Eurasiatic languages facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Eurasiatic |

|

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: |

Before the 16th century, most of Siberia and Western Eurasia; today worldwide |

| Linguistic classification: | Nostratic?

|

| Proto-language: | Proto-Eurasiatic |

| Subdivisions: |

Uralic–Yukaghir

Chukotko-Kamchatkan

Korean–Japanese–Ainu (sometimes included)

Nivkh (sometimes included)

Tyrsenian (sometimes included)

|

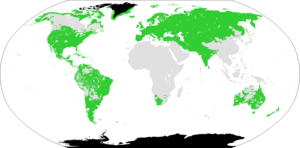

The worldwide distribution of the Eurasiatic macrofamily of languages according to Pagel et al.

|

|

Eurasiatic is a big idea in linguistics, which is the study of language. It suggests that many language families from northern, western, and southern Eurasia might be related. Think of it like a giant family tree for languages!

This idea has been around for over 100 years. A famous linguist named Joseph Greenberg made a popular proposal in the 1990s. More recently, in 2013, Mark Pagel and his team published what they believed was proof for this Eurasiatic language family using statistics.

The exact groups of languages included in Eurasiatic can change depending on who is proposing the idea. But usually, it includes language families like Altaic (which has Mongolic, Tungusic, and Turkic), Chukchi-Kamchatkan, Eskimo–Aleut, Indo-European, and Uralic. Some proposals also add Kartvelian and Dravidian languages, plus language isolates like Nivkh and Etruscan.

It's important to know that most linguists today don't accept the Eurasiatic idea. They also don't accept many other similar "macrofamily" ideas, except for the Dené–Yeniseian languages connection, which has gained some support.

Contents

Exploring the Eurasiatic Idea

The concept of Eurasiatic has a long history, with different scholars adding their own ideas and research over time.

Early Clues and Patterns

In 1994, a linguist named Merritt Ruhlen pointed out an interesting pattern. He said that in some language groups, plural nouns (more than one) often end with "-t", while dual nouns (exactly two) often end with "-k".

This pattern was first noticed in 1818 by Rasmus Rask in languages now called Uralic and Eskimo–Aleut. But it also shows up in Tungusic, Nivkh, and Chukchi–Kamchatkan languages. All these languages are part of what Greenberg later put into Eurasiatic. Ruhlen believed this pattern was unique to Eurasiatic languages.

Greenberg's Big Idea

Joseph Greenberg was a key figure in the Eurasiatic discussion. In the 1950s, he developed a method called "mass comparison" to group languages. He used this method to study African languages first.

In 1998, he used mass comparison to suggest the Eurasiatic language family. Then, in 2000, he wrote a whole book about it. He presented evidence from both sounds (phonetics) and grammar (morphology) to support his idea. The main part of his argument was 72 grammatical features that he thought were shared across the different language families he studied.

Why Some Experts Disagree

Many linguists have not accepted Greenberg's Eurasiatic idea. They often say that his mass comparison method isn't reliable. A big criticism is that his method assumes words with similar sounds and meanings come from the same origin.

However, language changes a lot over thousands of years. Experts believe that after 5,000 to 9,000 years, it's very hard to find traces of original sounds and meanings. So, applying these methods to very old "superfamilies" is seen as questionable. Also, similar-sounding words can appear by chance or be loan words (words borrowed from another language).

Stefan Georg and Alexander Vovin, two linguists, looked closely at Greenberg's claims. They agreed that looking at grammatical features is the right way to find language families. But they doubted Greenberg's conclusions. They found "too many misinterpretations, errors and wrong analyses" in his work. They concluded that his attempt to prove Eurasiatic had failed.

The Boreal Hypothesis

In the 1980s, a Russian linguist named Nikolai Dmitrievich Andreev had a similar idea called the Boreal hypothesis. He linked the Indo-European, Uralic, and Altaic language families. He even suggested 203 shared word roots for his Boreal macrofamily. After he passed away in 1997, Sorin Paliga continued to develop this hypothesis.

Pagel's Statistical Evidence

In 2013, Mark Pagel and his colleagues published new statistical evidence for Eurasiatic. They wanted to address the criticisms about language changing too much over time.

How Words Change Over Time

Their earlier work showed that most words change or are replaced every 2,000 to 4,000 years. But they found some words, like numbers, pronouns (words like "I," "you"), and certain adverbs (words that describe verbs), change much slower. These "ultraconserved words" can last 10,000 to 20,000 years or even longer! They found this was true across many modern languages.

Their Research Method

Pagel's team used reconstructed "proto-words" (very old, imagined words) from seven language families. They focused on the 200 most common words from the Swadesh list, which is a list of basic vocabulary.

Instead of trying to "prove" that specific word pairs were related, they looked at patterns across many possible word pairings. They treated each pairing as a chance event that could have errors.

What They Found

They found that words used more often were more likely to have "cognates" (related words) across many language families. For example, words used more than once per 1,000 spoken words were 7.5 times more likely to be judged as related. Pronouns and adverbs also showed this pattern. This matched their prediction that frequently used words would be more stable over time.

The researchers argued that their ability to predict these words, even without knowing their exact sound similarities, helped counter the usual criticisms. They said that if their results were just due to chance, then all words, no matter how often they were used, should show similar resemblances. But their data showed a clear difference.

Dating the Language Family

The team used a computer simulation to estimate the age of the language families. They estimated that the Eurasiatic family originated about 14,450 to 15,610 years ago. This timing fits with ideas that these languages spread as glaciers retreated in Eurasia at the end of the last ice age, around 15,000 years ago.

Criticisms of Pagel's Work

Many experts in historical linguistics are still doubtful about these conclusions. Sarah Thomason, a linguist, questioned the accuracy of the data used by Pagel's team. She noted that the database they used often listed many possible reconstructed words for a single meaning, which could increase the chance of accidental matches.

Pagel's team thought about this criticism. They argued that if errors were the cause, then less common words (which have more possible reconstructions) should show more connections, but their data showed the opposite.

Thomason also pointed out that the database was mainly built by people who already believed in a larger "Nostratic" superfamily (which includes Eurasiatic). This could mean the data was biased towards finding connections. Pagel's team admitted this bias might exist but thought it was unlikely to have affected their results much. They noted that some words usually thought to be very old (like numbers) didn't appear on their list of strong connections, while other less important words (like bark and ashes) did.

Another linguist, Asya Pereltsvaig, argued that words change too much over time to keep their sound and meaning for 15,000 years. She showed how much English words have changed in just 1,500 years. She also suggested that grammatical features are more reliable than words for finding language relationships.

Pagel's team also considered if language borrowing (words moving between languages) could explain their results. They thought this was unlikely because the language groups cover a huge area, and frequently used words are usually not borrowed in modern times.

How Eurasiatic Fits In

The Eurasiatic idea is often seen as part of even bigger language family proposals.

Connections to Other Proposed Families

According to Greenberg, Eurasiatic is most closely related to Amerind, a proposed language family in the Americas. He suggested that both Eurasiatic and Amerind spread about 15,000 years ago into areas that became open after the Arctic ice cap melted. He believed these two families are quite different from other Old World language families, which represent much older groupings. However, like Eurasiatic, the Amerind proposal is not widely accepted.

Eurasiatic also shares many language families with another proposed macrofamily called Nostratic. Many Nostratic theorists see Eurasiatic as a subgroup within Nostratic, alongside families like Afroasiatic, Kartvelian, and Dravidian. The database used by Pagel's team also views Eurasiatic as a part of Nostratic. But again, the Nostratic family is not accepted by most mainstream linguists.

Harold C. Fleming even includes Eurasiatic as a subgroup of an even larger hypothetical family called Borean.

Subdivisions of Eurasiatic

The exact way Eurasiatic is divided into smaller groups can vary. But it usually includes Turkic, Tungusic, Mongolic, Chukchi-Kamchatkan, Eskimo–Aleut, Indo-European, and Uralic.

Greenberg listed eight main branches for Eurasiatic:

- Altaic (Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic)

- Chukchi-Kamchatkan

- Eskimo–Aleut

- Etruscan

- Indo-European

- "Korean-Japanese-Ainu"

- Nivkh

- Uralic–Yukaghir

Pagel's team used a slightly different list of seven language families: Altaic, Chukchi-Kamchatkan, Dravidian, "Inuit-Yupik" (a group of Eskimo languages), Indo-European, Kartvelian, and Uralic.

Here's a simplified way to see the branching of Eurasiatic, following Greenberg's ideas:

- Eurasiatic

- Indo-European (most experts agree this is a real family)

- Uralic–Yukaghir (this grouping is a hypothesis)

- Uralic (most experts agree this is a real family)

- Yukaghir (most experts agree this is a real family)

- Nivkh (most experts agree this is a real family)

- Chukotko-Kamchatkan (most experts agree this is a real family)

- Eskaleut (most experts agree this is a real family)

- Altaic (this grouping is debated)

- Korean–Japanese–Ainu (this grouping is a hypothesis)

- Koreanic (most experts agree this is a real family)

- Japonic (most experts agree this is a real family)

- Ainu (most experts agree this is a real family)

- Tyrsenian † (a group of three extinct languages; their link to Eurasiatic is very uncertain because we don't have much information about them)

Jäger's (2015) Analysis

In 2015, a computational study by Jäger created a family tree for languages in Eurasia. It showed "Eurasiatic" as one large branch, with other families like Yeniseian, Dravidian, and Sino-Tibetan as separate branches.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Where Eurasiatic Languages Might Have Spread

Merritt Ruhlen suggested that the way Eurasiatic languages are spread across the world shows they came from different migrations than the Dené–Caucasian family. He thought Dené–Caucasian was older, and Eurasiatic spread later, taking over many areas.

This left Dené–Caucasian speakers mostly in isolated places like the Basques in the Pyrenees Mountains, Caucasian peoples in the Caucasus Mountains, and the Burushaski in the Hindu Kush Mountains. These areas were hard to reach, which helped the languages survive.

However, most linguists, including Lyle Campbell, Ives Goddard, and Larry Trask, disagree with the idea of a Dené–Caucasian family.

Based on the analysis of those "ultraconserved words," the last common ancestor of the Eurasiatic family is estimated to be about 15,000 years old. This suggests these languages might have spread from a "refuge" area after the last ice age ended.

See also

- Indo-Semitic languages

- Indo-Uralic languages

- Nostratic languages

- Proto-Human language

- Ural–Altaic languages

- Uralo-Siberian languages

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |