Confederate Gulch and Diamond City facts for kids

Confederate Gulch is a deep valley in Montana, on the side of the Big Belt Mountains. A small stream from the gulch flows into Canyon Ferry Lake, which is part of the Missouri River. This area is near the town of Townsend, Montana.

In 1864, during the American Civil War, some Confederate soldiers were released from prison on parole (meaning they promised not to fight anymore). They found a small amount of gold here. But the real excitement began in 1865 with the discovery of the "Montana Bar." This was one of the richest placer gold finds ever!

This amazing discovery led to many more rich gold finds all over Confederate Gulch. It started a huge gold rush that lasted until 1869. From 1866 to 1869, Confederate Gulch produced more gold than any other mining area in Montana Territory. It's estimated that $19 to $30 million worth of gold was found (in money from the 1860s).

For a while, Confederate Gulch was the biggest community in Montana. In 1866, Montana had about 28,000 people. Around 10,000 of them (35%) were working in Confederate Gulch!

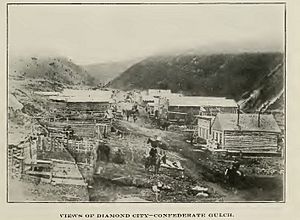

The main town for the miners was Diamond City (46°35′50″N 111°25′26″W / 46.59722°N 111.42389°W). When gold mining was at its peak, Diamond City was the county seat for Meagher County. Today, this area is part of Broadwater County. Diamond City was a very busy place, day and night.

Miners worked hard to get more gold. They built long ditches and flumes (water channels) that stretched for miles. They also used a powerful method called hydraulic mining. This involved using strong jets of water to wash away whole hillsides and the valley floor. This process left huge piles of dirt and rocks called spoil banks. Eventually, hydraulic mining even washed away the original site of Diamond City, so the town had to move!

By 1870, most of the gold in Confederate Gulch was gone. The gold rush was over, and people started to leave Diamond City. In 1870, only 255 people remained. A year later, there were only about 60. Today, you can hardly find any signs of Diamond City or the other towns in the gulch.

An old, unpaved road still goes up the gulch from the Missouri River valley. It crosses the Big Belt Mountains and goes down to the Smith River valley. Confederate Gulch, Diamond City, and the Montana Bar are great examples of Montana's gold mining history. They show how quickly "boom-and-bust" gold camps appeared and disappeared in the late 1800s.

Contents

Geology and Gold

Confederate Gulch is known as its own special mining area. It includes the main gulch and smaller streams like Boulder Creek, Montana Gulch, and Cement Gulch.

The gold found here was mostly in ancient riverbeds and gravels. Scientists found bones of mastodons and elephants in these gravels. This shows that the gold was deposited relatively recently, during the Ice Age. Most of the gold in Confederate Gulch likely came from quartz veins (cracks in rocks with gold inside) on Miller Mountain. Over time, erosion wore down these gold-rich rocks, and the gold settled into the gravels of the gulch.

First Gold Discovery

In 1864 and 1865, before the American Civil War ended, some Confederate soldiers came to Montana Territory to look for gold. Many of them had been part of General Sterling Price's army. After some defeats, the Union (Northern) army commander, General Alfred Pleasonton, offered them a deal. If they promised not to fight anymore (parole) and left the war zone to go west up the Missouri River, they would be released.

This offer seemed like a good choice for many soldiers. Plus, there were rumors of rich new gold discoveries in Montana. So, many of these Confederate soldiers headed to Montana.

In 1864, two Confederate prisoners, Wash Barker and Pomp Dennis, were released in Liberty, Missouri. They got on a steamboat heading up the Missouri River to the Montana goldfields. Steamboats needed wood for their engines, but Native American tribes controlled most of the land along the river. So, the steamboats had to stop often to cut wood. Barker and Dennis worked their way to Montana by chopping wood.

The river was low in 1864, so Barker and Dennis only made it to Cow Island. They had to walk the rest of the way to Fort Benton. News had spread about a new gold strike at Last Chance Gulch (which is now Helena, Montana). But by the time Barker and Dennis arrived, all the good land was taken, and jobs were hard to find.

They saw smoke from other prospectors' camps along the foothills. So, Barker and Dennis started walking up the Missouri River from Last Chance Gulch, looking for gold and living off the land. The Missouri River here was a big, clear mountain river, surrounded by tall mountains. They found small amounts of gold in the gravels, but no big strikes yet.

Later, Jack Thompson and John Wells, who were also former Confederate soldiers, joined them. They eventually found a gulch on the west side of the Big Belt Mountains. It was getting late in the fall, so they decided to stay for the winter. There was a good creek and plenty of wild animals to hunt.

Near the mouth of the gulch, Thompson dug a hole and found the first good gold. It was a piece about the size of a grain of wheat. As they prospected further up the canyon, they found more small amounts of gold. They eventually found enough placer gold in the creek's gravels that a day's hard work could earn them enough to buy some food.

Naming Confederate Gulch and Diamond City

The first gold find by Barker, Dennis, and Thompson was small. But they worked hard and found enough gold that word started to spread. Other people who supported the South arrived in late 1864, and the area became known as Confederate Gulch.

During the winter of 1864–1865, four log cabins were built. They were placed in a perfect diamond shape around a large rock in the narrow valley. From the slopes above, the paths between the cabins looked like a diamond in the snow. So, the cabins were named Diamond City. The "city" part of the name was a bit of a joke, comparing their small settlement to the much bigger, booming mining towns like Helena and Virginia City.

Discovery of the Montana Bar

Diamond City and the nearby mining camp grew slowly at first. In the winter and spring of 1865, many prospectors passed through Confederate Gulch. It was on one of the few trails that went from the Missouri Valley over the Big Belt Mountains to the Smith River Valley. That area had lots of game and good land for farming.

In late 1865, a new group of miners arrived, often called "The Germans." They were led by an experienced miner from Colorado named Carl Joseph Friedrichs (1831–1916). He liked the look of the area and prospected up a stream that later became known as Cement Gulch. This area later became very rich, but the Germans didn't dig deep enough at first, so they decided to move on.

Friedrichs led his group back down the main gulch. He dug a hole in a clear spot on a shelf above the gulch floor, near a small side stream. In that hole, they found an incredible amount of gold! The small side stream became famous as Montana Gulch, and the shelf became even more famous as the Montana Bar of Montana Gulch.

The Montana Bar was only about 2 to 3 acres in size, but it was one of the most amazing placer gold discoveries ever, based on how much gold was found per area. It was also unusual because the gold wasn't at the very bottom of the gulch. Instead, it was on a shelf of gravel higher up on the side of the gulch.

The gravels of the Montana Bar were full of gold from the surface all the way down to the bedrock (the solid rock underneath). The bedrock was a dense, blue-gray limestone. Dips in the bedrock trapped the gold. When water washed over these areas, the gold was so thick you could see it shining from a distance! The gold-rich gravel was about 8 feet deep in most places, but it got thicker, up to 30 or 40 feet, against the mountain.

The few acres of the Montana Bar were unbelievably rich. People claimed that the gravels of the Montana Bar were some of the richest ever found anywhere in the world. It wasn't unusual to find $1,000 worth of gold in just one pan of gravel and dirt. This was when gold was worth less than $20 an ounce! The most gold ever found in one pan, according to witnesses, was $1,400. That's about seven pounds of gold in just two shovelfuls of gravel!

When they first cleaned out the sluice boxes (long wooden channels used to separate gold) on the Bar, the riffles (grooves that catch gold) were completely packed with gold. In just one week, the Montana Bar produced $115,000 worth of gold.

A popular story grew about how the Montana Bar was discovered. The legend says that "The Germans" were new to gold mining and didn't know that gold, being heavier, usually sinks to the lowest parts of a gulch. They kept asking the more experienced Confederate miners for directions to "the good claims." The Confederates, perhaps a bit annoyed, just waved their hands at the hillsides and said, "Go up yonder." According to the story, the Germans simply went "up yonder" and found the Montana Bar!

Gold Production

The discovery of the Montana Bar immediately caused a frenzy of gold searching all over Confederate Gulch and its smaller streams. This quickly led to many more gold finds.

Rich gold deposits were found along Confederate Gulch itself. Two miles up Confederate Gulch, claims in Cement Gulch also proved to be very rich. New discoveries were made up Montana Gulch. Good placer deposits were also found along Greenhorn Gulch and Boulder Gulch.

The Montana Bar discovery made prospectors look at the sides of the gulch, not just the bottom. Gold is heavy, and usually, water and glaciers cause it to settle at the bottom of a valley. But Confederate Gulch was different. Some of the richest gold was found in gravel shelves along the hillsides.

On the same hillside level as the Montana Bar, the Diamond Bar was discovered. It was just as rich per acre as the Montana Bar, though not as large. Gold Hill and other gravel shelves at the same level along the gulch also produced a lot of gold.

The Boulder Bars were in Boulder Gulch. These were shelves of gravel resting on bedrock. They had a special problem: their surfaces were covered with large boulders. Even though there was good gold underneath, the boulders made it very hard to work. As lighter gravel was removed, the boulders would just settle into piles.

Within a few months after the Montana Bar discovery in 1865, Confederate Gulch was buzzing with activity. Gold miners swarmed everywhere, digging and working on their claims.

Gold Production, 1866–1869

For a few years, Confederate Gulch boomed! From 1866 to 1869, Confederate Gulch probably produced as much or more gold than any other camp in Montana. This was because the gold was large and easy to get, water was nearby, and the slopes were good for creating water currents for sluices and for dumping waste. These conditions also allowed miners to switch from simple placer mining to more efficient hydraulic mining.

The first discovery on Montana Bar set records for gold production. The best claims, which were 200 feet wide along the shelf, yielded $180,000. That's about $900 for every foot of width! The Montana Bar alone is estimated to have produced $1 million to $1.5 million in total.

Confederate Gulch itself was mined for about five miles (8 km). When worked properly, the claims along Confederate Gulch were all very rich. The richest parts at the bottom of the gulch were incredibly productive. They produced $100 to $500 per running foot, and $20,000 to $100,000 per claim.

Cement Gulch and Montana Gulch were also very productive. Some claims in Cement Gulch were true "bonanzas" (very rich finds). They produced more gold than similar claims on the famous Montana Bar, even though they required moving much more gravel, boulders, and dirt.

No one knows exactly how much gold was taken from the Boulder Bars. Because of the many boulders on their surface, they were worked by many different miners. Some were just "pocket hunters" looking for small amounts, while others worked with teams of men and equipment.

The gold from Confederate Gulch led to huge gold shipments. A single shipment in 1866, from a short period of running gold-bearing gravel through sluice boxes, weighed two tons and was worth $900,000! In the late 1860s, two and a half tons of gold were produced in one final clean-up of the sluice boxes.

In September 1866, the steamboat Luella, led by Captain Grant Marsh, took 230 miners back down the Missouri River. Between the gold carried by individual miners and the larger shipments, the Luella had two and a half tons of gold on board. This was valued at $1,250,000. This was the richest cargo ever carried down the Missouri River by steamboat! Most of this gold came from the Confederate Gulch area in 1866.

There are different guesses for the total gold production from the Confederate Gulch Mining District during its boom years (1866 to 1869). Estimates range from $16 million to $30 million. These numbers might be much lower than the actual total gold found. The true total will never be known because businesses and individual miners often transported their gold secretly to avoid robbers.

All these gold production estimates are in 1860s dollars. Also, gold was worth less than $20 an ounce back then. If these values were stated in today's money, the figures would be much, much higher.

Confederate Gulch saw a sudden jump in gold production in 1866, which continued strongly through 1867 and 1868, then ended abruptly in 1869/70. Production started high in 1866 because of the incredible richness of the Montana Bar. It stayed high as many new discoveries were made. The intense use of hydraulic mining also kept production levels high until the gold ran out in 1869/70.

Mining Challenges

Along Confederate Gulch and Cement Gulch, the gold claims were rich but required a lot of hard work. Large boulders were mixed with gravel at the bottom of the gulches and had to be moved. Cold water would flood the shafts and trenches. The hillside shelves, like Montana Bar and Diamond Bar, were easier to mine. But even some of these had challenges. On the Boulder Bars, the large boulders on the surface had to be drilled and blasted, or lifted with ropes. These were dangerous jobs.

Hydraulic Mining

Confederate Gulch was a place where large-scale hydraulic mining was used. This method uses the power of water to wash down banks of gravel and terraces on the sides of the gulches, as well as the gravel beds on the gulch floor. The dirt and fine gravel were then flushed through sluice boxes, where the heavier gold was separated from the lighter gravel.

Hydraulic mining worked especially well in Confederate Gulch because the gold-bearing gravels were on terraces high up on the hillsides. Also, there were good water sources and slopes that supported this type of mining.

Water from high up the gulch was collected and sent into flumes or ditches that ran along the sides of the gulch. These channels were built with a much gentler slope than the gulch floor. This meant the water in the flumes eventually became high above the mining sites down on the gulch floor. The water was then released from the high ditch through hundreds of feet of pipe. It came out through huge nozzles that looked like small cannons. The powerful jets of water from these nozzles were so strong they could supposedly smash down a brick building in one pass! The most powerful hydraulic hoses needed six men to control them.

Building the ditches and flumes for hydraulic mining cost a lot of money. This brought outside investors into the gold mining business. They wanted to get their money back as quickly as possible, so they encouraged using hydraulic methods without limits.

The powerful water jets used in hydraulic mining washed away whole hillsides and simply ate up the floor of the gulch. The dirt and fine gravel were washed through the sluices, and the silt was carried away down the gulch. The gravel waste (tailings) from hydraulic mining was left behind as huge piles called spoil banks, stacked along the bottom of the gulch. Hydraulic mining and these spoil banks destroyed all signs of the original Diamond City and other small communities in the gulches. Hydraulic mining caused a lot of damage to the environment in the gulch. It changed the look, geography, and natural environment of Confederate Gulch.

Later Mining Operations

From 1866 to 1869, miners swarmed over the Confederate Gulch area and took almost all the gold. After that, no later mining operations, whether placer or lode mining, came close to the production of the boom years.

After 1870, some hydraulic mining continued off and on in Confederate Gulch for many years. A company from Milwaukee briefly worked some old ground in 1899. About nine years later, a company used a dredge (a machine that scoops up gravel from water) in the lower part of the gulch. But it stopped after three months because it didn't find much gold. Placer mining continued sometimes during the late 1910s and 1920s. Lack of water often made it difficult to succeed.

Gold mining activity often changes with the economy. In the prosperous 1920s, mining slowed down. But as a worldwide economic depression began after 1928, gold production increased. The government set the price of gold higher, to about $35 per ounce. This higher price, combined with lower wages and material costs during the Depression, made gold mining attractive again.

Dredging companies moved into Confederate Gulch in a big way in the 1930s. They used power shovels and other equipment, including a stationary washing plant and different types of dredges. The best results came in 1939 when two dredging operations recovered 2,357 ounces of gold. One company had 16 to 18 workers that season. A single dredge worked the ground in 1942, after which operations stopped for World War II.

The 1939 production of 2,357 ounces of gold was worth $82,495 at the price of $35 per ounce. This is a very small amount compared to the boom days of 1866 to 1869, when tons of gold were produced yearly from Confederate Gulch. Remember, one week on the legendary Montana Bar alone produced $115,000 worth of gold when it was valued at under $20 per ounce!

Lode Mining

Even before the placer gold (gold found in gravels) started to run out, miners were searching the Big Belt Mountains for the "mother lode." This is the main source of gold in solid rock that, through erosion, created all the placer gold found in Confederate Gulch. However, no rich "mother lode" was ever found here. The general idea is that the original source of gold was completely worn away by erosion, and its gold was spread into the gravels along the sides and bottom of Confederate Gulch and nearby valleys.

Although no big mother lode was found, there were some lode mining operations (mining gold from solid rock) in the Confederate Gulch district. But they never produced as much gold as the rich placer mines. The most important lode mines, like the Hummingbird and Three Sisters, are located on Miller Mountain, between Confederate Gulch and White Creek. Lode mines produced only about $100,000 in gold. The placer mines of Confederate Gulch produced that amount 150 times over! A mill called the Philadelphia Mill, which could process 15 tons of rock per day, operated briefly at Diamond City around 1889.

Diamond City: A Famous Boomtown

Confederate Gulch and Diamond City were completely changed by the discovery of the amazing Montana Bar, and then the almost equally impressive Diamond Bar. Gold was being found and shipped in record amounts. News spread quickly across the territory, and miners rushed to the area.

From a small group of cabins and shacks, Diamond City instantly became a crowded boomtown that was busy day and night. Smaller communities also popped up in the Gulch, like El Dorado, Boulder, Jim Town, and Cement Gulch City. At the peak of the gold rush, ten thousand people lived and worked in Confederate Gulch. Diamond City was the most important town, and when Meagher County was formed, Diamond City was named the county seat.

Between 1866 and 1869, when Diamond City and Confederate Gulch had ten thousand people digging for gold, the federal government estimated Montana's total population at 28,000. During these years, about 35% of Montana's population was working in Confederate Gulch!

Placer gold discoveries, like Confederate Gulch, attracted many different kinds of people. Many came from the Midwest and border states like Missouri. Many also came from mining areas in California, Idaho, and Nevada. Because these miners moved around so much, they didn't care much about a person's background. People often used casual nicknames instead of proper names. A list of Confederate Gulch citizens might include names like Wild Goose Bill, Black Jack, Nubbins, Roachy, Steady Tom, Workhorse George, Dirty Mary, and Lonesome Larry.

Placer gold finds were often called "poor man's diggings." Placer gold forms when erosion slowly breaks down gold veins in solid rock. Over long periods, the gold settles into the gravels and sands of old or current riverbeds. The gold is found in its natural form, as dust, flakes, or nuggets. These deposits didn't need special processing, just hard, tiring work to dig out and sort through tons of gravel, dirt, sand, and boulders. New discoveries like Confederate Gulch attracted young men who wanted to get rich quickly.

Towns that grew up around placer gold strikes were quickly built, temporary, and very busy places. Diamond City and the other Confederate Gulch communities were no different. As long as gold was being produced, they boomed. When the mining stopped, the prospectors left as quickly as they came.

During the boom years, Diamond City was full of excitement and activity. It offered entertainment and goods for the miners and for the crews who worked day and night to build a 7-mile-long (11 km) ditch and flume for hydraulic mining. When this system was finished, full-scale hydraulic mining began. At the height of mining activity, between 1866 and 1869, hydraulic mining caused Diamond City to be moved. The approaching hydraulic mining dug away the ground under the town, and spoil banks (piles of waste) started to build up against buildings. Merchants first propped their buildings on stilts. Eventually, the stilts reached fifteen feet high! Finally, the town was simply moved to a nearby spot in Confederate Gulch, where business continued as usual. Meanwhile, the hydraulic mining process ate its way through the former town site.

Gold production from 1866 through 1869 was intense. The rich deposits encouraged quick mining, and the switch to hydraulic mining kept production very high. This led to record amounts of gold, but it also shortened the life of the community. In 1869 and 1870, the gold ran out, and so did the population. People simply packed up and left. By 1870, the population of Diamond City was down to 225 people. A year later, only about 64 people remained. By the 1880s, only 4 families were left.

From nothing in 1864, and just a few cabins in 1865, Diamond City became the county seat of Meagher County and the center of the most populated mining camp in Montana in 1866. Diamond City boomed for three years until 1869. Then, the party was over. Almost everyone left, and Diamond City disappeared. Unlike other boom-and-bust areas, Diamond City didn't even remain as a picturesque ghost town. The intense search for gold destroyed Diamond City, and hardly a trace remains today. Because of its quick rise and fall, Diamond City has been called "the most spectacular of Montana's boom and bust gold towns."

Confederate Gulch Today

Today, you can drive to and through Confederate Gulch on a road that is usable but not paved. Confederate Gulch is different from other boom-and-bust mining areas in Montana because no ghost town was left behind. The hydraulic mining during the boom years, and later mining that reworked the site, have erased the locations of the old mining communities. Along the bottom of the gulch, you can see spoil banks (piles of waste gravel) that are now overgrown with bushes. Sometimes, you might see pieces of old timber in these areas, showing that towns and buildings once stood in the gulch.

Only one thing truly remains. On a cliff overlooking Confederate Gulch and Boulder Gulch from the south, there is a graveyard for Diamond City and Confederate Gulch. About 65 people are said to be buried there. This site is marked on Wikimapia.

Images for kids

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |