Desanka Maksimović facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Desanka Maksimović

|

|

|---|---|

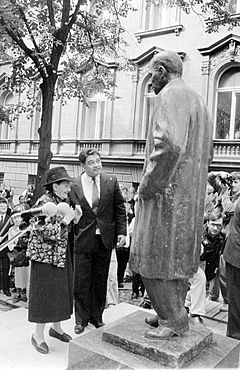

Maksimović in 1975

|

|

| Born | 16 May 1898 Rabrovica, Valjevo, Kingdom of Serbia |

| Died | 11 February 1993 (aged 94) Belgrade, FR Yugoslavia |

| Occupation | Poet, writer, translator |

| Nationality | Serbian |

| Alma mater | University of Belgrade University of Paris |

| Period | 1920–1993 |

| Spouse | Sergej Slastikov (1933–1970) |

Desanka Maksimović (Serbian Cyrillic: Десанка Максимовић; born May 16, 1898 – died February 11, 1993) was a famous Serbian poet, writer, and translator. She started publishing her first poems in a magazine called Misao in 1920. At that time, she was studying at the University of Belgrade. Soon, her poems also appeared in the Serbian Literary Herald, which was a very important literary magazine in Belgrade.

In 1925, Maksimović received a special scholarship from the Government of France to study in Paris for a year. When she came back, she became a professor at a top high school for girls in Belgrade. She taught there until World War II began.

In 1933, Desanka married Sergej Slastikov, a writer from Russia. During the German occupation in 1941, she lost her teaching job. She became very poor and had to do many small jobs to get by. She was only allowed to publish books for children during this time. However, she secretly wrote many patriotic poems. These poems were published after the war. One of her most famous poems from this period is Krvava bajka (A Bloody Tale). It tells the story of schoolchildren killed in the Kragujevac massacre. This poem was often read at ceremonies after the war and became one of the most well-known Serbian poems.

To celebrate her 60th birthday in 1958, Maksimović received many awards. In 1964, she published another famous work called Tražim pomilovanje (I Seek Clemency). This book of poems subtly criticized the government led by Josip Broz Tito, which made it very popular. The next year, she became a full member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. After her husband passed away in 1970, her poems often focused on the idea of life and death. Maksimović traveled a lot in the 1970s and 1980s. Some of her trips inspired new poems. In the early 1980s, she also worked to fight against government censorship. She remained active until her death in 1993.

Desanka Maksimović was the first female Serbian poet to be widely accepted by writers and the public. She showed other Serbian women that they could also become successful writers. Many people knew her simply by her first name, Desanka. One author even called her "the most beloved Serbian poet of the twentieth century."

Biography

Childhood Years

Desanka Maksimović was born in a village called Rabrovica, near Valjevo, on May 16, 1898. She was the oldest of seven children. Her father, Mihailo, was a schoolteacher, and her mother, Draginja, was a housewife. Her family had moved to Serbia from Herzegovina in the late 1700s. Her grandfather on her mother's side was an Orthodox priest.

When Desanka was just two months old, her father got a new job in the nearby village of Brankovina. So, her family moved there. Desanka spent most of her early childhood in Brankovina. She loved reading from a young age and spent many hours in her father's library. When she was 10, her family moved to Valjevo.

World War I brought great sadness to Maksimović's family. In 1915, her father died from typhus while serving in the Royal Serbian Army. His death left the family in a difficult financial situation. To help her mother and siblings, Desanka had to leave high school. In her free time, she learned French. After the war, she went back to school and finished in 1919.

Starting Her Career

After finishing high school, Maksimović moved to Belgrade. This city was the capital of the new country called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. She enrolled at the University of Belgrade. There, she studied art history and comparative literature. By this time, Desanka had already been writing poems for several years. She shared some of her poems with a former professor. This professor then gave them to Velimir Masuka, the editor of Misao (Thought). Misao was one of Serbia's leading art and literature magazines.

Maksimović's poems first appeared in Misao between 1920 and 1921. She won her first literary award when readers of the journal voted one of her poems as the best. A few years later, the Srpski književni glasnik (Serbian Literary Herald) started printing her poems. This was Belgrade's most important literary journal. Several of her works also appeared in a collection of Yugoslav poems.

In 1924, Maksimović published her first book of poems, simply called Pesme (Poems). The book received good reviews. Around this time, she graduated from the University of Belgrade. She also received a scholarship from the Government of France to study in Paris for a year. She returned to Belgrade in 1925. Upon her return, she received a Saint Sava medal from the government for her writing. She also became a professor at the city's top First High School for Girls.

By the late 1920s, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes faced many ethnic tensions. In 1929, King Alexander changed the country's name to Yugoslavia. This was done to try and reduce growing nationalist feelings. Soon, political disagreements also affected literature. Yugoslav writers could not agree on the direction their literature should take. Older writers preferred traditional styles. Younger writers wanted to use modernism to explore modern life and human feelings. Maksimović always stuck to traditional literary forms. This led to strong criticism from many of her fellow writers. She later said, "I would not have had as many friends as I have now if I had not been able to forget the biting jokes or critical remarks about my poetry or myself."

Yugoslavia faced tough economic times during the Great Depression. The country's political situation also got worse. During this period, Maksimović focused mainly on poetry. Many of her poems were first read aloud to other writers at the home of Smilja Đaković, the publisher of Misao. In 1933, Maksimović married Sergej Slastikov, a writer born in Russia.

After the German-led Axis invasion and occupation of Yugoslavia, Maksimović was forced to retire from her teaching job. She became very poor. To earn money, she gave private lessons, sewed children's clothes, and sold dolls. To heat her apartment, she had to walk from downtown Belgrade to Mount Avala to collect firewood. She secretly wrote patriotic poems during this time. However, she was only allowed to publish children's books.

Later Life and Legacy

After the war, Yugoslavia became a socialist state led by Josip Broz Tito. Maksimović got her job back as a professor at the First High School for Girls. In 1946, she published a collection of war poems called Pesnik i zavičaj (The Poet and His Native Land). This collection included one of her most famous poems, Krvava bajka (A Bloody Fairy Tale). This poem was a tribute to the children killed in the Kragujevac massacre in October 1941. Even though she was not a communist, her works were approved by the Yugoslav government.

Maksimović loved Russia very much. Sometimes, her love for Russia was mistaken for being a secret supporter of the Cominform. This was a serious accusation after the Tito–Stalin Split. If proven, it could have led to prison. Maksimović retired from teaching in 1953. In 1958, for her 60th birthday, she received many awards from the Yugoslav government and literary groups. The next year, she became a partial member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU).

In 1964, Maksimović published a book of poems called Tražim pomilovanje (I Seek Clemency). This book explored the 14th-century rule of Dušan the Mighty, who founded the Serbian Empire. The collection was very popular and quickly became a bestseller. Its subtle criticism of Tito's government made it especially liked by those who were unhappy with the government's increasing unfairness and corruption.

Maksimović received more honors in the following years. In 1965, her colleagues voted her a full member of the SANU. By this time, Maksimović was well-known and respected not only in Yugoslavia but also around the world. Her works were translated into many languages. The famous Russian poet Anna Akhmatova was one of her translators. In 1967, Maksimović received a medal from the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union.

Maksimović's husband died in 1970. After his death, her poems increasingly focused on the topic of human life and death. In 1975, she received a Vuk Karadžić Award for Lifetime Achievement from the SANU. She was only the second writer to receive this honor, after Nobel winner Ivo Andrić. The next year, Maksimović published Letopis Perunovih potomaka (A Chronicle of Perun's Descendants). This poetry collection was about medieval Balkan history.

She traveled widely in the 1970s and 1980s. She visited many European countries, including the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom. She also went to Australia, Canada, the United States, and China. Her trips to Norway and Switzerland inspired new works. These included the poetry collection Pesme iz Norveške (Poems from Norway; 1976) and a travel book called Snimci iz Švajcarske (Snapshots from Switzerland; 1978). In 1982, Maksimović helped start the Committee for the Protection of Artistic Freedom. This group worked to end government censorship. In 1988, she published a poetry collection called Pamtiću sve (I Shall Remember Everything). She passed away in Belgrade on February 11, 1993, at the age of 94.

Legacy

"Maksimović... shaped a whole era with her lyrical poetry," writes literary scholar Aida Vidan. She was the first female Serbian poet to be widely accepted by her mostly male colleagues in Yugoslav literature. She was also the first Serbian female poet to become very popular with the general public. She was Yugoslavia's leading female writer for seventy years. She gained this recognition between the two World Wars and kept it until her death. Scholar Dubravka Juraga calls her "the beloved leader of Yugoslav belles lettres" (fine literature).

Maksimović "gave women writers a great example of success in lyric poetry," writes literary scholar Celia Hawkesworth. Hawkesworth compares Maksimović's contributions to Serbian literature to those of other famous female poets in other countries. The author Christopher Deliso describes Maksimović as "the most beloved Serbian poet of the twentieth century." During her lifetime, she was so famous that many people simply called her Desanka. Her poem Krvava bajka is considered one of the best-known Serbian poems. She is also credited with making love locks popular in former Yugoslavia through one of her poems. By the early 2000s, this trend had spread to other parts of the world.

A statue of Maksimović was revealed in Valjevo on October 27, 1990, while she was still alive. In the 1990s, after Yugoslavia broke up, many street names changed. Đuro Salaj Street in Belgrade was renamed Desanka Maksimović Street. In May 1996, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia issued a special postage stamp to honor her. A bronze statue of Maksimović was put up in Belgrade's Tašmajdan Park on August 23, 2007.

Works

- Pesme (Poems; 1924)

- Vrt detinjstvа (Childhood Garden), poems (1927)

- Zeleni vitez (Green Knight), poems (1930)

- Ludilo srcа (Heart's Madness), short stories (1931)

- Srce lutke spаvаljke i druge priče za decu (The Sleeping Doll's Heart and Other Stories for Children; 1931, 1943)

- Gozbа na livаdi (Feast in the Meadow), poems (1932)

- Kаko oni žive (How They Live), short stories (1935)

- Nove pesme (New Poems; 1936)

- Rаspevаne priče (Singing Stories; 1938)

- Zаgonetke lаke za prvаke đаke (Easy Riddles for First Graders; with Jovаnkom Hrvаćаnin; 1942)

- Šаrena torbicа (Colorful Bag), children's poems (1943)

- Oslobođenje Cvete Andrić (The Liberation of Cveta Andrić), poem (1945)

- Pesnik i zavičаj (The Poet and His Native Land), poems (1945)

- Otаdžbina u prvomаjskoj povorci (Homeland in the May Day Parade), poem (1949)

- Sаmoglаsnici A, E, I, O, U (Vowels A, E, I, O, U; 1949)

- Otаdžbino, tu sаm (Homeland, I Am Here; 1951)

- Strаšna igrа (Terrible Game), short stories (1950)

- Vetrovа uspаvаnkа (Wind's Lullaby; 1953)

- Otvoren prozor (Open Window), novel (1954)

- Prolećni sаstаnak (Spring Meeting; 1954)

- Miris zemlje (Scent of Earth), selected poems (1955)

- Bаjkа o Krаtkovečnoj (Tale of the Short-Lived One; 1957)

- Ako je verovаti mojoj bаki (If My Grandmother Is to Be Believed), short stories (1959)

- Zаrobljenik snovа (Prisoner of Dreams; 1960)

- Govori tiho (Speak Quietly), poems (1961)

- Prolećni sаstаnak (Spring Meeting; 1961)

- Pаtuljkovа tаjna (Dwarf's Secret), short stories (1963)

- Ptice na česmi (Birds at the Fountain), poems (1963)

- Trаžim pomilovаnje, lirskа diskusijа s Dušаnovim zakonikom (I Seek Clemency, Lyrical Discussion with Dušan's Code; 1964)

- Hoću dа se rаdujem (I Want to Rejoice), short stories (1965)

- Đаčko srce (Student's Heart; 1966)

- Izvolite na izložbu dece slikаrа (Welcome to the Exhibition of Child Painters; 1966)

- Prаdevojčicа (Pre-Girl), novel (1970)

- Na šesnaesti rođendаn (On the Sixteenth Birthday), poems (1970)

- Prаznici putovаnjа (Holidays of Travel), travel writing (1972)

- Nemаm više vremena (I Have No More Time), poems (1973)

- Letopis Perunovih potomаkа (A Chronicle of Perun's Descendants), poems (1976)

- Pesme iz Norveške (Poems from Norway; 1976)

- Bаjke za decu (Fairy Tales for Children; 1977)

- Snimci iz Švajcarske (Snapshots from Switzerland), travel book (1978)

- Ničijа zemljа (No Man's Land; 1979)

- Vetrovа uspаvаnkа (Wind's Lullaby), children's poems (1983)

- Međаši sećаnjа (Milestones of Memory), poems (1983)

- Slovo o ljubаvi (A Word About Love), poems (1983)

- Pаmtiću sve (I Shall Remember Everything; 1989)

- Nebeski rаzboj (Heavenly Loom; 1991)

- Ozon zavičаjа (Ozone of the Homeland; 1991)

- Zovina svirаlа (Elderberry Flute; 1992)

See also

In Spanish: Desanka Maksimović para niños

In Spanish: Desanka Maksimović para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |