Donald Campbell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Donald Campbell

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Donald Malcolm Campbell

23 March 1921 Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, England

|

| Died | 4 January 1967 (aged 45) Coniston Water, Lancashire, England

|

| Cause of death | High-speed crash during water speed record attempt |

| Body discovered | 28 May 2001 |

| Resting place | Parish Cemetery, Hawkshead Old Road, Coniston |

| Nationality | British |

| Other names | "The Skipper" |

| Occupation | Speed record breaker |

| Known for | Most prolific water speed record breaker of all time |

| Spouse(s) |

Daphne Harvey

(m. 1945–1951)Dorothy McKegg

(m. 1952–1957)Tonia Bern

(m. 1958) |

| Children | 1 |

| Parent(s) | Malcolm Campbell Dorothy Evelyn Whittall |

| Awards | Segrave Trophy (1955) |

Donald Malcolm Campbell (born March 23, 1921 – died January 4, 1967) was a British adventurer who loved speed. He broke eight world speed records on water and land during the 1950s and 1960s. He is the only person ever to set both a world land speed record and a water speed record in the same year (1964). Donald Campbell died in a crash while trying to break the water speed record at Coniston Water in the Lake District, England.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Donald Campbell was born in Kingston upon Thames, England. His father was Malcolm Campbell, who was also a famous speed record holder. Sir Malcolm Campbell set 13 world speed records in the 1920s and 1930s with his special Bluebird cars and boats.

Donald went to St Peter's School, Seaford and Uppingham School. When Second World War started, he wanted to join the Royal Air Force. However, he couldn't because he had rheumatic fever as a child. He then worked as an engineer. After his father passed away in 1948, Donald decided to follow in his footsteps. With help from his father's chief engineer, Leo Villa, Donald started his own journey to break speed records.

Donald Campbell was married three times. He had a daughter named Georgina (Gina) Campbell. He was very superstitious, meaning he believed in certain lucky or unlucky things. For example, he didn't like the color green or the number thirteen. He also thought nothing good ever happened on a Friday.

Chasing Water Speed Records

Donald Campbell began trying to break speed records in 1949. He used his father's old boat, Blue Bird K4, and renamed it Bluebird K4. His first tries were not successful, but he came close to beating his father's record. In 1950, he learned that an American, Stanley Sayres, had set a new record of 160 miles per hour (257 km/h). This was faster than K4 could go without big changes.

Bluebird K4 was changed to make it faster. It was now a "prop-rider" boat, which meant its propeller would skim the water, reducing drag. This made the boat much quicker. In 1951, Bluebird K4 reached 170 mph (274 km/h), but then it broke apart. The next year, Sayres set an even higher record of 178 mph (286 km/h).

Another British speed challenger, John Cobb, was also trying to break the water speed record. He had a jet-powered boat called Crusader. Sadly, Cobb was killed in 1952 when his boat broke up during a record attempt. Donald Campbell was very sad about Cobb's death, but he decided to build a new Bluebird boat to bring the record back to Britain.

Building the Bluebird K7

In 1953, Campbell started working on a new, advanced jet-powered boat called Bluebird K7. It was designed by Ken and Lew Norris. K7 was made of steel and aluminum and had a powerful jet engine. It was designed to go 250 mph (402 km/h). Its unique shape, with two front points and one at the back, made it look like a "pickle-fork."

The name "K7" came from its registration number. It was the seventh boat registered in the "Unlimited" series at Lloyd's, a famous shipping organization.

Setting New Records

Donald Campbell set seven world water speed records with Bluebird K7 between 1955 and 1964. His first record was 202.32 mph (325.60 km/h) on Ullswater in July 1955. He then steadily increased his speed.

- In 1955, he reached 216 mph (348 km/h) on Lake Mead in Nevada, USA.

- On Coniston Water, he set several new records:

* 225 mph (362 km/h) in 1956 * 239 mph (385 km/h) in 1957 * 248 mph (399 km/h) in 1958 * 260 mph (418 km/h) in 1959

To make K7 even faster and more stable, it was updated over the years. It got a new cockpit cover, a small tail fin with a parachute, and other changes to help it handle high speeds better. In 1957, Donald Campbell was given the Order of the British Empire (CBE) award for his achievements.

On November 23, 1964, Campbell set an Australian water speed record of 216 mph (348 km/h) on Lake Bonney Riverland in South Australia.

Land Speed Record Attempt

After his success on water, Donald Campbell wanted to break the land speed record too. In 1956, he started planning to build a car that could beat the existing record of 394 mph (634 km/h). The Norris brothers designed the Bluebird-Proteus CN7, aiming for 500 mph (805 km/h).

Many British companies helped build Bluebird CN7, making it a showcase of British engineering. The car was powered by a special engine that drove all four wheels. It was finished in the spring of 1960.

The 1960 Crash

After some tests, CN7 was taken to the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, USA, where his father had set records years before. The tests went well at first. But on the sixth run, Campbell lost control at over 360 mph (579 km/h) and crashed. The strong design of the car saved his life, but he was injured with a fractured skull and a burst eardrum. CN7 was badly damaged.

Despite the crash, Campbell immediately said he would try again. Sir Alfred Owen, whose company built CN7, offered to rebuild it. This decision greatly affected the rest of Campbell's life.

Trying Again in Australia

Campbell decided not to go back to Utah because he felt the track was too short and in poor condition. A new location was found: Lake Eyre in South Australia. It hadn't rained there for nine years, offering a very long, dry salt lake bed.

By mid-1962, Bluebird CN7 was rebuilt. It was mostly the same car, but with a large tail fin for stability and a stronger cockpit cover. At the end of 1962, CN7 was shipped to Australia. However, just as low-speed runs began, heavy rains came. By May 1963, Lake Eyre was flooded, and the attempt had to be stopped. Campbell faced criticism in the news, even though the bad weather was out of his control.

To make things more difficult, an American named Craig Breedlove set a new land speed record of 407.45 mph (655.74 km/h) in July 1963 with his jet car, "Spirit of America." Even though Breedlove's car didn't follow all the rules for wheel-driven cars, many people saw him as the fastest man on Earth.

Campbell returned to Australia in March 1964. The Lake Eyre track was still not fully dry, and there were more rains. His main sponsor, BP, pulled out, but he found new support from an Australian oil company.

The Record is Set

Finally, in July 1964, Campbell was able to make some fast runs. On July 17, he took advantage of a break in the weather. He made two brave runs on the shortened and still damp track, setting a new official land speed record of 403.10 mph (648.74 km/h).

Campbell was disappointed because the car was designed to go much faster. At one point, CN7 reached 429 mph (690 km/h) on one part of the track. But the official record was lower because of the difficult conditions.

Double Records

After setting the land speed record, Campbell planned to break the water speed record one more time with Bluebird K7. He wanted to achieve his goal of breaking both records in the same year.

After more delays, he finally achieved his seventh water speed record on Lake Dumbleyung near Perth, Western Australia, on December 31, 1964. He reached a speed of 276.33 mph (444.71 km/h).

With this, Donald Campbell became the first, and so far only, person to set both land and water speed records in the same year!

Campbell's land speed record didn't last long as the rules changed, allowing pure jet cars to set records. However, his 429 mph (690 km/h) speed on his final Lake Eyre run remained the highest speed achieved by a wheel-driven car until 2001. Bluebird CN7 is now on display at the National Motor Museum in England.

Final Water Speed Record Attempt

Bluebird K7 Upgraded

To get more attention for his future plans, Campbell decided to try for a water speed record of 300 mph (483 km/h) in 1966. Bluebird K7 was fitted with a new, more powerful Bristol Orpheus engine, taken from a jet aircraft. This engine produced 4,500 pounds of thrust.

The updated boat was brought back to Coniston in November 1966. The trials were difficult due to bad weather and engine problems. By late December, the engine issues were fixed, and Campbell waited for better weather.

The Final Run

On January 4, 1967, the weather was finally good enough. Campbell started his first run just after 8:45 AM. Bluebird sped across the lake, leaving a comet-like spray behind it. It entered the measured kilometer at 8:46 AM, going about 285 mph (459 km/h) and still speeding up. It left the measured kilometer at over 310 mph (499 km/h). The average speed for this first run was 297.6 mph (478.9 km/h).

Instead of stopping to refuel and wait for the water to settle, Campbell decided to make the return run immediately. This was a strategy he had used before. The second run was even faster. Bluebird reached a top speed of 328 mph (528 km/h).

However, the boat started bouncing violently. At its fastest speed, a big bounce caused K7 to drop back onto the water, losing engine power. The boat then lifted out of the water, flipped over, and crashed into the lake. The impact broke the front part of K7, where Campbell was sitting, and the main part of the boat sank quickly.

Donald Campbell's teddy bear mascot, Mr. Whoppit, and his helmet were found in the water. Divers searched for his body but couldn't find it for many years.

What Caused the Crash?

Experts have looked at several reasons for the crash:

- Campbell made the return run immediately, which meant the boat was lighter and might have gone through the waves from his first run. However, later analysis showed this was likely not a major factor.

- Bluebird might have become unstable in the air at such high speeds, especially after losing engine power.

- Some film analysis suggests Bluebird might have hit a bird during earlier test runs, which could have affected its shape and made it harder to control.

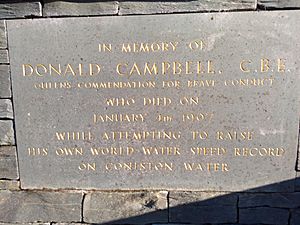

On January 28, 1967, Donald Campbell was honored with the Queen's Commendation for Brave Conduct for his bravery and determination.

Recovery of Bluebird K7 and Campbell's Body

The wreckage of Bluebird K7 was found and recovered by the Bluebird Project between October 2000 and May 2001. Donald Campbell's body was also found in May 2001.

Donald Campbell was buried in Coniston Cemetery on September 12, 2001. His coffin was carried across the lake on a boat, passing over the same measured kilometer where he made his final run. A funeral service was held at St Andrew's Church in Coniston. His widow, Tonia, his daughter Gina, and other family members and fans attended.

Legacy

Together, Donald Campbell and his father set 11 speed records on water and 10 on land.

Donald Campbell's story was told in the 1988 BBC television film Across the Lake, with Anthony Hopkins playing Campbell. In 2003, the BBC showed a documentary about his final record attempt called Days That Shook the World.

An English Heritage blue plaque honors Campbell and his father at Canbury School in Kingston upon Thames, where they lived.

In the village of Coniston, the Ruskin Museum has a display of Campbell's items, including the engine from Bluebird K7 that was recovered in 2001. Campbell's helmet from his last run is also on display.

On March 23, 2021, to mark 100 years since Campbell's birth, two Royal Air Force Hawk jets flew over the Lake District. As they passed over Coniston Water, they dipped their wings in salute, just like an Avro Vulcan jet did the day after his death. Donald's daughter, Gina, placed flowers on the lake.

Restoration of Bluebird K7

On December 7, 2006, Donald Campbell's daughter, Gina Campbell, officially gave the recovered wreckage of Bluebird K7 to the Ruskin Museum in Coniston. The plan is to restore the boat back to how it was on January 4, 1967.

The Bluebird Project is carefully restoring K7 in North Shields, England. They are using many of its original parts, but with a replacement engine of the same type.

In May 2009, permission was given for Bluebird to have a one-time set of test runs on Coniston Water once it's restored. These would be for demonstration only, not to break records.

On March 20, 2018, the restoration was shown on the BBC's The One Show. It was announced that Bluebird K7 would return to the water on Loch Fad in Scotland in August 2018 for handling trials.

First Trials After Restoration

In August 2018, the first part of the restoration was finished. Bluebird was taken to Loch Fad and floated on August 4, 2018. After engine tests, Bluebird completed several test runs on the loch, reaching speeds of about 150 mph (241 km/h). For safety reasons, there are no plans to try for higher speeds.

World Speed Records by Donald Campbell

| Speed | Record Type | Vehicle | Location | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 202.32 mph (325.60 km/h) | Water | Bluebird K7 | Ullswater | July 23, 1955 |

| 216.20 mph (347.94 km/h) | Water | Bluebird K7 | Lake Mead | November 16, 1955 |

| 225.63 mph (363.11 km/h) | Water | Bluebird K7 | Coniston Water | September 19, 1956 |

| 239.07 mph (384.75 km/h) | Water | Bluebird K7 | Coniston Water | November 7, 1957 |

| 248.62 mph (400.12 km/h) | Water | Bluebird K7 | Coniston Water | November 10, 1958 |

| 260.35 mph (418.99 km/h) | Water | Bluebird K7 | Coniston Water | May 14, 1959 |

| 276.33 mph (444.71 km/h) | Water | Bluebird K7 | Lake Dumbleyung | December 31, 1964 |

| 403.10 mph (648.74 km/h) | Land | Bluebird CN7 | Lake Eyre | July 17, 1964 |

See also

In Spanish: Donald Campbell (piloto) para niños

In Spanish: Donald Campbell (piloto) para niños