Coal breaker facts for kids

A coal breaker was a special building or plant that helped prepare coal for use. Its main job was to break large chunks of coal into smaller, more useful sizes. It also cleaned the coal by removing unwanted stuff like slate (a type of rock). The leftover waste was piled up in a place called a culm dump. Think of a coal breaker as an early version of today's modern coal preparation plant.

Coal breakers were mostly used in the United States, especially in Pennsylvania. This state had a lot of a special type of coal called anthracite. While other coal processing places called "coal tipples" were used for different types of coal, coal breakers were always needed for anthracite. This was because anthracite coal needed to be sorted very carefully by size to burn well.

Contents

What a Coal Breaker Did

The first big job of a coal breaker was to break coal into different sizes. This process was simply called "breaking." After breaking, the coal was sorted into groups of similar sizes.

The second important job was to clean the coal. Raw coal often had impurities like slate or rock mixed in. The breaker would remove these unwanted bits. Then, the coal was graded based on how clean it was.

Sorting by size was super important for anthracite coal. For this coal to burn well and efficiently, air needed to flow evenly around each piece. That's why most anthracite coal was sold in uniform sizes. In the early 1900s, coal was sold in several common sizes, from large "Steam" coal (about 4.5 to 6 inches) used for ships, down to very small "Pea" coal (about 0.5 to 0.625 inches) and even smaller "Buckwheat" sizes.

Any coal pieces smaller than about 3/32 of an inch were too tiny to clean properly. These were called "culm" and were considered useless. The cleanest coal had only about 5% impurities, while smaller sizes like "Pea" coal could have up to 15% impurities.

Getting Coal Ready for the Breaker

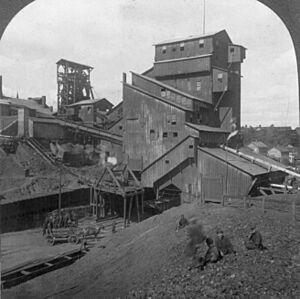

Coal breakers were usually built very close to the mine entrance. This helped to avoid moving the coal too far before it was processed. Before coal entered the breaker, it often went through a "coal tipple." Here, it was crushed and roughly sorted. If water was available, the coal might also be washed.

As coal came out of the mine, it was screened in the tipple. Smaller pieces could go straight to the washer or breaker. Larger chunks were crushed, sometimes many times, until they were small enough to pass through the screen.

Raw coal often contains impurities like slate, sulphur, ash, clay, or dirt. These need to be cleaned out before the coal is sold. Workers would check the coal to decide if it needed washing. Impurities like slate and sulphur are heavier than coal. This means they sink in water that is being stirred. Washing coal worked best if all the lumps were about the same size. If coal was washed, it would enter the breaker "wet." This meant that the slopes of the conveyor belts inside the breaker had to be made less steep so the wet coal wouldn't slide too fast.

History and Technology of Coal Breakers

Before the 1830s, coal wasn't processed much. Miners would use a sledgehammer to break large lumps. Then, they used a rake to collect the bigger pieces. Smaller pieces were left behind because they couldn't be sold.

Around 1830, people started processing coal above ground. Large lumps were placed on metal plates with holes. Workers called "breakers" would hammer the coal until it was small enough to fall through the holes. The coal then fell onto a second screen, which was shaken to sort the smaller lumps. This "broken and screened" coal was worth much more.

Anthracite coal became popular in the 1820s. People in the U.S. found that if anthracite lumps were all about the same size, and air could flow around them, the coal would burn hotter and cleaner. This led to the search for better ways to process it.

The modern coal breaker was invented in 1844 by Joseph Battin in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His invention used two large iron rollers to crush the coal. The crushed coal then rolled down a chute and through a spinning screen. This screen had different sized holes to sort the coal. Heavier impurities tended to fall out at the end of the screen. The sorted coal was collected in bins. The first commercial coal breaker using this idea was built in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, in 1844.

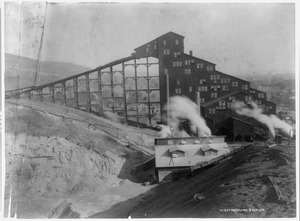

Over time, coal breakers became larger and more complex. By 1866, they looked more like the multi-story buildings we see in old photos. They had many screens and mechanical sorting machines. Steam-powered shaking screens were used in the U.S. by 1890, and steam-powered coal washers by 1892.

Breaker Boys

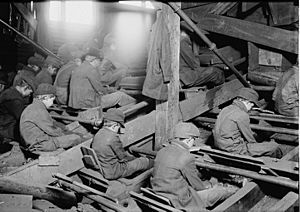

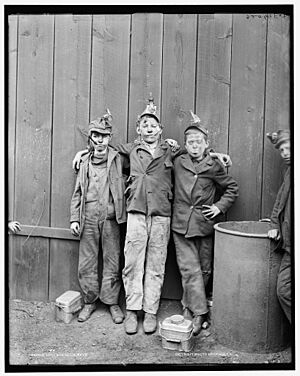

For many years, until about 1900, most anthracite coal breakers relied on people to remove impurities by hand. These workers were usually boys between 8 and 12 years old, known as breaker boys. They started working in the U.S. around 1866.

Breaker boys would sit on wooden seats above chutes and conveyor belts. Their job was to pick out slate and other impurities from the moving coal. They worked long hours, often 10 hours a day, six days a week. It was very dangerous work. The boys couldn't wear gloves because they needed to feel the slick coal. But the slate was sharp, often cutting their fingers. Many boys were seriously hurt or even killed by the fast-moving machinery if they fell into the gears.

The "dry" coal created a lot of dust. This dust was so thick that breaker boys sometimes wore lamps on their heads just to see. Because of the dust, many boys suffered from breathing problems like asthma and a serious lung disease called black lung disease.

People became very upset about children working in such dangerous conditions. In 1885, Pennsylvania passed a law saying no one under 12 could work in a coal breaker. However, this law was not always followed, and some families and employers would fake birth certificates so children could still work. Historians believe that tens of thousands of breaker boys worked in Pennsylvania's coal fields.

New technologies in the 1890s and early 1900s, like mechanical and water separators, helped to remove impurities from coal without needing so many people. This slowly reduced the need for breaker boys. By the 1910s, their numbers were finally dropping due to these new machines, stricter child labor laws, and laws requiring children to go to school. The practice of employing children in coal breakers mostly ended by 1920. This was thanks to groups like the National Child Labor Committee and people like photographer Lewis Hine, who showed the public how bad the conditions were.

Safety Regulations

Safety rules for coal breakers were slow to come in the United States. In the United Kingdom, a law in the mid-1800s required coal breakers to be built away from mine entrances. But in the U.S., laws were only passed after serious accidents.

Two big disasters led to new laws. On September 6, 1869, a small explosion at the Avondale mine in Plymouth, Pennsylvania, caused flames to shoot up the mine shaft. The wooden breaker built right over the mine opening caught fire and collapsed. This trapped and killed 110 workers below. No laws were changed right away.

But in 1871, another fire destroyed a wooden breaker over a mine opening in West Pittston, Pennsylvania, killing 24 miners. After this, even though the coal industry was against it, Pennsylvania passed a law in 1885. This law required coal breakers to be at least 200 feet away from any mine opening.

New Ways to Sort Coal

Many new inventions in the late 1800s and early 1900s helped machines separate impurities from coal.

For dry coal, screens and sorters were used:

- Sorting bars: These were iron bars set at a slope. They were close together at the start and got wider apart. Coal would slide down, and different sized lumps would fall through at different points. Heavier impurities like slate would slide off the end.

- Oscillating bars: Sometimes, these bars moved back and forth. This helped move the coal along and shake off dirt.

- Slate pickers: The "Houser slate picker," invented in 1893, used a bumpy metal plate to make flat pieces of slate stand upright. These upright slate pieces would then get caught by horizontal bars, while the coal passed underneath.

- Gravity separators: An example is the "Herring separator." This was a sloped chute with a rough surface and a hole at the end. Heavier impurities would slow down on the rough surface and fall through the hole, while lighter coal would keep enough speed to pass over the hole.

For wet coal, machines called "coal jigs" were used. These jigs separated coal from impurities using gravity and water. Since coal, slate, and dirt have different weights, they would sink through water at different speeds, allowing them to be separated.

Some examples of coal jigs from the early 1900s include:

- The "Luhrig jig" or "piston jig": This jig pushed water down through a screen. Lighter coal would float to the top, while heavier impurities sank. A conveyor belt would then scoop the coal off the top.

- The moveable pan or "Stewart jig": This jig used a moving perforated plate inside a large tub. The plate's movement created upward water pressure. Lighter coal was pushed to the top and scooped away, while heavier slate stayed at the bottom.

- Sluice boxes: These were used for small pieces of coal. They had low ridges (riffles) that would catch heavier impurities while the lighter coal moved on with the water.

Over time, coal processing continued to improve. By the mid-1900s, new methods like "dense-media separators" were used. These added a very heavy liquid (like one containing magnetite) to the coal and water mixture. The heavy liquid would sink, pushing the lighter coal to the top for collection.

Moving to Coal Preparation Plants

As time went on, new ways to dry coal, like using forced air or heat, were adopted. Coal breakers also started being built with strong materials like steel or reinforced concrete instead of wood, especially as they handled more coal.

After World War II, the demand for coal changed. Many coal breakers were closed or combined into larger facilities. These new, bigger plants were called "coal preparation plants." They could process coal from several mines and often used automation, meaning fewer people were needed to run them. By the 1970s, many old coal breakers were replaced by these newer, larger plants.

How a Coal Breaker Worked

Ideally, coal breakers were built at the same height as, or slightly below, the mine entrance. This way, gravity could help move the coal into the plant. If not, the coal had to be hoisted to the top. A boiler house would provide power for the hoists, screens, and crushers. Coal breakers were often very tall, sometimes 150 feet high or more.

In a typical coal breaker from the early 1900s, coal entered at the very top floor. It would slide down a gently sloped "picker table." Here, breaker boys would pick out obvious impurities like large rocks and slate, throwing them down chutes to the culm pile. They would also send clean lumps of coal down a separate chute for crushing. Coal mixed with impurities went down a third chute for more cleaning.

On the second level, coal was roughly sorted. It moved over sorting bars, sending different sizes down different chutes. Each type of coal then passed over a "slate-picker screen." Round coal would fall through, while flat slate passed over and went to the culm pile. The coal that passed through was then sorted by more screens. Some screens were flat and shaken back and forth, cleaning the coal and breaking larger lumps. Others were cylindrical and rotated, doing the same job.

The third level down was for crushing. Most coal was still in large lumps and needed to be broken into smaller, more marketable sizes. Here, a series of interlocking, toothed crushers or rollers would break the coal into smaller and smaller pieces.

On the fourth level, the coal was cleaned even more. This was originally done by hand, but after 1910, improved screens and jigs took over. While breaker boys worked on all levels, most of the hand-picking happened here. This level also had most of the dry screens and wet jigs. Conveyor belts were used here to move the smaller coal sizes.

Finally, the cleaned coal and culm (waste) reached the ground level. Dry culm was carried away by conveyor belts or rail cars to a nearby dump. Very fine dry culm was sometimes blown through tubes to a separate pile. Wet culm was held in settling tanks to let the dirt settle out of the water. The clean coal, already sorted by size, was loaded onto rail cars and sent to market.

See also

- Huber Breaker

- St. Nicholas coal breakers

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |