Deskaheh facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Levi General

|

|

|---|---|

| Deskaheh | |

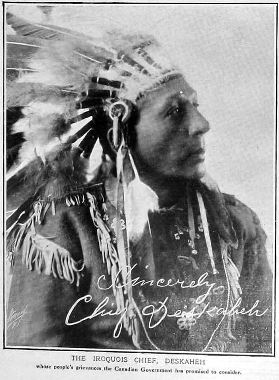

Photograph of Chief Deskaheh appearing in 'The Graphic', 1922

|

|

| Cayuga statesman | |

| In office 1917–1925 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Levi General

March 15, 1873 Tuscarora Township, Ontario |

| Died | June 27, 1925 (aged 52) Tuscarora Reservation, New York |

| Spouse | Mary Bergen |

| Relations | Seven brothers and sisters, including Alex General |

| Children | Four daughters, including Rachel General |

| Parents | |

Levi General (March 15, 1873 – June 27, 1925), known as Deskaheh, was an important leader of the Haudenosaunee people. He was a hereditary chief and a speaker who worked hard to get his people recognized. He is most famous for taking the concerns of the Iroquois to the League of Nations in the 1920s.

Contents

Early Life

Levi General grew up learning the traditions of the Cayuga. He was active in Longhouse ceremonies. He spoke his first language, Cayuga, and other Iroquois languages too.

He worked as a lumberjack in the Allegheny Mountains in New York and Pennsylvania. After an accident, he returned home. He started farming near Ohsweken on the Six Nations Reserve. There, he got married and had four daughters.

Speaker for the Six Nations

In 1917, Levi General became a hereditary chief of the Cayuga. He was given the title "Deskaheh," which means "more than eleven."

Traveling to London

In August 1921, Deskaheh traveled to London with a lawyer named George P. Decker. The Six Nations hired Decker to help them. The Canadian government would not let Deskaheh travel. So, the Six Nations Confederacy gave him their own passport. This was Decker's idea.

In London, Deskaheh appeared at the Hippodrome in his traditional clothing. He also shared a paper called "Petition and Case of the Six Nations of the Grand River." Winston Churchill, who worked for the British government, said the petition should go back to Canada. So, Deskaheh and Decker returned to the United States.

Seeking Support in Washington, D.C.

In 1922, Deskaheh and Decker went to Washington, DC. They got help from the Netherlands' foreign affairs minister, H. A. van Karnebeck. He sent their petition to the League of Nations' main office. They also got support from a Swiss group that helped Indigenous people.

Challenges at Home

In 1923, Canadian officials built Royal Canadian Mounted Police barracks on Six Nations land. They searched private homes. They also stopped Indigenous people from cutting wood for fuel, even though others could. This made the Six Nations want protection from the British crown even more.

Deskaheh went to Rochester, NY. He and Decker planned to ask the League of Nations to take action against Canada.

Speaking in Switzerland

On July 14, 1923, Deskaheh and Decker sailed to Geneva, Switzerland. Decker went back to the U.S. after a short time. But he and Deskaheh stayed in touch by mail.

Deskaheh stayed in Switzerland for 18 months. He gave many speeches to large groups in Geneva, Bern, Lausanne, Lucerne, Winterthur, and Zurich. In his speeches, he reminded European countries of their promises. These promises were made in the Two Row Wampum, an important agreement between the Iroquois and Europeans.

Deskaheh was a great speaker and could speak French. This helped him gain support from some nations. These included Ireland, Panama, Persia, Japan, and Estonia. Historians say that while Swiss people liked his speeches, they did not change the minds of the British or Canadian governments.

Government Changes and Final Efforts

On September 17, 1924, the Governor-General of Canada, Julian Byng, 1st Viscount Byng of Vimy, ordered a change. He said the traditional Six Nations Council at Ohsweken should be replaced by an elected council. This was part of Canada's Indian Act.

On October 7, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police ended the traditional government of the Six Nations. They took important documents and wampums. They also announced an election to replace the traditional leaders. Deskaheh spoke out even more strongly after these events. He even wrote directly to King George V. However, he could not make progress. He was never able to speak to the League of Nations directly. But he left a copy of a statement at their offices in Geneva before he left on January 3, 1925.

Deskaheh spent his last six months in Rochester, New York. He gave speeches, including his most famous one on March 10, 1925. He gave this speech over a local Rochester radio station. In this speech, he talked about policies that tried to force Indigenous people to change their culture. He said:

"In Ottawa, they call that policy 'Indian Advancement.' In Washington, they call it 'Assimilation.' We, who would be the helpless victims, say it is unfair control. If this must continue to the very end, we would rather you come with your weapons and get rid of us that way. Do it openly and clearly."

Death and Legacy

Deskaheh was staying at the home of Chief Clinton Rickard on the Tuscarora Reservation. He was suffering from pneumonia, which followed a bad cold he got in Europe. He asked for his traditional medicine man from the Six Nations Reserve in Canada. But the medicine man was not allowed to cross the border. The U.S. had just passed a law that stopped people who did not speak English from entering.

On his deathbed, Deskaheh told Rickard to "Fight for the line." Chief Rickard later started the Indian Defense League in 1925. This group worked to protect the right of Indigenous people to travel freely across borders.

Deskaheh was buried on June 30 on the Six Nations Reserve. Two thousand people came to mourn him. Modern Iroquois people see Deskaheh as a great patriot.

See also

In Spanish: Deskaheh para niños

In Spanish: Deskaheh para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |