Synapsid facts for kids

Quick facts for kids SynapsidaTemporal range: non-mammalian synapsids: Upper Carboniferous – Lower Cretaceous

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Dimetrodon grandis skeleton at the National Museum of Natural History, U.S.A. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Superclass: | |

| (unranked) | Amniota |

| Class: |

Synapsida

Osborn, 1903

|

| Orders & Suborders | |

For complete phylogeny, see text. |

|

Synapsids are a group of animals that includes all mammals and many older, extinct groups that are related to mammals. The name "Synapsid" means 'fused arch', which refers to a special hole in their skull.

Synapsids are one of two main groups of amniotes. Amniotes are animals whose embryos develop inside a protective membrane, like in an egg or inside the mother. The other main group, called Sauropsids, includes reptiles and birds. Both synapsids and sauropsids started evolving from early amniotes around 345 million years ago. This was during a time called the Carboniferous period.

The two main types of synapsids are the Pelycosaurs and the Therapsids. Pelycosaurs lived from the Pennsylvanian period to the Permian period. Therapsids lived from the Lower Permian period all the way to today, because mammals are therapsids!

Pelycosaurs were the main land animals during the Permian period. But most of them died out during the Permian–Triassic extinction event, a huge event where many species disappeared. After that, therapsids became the dominant land animals in the early Triassic period. However, by the late Triassic, dinosaurs started to take over.

Contents

Early and Advanced Synapsids

Scientists often divide the early synapsids into two groups: the more basic "pelycosaurs" and the more advanced "therapsids."

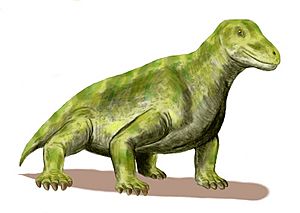

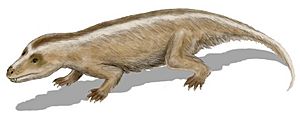

Pelycosaurs were a group of six early synapsid families. They looked a bit like lizards, with legs that sprawled out to the sides. They might have had tough, scaly skin.

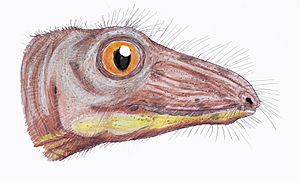

Therapsids were more advanced. They had a more upright way of walking, and some of them might have even had hair. These therapsids are the ancestors of all mammals, including us! So, pelycosaurs led to therapsids, and therapsids led to mammals.

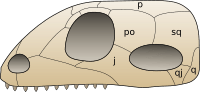

Synapsid Skulls

Skull Openings

One special feature of synapsids is a hole behind each eye on the lower part of their skull. This hole is called a fenestra. It allowed their jaw muscles to attach better, making their bite stronger.

Another group of animals, the diapsids (which include reptiles and birds), also developed holes in their skulls. But they have two holes behind each eye, not just one.

At first, this skull opening only had jaw muscles covering the inside of the head. But in later therapsids and mammals, a bone called the sphenoid grew to close this opening.

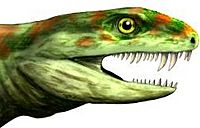

Synapsid Teeth

Synapsids had different kinds of teeth, just like we do! They had canine teeth (pointy teeth), molars (flat teeth for grinding), and incisors (front teeth for biting).

This idea of different tooth types started to appear in some very early reptiles and amphibians. They had larger front teeth on their upper jaw, like early versions of canines. This trait was lost in the reptile group but became very important in synapsids. Early synapsids could even have two or three large 'canines'. But in therapsids, the pattern settled down to one canine in each half of the upper jaw. The lower canines developed later.

How Synapsids Evolved

The oldest known synapsids, Archaeothyris and Clepsydrops, lived about 323 to 299 million years ago during the Pennsylvanian period. They were part of the early group called pelycosaurs.

Pelycosaurs became very successful and spread out, becoming the largest land animals in the late Carboniferous and early Permian periods. Some grew up to 6 meters (about 20 feet) long! They walked with a sprawling gait, were likely cold-blooded, and had small brains. Some, like Dimetrodon, had large sails on their backs that might have helped them warm up their bodies. Most pelycosaurs died out by the middle of the late Permian, or they evolved into the next group: the therapsids.

The therapsids, a more advanced group of synapsids, appeared during the Middle Permian. They included the biggest land animals in the Middle and Late Permian periods. There were plant-eaters and meat-eaters, ranging from tiny animals the size of a rat (like Robertia) to huge plant-eaters weighing a ton or more (like Moschops).

After millions of years of success, most of these animals were wiped out by the Permian–Triassic extinction event about 250 million years ago. This was the biggest extinction event in Earth's history, possibly caused by massive volcanic eruptions.

Only a few therapsids survived and did well in the early Triassic period. These included Lystrosaurus and Cynognathus. But now, they shared the land with early archosaurs, which would soon evolve into dinosaurs. Some archosaurs, like Euparkeria, were small, while others, like Erythrosuchus, were as big as or even bigger than the largest therapsids.

After the Permian extinction, only three main groups of synapsids survived. The first group, called therocephalians, only lasted for about 20 million years into the Triassic. The second group were specialized plant-eaters with beaks, called dicynodonts. Some of these grew very large, weighing a ton or more.

Finally, there were the cynodonts. These became more and more mammal-like as the Triassic went on. They included meat-eaters, plant-eaters, and insect-eaters. An early example was Cynognathus.

Unlike the large dicynodonts, cynodonts generally became smaller and more mammal-like during the Triassic. However, some, like Trucidocynodon, remained large. The very first mammal-like animals evolved from cynodonts about 225 million years ago, in the late Triassic.

As synapsids evolved from early therapsids to cynodonts and then to mammals, their lower jaw changed a lot. The main jaw bone (the dentary) grew larger and replaced other smaller bones. Eventually, the lower jaw became just one big bone. Several of the smaller jaw bones moved into the inner ear, which helped mammals develop excellent hearing.

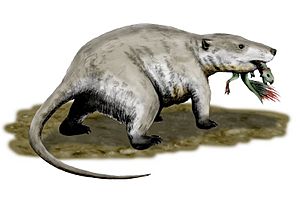

Most of the remaining large cynodonts and dicynodonts disappeared by the end of the Triassic period. This happened even before another extinction event that killed off most large non-dinosaur archosaurs. The synapsids that survived into the Mesozoic Era (the age of dinosaurs) were small. They ranged from the size of a shrew to a badger-like mammal called Repenomamus.

During the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, the remaining non-mammalian cynodonts were small, like Tritylodon. None of them grew larger than a cat. Most of these cynodonts were plant-eaters, though some were meat-eaters. One family, the Tritheledontidae, were meat-eaters and lasted into the Middle Jurassic. Another group, the Tritylodontidae, were plant-eaters and became extinct at the end of the Early Cretaceous. Dicynodonts were thought to have died out by the end of the Triassic, but new fossils found in Cretaceous rocks suggest some might have survived longer.

Today, there are about 5,500 different kinds of living synapsids, and we call them mammals! Mammals include animals that live in water, like whales, and animals that fly, like bats. The largest animal ever known, the blue whale, is a synapsid. Humans are also synapsids. Most mammals give birth to live young, except for monotremes, which lay eggs.

The ancestors of modern mammals, living in the Triassic and Jurassic periods, had very fast metabolisms. This meant they needed to eat a lot of food, usually insects. To help them digest food quickly, these synapsids developed chewing and special teeth for it. Their legs also evolved to move directly under their bodies, instead of out to the side. This allowed them to breathe more easily while moving, which helped support their high energy needs.

Images for kids

-

The sea otter has the densest fur of modern mammals.

See also

In Spanish: Sinápsidos para niños

In Spanish: Sinápsidos para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |