Dimetrodon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids DimetrodonTemporal range: early Permian

295–272 mya |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Dimetrodon grandis skeleton at the National Museum of Natural History |

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: |

†Sphenacodontidae

|

| Genus: |

†Dimetrodon

Cope, 1878

|

Dimetrodon was a fascinating animal that lived a very long time ago. It was a type of early reptile-like creature called a pelycosaur. These animals are also known as synapsids, which are a group that eventually led to mammals. Dimetrodon lived during the first part of the Permian period, about 295 to 272 million years ago.

This creature walked on four legs. It had a tall, curved head with different-sized teeth. Most Dimetrodon fossils have been found in the southwestern United States. These fossils come from red beds in Texas and Oklahoma. The biggest known Dimetrodon species, D. angelensis, was about 4.6 meters (15 feet) long. The smallest, D. teutonis, was only about 60 centimeters (2 feet) long.

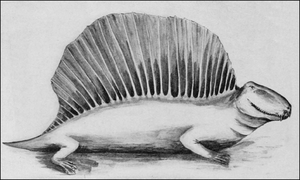

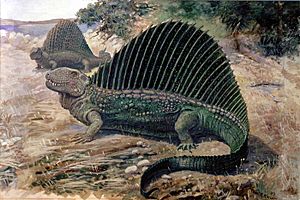

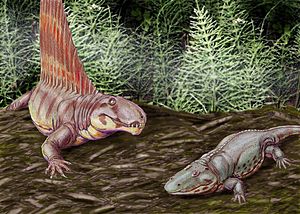

Dimetrodon was a carnivore, meaning it ate meat. It was likely the top predator in its environment. Its most famous feature is the large "sail" on its back. This sail was made of long spines growing from its backbone. These spines were covered with skin. Scientists believe this sail helped Dimetrodon control its body temperature. It could warm up by facing the sun or cool down in the shade. At that time, no land animals could keep a steady body temperature like mammals do today. The sail might also have been used to show off for mates or to mark its territory. If so, the skin on the sail would have been brightly colored. This is just a guess, but it helps explain this amazing feature.

In terms of evolution, Dimetrodon was a synapsid. This group of land animals eventually led to all mammals. Dimetrodon itself wasn't a direct ancestor of mammals. But it was a great example of the types of synapsids that lived during the Permian period.

Contents

What Dimetrodon Looked Like

Dimetrodon was a four-legged synapsid with a sail on its back. Most species were between 1.7 to 4.6 meters (5.6 to 15 feet) long. They probably weighed between 28 and 250 kilograms (62 to 551 pounds). The largest species was D. angelensis, at 4.6 meters (15 feet). The smallest was D. teutonis, at 60 centimeters (2 feet). The bigger Dimetrodon species were among the largest predators of their time. Even though some Dimetrodon grew very big, many young Dimetrodon fossils have also been found.

Its Skull

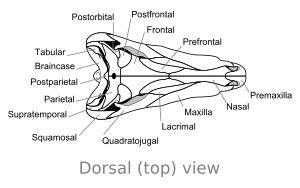

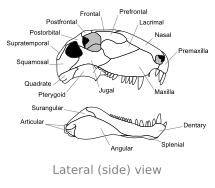

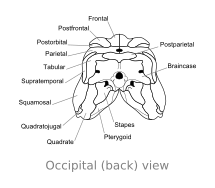

The Dimetrodon skull had a single large opening on each side at the back. This feature connects Dimetrodon to mammals. It also makes it different from most early reptiles, which either had no openings or two. Other features in its skull show how early four-limbed animals slowly changed into mammals.

The skull of Dimetrodon was tall and flat from side to side. Its eye sockets were high up and far back on the head. Behind each eye socket was a single hole called an infratemporal fenestra. Another hole, the supratemporal fenestra, could be seen from above. The back of the skull was angled slightly upward. This is a feature shared with all other early synapsids. The top of the skull curved downward to the tip of the snout. The tip of the upper jaw was raised, creating a "step." In this step, there was a gap in the teeth. Its skull was built more strongly than a dinosaur's.

Its Teeth

The teeth of Dimetrodon were very different in size. This is why its name means "two measures of tooth." It had sets of small and large teeth. One or two pairs of large, pointed, canine-like teeth grew from its upper jaw. Large front teeth were also at the tips of both upper and lower jaws. Smaller teeth were found behind the large ones, getting even smaller towards the back of the jaw.

Many of its teeth were widest in the middle, like a teardrop shape. This teardrop shape is special to Dimetrodon and its close relatives. It helps scientists tell them apart from other early synapsids. Like many early synapsids, most Dimetrodon teeth had tiny saw-like edges called serrations. These serrations were so fine they looked like tiny cracks. A study in 2014 showed that Dimetrodon and its prey were in an "arms race." As prey animals grew larger, Dimetrodon also grew larger. Its teeth became sharper with more specialized serrations to cut through flesh. This shows how Dimetrodon evolved over millions of years to become a better hunter.

Its Nose and Jaw

Inside the nasal part of the skull were ridges. These ridges might have helped Dimetrodon smell better. They are smaller than those in later synapsids. Those later animals might have been warm-blooded. This suggests Dimetrodon's nose was a step between early land animals and mammals.

Another interesting feature was a ridge at the back of its jaw. This ridge was on a bone that connected to the skull to form the jaw joint. In later mammal ancestors, this bone became part of the middle ear. This shows how Dimetrodon was a "transitional fossil." It had features that link early land animals to mammals.

Its Tail

The tail of Dimetrodon was very long. It made up a big part of its total body length. Early fossil discoveries had incomplete tails. This made scientists think Dimetrodon had a short tail. But in 1927, a nearly complete tail was found. This showed that Dimetrodon actually had a very long tail.

Its Sail

The sail on Dimetrodon's back was made of long spines from its backbone. Each spine changed shape from its base to its tip. Near the backbone, the spine was flat and rectangular. Closer to the tip, it looked like a figure-eight. This figure-eight shape helped make the spine strong. It kept the spine from bending or breaking. The lower part of the spine was rough. This is where back muscles would have attached. It also had fibers that show it was inside the body. The outer part of the spine was smoother. It had small grooves for blood vessels that fed the sail.

Scientists once thought a large groove on the spine carried blood vessels. But now they think the sail didn't have as many blood vessels as once believed. Some Dimetrodon fossils show healed breaks on the spines. This suggests that soft tissue must have covered the sail. This tissue would have brought blood to heal the breaks. The bone of the spines also has growth rings. These rings can tell scientists how old the animal was when it died. In some Dimetrodon specimens, the tips of the spines were bent. This means the sail might not have been perfectly smooth. It also suggests the skin might not have covered the very tips of the spines.

Its Skin

No fossil skin of Dimetrodon has been found yet. But a related animal had smooth skin with many glands. Dimetrodon might also have had large scales, called scutes, on its belly and tail. Other synapsids had these.

How Dimetrodon Lived

What the Sail Was For

Scientists have many ideas about what the sail was used for. Some early ideas suggested it was for camouflage in reeds. Or maybe it was like a boat sail to catch the wind in water. Another idea is that the long spines helped keep the body stable. This would have made walking from side to side more efficient.

The most popular idea is that the sail helped control body temperature. Dimetrodon could warm up quickly in the morning sun. It could also cool down by finding shade or changing its position. The sail would have acted like a solar panel. It helped the animal absorb or release heat. This was important because Dimetrodon couldn't keep its body temperature steady on its own.

The sail might also have been used for showing off. Perhaps it was brightly colored to attract mates. Or it could have been used to scare away rivals. This would be similar to how some modern animals use bright colors or large displays.

What Dimetrodon Ate

Dimetrodon was likely the top predator in its environment. It ate many different animals. These included large sharks, aquatic amphibians, and other land animals. Insects were also around in the Early Permian. They were probably part of the food web, feeding smaller reptiles. Some of the first large plant-eating land animals also lived then. These herbivores did not get their energy from aquatic food.

Scientists think the environment where Dimetrodon lived was like the modern Everglades. Dimetrodon probably lived mostly on land. It would have hunted on the banks of rivers or in very shallow water. There is also evidence that Dimetrodon hunted amphibians that were hiding during droughts. Three young amphibians were found in a burrow with Dimetrodon teeth marks. This suggests Dimetrodon dug them up and ate them.

One species, D. teutonis, was found in Germany. It was much smaller, only about 1.7 meters (5.6 feet) long. It was too small to eat the large plant-eaters found there. It probably ate smaller animals and insects. This German site was an upland environment, unlike the lowland areas in Texas. This might explain why there were no large predators like the bigger Dimetrodon species. Those larger predators might have needed big aquatic amphibians for food.

Images for kids

-

D. grandis skeleton, North American Museum of Ancient Life

-

Possible Dimetrodon footprint, Prehistoric Trackways National Monument

See also

In Spanish: Dimetrodon para niños

In Spanish: Dimetrodon para niños