Cormac mac Cuilennáin facts for kids

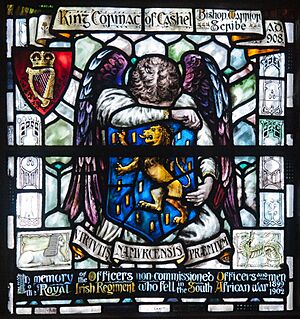

Cormac mac Cuilennáin (died September 13, 908) was an important Irish bishop and king of Munster. He ruled from 902 until he died in a battle called the Battle of Bellaghmoon in Leinster.

After his death, many people thought Cormac was a saint. His shrine in Castledermot, County Kildare, was believed to be a place where miracles happened. He was also known as a great scholar. People say he wrote Sanas Cormaic (Cormac's Glossary) and a book called the Psalter of Cashel, which is now lost. Some stories about Cormac might not be completely true. His special day, or feast day, is September 14.

Ireland in Cormac's Time

During Cormac's life, Ireland was split into many small kingdoms. These were called túatha. There were about 150 of them, each around 500 square kilometers in size. Each túath was supposed to have its own king and bishop.

Larger groups of túatha were controlled by one powerful king. Above these were five big provincial kingdoms. These are the same names we use for the provinces of Ireland today: Connacht, Leinster, Ulster, Meath, and Cormac's own Munster. There were also kings of the northern and southern Uí Néill. These Uí Néill kings were often the High Kings of Ireland, who had a lot of power across the island.

When Cormac was king, Flann Sinna was the High King. Besides these Irish kings, there were also Scandinavian and Norse-Gael kings. They had set up settlements along the coasts during the Viking Age. The Vikings had been weakened, and they were even kicked out of Dublin in the same year Cormac became king of Munster.

Cormac belonged to a smaller part of the Eóganachta family. This family was very powerful in Munster during the 8th and 9th centuries. Cormac was from the Cashel branch of this family. He was a very distant descendant of an important king named Óengus mac Nad Froích. Because he was a bishop and abbot, Cormac was likely chosen as king because he was a good compromise candidate.

Some old writings say that Cormac was taught by Snedgus of Castledermot. Later stories claim Cormac was supposed to marry Gormlaith, the daughter of High King Flann Sinna. But instead, he decided to become a celibate (meaning he would not marry). Historians think these stories might not be true. We know Cormac was a bishop before and during his time as king of Munster, but it's not clear which church area (or see) he was in charge of. Some people think he was linked to Emly rather than Cashel.

King and Bishop

Cormac became king of Munster after the previous king, Finguine Cenn nGécan, was killed. Old records say Finguine was "deceitfully killed by his associates." When Cormac became king, the Annals of Innisfallen (an old Irish record) called him a "noble bishop and celibate."

Cormac might have tried to make the kings of Munster more powerful. He wanted them to have more control over nearby Leinster. He might have even wanted to become the chief king of all Ireland. Records from that time were often written by people from the north of Ireland who supported the Uí Néill family. These records might not fully show how powerful Cormac and the Eóganachta family really were.

However, the southern Annals of Innisfallen do report that Cormac led armies in 907. He went into Connacht and Mide, where he defeated High King Flann Sinna. Cormac also sent a fleet of boats on the River Shannon that captured Clonmacnoise.

Cormac's Final Battle

In 908, Cormac and his main advisor, Flaithbertach mac Inmainén, gathered an army. They planned to fight against their eastern neighbors in Leinster. The king of Leinster, Cerball mac Muirecáin, was High King Flann Sinna's son-in-law and a strong ally.

An old account says that when the Munster army gathered, Flaithbertach mac Inmainén's horse stumbled and threw him off. This was seen as a very bad sign. Many of the Munster soldiers did not want to fight. News of this reached Cerball mac Muirecáin, who suggested they talk and make peace. The Leinstermen would pay tribute (a payment) and give hostages (people held as a promise). But the hostages would go to a trusted abbot, not to the Munstermen.

Cormac was willing to agree to this peace. But Flaithbertach convinced him to fight instead. Cormac himself believed he would be killed in the battle. When the soldiers heard that Flann Sinna and the Uí Néill had come to help Cerball, many of Cormac's soldiers left the army.

Even so, Cormac continued to march into Leinster. He met Cerball and Flann at Bellach Mugna (now Bellaghmoon, in County Kildare). The old records say that "the men of Munster came to the battle weak and in disorder." They quickly broke and ran away. Many were killed, including Cormac. He fell off his horse and broke his neck. Flaithbertach was captured.

Cormac was beheaded, and his head was brought to Flann Sinna. The old writings say Flann was upset by this. He said, "It was an evil deed to cut off the holy bishop's head; I shall honour it, and not crush it." Flann took Cormac's head, kissed it, and carried it around him three times.

After Cormac's death, Munster did not have a king for a few years. Then, Flaithbertach mac Inmainén was chosen as king.

Scholar and Saint

By the 11th century, Cormac was considered a saint. The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland say that Cormac was buried at Castledermot. They also say that "Cormac's body ... produces omens and miracles."

These old writings also praise Cormac's learning and religious devotion. They call him "A scholar in Irish and in Latin, the wholly pious and pure chief bishop, miraculous in chastity and in prayer, a sage in government, in all wisdom, knowledge and science, a sage of poetry and learning, chief of charity and every virtue; a wise man in teaching, high king of the two provinces of all Munster in his time."

Several books are linked to Cormac. One is the Sanas Cormaic, which is a glossary (a list of difficult words with their meanings) of Irish words. It's like a dictionary from his time. While the main part of this book is from around Cormac's era, we are not sure if he actually wrote it himself. The lost Psalter of Cashel and the Lebor na Cert (the Book of Rights) are also connected to Cormac.

See also

In Spanish: Cormac de Cashel para niños

In Spanish: Cormac de Cashel para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |