Elasmotherium facts for kids

Quick facts for kids ElasmotheriumTemporal range: late Pliocene to late Pleistocene, 2.6 mya – ~50 kya

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

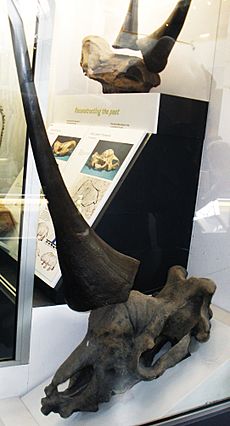

| Elasmotherium skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: |

Elasmotherium

J. Fischer, 1808

|

Elasmotherium was a huge, extinct rhinoceros. It lived from about 2.6 million years ago to around 50,000 years ago. Scientists have found its fossils in Europe and Asia. This giant rhino roamed and ate grass on the Eurasian steppes, which are like big grasslands.

Contents

About the Elasmotherium

Scientists have had many ideas about what Elasmotherium looked like and how it lived. Some thought it trotted like a horse with a horn. Others imagined it hunched over, eating grass like a bison. Some even thought it lived in swamps like a hippo. Today, new science helps us understand it better.

How Big Was It?

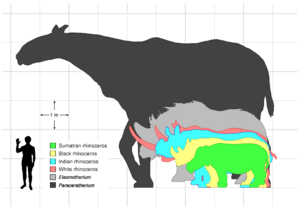

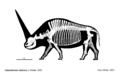

Elasmotherium was one of the biggest rhinos ever! The E. sibiricum species could be up to 4.5 meters (about 15 feet) long. It stood over 2 meters (about 6.5 feet) tall at the shoulder. Another species, E. caucasicum, was even bigger. It could reach at least 5 meters (about 16 feet) long. It weighed about 3.6 to 4.5 tons. That's as heavy as a woolly mammoth! Its front feet had four toes, and its back feet had three.

What Did It Eat?

Elasmotherium was a herbivore, meaning it ate plants. It was a "grazer," which means it mostly ate grass. Like elephants, it probably traveled long distances. This helped it find fresh grass to eat in different areas.

Scientists can tell what an animal ate by looking at its skull. Elasmotherium's head was shaped to reach low to the ground. This shows it was a grazer. Its teeth also give us clues.

Its Amazing Teeth

Elasmotherium had special teeth for eating tough grass. Its cheek teeth were very tall, a feature called hypsodonty. This is like how our teeth wear down, but theirs kept growing! This helped them grind down the tough, gritty grass.

Unlike some other rhinos, Elasmotherium didn't have incisors (front teeth) or canine teeth. Instead, it had a spoon-shaped lower jaw. This helped it grab and tear grass.

Where Did It Live?

Scientists studied the teeth and skulls of many animals. They found that animals with tall teeth and wide muzzles usually live in open areas. These areas include savannas or deserts. Elasmotherium had both these features. This means it likely lived in open grasslands.

Its Horn

Rhinos are known for their horns. These horns are made of keratin, the same stuff as your hair and fingernails! Elasmotherium had a large bump on its forehead. Scientists believe this bump was the base for a huge horn.

Early scientists described this bump as being about 5 inches deep and 3 feet around. They saw grooves on it, which they thought were for blood vessels. These vessels would have fed the tissues that grew the horn. This suggests the horn was very large. Some fossils even show a healed wound on the horn base. This might mean Elasmotherium used its horn to fight other males.

Unlike most horns, rhino horns are unique. They are made entirely of keratin and grow from the skin, not directly from the bone. This means the horn was not attached to the skull bone. It grew from a thick skin layer on the bump. Scientists think this strong connection to the skull means the horn was very heavy.

Elasmotherium Family Tree

Scientists have found hundreds of Elasmotherium fossils. These include skull pieces, teeth, and even almost complete skeletons. They are found across Europe and Asia, from Eastern Europe to China. For example, Kazakhstan alone has 30 sites with E. sibiricum fossils.

How It Fits in the Rhino Family

The rhino family tree is always changing as new fossils are found. Generally, there are two main branches. One leads to smaller rhinos. The other leads to the larger Elasmotherium group. Both started from small rhinos in Asia.

Scientists agree that Elasmotherium and its close relatives form a single group. Over time, these animals became very large. They developed a horn on their forehead, lost their front teeth, and grew very tall cheek teeth for eating grass.

Different Species

Scientists believe Elasmotherium came from an older rhino called Sinotherium. E. caucasicum is thought to be an older species, while E. sibiricum came later.

- E. caucasicum lived in the Black Sea region. Fossils show it lived about 1.1 to 0.8 million years ago. An even older species, E. chaprovicum, lived about 2.6 to 2.2 million years ago.

- E. sibiricum lived from southwestern Russia to western Siberia. It also lived in Ukraine and Moldova. This species is the most recent. Some of the latest fossils found are from Siberia. They are about 50,000 years old.

How Rhinos Evolved

The evolution of rhinos is similar to how horses evolved. Both changed as grasslands and different types of grass spread across the Earth.

Rhino Evolution

The earliest rhinos, from about 42 to 32 million years ago, didn't have horns. Some had tusks, which were modified teeth. Later, some rhinos started to show signs of thick skin or armor on their heads. This might have helped protect them from the tusks of other rhinos.

Rhinos first appeared in North America. Then, they spread to Eurasia when a land bridge appeared. They became very diverse in Eurasia. They also entered Africa, but never had as many different species there. By the Pliocene epoch, they disappeared from North America. In the Pleistocene epoch, they died out in Eurasia. Only African and Southeast Asian species survived.

Elasmotherium appeared in the late Pliocene. It is thought to have come from Sinotherium.

Grassland Evolution

Grasslands changed a lot over millions of years. Early grasslands had C3 plants, which needed a lot of water. Later, C4 plants evolved. These plants needed less water and thrived in warmer, sunnier places. Today, about 46% of grasses are C4.

In the Miocene epoch, small, fast rhinos and horses moved from forests into these new grasslands. They grew larger over time because there was so much food. Some of these animals, like Elasmotherium, became grazers. They developed tall teeth to eat the tough grass.

By the late Miocene, C4 grasslands, like today's savannas, were common. The world became warmer and drier. Smaller rhinos and horses struggled. But huge grazers like Elasmotherium thrived. They could eat large amounts of C4 grass. Their massive size and strong horns protected them from predators. They were truly the "lords of the savanna."

Old Stories About One-Horned Beasts

Many old stories and legends from Europe and Asia talk about a special kind of unicorn or a mysterious one-horned beast. These are different from the delicate, imaginary unicorns we often think of. These legends might be about Elasmotherium.

Stories from Eastern Asia

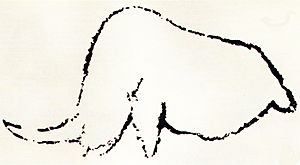

In China, the Qilin (or k'i-lin) is a mythical beast. It was described as having a deer's body, a cow's tail, a sheep's head, a horse's limbs, and a big horn. It was said to be gentle and very tall. Some old Chinese writings mention hunting parties catching a "deer-like" animal with one horn. An old Chinese drawing shows an animal similar to how scientists imagine Elasmotherium: head down for grazing, a horn sticking out from its forehead, and a humped neck and shoulders.

In Siberia, the Yakuts people have a legend about a "huge black bull" with a single horn. They said the horn was so big it needed a sled to move it. Some versions describe it with pale blue or wool-like fur. This "Bull of Winter" is even in their epic poems.

Stories from Western Asia and Europe

In medieval Russia, there are ballads about a beast called the Indrik. It's described as a unicorn that fights a lion. The Indrik lives on a Holy Mountain and digs springs of pure water. At night, it wanders underground, clearing paths with its horn. This story might connect to the Elasmotherium.

The word karkadann was used in Arabic and Persian for a unicorn or rhinoceros. It was said to fight elephants and kill them with its horn. This word comes from the Sanskrit word for rhinoceros.

Some scientists, like Willy Ley, think these legends came from people seeing Elasmotherium long ago. They believe the animals didn't survive into recorded history. However, a medieval traveler named Ibn Fadlan wrote about an animal he saw near the Volga River. He described it as "less than a camel and more like a bull in size." It had a camel's head, a bull's tail, a mule's body, and bull-like hooves. Most importantly, it had a "thick round horn" in the middle of its head, up to five cubits long. He said it ate tree leaves and would attack horsemen. He also mentioned seeing bowls made from the base of its horn. Some people told him it was a rhinoceros. This description sounds very much like Elasmotherium, suggesting it might have lived much later than we thought!

Images for kids