William J. Donovan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bill Donovan

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| United States Ambassador to Thailand | |

| In office September 4, 1953 – August 21, 1954 |

|

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Edwin F. Stanton |

| Succeeded by | John Peurifoy |

| Director of the Office of Strategic Services | |

| In office June 13, 1942 – October 1, 1945 |

|

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt Harry S. Truman |

| Deputy | John Magruder |

| Preceded by | Himself (as Coordinator of Information) |

| Succeeded by | John Magruder (as Director of the Strategic Services Unit) |

| Coordinator of Information | |

| In office July 11, 1941 – June 13, 1942 |

|

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as Director of the Office of Strategic Services) |

| Assistant Attorney General for the Antitrust Division | |

| In office 1926–1927 |

|

| President | Calvin Coolidge |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | John Lord O'Brian |

| Assistant Attorney General for the Criminal Division | |

| In office 1924–1925 |

|

| President | Calvin Coolidge |

| Preceded by | Earl J. Davis |

| Succeeded by | Oscar Luhring |

| United States Attorney for the Western District of New York | |

| In office 1922–1924 |

|

| President | Warren G. Harding |

| Preceded by | Stephen T. Lockwood |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Penney Jr. |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

William Joseph Donovan

January 1, 1883 Buffalo, New York, U.S. |

| Died | February 8, 1959 (aged 76) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Education | Niagara University Columbia University (BA, LLB) |

| Civilian awards |

|

| Nickname | "Wild Bill" |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Major General |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | Pancho Villa Expedition World War I

Russian Civil War

|

| Military awards |

|

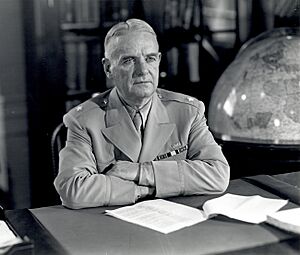

William Joseph "Wild Bill" Donovan (January 1, 1883 – February 8, 1959) was an American soldier, lawyer, spy, and diplomat. He is most famous for leading the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during World War II. The OSS was a very important group that later helped create the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Many people call him the "founding father" of the CIA. There's even a statue of him at the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

Donovan was a brave soldier in World War I. He is thought to be the only person to have received four very special awards: the Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, the Distinguished Service Medal, and the National Security Medal. He also earned the Silver Star and Purple Heart. He received awards from other countries too, for his service in both World Wars.

Contents

Early Life and Education

William Joseph Donovan was born on January 1, 1883, in Buffalo, New York. His family was of Irish background. He was the oldest of several children. His family taught him about being tough and honoring his country.

Donovan went to St. Joseph's Collegiate Institute, a Catholic school. He played football and won awards for speaking. He then attended Niagara University, where he studied to become a lawyer. He thought about becoming a priest but decided against it.

Later, he transferred to Columbia University. There, he explored different religions and joined a fraternity. He was also a football star and won more speaking awards. He was even voted "most modest" and "one of the handsomest" in his class of 1905.

Becoming a Lawyer and Soldier

After college, Donovan studied at Columbia Law School. He was classmates with Franklin D. Roosevelt, who would later become president. In 1909, he started working at a law firm in Buffalo. A few years later, he opened his own firm.

In 1912, Donovan helped create a cavalry troop for the New York National Guard. This unit was called to serve in 1916. They went to the U.S.–Mexico border to help in the fight against Pancho Villa. During this time, Donovan learned a lot about military strategy. In 1914, he married Ruth Rumsey.

In 1916, Donovan traveled to Berlin to help get food and clothing to people in Belgium, Serbia, and Poland during the war. When he returned, he joined the famous "Fighting Irish Regiment," the 69th New York Infantry. This regiment became part of the 42nd Division, also known as the "Rainbow Division." Douglas MacArthur was a leader in this division.

World War I Heroics

During World War I, Major Donovan led a battalion of the 165th Infantry in France. He was injured by shrapnel in his leg and almost blinded by gas. He was offered a French award, the Croix de Guerre, but he turned it down. He did this because a Jewish soldier who helped him wasn't also honored. Once the other soldier received the award, Donovan accepted his.

He earned the Distinguished Service Cross for leading a brave attack during the Aisne-Marne campaign. Many soldiers in his regiment died in this battle. The 1940 movie The Fighting 69th showed these events.

Donovan's amazing strength and endurance earned him the nickname "Wild Bill" from his soldiers. This name stayed with him for the rest of his life. Even though he said he didn't like it, his wife knew he secretly loved it.

He later became the commander of the 165th Regiment. In another battle in October 1918, he bravely led his men. He was shot in the knee but kept directing his soldiers. For his courage, he received a second Distinguished Service Cross. After the war ended in November 1918, Donovan stayed in Europe for a while. When he returned to New York in 1919, he was a colonel. People thought he might run for governor, but he chose to go back to his law practice.

Between the World Wars

After World War I, Donovan traveled a lot for both business and to gather information. He visited Japan, China, Korea, and even Siberia during the Russian Civil War. He also traveled in Europe, doing business for J. P. Morgan and learning about international politics.

From 1922 to 1924, he worked as a U.S. Attorney in New York while also running his private law firm. In 1923, he finally received the Medal of Honor for his bravery in the battle at Landres-et-Saint-Georges. He said the medal belonged to all the soldiers, especially those who didn't come home.

Donovan became known as a strong crime-fighter. In 1924, President Calvin Coolidge appointed him as an Assistant Attorney General. Donovan was in charge of the criminal division. He was known for hiring women and for being very effective in court. He and his wife were popular in Washington, D.C.

He later became head of the antitrust division. He was often the acting Attorney General. People admired his strong arguments in court. He was even considered for governor of New York or Vice President. In 1929, he left the Justice Department and started a new law firm in New York City. He handled many business cases and had famous clients like Mae West.

In 1932, Donovan ran for Governor of New York as a Republican. He lost to the Democratic candidate, Herbert Lehman.

World War II and the OSS

Before World War II, Donovan traveled a lot in Europe and Asia. He met with leaders like Benito Mussolini and even people in Nazi Germany. He believed a second major war in Europe was coming. He was not a friend of dictators and worked to protect his Jewish clients from the Nazis.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt valued Donovan's insights, even though they were from different political parties. Roosevelt saw Donovan as an important advisor. As World War II began in Europe in 1939, Roosevelt started preparing the U.S. for war. Donovan wanted to help.

In 1940 and 1941, Donovan traveled to Britain as an unofficial messenger for Roosevelt. He wanted to see if Britain could stand up to Germany. He met with important British leaders, including Winston Churchill and British spy chiefs. Donovan and Churchill became good friends. Churchill was so impressed that he gave Donovan access to secret information. Donovan returned to the U.S. believing Britain could win and wanted to create an American spy agency like Britain's. He urged Roosevelt to help Churchill.

Donovan also met with William Stephenson, a British spy known as "Intrepid." Stephenson and his deputy, Dick Ellis, helped Donovan plan the new American intelligence agency. Donovan wanted his own operations, not just to be an assistant to the British.

Creating the OSS

On July 11, 1941, President Roosevelt created the position of Coordinator of Information (COI) and named Donovan its head. Before this, the U.S. government didn't have a formal spy agency. Different parts of the government had their own small intelligence groups, but they didn't work together well. Many of these groups saw Donovan's new agency as a threat.

Donovan started building a central intelligence program. He worked closely with Dick Ellis. The COI's headquarters were set up in Rockefeller Center in New York. Donovan recruited many different kinds of people, from smart thinkers and artists to people with unusual backgrounds. He also hired many women spies, even though some people thought women weren't suited for such work. Famous recruits included film director John Ford, chef Julia Child, and psychologist Carl Jung.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Roosevelt told Donovan that creating the COI was a good idea. Donovan warned against putting Japanese-Americans in internment camps, saying it would harm loyal Americans and help Japanese propaganda.

Donovan set up spy and sabotage schools. He created fake companies and worked secretly with international businesses and even the Vatican. He also oversaw the invention of new spy tools like special guns, cameras, and bombs.

In 1942, the COI became the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and was placed under the military. Donovan was promoted to colonel, then brigadier general, and finally major general. Under his leadership, the OSS carried out successful spy and sabotage missions in Europe and parts of Asia.

The OSS helped prepare for the Allied invasion of North Africa in 1942. Donovan himself took part in Allied landings in Italy in 1943 and 1944. He was very active in almost every part of World War II. He visited the Balkans, China, and Burma. He even met with Vyacheslav Molotov in Moscow to arrange cooperation between the OSS and the Soviet secret police.

By 1943, Donovan's relationship with British officials became difficult. They had different ideas about how to fight the war and what the world should look like after the war. The British accused the OSS of acting like "cowboys and red Indians." Still, by May 1944, Donovan had about 11,000 American officers and foreign agents working in many important cities. He even received information from Catholic priests in Europe who were secretly spying.

On D-Day, Donovan was on one of the ships that landed in Normandy. He went ashore and faced German fire. He reported directly to Roosevelt about what he saw. He said the invasion showed that German forces were no longer "Big League." He also met with Pope Pius XII in Italy.

A big success for the OSS was providing secret information from southern France before the Allied landing on the French Riviera in August 1944. Thanks to Donovan's spies, the invading army knew everything about the beaches and German positions. Donovan was there for that invasion too. In the final days of the war in Europe, Donovan was in London. He received reports from all over Europe and knew German positions better than their own generals.

Postwar Plans and Nuremberg Trials

As World War II ended in 1945, Donovan wanted to keep the OSS going. He proposed creating a permanent intelligence agency. However, President Roosevelt was not fully convinced. After Roosevelt's death, the new president, Harry S. Truman, was against Donovan's plan. Many military leaders praised the OSS, but critics called it "an arm of British intelligence" or even an "American Gestapo."

Donovan strongly pushed for trying war criminals after the war. He started collecting evidence as early as 1943. When Truman appointed Robert H. Jackson to lead the prosecution of Nazi war criminals, Jackson asked Donovan to join his team. Donovan brought 172 OSS officers to help. They interviewed survivors, found Nazi documents, and gathered other evidence. Donovan even suggested holding the trials in Nuremberg. Jackson later called Donovan a "godsend."

Donovan interrogated many prisoners in Nuremberg, including Hermann Göring. However, Donovan and Jackson disagreed on some things. Donovan felt Jackson wanted to indict too many people, which went against American ideas of fairness. Donovan also criticized Jackson's lack of courtroom experience. Because of these disagreements, Jackson removed Donovan from the team. In January 1946, Truman awarded Donovan the Distinguished Service Medal.

Founding the CIA

In 1946, Donovan went back to practicing law. He also became chairman of the American Committee on United Europe (ACUE), which worked to unite Europe against the new threat of Communism.

Meanwhile, President Truman moved forward with plans for a new intelligence agency. In 1946, he approved a weaker "Central Intelligence Group." Donovan warned it would not be effective, calling it a "debating society." He was right. As the Cold War grew, Truman realized he needed a stronger spy service. In 1947, he asked Congress to approve plans for a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), much like what Donovan had suggested. Donovan himself secretly lobbied Congress to pass the law that created the CIA. This was a big win for Donovan's vision. Many former OSS members went on to become important figures in the CIA.

Donovan wanted to lead the CIA, and many people supported him. But Truman chose Admiral Roscoe Hillenkoetter instead. Donovan still worked behind the scenes to help the CIA. He suggested covert operations and shared information from behind the Iron Curtain. Truman, however, was angry, seeing Donovan as interfering.

In the 1952 election, Donovan campaigned for Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had become a good friend. After Eisenhower won, Donovan hoped to lead the CIA, but Eisenhower appointed Allen Dulles. Instead, Eisenhower offered Donovan the job of Ambassador to France, which Donovan turned down. However, in August 1953, he accepted the post of Ambassador to Thailand. He felt he could work independently there, and Thailand was important during the Cold War.

As ambassador, Donovan often traveled to Vietnam. He believed it could become a communist country. He was involved in setting up CIA operations throughout Southeast Asia. He resigned from his ambassador role in August 1954. After returning to the U.S., he resumed his law practice. He also worked with groups like the People to People Foundation and the International Rescue Committee.

Death and Legacy

Donovan began showing signs of memory problems while in Thailand. He was hospitalized in 1957. He died on February 8, 1959, at age 76, from complications of a brain condition. When he died, the CIA sent a message saying, "The man more responsible than any other for the existence of the Central Intelligence Agency has passed away." He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. After his death, he received the Freedom Award.

Donovan is a member of the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame. He is known as the "Father of American Intelligence" and the "Father of Central Intelligence." The CIA headquarters building has a statue of him in the lobby. His life was full of brave and sometimes surprising actions, all well-documented in declassified wartime records.

William J. Donovan Award

The William J. Donovan Award was created by the OSS Society, which Donovan founded in 1947. This award honors people who have shown the same qualities as General Donovan in their public service to the United States. Famous people who have received this award include President Dwight D. Eisenhower and President George H. W. Bush.

Personal Life

Donovan's son, David Rumsey Donovan, was a naval officer who served bravely in World War II. His grandson, William James Donovan, also served in the military and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Awards and Decorations

U.S. Awards

| Medal of Honor | |

| Distinguished Service Cross | |

| Distinguished Service Medal with one oak leaf cluster | |

| Silver Star | |

| Purple Heart with two oak leaf clusters | |

| National Security Medal | |

| Mexican Border Service Medal | |

| World War I Victory Medal with silver campaign star | |

| Army of Occupation of Germany Medal | |

| American Defense Service Medal | |

| American Campaign Medal | |

| European–African–Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with Arrowhead device, two silver and one bronze campaign stars | |

| European–African–Middle Eastern Campaign Medal (second ribbon required for accoutrement spacing) | |

| Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with Arrowhead device and two bronze campaign stars | |

| World War II Victory Medal | |

| Army of Occupation Medal with 'Germany' clasp | |

| Armed Forces Reserve Medal with bronze hourglass device |

Foreign Awards

| Knight, Légion d'honneur (France) (World War I) | |

| Commander, Légion d'honneur (France) (World War II) | |

| Croix de guerre with Palm and Silver Star (France) (World War I) | |

| Honorary Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire | |

| Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Sylvester (Vatican) (Italian: Ordine di San Silvestro Papa) | |

| Order of the Crown (Italy) (Italian: Ordine della Corona d'Italia) | |

| Croce al Merito di Guerra (Italy) | |

| Commander's Cross with Star of the Order of Polonia Restituta (Poland) | |

| Grand Officer of the Order of Léopold of Belgium with Palm | |

| Czechoslovakian War Cross (1939) | |

| Grand Officer of the Order of Orange Nassau (Netherlands) | |

| Grand Cross of the Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav (Norway) | |

| Knight Grand Cross (First Class) of The Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant (Thailand) |

See Also

- Dick Ellis

- List of Medal of Honor recipients for World War I

- List of members of the American Legion

- List of U.S. political appointments that crossed party lines

- Special Activities Division

- Tightrope Walker (1979), sculpture on the Columbia University campus commemorating Donovan