Evacuation of civilians from the Channel Islands in 1940 facts for kids

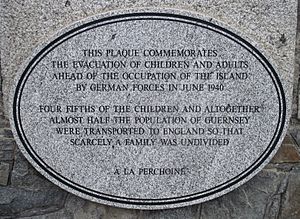

The evacuation of civilians from the Channel Islands in 1940 was a planned move of people from the Channel Islands (like Jersey, Guernsey, and Alderney) to Great Britain during World War II. This happened in stages, starting with schoolchildren, their teachers, and volunteer mothers. The islands and the British military decided to evacuate after the Allied forces lost the Battle of France, which led to the British Army leaving the islands.

Contents

Why People Left: The Background

Before the war, islanders mostly heard about European events on the radio or in newspapers. When Britain declared war on September 3, 1939, people worried more, but life stayed pretty normal. In spring 1940, the islands were even still advertised as holiday spots!

On May 10, 1940, the "Phoney War" ended, and Germany invaded Belgium and the Netherlands. The islanders had no idea their homes would be under German control for five years, until they were freed on May 9, 1945.

When it became clear that the Battle of France was lost, there wasn't much time to leave. Still, about 25,000 people went to Great Britain. Around 17,000 left from Guernsey, 6,000 from Jersey, and 2,000 from Alderney. This happened in the ten days before German troops arrived in late June 1940. Most of these civilians went to England.

Early Departures and Volunteers

In September 1939, a law called the National Service Act made it compulsory for men aged 18 to 41 in the United Kingdom to join the military. This law did not apply to the Channel Islands, which were self-governing. However, many men from the islands, especially those who had been in local military groups or college training corps, traveled to England. They volunteered and quickly joined the armed forces.

By mid-May 1940, the news was bad. Germans were fighting in France, and many individuals and families started planning to leave, taking ferries to England. Yet, some holidaymakers were still arriving! By early June, the evacuation from Dunkirk was a big topic, making more people think about leaving the Channel Islands. Paris surrendered on June 14.

Islanders were surprised when their local army units quickly left on ships with all their gear. They didn't know that on June 15, British Army leaders had decided the Channel Islands couldn't be defended. The islands were made an "open town," meaning they would not be defended militarily. This was kept secret until after the islands were bombed on June 28. The British government didn't want to invite the Germans to take the islands.

Evacuations in June 1940

Schoolchildren Leave

On June 19, the Guernsey newspaper announced plans to evacuate all children. Parents were told to go to schools that evening to sign up and get ready to send their children away the next day. Some schools asked parents to bring their child and suitcase for checking. Teachers were expected to travel with their students, and mothers volunteered to help.

Some schools moved completely, while others had their students spread out among local schools across England, Scotland, and Wales. About 5,000 schoolchildren from Guernsey evacuated, while 1,000 stayed with 12 teachers. Some children from Castel school missed their boat because of a misunderstanding about the departure time.

In Jersey, schools didn't give instructions. People could decide for themselves if they or their children should leave. Only about 1,000 children evacuated with 67 teachers, many traveling with their parents. The other 4,500 children stayed during the occupation with 140 teachers.

Other People Evacuate

Mothers with children too young for school were allowed on the first ships, as were men of military age.

In Jersey, where schoolchildren were on a two-week holiday to help with the potato harvest, everyone who wanted to leave was asked to register. Long lines quickly formed, with 23,000 people eventually signing up. The government workers couldn't handle it. Fearing riots from desperate people trying to get on ships, they announced it was best to stay. As a result, only about 1,000 Jersey children evacuated with their parents and 67 teachers.

After most of the first group left, ships became available for anyone else who wanted to go. However, authorities worried about ships being mobbed, riots, and looting in empty towns, which had happened in France. So, they pushed the message that "staying was best." Posters even said, "Don’t be yellow, stay at home." This caused confusion, especially in Jersey, where authorities thought it was safe for adults to stay since children weren't being evacuated.

People's reasons for staying or leaving were personal. Some were afraid of the unknown, while others felt it was their duty to continue fighting with Great Britain. Only a few people were pressured to leave or stay, usually because of their important jobs.

Island authorities thought that anyone who especially feared German occupation, like Jewish people, would leave. Some did, but it was later a surprise to find that others decided not to leave or were not allowed into the United Kingdom because they were considered "aliens." This meant about 20 people the Germans would define as "Jewish" became stuck on the islands.

Those who evacuated left behind houses, cars, and businesses. Some locked their doors, others didn't, thinking someone would break in anyway. Some gave away pets, others just let them go, and many put them down. Some gave away furniture or put it in storage, while others simply walked away, leaving dirty dishes and food. People could only take £20 cash from banks and just one suitcase.

The leaders of Jersey and Guernsey, called Lieutenant Governors, left their islands on ships on June 21, 1940, the day France surrendered.

Ships for Evacuation

Ships that were urgently needed to evacuate soldiers from France in Operation Aerial were sent to help civilians in the Channel Islands instead. On June 17, Marshal Philippe Pétain asked for a ceasefire, and on June 19, nearby Cherbourg was captured by German forces.

On June 21 alone, 25 ships took people from Guernsey. One was the SS Viking, built in 1905, which had served as a warship until 1918. It was used as a troopship in 1939 and carried 1,800 schoolchildren from Guernsey to Weymouth. Eighteen ships sailed from Jersey on June 21, including the SS Shepperton Ferry, which carried military supplies and 400 evacuees. Evacuation ships stopped sailing on June 23, with some ships returning to England empty. Regular cargo boats and ferries were asked to go back to normal service. Six evacuation ships were sent to Alderney on June 23, where earlier ships had docked and left almost empty. About 90% of all Channel Island evacuees were taken to Weymouth Harbour, Dorset.

Several ships, including the SS Isle of Sark, a regular cross-channel ferry, were in St Peter Port harbour on June 28 when the German air force (Luftwaffe) attacked. Six Heinkel He 111 bombers attacked Guernsey. Machine guns on the ships fired back, but it didn't seem to help. The bombs mainly damaged the harbour, where trucks loaded with tomatoes for export were lined up. Thirty-four people died. A similar attack happened in Jersey, where nine people died. That night, the Isle of Sark sailed for England with 647 refugees. It was the last ship to leave, and its Captain, Hervy H. Golding, received an award for his brave actions.

The fact that Guernsey was loading ships with tomatoes instead of just people shows there wasn't total panic. Ships from Guernsey and Jersey meant for evacuees were sometimes full, but others didn't sail with all their possible passengers. No hospital ship arrived to take the elderly and sick. Several ships, including the Guernsey lifeboat, were shot at by German planes. With enemy planes and submarines in the Channel, it was lucky that no evacuation ship was sunk.

Planes for Evacuation

RAF (Royal Air Force) units moved from Dinard in France to Jersey on June 15. No. 17 Squadron RAF and No. 501 Squadron RAF flew missions until June 19, helping with the evacuation from Cherbourg. Then, their planes flew to England, and their ground support teams were evacuated on a ferry. Other military planes used the islands. On June 17, 1940, a de Havilland Dragon Rapide plane arrived in Jersey from Bordeaux, evacuating General Charles de Gaulle from France. He had lunch while waiting for the plane to refuel before flying to London.

About 319 people evacuated the islands on five civilian de Havilland Express planes between June 16 and 19, landing in Exeter.

Life as Evacuees in the UK

Schools in New Places

When they arrived in England, the Guernsey schoolchildren were met with lots of jam sandwiches, bread and butter, and tea. Then, they had a medical check and were put on crowded, blacked-out trains. Most island children had never seen a train before. They were transported north. There were 5,000 Guernsey children with their teachers and 500 mothers who became teaching assistants.

- Elizabeth College, Guernsey first went to Oldham, then moved to Great Hucklow and Buxton in Derbyshire.

- The Intermediate School for Boys joined with Oldham Hulme Grammar School.

- The Intermediate School for Girls went to Rochdale.

- Ladies' College went to Denbigh in Wales.

- Forest and St Martin's Schools set up in Cheadle Hulme in Cheshire.

- Other primary schools managed to keep students together and settled in several small communities.

Most Alderney and Jersey schoolchildren were spread out, attending different local schools. However, students from Victoria College, Jersey gathered at Bedford School.

In the coming years, children leaving school at age 14 went into jobs, including war industries. They also joined the Home Guard, a defense force. Seventeen-year-old girls could join the ATS (women's army) or the WLA (working on farms).

Families Adjust

Some reception centers, run by groups like The Salvation Army and WVS, were surprised to find that Channel Islanders could speak English. They had arranged for French translators, but islanders often spoke their local Patois, which the translators didn't understand. Some people ignorantly asked if they had sailed across the Mediterranean or why they weren't wearing grass skirts.

Stockport received at least 1,500 refugees and later put up a blue plaque to remember the event. Others went to Bury, Oldham, Wigan, Halifax, Manchester, Glasgow, and many other towns.

Some mothers who traveled with children, whose husbands either stayed on the islands or joined the military, initially faced attempts to take their children away. It was thought they couldn't look after them without their husbands.

Women whose husbands were still on the islands were told they couldn't rent homes. So, they had to team up with a woman whose husband was in the armed services and share a house. Since they couldn't live on public assistance money, one mother would look after the children while the other went to work. Sometimes both worked, with one doing a night shift and the other a day shift.

Some houses were not good, having been previously declared unfit to live in, or were damp or bug-ridden. Others used empty shops because nothing else was available. If children or families had relatives in the UK, they often moved to them with their single suitcase of belongings to get help. Some evacuees brought an elderly relative with them. Islanders were keen to volunteer for duties like Air Raid Precautions (ARP), Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS), Home Guard, or Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) in their free time.

People in the North of England generally helped the evacuees. They were very generous, providing clothes and shoes, arranging picnics, giving free tickets to cinemas and football matches, lending furniture, and donating money for children's Christmas presents.

Staying Safe

Just because thousands had crossed the English Channel safely didn't mean they would have a safe war. Children from Manchester had recently been evacuated to Canada because that city wasn't considered safe. Channel Island children replaced them.

Those who joined the armed forces faced the usual dangers of war. Those who worked in the UK, whether in war industries or elsewhere, were at risk of bombing, just like the children.

Some Channel Island children, like some of the 1,500,000 British children evacuated from cities in 1939, faced difficult experiences. There are stories of children being made to work, their food rations being stolen, or being beaten. However, these were a small number, and most were helped by inspectors. For a few, being fostered was even better than their life at home.

The emotional impact changed many evacuees, especially children who were separated from their parents, teachers, siblings, and friends for five years. Some put up with it, even if they hated the experience. Most children had no one to talk to about their problems. It was common to blame evacuee children if something was damaged or went missing. But most children were happy, and many formed lasting friendships with the kind and caring families who looked after them.

Keeping in Touch

Channel Island refugees could not write or receive letters from people back home because their homes were now occupied by the enemy.

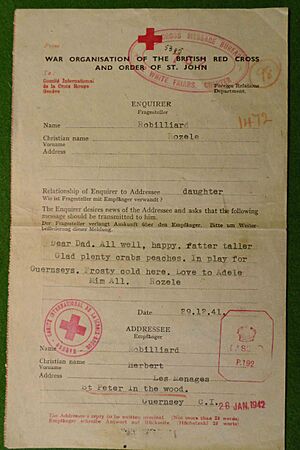

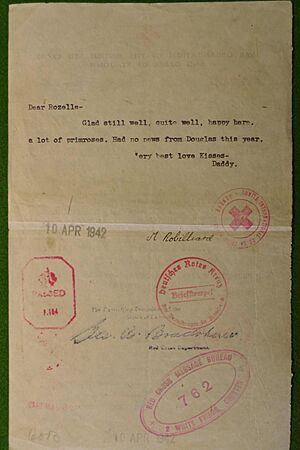

Red Cross Messages

Everyone who fled the islands left behind friends and family. With the islands under German occupation, communication was cut off. In 1941, talks allowed the International Red Cross message system, mainly for captured soldiers, to include civilians in the Channel Islands. In May 1941, the first 7,000 messages arrived in England.

Messages were first limited to 10 words per letter but later changed to 25, which was the standard for prisoners of war. The rules changed over the years. At one point, islanders couldn't write to relatives but could write to friends. The number of messages one could send was limited, and replies had to be written on the back of the original message. It could take months for a message to arrive, though a few took only weeks. All messages went through the International Red Cross headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, which handled 24 million messages during the war. The islands sent about 1 million messages, each costing 6d (old pence).

For islanders, this small link was a lifesaver. Though slow and limited, it kept important connections and reduced the fear of the unknown. However, not all messages were good, sometimes bringing sad news like "Baby Mary died last December." One family with two boys in England received the message, "Your son died in England." Messages stopped shortly after June 6, 1944, when the islands were cut off and isolated.

Channel Island Societies

The Jersey Society, founded in London in 1896, helped Jersey evacuees during the war. The society collected over 1,000 books published during the war to restock the island libraries afterward.

Over 90 local "Channel Island Societies" were set up in England. They had weekly meetings and social events, including card games and dances. Welfare groups were created to help islanders. This allowed evacuees to stay in touch, share news, support each other, and let children play together. Islanders serving in the forces would attend meetings when they could.

The Guernsey Society was formed in 1943 to represent the island's interests to the British government during the German occupation. It also created a network for Guernsey evacuees in the United Kingdom.

Special lapel badges were made to help islanders recognize other evacuees.

In London, 20 Upper Grosvenor Street was a contact point for islanders. It offered legal help and kept records for 30,000 Channel Islanders. A room called Le Coin became a "home away from home" for anyone passing through the capital who wanted to meet other Islanders.

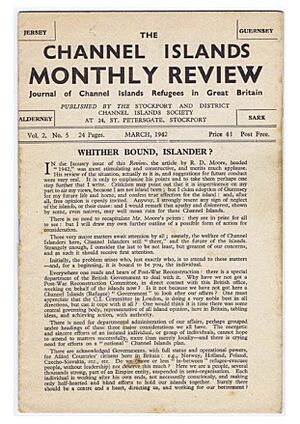

Monthly Review

The Stockport and District Society started in January 1941, with 250 people attending the first meeting. They decided to publish the Channel Island Monthly Review, even though new magazines were banned in August 1940 due to paper shortages. The first four-page edition came out in May 1941. It quickly became popular with thousands of Channel Island people living in the UK. The Review was almost shut down in May 1942 after questions were raised in Parliament.

It didn't close. The 20-24 page Review was published with up to 5,000 copies a month, sent to subscribers, including servicepeople all over the world.

The Review included articles and poetry for Channel Island people. It also shared personal comments from Red Cross messages that might affect other islanders, such as births, marriages, deaths, and greeting messages.

After the Deportations from the German-occupied Channel Islands in September 1942, the December edition of the Review published lists of the deported people and their contact details so Red Cross messages could be sent to them.

Support for Islanders

The Methodist church tried to keep track of its island members in England. They introduced them to English Methodists and provided advice, some money, winter clothing, and help finding jobs.

Many Islanders had moved to Canada over the years and came together to help their homeland evacuees. Philippe William Luce founded the Vancouver Society for the 500 Channel Islanders living there. They collected thousands of dollars and hundreds of crates of clothing and shoes to send to Great Britain.

A "Foster Parent Plan for Children Affected by War" was created in 1937 to help children in the Spanish Civil War. Americans could "adopt" a child and provide money for their education and clothing. Famous people, including film stars, participated. Eleanor Roosevelt adopted three children in 1942. One, Paulette, was a Guernsey evacuee who called her "Auntie Eleanor who lived in the White House".

The BBC recorded island children singing for a Christmas 1942 radio broadcast. The BBC also made a film of the evacuees showing a gathering on June 19, 1943, at the Belle Vue Stadium in Manchester. Six thousand islanders attended.

The British government opened an evacuation account for Guernsey and Jersey. Certain costs, like evacuation ships, train travel, and children's education, could be charged to these accounts. There were concerns about helping Channel Island private schools with their costs, as British private schools received no help when evacuated from cities.

Service and Lives Lost

More than 10,000 islanders who had left the Channel Islands in 1939 or 1940 served with the Allied forces.

| Island | Population in 1931 |

Serving in armed forces |

Percentage serving |

Died whilst serving |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50,500 | 5,978 | 11.8% | 516 | |

| 40,600 | 4,011 | 9.8% | 252 | |

| 1,500 | 204 | 13.6% | 25 | |

| 600 | 27 | 4.5% | 1 | |

| Channel Islands | 93,200 | 10,220 | 10.9% | 794 |

| 44,937,000 | 3,500,000 | 7.3% | 383,700 |

A higher percentage of people from the islands died while serving, compared to their population before the war, than in the United Kingdom.

Also, a higher percentage of civilians who stayed on the islands died, compared to their population before the war, than in the United Kingdom.

Coming Home

People started returning in July and August 1945. Some children came back with northern accents they had picked up.

Children who hadn't seen their parents for five years often didn't recognize them. The adults who had stayed on the islands looked old, tired, thin, and wore old clothes. A few children never got used to being back, as the pain of separation was too great.

For British foster parents, the pain of losing the children they had cared for and loved could be just as bad. Some children and families stayed in touch. Many had fond memories and were very grateful to the northern people who showed so much kindness. The Mayor of Bolton joked that he would threaten the islands with another "invasion" after liberation, because so many holidaymakers from Lancashire would want to see the islands they had heard so much about.

Not all evacuees returned. Families who didn't own property on the islands had found jobs and houses elsewhere. Some young people had found work and love in their evacuation towns. Some who returned found that the men they had left on the islands had started relationships with other women. The same happened the other way around, with women finding new partners. Women who had gotten used to working found no jobs available on the islands except for cleaning floors.

Many adults returned at the same time as the schoolchildren, but some who had volunteered for the armed services were released from duty in 1946. Family reunions could also be difficult, with wives and husbands meeting again for the first time in five years. They discovered they had lived very different lives and found it hard to talk about them. Those who had been evacuated were sometimes told that life was tougher on the islands. Alderney residents were not allowed to return to their island until December 1945.

The islands ended the war with a debt of £9,000,000. This was roughly the total value of every house in the Channel Islands and included the evacuation costs. The British government hoped it would be repaid. However, a generous gift of £3,300,000 from the British government was used to pay back islanders who had lost things. The cost of looking after the evacuees, estimated at £1,000,000, was also written off by the British government.

See also

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |