FBI Index facts for kids

The FBI Indexes were a system the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) used to keep track of American citizens and other people. This happened before computers were common. The system started with paper cards. J. Edgar Hoover first put these lists together when he worked at the Bureau of Investigations, which later became the FBI.

The FBI used these lists to watch people they thought might be a danger to the country's safety. The lists were split into different groups based on how dangerous someone was believed to be.

Contents

The First FBI Tracking System

In 1919, during a time called the First Red Scare, William J. Flynn put J. Edgar Hoover in charge of the General Intelligence Division (GID). Hoover had worked as a library clerk. He used his skills to create a detailed system with many linked cards.

The GID took files from the Bureau of Investigations and organized them using these index cards. By 1939, Hoover had more than 10 million people listed in the FBI's system.

The GID officially ended in 1924 because some people, like William J. Donovan, thought it might not be allowed by the country's laws. However, Hoover and the FBI kept growing the Index system. They used it for the agency, for Hoover himself, and for his political friends until the 1970s. Today, the FBI can still access these Index files.

There were many different Index lists. Some examples include:

- The Reserve Index: For important people who could be "arrested and held" if there was a national emergency.

- The Custodial Index: This list included 110,000 Japanese Americans who were held in internment camps during World War II.

- The Deviant Index

- The Agitator Index

- The Communist Index

- The Administrative Index: This one combined several older lists.

Even though we don't have a full list of all the Index names, Hoover and the FBI used their system to track Native American and African American civil rights activists in the 1960s and 1970s. They also tracked people protesting the Vietnam War and some college students.

The Custodial Detention Index

The Custodial Detention Index (CDI) was created between 1939 and 1941. It was part of a program called the "Custodial Detention Program" or "Alien Enemy Control."

J. Edgar Hoover said this list came from his General Intelligence Division. He claimed it helped the FBI find people, groups, and organizations involved in "dangerous activities," like spying. Congressman Vito Marcantonio called it "terror by index cards." Senator George W. Norris also complained about it.

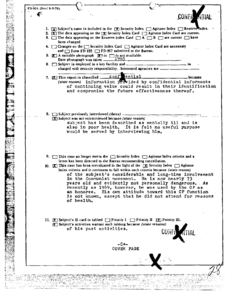

The Custodial Detention Index listed suspects and people thought to be a danger. They were put into "A," "B," or "C" categories. Those in Category A were meant to be arrested and held right away if a war started. Category A included leaders of groups linked to Axis countries (like Germany, Italy, and Japan). Category B was for members thought to be "less dangerous," and Category C was for people who supported these groups.

However, the categories were often based on how much someone seemed to care about their home country, not on how much harm they could actually cause. For example, leaders of cultural groups could be put in Category A.

This program created secret files on individuals. These files often included information that wasn't proven, like rumors or phone tips from unknown people. Information was also gathered without legal permission, using things like mail covers (watching mail), wiretaps, and secret searches. While the program mainly focused on Japanese, Italian, and German "enemy aliens" (people from enemy countries), it also included some American citizens born in the U.S.

The program ran without approval from Congress and without court supervision. It went beyond what the FBI was legally allowed to do. If someone was accused, they were investigated and put on the index. They stayed on the list until they died.

The Custodial Detention Index was later used for the Japanese American internment. This happened after President Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066. Even though some say Hoover didn't agree with these actions, he and the FBI created the list. From this list, 110,000 people were held, and 70,000 of them were born in America.

When Attorney General Francis Biddle found out about the Index, he called it "dangerous, illegal" and ordered it to stop. But J. Edgar Hoover simply renamed it the Security Index and told his staff not to talk about it.

The Rabble Rouser Index

Records from the Rabble Rouser Index are available online. You can find them through The Vault, which is the FBI's FOIA Library. The Internet Archive also has a copy with more details. Plus, a collection of FBI files, including the Rabble Rouser Index, is kept at the National Archives.

People on the Rabble Rouser Index

Some well-known people on this list included:

- Saul Alinsky — a political thinker

- James H. Madole — from the National Renaissance Party

- Floyd B. McKissick — from SNCC

- Jerry Rubin — an anti-war activist

- Adam Clayton Powell Jr. — a Congressman from New York

- John A. Wilson — a council member in Washington D.C.

- Howard Zinn — a historian and philosopher

Groups on the Rabble Rouser Index

Important groups listed on FBI form FD-307 included:

- American Nazi Party

- Anti-Vietnam War groups

- Black Nationalist groups

- Black Panther Party

- Communist groups

- Congress of Racial Equality

- Ku Klux Klan groups

- Latin American groups

- Minutemen

- Nation of Islam

- National States Rights Party

- Progressive Labor Party

- Puerto Rican Independence groups

- Revolutionary Action Movement

- Southern Christian Leadership Conference

- Students for a Democratic Society

- Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee

- Socialist Workers Party

- Workers World Party

The Reserve and Security Indexes

The Security Index was an FBI list of people who might do things that could harm the country's safety during an emergency. This list also included people who could be arrested if a U.S. President started an Emergency Detention Program.

The Reserve Index, on the other hand, listed people who were considered "left-wing" or suspected of being a Communist. For example, by the 1950s, the Chicago FBI office had 5,000 names on the Security Index and 50,000 on the Reserve Index. Someone on the Reserve Index could be moved to the Security Index if they seemed to be a threat during a national emergency.

These two indexes had different color codes for their files. The Security Index files were all white. The Reserve Index files had different colors depending on what job the person had.

A famous person on the Reserve Index was Martin Luther King. The FBI had been watching his work with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference since 1957. By 1962, he was added to the FBI index. This was because two of his advisors were linked to the U.S. Communist Party, even though he didn't meet the rules for being on the Security Index.

The Security Index later joined with the Agitator Index and the Communist Index. In 1960, it was renamed the Reserve Index. This new Reserve Index had a Section A for teachers, doctors, lawyers, entertainers, and other influential people who were not politically conservative. Hoover had Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. added to the Reserve Index, Section A. This was done because of King's civil rights work and his popularity around the world.

This index was renamed again in 1971 to the Administrative Index (ADEX). It was supposedly stopped in 1978. However, the records are still kept as "inactive" at FBI headquarters and its 29 offices.

The Administrative Index (ADEX)

ADEX, or Administrative Index, was used from 1971 to January 1978. It combined the Security Index, the Agitator Index, and the Reserve Index. It was used to track people "thought to be a threat to the country's safety." ADEX had four different categories.

A good example of these files and why people were put into categories is the case of historian Howard Zinn. He was known for criticizing the government. In his FBI files, two pages show an agent saying he should be in Category III:

He was a member of the Communist Party from 1949 to 1953. He was a main critic of the United States Government's policies. He was often seen at anti-war protests until 1972. He organized a protest rally in the summer of 1971 to speak out against serious charges against Father Berrigan and others.

It is suggested that this person be included in ADEX, Category III. This is because he has taken part in activities of revolutionary groups in the last five years. This is shown by his actions and statements, confirmed by reliable sources.

Singer Paul Robeson was also on ADEX as Category III. This was "because of his long-time close contact with leaders of the Communist Party USA. The Communist Party honored him as recently as 1969."

See also

In Spanish: Índice del FBI para niños

In Spanish: Índice del FBI para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |