of Norway on November 18, taking the name Haakon VII.

Contents

- How the Union Started

- 1814: A Pivotal Year

- The Treaty of Kiel

- Norway's Fight for Independence

- The Independence Movement Grows

- Growing Opposition to Christian Frederik

- The Constitutional Assembly at Eidsvoll

- Seeking Approval at Home and Abroad

- Leading to War

- A Short War with a Surprising Outcome

- An Uncomfortable Cease-fire

- Fulfilling the Moss Agreement

- The Union in Practice

- The Union's Best Years (1844–1860)

- Leading to the End of the Union

- The Union Dissolves

- See also

How the Union Started

Sweden and Norway had been under the same ruler a few times before. But for centuries, Norway was closely tied to Denmark. It was almost like a Danish province, ruled by Danish kings from Copenhagen. Even so, Norway kept some of its own laws, army, and money.

Sweden broke away from its union with Denmark in 1523. By the mid-1600s, Sweden became a powerful country in the region. But after the Great Northern War (1700–1721), Sweden lost some of its power.

Sweden and Denmark-Norway often fought wars. During these wars, Denmark and Norway lost important areas to Sweden. Sweden also tried to take Norway from Denmark several times. These repeated wars made many Norwegians dislike Sweden.

In the 1700s, Norway became richer, especially from exporting timber to Great Britain. Wealthy Norwegians, especially timber merchants, felt that the Danish government in Copenhagen wasn't helping Norway enough. Some even thought Sweden might be a better partner. Around 1800, some important Norwegians secretly wanted to split from Denmark.

Swedish leaders also tried to connect with Norwegians who wanted to be separate from Denmark. King Gustav III of Sweden even tried to encourage a union with Sweden. But these ideas didn't become real until the Napoleonic Wars changed everything in Scandinavia.

Both Sweden and Denmark-Norway tried to stay neutral during the Napoleonic Wars. But Denmark-Norway was forced to side with France after Britain attacked the Danish navy in 1807. Since Sweden had joined Britain, Napoleon made Denmark-Norway declare war on Sweden in 1808.

Because the British navy blocked sea travel, it was hard for Denmark and Norway to communicate. So, a temporary Norwegian government was set up in Christiania (now Oslo). This showed Norwegians that they could rule themselves. Prince Christian August, an army general, led this government. He was very popular because he successfully defended Norway against a Swedish invasion in 1808.

In 1809, Sweden's king was overthrown. The Swedes chose Christian August as their new crown prince. They hoped his popularity in Norway would help them form a union with Norway, to make up for losing Finland to Russia. Christian August left Norway in 1810. After he died, Sweden chose another general, Jean Baptiste Bernadotte, who later became King Charles XIV John.

Sweden's Plan for Norway

As Crown Prince Charles John, Bernadotte's main goal was to get Norway for Sweden. He gave up Sweden's claims to Finland and joined the countries fighting Napoleon. In 1812, he secretly agreed with Russia to fight France and Denmark-Norway. Some Swedes thought it was wrong to take Norway from a weaker neighbor.

Britain and Russia also wanted Charles John to focus on defeating Napoleon first. Only after he promised to help, Britain agreed to support Sweden taking Norway in 1813. Russia and Prussia also agreed. Sweden then joined the fight against France and Denmark-Norway.

Charles John led the Allied Army and helped defeat Napoleon. Then, he marched his army towards Denmark to force the Danish King to give up Norway.

1814: A Pivotal Year

The Treaty of Kiel

On January 7, 1814, King Frederick VI of Denmark (who was also King of Norway) agreed to give Norway to the King of Sweden. This was to prevent his own country, Jutland, from being taken over by Swedish, Russian, and German troops.

This agreement was officially signed on January 14 in the Treaty of Kiel. Denmark managed to keep control of the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland. The treaty said Norway was given to "the King of Sweden," not to the Kingdom of Sweden. This was important for Norway's future king. On January 18, the Danish king told the Norwegian people they were no longer loyal to him.

Norway's Fight for Independence

Even before the treaty, Prince Christian Frederik, who was the viceroy (royal representative) in Norway, decided to keep Norway independent. He wanted to lead a Norwegian uprising. His king in Denmark secretly supported this. But publicly, the king ordered Christian Frederik to give up the border forts and return to Denmark. Christian Frederik ignored this order. He decided to claim the Norwegian throne himself, saying Norway had a right to rule itself. On January 30, his advisors agreed, starting the independence movement.

On February 2, Norwegians learned their country was given to Sweden. Most people were angry and didn't want to be ruled by Sweden. They strongly supported independence. Sweden's Crown Prince Bernadotte threatened to invade Norway and stop food supplies unless Norway accepted the Kiel Treaty. But he was busy with battles in Europe, which gave Norway time.

The Independence Movement Grows

On February 10, Christian Frederik invited important Norwegians to a meeting at Eidsvoll. He told them he wanted to resist Sweden and claim the crown. But his advisors convinced him that Norway's independence should be based on the idea of self-rule. They said he should act as a regent (a temporary ruler) for now. On February 19, Christian Frederik declared himself regent of Norway. He ordered everyone to swear loyalty to Norwegian independence and elect delegates for a special assembly at Eidsvoll on April 10.

The Swedish government immediately warned Christian Frederik that his actions broke the Treaty of Kiel and would lead to war. They said Norway would face famine and ruin. Christian Frederik sent letters to European governments, saying his actions were about Norway's desire for self-rule, not a Danish plot.

A Swedish group came to Christiania on February 24. Christian Frederik refused to accept a message from the Swedish king. He insisted on reading his own message to the Norwegian people, declaring himself regent. The Swedes called his actions reckless and illegal and left. The next day, church bells rang, and people in Christiania swore loyalty to Christian Frederik.

A Norwegian, Carsten Anker, went to London to get Britain to recognize Norway's independence. But the British Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, refused. Britain had promised Sweden support. Anker kept trying to get support from British politicians. Some members of Parliament spoke up for Norway, saying Britain shouldn't help force a free people under foreign rule. But the treaty with Sweden had to be honored.

By early March, Christian Frederik had also set up a government with different departments, though he made all the big decisions himself.

Growing Opposition to Christian Frederik

Count Wedel-Jarlsberg, a leading Norwegian noble, warned Christian Frederik that he was taking a big risk. But Wedel-Jarlsberg was accused of working with Sweden. Public opinion started to turn against the regent, with some suspecting he wanted Norway to return to Denmark.

On March 9, Sweden demanded that Christian Frederik lose his right to the Danish throne. They said European powers should go to war with Denmark if he didn't stop supporting Norwegian independence. Denmark said they didn't support Norwegian independence but couldn't control the border posts. Swedish troops gathered at the border, and rumors of invasion spread. Bernadotte called Christian Frederik a rebel. But the regent took control of all navy ships in Norway and arrested officers planning to sail them to Denmark.

On April 1, King Frederick VI of Denmark asked Christian Frederik to give up and return to Denmark. Christian Frederik refused, saying Norway had a right to self-rule.

Even though European powers didn't recognize Norway's independence, they didn't seem eager to fully support Sweden in a war. As the constitutional meeting got closer, the independence movement grew stronger.

The Constitutional Assembly at Eidsvoll

On April 10, delegates met at Eidsvoll. They elected their leaders on April 11, and debates began the next day. Two main groups formed: the "Independence party" (also called the "Prince's party") and the "Union party" (or "Swedish party"). Everyone wanted independence, but they disagreed on how to achieve it.

- The Independence party was the majority. They believed their job was only to make Norway's independence official, based on the loyalty oath taken earlier. With Christian Frederik as regent, Norway would then negotiate with Denmark as an independent country.

- The Union party was a minority. They thought Norway would be more independent in a loose union with Sweden than with Denmark. They believed the assembly should continue its work even after the constitution was finished.

The committee presented its ideas for the constitution on April 16, leading to a big debate. The Independence party won, with 78 votes to 33, to make Norway an independent monarchy. Over the next few days, there was a lot of suspicion among the delegates. They argued about whether to consider what European powers wanted.

By April 20, the idea of people's right to self-rule, pushed by Christian Magnus Falsen, became the basis of the constitution. The first draft was signed on May 1. It included important ideas like individual freedom, the right to own property, and equality.

On May 4, the assembly decided Norway would follow the Lutheran faith. The king must always be Lutheran. Jews and Jesuits were not allowed into the kingdom. But the Independence party lost when the assembly voted 98 to 11 to allow the king to rule another country if two-thirds of the legislature agreed.

The final version of the constitution was signed on May 18. But the unanimous election of Christian Frederik on May 17 is celebrated as Constitution Day in Norway.

Seeking Approval at Home and Abroad

On May 22, the new king, Christian Frederik, entered Christiania triumphantly. But there were still worries about how other countries would react. The government sent two delegates to join Carsten Anker in England to argue Norway's case.

On June 5, a British representative, John Philip Morier, arrived in Christiania. He met with the king but made it clear that Britain did not recognize Norway's independence. He said Norway should join Sweden. On June 10, the Norwegian army was called up, and weapons were given out.

On June 16, Carsten Anker wrote to Christian Frederik. He learned that Prussia and Austria were less supportive of Sweden's claim to Norway. The Russian Tsar, Alexander I of Russia, wanted a Swedish-Norwegian union but without Bernadotte as king. Britain wanted to keep Norway from falling under Russia's influence.

Leading to War

On June 26, representatives from Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Britain met in Sweden. They wanted Christian Frederik to follow the Treaty of Kiel. They were told that 65,000 Swedish troops were ready to invade Norway. On June 30, the representatives arrived in Christiania. They told Christian Frederik that Norway must join Sweden or face war with all of Europe. When Christian Frederik said Norwegians had a right to decide their own future, the Austrian representative famously said: "The people? What do they have to say against the will of their rulers? That would be to put the world on its head."

Christian Frederik offered to give up the throne and return to Denmark if Norwegians could decide their future through a special meeting of the Storting. But he refused to give the border forts to Sweden. The four-power group rejected his idea but promised to tell the Swedish king about it.

On July 20, Bernadotte sent a letter to Christian Frederik, accusing him of plotting. Two days later, he met with the delegation that had been in Norway. They encouraged him to consider Christian Frederik's terms for a union. But the Crown Prince was angry. He repeated his demand: Christian Frederik must give up his claim to the throne and the border posts, or face war. On July 27, a Swedish fleet took over some islands, starting the war with Norway. The next day, Christian Frederik refused the Swedish demand, saying it would be treason. On July 29, Swedish forces invaded Norway.

A Short War with a Surprising Outcome

Swedish forces didn't face much resistance as they moved into Norway. By August 4, the city of Fredrikstad surrendered. Christian Frederik ordered a retreat. The Swedes were stopped at the battle of Langnes, a tactical victory for Norway.

On August 3, Christian Frederik announced his decision in a meeting in Moss. On August 7, Bernadotte's representatives offered a ceasefire. It was based on the promise of a union that would respect the Norwegian constitution. Christian Frederik agreed to these terms the next day. Peace talks began in Moss on August 10. On August 14, the Convention of Moss was signed, creating a ceasefire and peace terms.

Christian Frederik made sure the agreement didn't say Norway recognized the Treaty of Kiel. Sweden agreed that the Kiel Treaty wouldn't be the basis for the future union. Bernadotte offered good peace terms because he wanted to avoid a costly war. He also wanted Norway to join the union willingly, not as a conquered land. He promised to recognize the Norwegian Constitution, with only small changes needed for the union. Christian Frederik agreed to call a special meeting of the Storting in September or October. He would then give his power to the elected representatives, who would negotiate the union terms with Sweden. Finally, he would give up his claim to the Norwegian throne and leave the country.

An Uncomfortable Cease-fire

The news was hard for Norwegians. Some were angry, some were sad about losing independence, and some were confused. Christian Frederik confirmed he would step down for "health reasons." He left his power with the state council, as agreed in Moss. On August 28, he ordered the council to accept orders from the "highest authority," meaning the Swedish king. Two days later, the Swedish king declared himself ruler of both Sweden and Norway.

On September 3, Britain announced that its naval blockade of Norway was over. Mail service between Norway and Sweden started again. The Swedish general in occupied Norway threatened to restart the war if Norwegians didn't accept the union. Christian Frederik was said to be very depressed.

In late September, Sweden and Norway argued about giving grain to the poor in Christiania. Sweden wanted it to be a gift from the "Norwegian" king. But Norway's council wanted to avoid acting like Norway had a new king before the union was official.

Fulfilling the Moss Agreement

In early October, Norwegians again refused a grain shipment from Bernadotte. Norwegian merchants borrowed money to buy food from Denmark instead. However, by early October, most people accepted that the union with Sweden was unavoidable. On October 7, a special meeting of the Storting began. On October 10, Christian Frederik gave up his throne, as agreed in Moss, and left for Denmark. The Storting temporarily took over the king's powers until the constitution could be changed.

One day before the ceasefire ended, the Storting voted 72 to 5 to join Sweden in a personal union. But they didn't vote to elect Charles XIII king yet. They waited for the necessary constitutional changes. In the following days, the Storting passed laws to keep as much independence as possible within the union. On November 1, they voted not to appoint their own consuls, which later caused problems. The Storting made the constitutional changes needed for the union on November 4. Then, they unanimously elected Charles XIII King of Norway, rather than just accepting him as king.

The Union in Practice

The new king, Charles XIII, never visited Norway. But his adopted heir, Charles John, arrived in Christiania on November 18, 1814. He accepted the election and promised to uphold the constitution for the king. He said the union was a partnership between the king and the people of Norway. He also said he valued the people's love more than rights gained through treaties. Sweden's parliament, the Riksdag of the Estates, agreed with this in 1815.

The union was based on different ideas for each country. Sweden saw it as a long-held dream, especially after losing Finland. They hoped Norwegians would eventually want a closer relationship. But Norwegians, being the smaller country, wanted to stick strictly to the agreed terms. They carefully protected every detail that showed both countries were equal.

Norway had a more democratic constitution than Sweden. The Norwegian constitution of 1814 separated the powers of the executive (king/government), legislative (Storting), and judicial (courts) branches more clearly. Norway's legislature had more power than most others in Europe. In Sweden, the king had much more power. Also, more men in Norway (about 40%) could vote than in Sweden.

Early on, a group of government officials controlled Norwegian politics. But as more farmers were elected to the Storting, they started to push for their own interests. Laws that encouraged people to participate in local government led to local self-government in 1837. This gave more citizens experience in running things.

Norway becoming more democratic eventually caused problems with Sweden. It made cooperation harder and led to the dissolution of the union between Norway and Sweden. For example, the king could completely stop a law in Sweden, but only delay it in Norway. Charles John wanted to have a complete veto in Norway, but he had to give up on that. Over time, the king's power in Norway shifted more to his Council of State. In 1884, Norway became the first Scandinavian country to have a parliamentary system. This meant the king could no longer choose his government freely or keep it in power if the Storting didn't support it. Instead, he had to appoint people from the party with the most votes in the Storting. The government also had to answer to the Storting. If the Storting voted against the government, the government had to resign. Sweden didn't get parliamentary rule until 1905, just before the union ended.

The Act of Union

The first year of the union showed that Sweden and Norway needed a clearer agreement. The main documents were the Convention of Moss and Norway's revised constitution. But Sweden's constitution hadn't changed. So, they needed a new treaty to explain how they would handle shared issues. The Act of Union (Riksakten) was negotiated in 1815. It had 12 articles about the king's power, how the two legislatures would work together, and how the governments would interact. It also confirmed that foreign policy would be decided in the Swedish cabinet, with the Norwegian prime minister present. Important union issues would be discussed in a joint meeting with all Norwegian ministers in Stockholm. The Act was passed by the Storting on July 31, 1815, and by the Riksdag on August 6. The king approved it on August 15. In Sweden, it was a regular law. But in Norway, the Storting made it part of the constitution, meaning it could only be changed like other constitutional rules.

How the Union Worked Day-to-Day

The agreements (Convention of Moss, Norwegian constitution, Act of Union) gave Norway more independence than the Treaty of Kiel had planned. Norway seemed to have joined the union willingly and insisted on being equal to Sweden. But many Swedes still saw Norway as a lesser partner, like a prize from the war.

Legally, Norway was an independent country with its own constitution. It had more internal freedom than it had in over 400 years. While it shared a king and foreign policy with Sweden, all other government parts were separate. Norway had its own army, navy, and money. The foreign service was directly under the king. This meant foreign policy was decided in the Swedish cabinet by the Swedish foreign ministry. The only Norwegian present was the prime minister. Because Swedish officials mostly handled foreign relations, outsiders often saw the union as one country. But over time, people started saying "Sweden and Norway" instead of just "Sweden."

Norway's constitution said the king should appoint his own government. Since the king usually lived in Stockholm, a part of the Norwegian government, led by the prime minister, had to be there too. The first prime minister was Peder Anker, who supported the union. The Norwegian government bought a nice house in Stockholm for its ministers, which also acted like an informal "embassy" for Norway. The other six Norwegian ministers stayed in Christiania, running their government departments. When the king wasn't in Christiania, the meetings were led by the viceroy (stattholder), who was the king's representative. The first viceroys were Swedes, which Norwegians didn't like. From 1829, the viceroys were Norwegians. The position was left empty after 1856 and finally removed in 1873.

Closer Ties or More Separation?

After Charles John became king in 1818, he tried to bring the two countries closer and give the king more power. But the Norwegian Storting mostly resisted these efforts. In 1821, the king suggested changes to the constitution. He wanted to have a complete veto (power to stop laws), more power over his ministers, and more control over the Storting. He also tried to create a new noble class in Norway. He even had military exercises near Christiania while the Storting was meeting to pressure them. But all his ideas were rejected.

The biggest political argument during Charles John's early rule was about Denmark-Norway's national debt. Norway, being poor, tried to delay or reduce its payment of 3 million speciedaler to Denmark. This caused a bitter fight between the king and the Norwegian government. The debt was eventually paid with a foreign loan, but the disagreement led to the finance minister, Count Wedel-Jarlsberg, resigning in 1821. Prime minister Peder Anker also resigned because he felt the king didn't trust him.

Norwegian politicians always responded to the king's attempts by sticking strictly to their constitution. They opposed changes that would give the king more power or lead to Norway becoming too close to Sweden. They wanted to keep their regional autonomy.

Over time, the differences and distrust lessened. Charles John became more flexible and popular. After riots in Stockholm in 1838, the king found Christiania more welcoming. While there, he agreed to some demands. In 1839, a joint committee was set up with four members from each country to solve problems between them. When the Storting met in 1839 with the king present, he was warmly welcomed.

National Symbols

Another point of disagreement was about national symbols like flags, coats of arms, royal titles, and celebrating May 17 as Norway's national day. Charles John strongly disliked the public celebration of the May constitution. He thought it was celebrating Christian Frederik's election. He tried, but failed, to encourage celebrating the revised constitution of November 4, which was when the union started. This conflict led to the Battle of the Square in Christiania on May 17, 1829. Peaceful celebrations turned into protests, and the police and army had to step in with some force. The public was so angry that the king had to allow the national day celebration from then on.

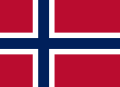

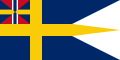

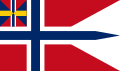

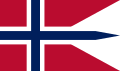

Soon after the Treaty of Kiel, Sweden added the Coat of arms of Norway to its own larger Coat of arms of Sweden. Norwegians found it offensive that it was on Swedish coins and documents, as if Norway was just a part of Sweden. They also didn't like that the king's title on Norwegian coins until 1819 was "king of Sweden and Norway." All these issues were fixed after King Oscar I became king in 1844. He immediately started using the title "king of Norway and Sweden" in all documents about Norway. A joint committee's ideas for flags and arms were put into law for both countries. A special union mark was added to the corner of all flags in both nations, combining their colors equally. Both countries got separate, but similar, flag systems, clearly showing they were equal. Norwegians were happy that the old common war flag was replaced by separate flags. The Norwegian arms were removed from Sweden's larger arms. New common Union and royal arms were created only for the royal family, foreign service, and documents about both countries. A key detail of the Union arms was that two royal crowns were placed above the shield, showing it was a union of two independent kingdoms.

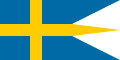

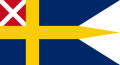

Flags

-

Union naval jack and diplomatic flag (1844–1905)

Heraldry

The Union's Best Years (1844–1860)

The mid-1800s were peaceful for the Union. All the symbol issues were solved. Norway had more say in foreign policy. The position of viceroy was often empty or held by a Norwegian. Trade between the countries grew because of treaties that allowed free trade and removed tariffs (taxes on imports). The first railway across the border, the Kongsvinger Line, made communication much faster. Sweden made concessions, leading to a more friendly political atmosphere.

The idea of Scandinavism was popular then. It suggested that Scandinavia should be a unified region or nation. This was based on the shared language, politics, and culture of the Scandinavian countries. (Norway's national anthem even calls them "three brothers.") This movement started with Danish and Swedish university students in the 1840s. At first, governments were suspicious. But when Oscar I became king in 1844, relations with Denmark improved, and the movement gained support. Norwegian students joined in 1845.

However, the movement suffered a big blow after the Second War of Schleswig in 1864. Sweden and Norway's governments made King Charles XV take back his promise of military help to Denmark. He had made the promise without asking his governments.

By then, Norwegians were losing faith in the Union. This was due to a setback over abolishing the viceroy position. King Charles XV supported Norway's wish to get rid of this symbol of dependence. He promised his Norwegian government he would approve a Storting decision to replace it with a prime minister in Christiania. The Storting almost unanimously voted for this. But when the king returned to Stockholm, Swedish newspapers reacted strongly. They said Norway was acting like a rebel. The Riksdag demanded to have a say. The main question was whether this was only a Norwegian issue or affected both countries. The conservative Swedish majority said Sweden had a "rightful superior position in the Union." King Charles had to back down when the Swedish government threatened to resign. He chose not to approve the law. But to soothe Norwegian feelings, he did it anyway in a Norwegian cabinet meeting. His actions, however, accidentally showed that he was more Swedish than Norwegian, despite his good intentions.

On April 24, 1860, the Norwegian Storting reacted to Sweden's claim of superiority. They voted unanimously that Norway alone had the right to change its own constitution. They also said any changes to the Union's terms must be based on complete equality. This decision stopped any attempts to change the Act of Union for many years. A new joint committee was formed in 1866, but its ideas were rejected in 1871. This was because they didn't give Norway equal influence on foreign policy and would have led to a federal state.

Leading to the End of the Union

Relations with Norway during King Oscar II's rule (1872–1907) greatly affected Swedish politics. More than once, it seemed the union was about to end. The main disagreements came from Norway's demand for its own consuls (officials representing the country abroad) and eventually its own foreign service. Norway had the right to separate consuls since 1814 but hadn't used it. This was partly for money reasons and partly because Swedish consuls generally did a good job for Norway. But in the late 1800s, Norway's merchant navy grew very fast. It became one of the world's largest and very important for Norway's economy. People increasingly felt Norway needed its own consuls to help its shipping and interests abroad. The demand for separate consuls also became a symbol of growing unhappiness with the Union.

In Norway, disagreements about the constitution led to the adoption of parliamentarism in 1884. This happened after a process to remove the conservative government of Christian August Selmer. The government was accused of helping the king block reforms using his veto power. King Oscar reluctantly appointed the new liberal government of Johan Sverdrup. This government quickly made important changes, like expanding who could vote and making military service required. The two opposing groups formed official political parties in 1884: Venstre (Left) for liberals who wanted to end the Union, and Højre (Right) for conservatives who wanted to keep a union of two equal states.

The liberals won a large majority in the 1891 elections. Their plan included voting rights for all men and a separate Norwegian foreign service. The new Steen government first suggested separate consular services. Negotiations with Sweden began. But the king's opposition caused several government crises. A coalition government was formed in 1895 with Francis Hagerup as prime minister. That year, a third joint Union committee was formed, but it couldn't agree on key issues and was quickly dissolved in 1898. Faced with threats from Sweden's stronger military, Norway had to drop its demands for separate consuls in 1895. This retreat convinced the Norwegian government that its armed forces had been neglected. So, they started rearming quickly. They ordered four large warships from the United Kingdom and built border fortifications.

In 1895, the Swedish government told Norway that their trade treaty from 1874 would end in July 1897. This treaty had created a good common market. When Sweden started protecting its own industries, Norway also raised customs duties. This led to much less trade between the two countries. The Swedish foreign minister, Count Lewenhaupt, who was seen as too friendly to Norwegians, resigned. He was replaced by Count Ludvig Douglas, who represented the views of the Swedish majority. However, in 1898, the Storting passed a bill for a "pure" flag without the Union badge for the third time. This time, it became law without the king's approval.

The Swedish elections of 1900 showed that the Swedish people didn't support the ultraconservative party. This led to the resignation of their leaders. On the other hand, a new party of Liberals and Radicals formed. They supported more voting rights and full equality for Norway in foreign affairs. The Norwegian elections that same year, with more people voting, gave the Liberals (Venstre) a large majority. Their plan was to have a separate foreign service and separate consuls. Steen remained prime minister but was replaced by Otto Blehr in 1902.

Last Attempts to Save the Union

The issue of separate consuls for Norway came up again. In 1902, the Swedish foreign minister suggested separate consular services, but keeping a common foreign service. The Norwegian government agreed to a new joint committee to study the issue. The promising results were published in a "communiqué" on March 24, 1903. It suggested that the rules for separate consuls and their relation to the joint foreign ministry should be set by identical laws. These laws couldn't be changed without both countries agreeing. But this was just a preliminary idea, not a formal agreement. In the 1903 elections, the Conservatives (Højre) gained many votes with their plan for reconciliation and negotiations. A new coalition government under Hagerup formed in October 1903. It had national support for reaching an agreement. The ideas from the communiqué were presented on December 11, raising hopes for a solution. King Oscar asked the governments to create proposals for identical laws.

Norway's draft for identical laws was submitted in May 1904. Sweden remained silent. While Norway had its most pro-union Storting and government ever, Swedish political opinion had shifted. The Swedish foreign minister, Lagerheim, who had supported the communiqué, resigned on November 7 due to disagreements with Prime Minister Erik Gustaf Boström. Boström then went to Christiania and presented his unexpected "principles" for a settlement. His government now insisted that the Swedish foreign minister should control Norwegian consuls and could remove them if needed. Also, Sweden should always be mentioned before Norway in official documents (breaking the practice started in 1844). The Norwegian government found these demands unacceptable and against Norway's independence. Since the foreign minister would be Swedish, he couldn't control a Norwegian institution. Further talks on these terms would be pointless.

A counter-proposal from Sweden was also rejected. On February 7, 1905, the King decided to end the negotiations he had started in 1903. Despite this, the tired king still hoped for an agreement. The next day, Crown Prince Gustaf was appointed regent. On February 13, he went to Christiania to try to save the Union. During his month there, he met with the Norwegian government and a special parliamentary committee. He begged them not to take steps that would break the union. But it was no use. The committee recommended on March 6 to continue working on laws for Norwegian consuls. The conciliatory Hagerup government was replaced by the more determined government of Christian Michelsen.

Back in Stockholm on March 14, Crown Prince Gustaf called a joint meeting on April 5. He appealed to both governments to restart negotiations based on full equality. He suggested reforms for both foreign and consular services. But he insisted that a joint foreign minister (Swedish or Norwegian) was necessary for the Union to exist. The Norwegian government rejected his proposal on April 17, saying past attempts had failed. They declared they would continue preparing for a separate consular service. But both parts of the Swedish parliament approved the crown prince's proposal on May 2, 1905. In a last effort to calm the Norwegians, Boström, who was seen as an obstacle, was replaced by Johan Ramstedt. But these efforts didn't convince the Norwegians. Norwegians of all political views now believed a fair solution was impossible. There was a general agreement that the Union had to end. Michelsen's new government worked closely with the Storting on a plan to force the issue using the consular question.

The Union Dissolves

On May 23, the Storting passed the government's plan to create separate Norwegian consuls. King Oscar, who had resumed governing, used his constitutional right to veto the bill on May 27. As planned, the Norwegian government ministers resigned. However, the king said he couldn't accept their resignation because "no other cabinet can now be formed." The ministers refused to sign his decision and immediately left for Christiania.

The King took no further steps to restore normal government. Meanwhile, the official dissolution was planned for a Storting meeting on June 7. The ministers handed in their resignations to the Storting. The Storting then unanimously passed a resolution. It declared the union with Sweden dissolved because King Oscar had "ceased to act as King of Norway" by refusing to form a new government. It also stated that since the king couldn't form a government, the royal power "ceased to be operative." So, Michelsen and his ministers were told to stay in office as a temporary government. They were given the king's executive power until the necessary changes could be made to the constitution to reflect the union's end.

Swedish reactions to the Storting's action were strong. The king formally protested. He called a special meeting of the Riksdag for June 20 to decide what to do after the Norwegians' "revolt." The Riksdag said it would negotiate the terms for dissolving the Union if the Norwegian people voted for it in a plebiscite (a direct vote by the people). The Riksdag also set aside 100 million kronor for whatever the Riksdag decided. It was understood, though not openly stated, that this money was for war if needed. The threat of war seemed real to both sides. Norway responded by borrowing 40 million kroner from France for the same unstated purpose.

The Norwegian government knew about Sweden's demands beforehand. They set a date for a plebiscite for August 13, before Sweden formally demanded it. This prevented Sweden from claiming the vote was forced by them. People were not asked to vote yes or no to the dissolution itself. Instead, they were asked to "confirm the dissolution that had already taken place." The result was 368,392 votes for dissolution and only 184 against. This was an overwhelming majority of over 99.9 percent.

After the Storting asked for Sweden's cooperation to end the Act of Union, delegates from both countries met at Karlstad on August 31. The talks were paused at one point. At the same time, Swedish troops gathered, causing the Norwegian government to mobilize its army and navy on September 13. Despite this, an agreement was reached on September 23. The main points were that future disputes would go to the permanent court of arbitration at The Hague. Also, a neutral zone would be created on both sides of the border, and Norwegian fortifications in that zone would be destroyed.

Both parliaments quickly approved the agreement. They revoked the Act of Union on October 16. Ten days later, King Oscar gave up all claims to the Norwegian crown for himself and his future family. The Storting asked Oscar to allow a Bernadotte prince to become the Norwegian king, hoping for reconciliation. But Oscar refused this offer. The Storting then offered the vacant throne to Prince Carl of Denmark. He accepted after another plebiscite confirmed the monarchy. He arrived in Norway on November 25, 1905, and took the name Haakon VII.

See also

In Spanish: Unión entre Suecia y Noruega para niños

In Spanish: Unión entre Suecia y Noruega para niños

- List of Swedish monarchs

- List of Norwegian monarchs

- History of Norway

- History of Sweden

- History of Denmark

- History of Scandinavia

- Norway in 1814

- Sweden in Union with Norway

- Union Dissolution Day