Elias Hill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elias Hill

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1819 |

| Died | March 28, 1872 (aged 52–53) Arthington, Liberia

|

| Occupation | Preacher, civil rights activist |

| Political party | Republican |

Elias Hill (born around 1819 – died March 28, 1872) was an important Baptist minister. He led a group of people from York County, South Carolina who moved to Arthington, Liberia. In May 1871, Elias was attacked by members of the Ku Klux Klan in York County. This attack gained a lot of attention because Elias had a condition from childhood that left his arms and legs weak. He was known for speaking out about rights and equality. He also taught local children how to read and write.

Contents

Elias Hill's Early Life

Elias Hill was born in 1819 in York County, South Carolina. His parents were Dorcas and Elias. When he was seven years old in 1826, he became very ill. This illness left him with weak arms and legs. Some people thought he had polio or muscular dystrophy. His legs stayed very thin, and his arms were weak.

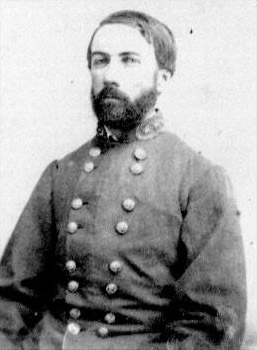

The Hill family was enslaved by a well-known family, which included Daniel Harvey Hill, who later became a general in the Confederate army. When Elias was a boy, white children in York County taught him to read and write. Daniel Harvey Hill was one of those who helped him learn. Elias was very smart and determined. Even though he had a physical condition, he was very intelligent.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, Elias became an ordained Baptist preacher. He traveled to different churches in the South Carolina Piedmont area. He also taught people how to read and write. By 1871, when he was about 50, he became the president of the local Union League. This group worked for the rights of Black people. Elias often held political meetings at his home. He was a popular and powerful preacher, serving a church near Rock Hill, South Carolina.

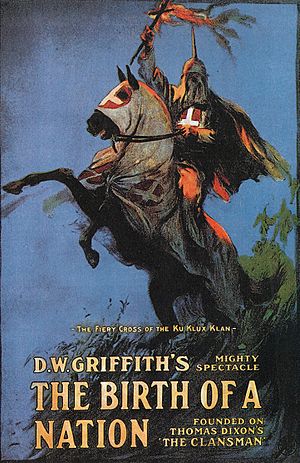

Attacks on Black Leaders

In February 1871, Elias Hill tried to talk with local Ku Klux Klan leaders to keep Black people in the community safe. These talks did not work. Around February 12, many Black men were attacked by large groups of white men wearing masks. These attacks continued for months.

After the Civil War, Jim Williams, a former enslaved person and Union soldier, returned to York County. He worked with Elias Hill to fight for the civil rights of Black people. Jim Williams led a group of Black militia members, part of the Union Leagues. Some white people claimed Williams had threatened them. On March 6, 1871, about forty men took Williams from his home. They attacked him. J. Rufus Bratton, a local Ku Klux Klan leader, was said to be involved.

The attackers also visited the homes of other men in the Union League militia. They took guns but did not find other members. The military, including parts of George Armstrong Custer's Seventh U.S. Cavalry, arrived to try and stop the violence. Elias Hill then stepped in to lead the Union League. In another attack, Elias Hill's nephews, Solomon Hill and June Moore, were forced to say they no longer supported the Republican Party in the local newspaper.

Elias Hill is Attacked

On May 5, 1871, a masked neighbor came to Elias Hill's brother's home, which was next door to Elias's. The neighbor hit Elias's sister-in-law, asking where Elias lived. Then, Elias was pulled by his weak arms and legs into the yard. He was beaten with a horsewhip. The attackers accused him of speaking against the KKK, causing trouble, and other false claims. They threatened to throw him in the river. They told him to stop preaching against the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan also demanded that Elias stop supporting the Republican Party and cancel his newspaper subscription.

This was one of the first violent acts by the Ku Klux Klan that Major Lewis Merrill, a military officer, saw in York County. He could not protect the Black citizens right away. Eight days after the attack, Merrill met with community leaders, asking for change. Even though violence continued that summer, Merrill's efforts eventually helped to break up much of the Klan in the county.

Moving to Liberia

Elias Hill was afraid for his life. He contacted Congressman Alexander S. Wallace and the American Colonization Society to find a way to leave the country. In October 1871, he moved to Liberia with 135 other Black people. Before leaving, he spoke to a government committee. He said that moving away was the best choice. He believed that Black people could not live peacefully in the United States and raise their children as they wished. At least 21 of the 31 families from his church group had been attacked by the Klan or had relatives who were. "That is the reason we have arranged to go away," Hill said.

The group traveled by train to Charlotte, North Carolina, and then to Portsmouth, Virginia. They sailed to Liberia on a ship called the Edith Rose. The trip included 243 passengers and two people who hid on the ship. Most of them, like Hill, were formerly enslaved people. The group settled in Arthington, Liberia.

Life and Death in Liberia

Arthington was a settlement founded in 1869 by Alonzo Hoggard and his church group. Other groups arrived in the following years.

Life in Liberia was harder than the colonists had been told. They believed that few people got sick or died there. However, as many as 20% of new immigrants died from diseases like malaria. When Elias Hill arrived, he found that the government was in "great disorder." Liberia's president, Edward James Roye, was removed from power in late 1871 and was killed in early 1872. Elias Hill died of malaria on March 28, 1872, only six months after arriving in Liberia.

Legacy

The church group from Clay Hill stayed in Arthington. Hill and Moore, a company run by Elias Hill's nephews, became a major business in Liberia. They used their success to support a Baptist school nearby.

Elias Hill's story also inspired characters in books. The character Eliab Hill in Albion W. Tourgée's book, Bricks Without Straw, was partly based on Elias Hill.

The story of Elias Hill also inspired Katharine DuPre Lumpkin's novel Eli Hill. This book was written in the 1950s and published in 2020.

|