Foreign Cattle Market facts for kids

The Foreign Cattle Market in Deptford was a huge place in London where animals from other countries were brought to be sold and slaughtered. It operated from 1872 to 1913. This market was super important because it supplied about half of London's fresh meat!

It was built on the old Deptford Dockyard right by the River Thames. The City of London owned it. All the animals, like cows, sheep, and pigs, came from overseas by special boats. They had to stay in quarantine (a special isolated area) and be killed within 10 days of arriving. No animal was allowed to leave the market alive. This rule was very strict to stop animal diseases from spreading into Britain.

The market was enormous. It could hold 8,500 cattle and 20,000 sheep at one time. There were also 70 slaughterhouses (places where animals are killed for meat). This market was a big part of what people call the "first globalisation," connecting London to farms and ranches all over the world.

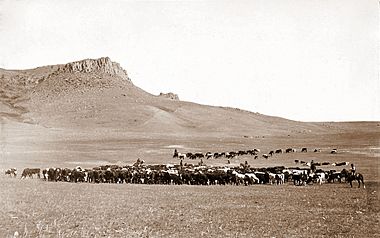

Animals came from far-off places like the Great Plains of America, where cowboys rounded them up. They also came from Argentina, Australia, and New Zealand. Sometimes, the journeys were very tough for the animals.

Contents

Why London Needed New Markets

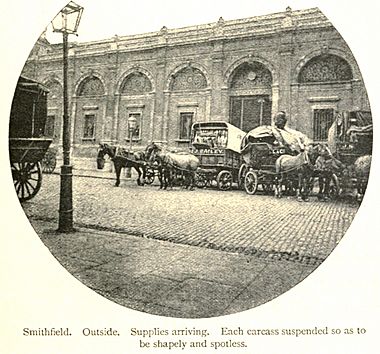

For many years, London's main cattle market was at Smithfield. But by the 1800s, it became too small and crowded. Imagine cows being driven through busy streets like Oxford Street! It caused huge traffic jams and was dangerous.

The End of Smithfield's Livestock Market

Since there was no refrigeration back then, butchers bought live animals. Then they would slaughter them in their own shops. The market at Smithfield was a public health problem because it was so dirty.

So, in 1855, the government decided to move London's livestock market. It went to a new site in Islington. Later, Smithfield was rebuilt into the meat market you can still see today.

The Metropolitan Cattle Market

The new market in Islington was called the Metropolitan Cattle Market. It was built in Copenhagen Fields.

London's population was growing fast, and people had more money. This meant they wanted to eat more meat. British farms couldn't keep up with this demand. So, in the 1840s, the government allowed foreign cattle to be imported without extra taxes. This was the start of "free trade" and the "first globalisation."

Trains brought animals to the Metropolitan Cattle Market from all over Britain and Ireland. More and more animals also came from Europe. A scientist named John Gamgee warned that importing animals freely was risky. He said it could bring in diseases. But businesses wanted the trade to continue, so it did.

As train travel improved in Europe, cattle came from as far away as Hungary and Russia. Russia often had a terrible disease called cattle plague (rinderpest). This disease spread quickly to Britain from the Metropolitan Cattle Market.

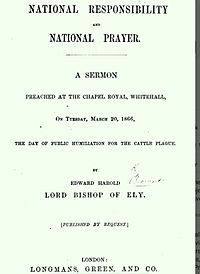

The Great Cattle Plague of 1865

The cattle plague of 1865-1867 was a huge disaster for farming in the 1800s. People didn't know much about diseases then. Some even thought it was a punishment from God!

It took two years to get rid of the plague. There was no understanding of the germ theory of disease yet. To stop the spread, sick animals were killed, and healthy ones were kept separate. This made people angry about the foreign cattle trade.

New laws were made after the plague. They encouraged the City of London to open a second market just for imported animals. This new market was the Foreign Cattle Market. It was meant to stop not only rinderpest but also other diseases like pleuro-pneumonia and foot-and-mouth disease.

The government could "schedule" (or put on a watchlist) countries that weren't disease-free. Animals from these countries had to land at the new Deptford market. They couldn't go anywhere else. They had to be kept in quarantine and slaughtered within 10 days.

Building the Deptford Market

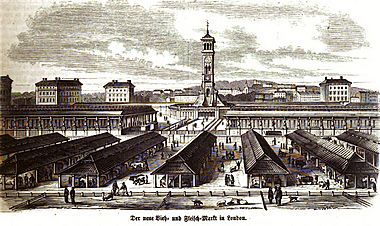

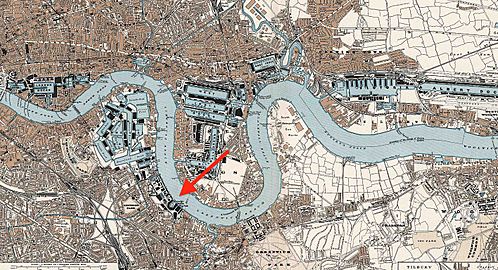

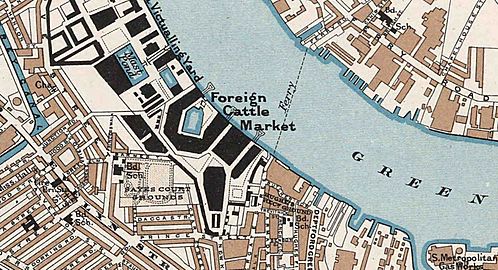

Since the new market had to be in a port, a good spot on the Thames was needed. The old royal dockyard at Deptford was chosen. This was a historic place where Elizabeth I had knighted Francis Drake. Even Peter the Great of Russia had studied shipbuilding here!

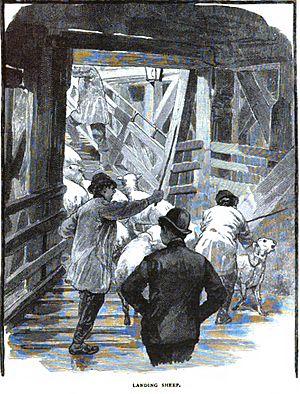

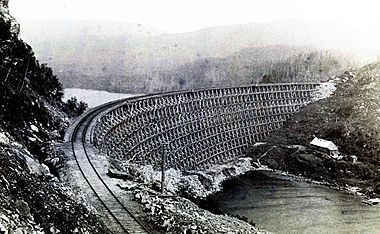

The Deptford site was about 22 acres, later growing to 30 acres. It had a long riverfront. The market was designed to handle up to three cattle boats at once, day or night. Three strong wooden piers were built for unloading animals. These piers had platforms at two levels, so animals could get off no matter how high or low the tide was.

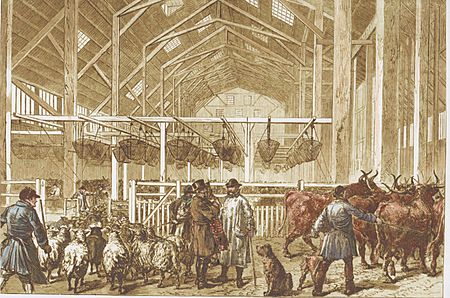

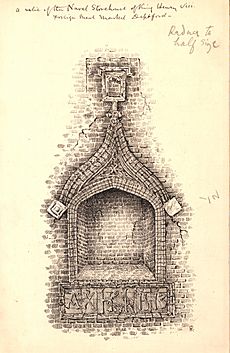

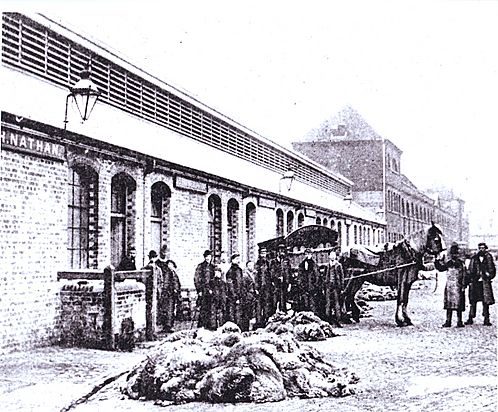

The architect was Sir Horace Jones, who also designed Smithfield Market. He used the existing dockyard buildings. Old shipbuilding sheds were turned into large animal holding areas, called lairages. These areas had water troughs and hay racks. They were lit at night by gas lamps.

The market could hold 5,000 cattle and 14,000 sheep at first. Later, it was made bigger to hold 8,500 cattle and 20,000 sheep. Old navy warehouses became the 70 slaughterhouses.

Some old parts of the dockyard were saved. A sign was put up saying: "Here worked as a ship-carpenter Peter, Czar of all the Russias, afterwards Peter the Great, 1698."

The market opened in January 1872. By 1880, most foreign cattle and sheep imported into the UK were slaughtered at Deptford.

Life at the Market

The market was surrounded by a tall wall. Inside, it had banks, a post office, and its own pub called The Peter the Great.

Trading Animals

This wasn't an auction market. Animals were sold through private deals. Exporters sent their animals to salesmen who worked for a fee. Salesmen and buyers walked around the animal pens. Market days were Mondays and Thursdays. But animals could also be sold on other days, especially when a ship arrived late.

Buyers were usually butchers who rented slaughterhouse space at the market. Slaughtermen, who were paid for each animal they killed, prepared the meat. The buyers then took the meat, hides, and other parts away. Most of the meat was resold at Smithfield Market. By 1887, about 9.4 million animals had arrived at Deptford.

The number of animals traded changed a lot. But by 1890, more foreign cattle came to Deptford than British cattle went to Islington. By 1907, 78% of London's live cattle trade went to Deptford. In 1897, the most cattle landed in one year was 224,831. For sheep, it was 783,440 in 1882.

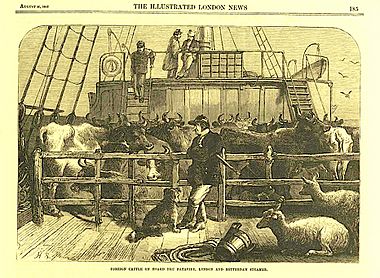

Cattle Boats

Cattle boats from Europe arrived on Sundays and Wednesdays. Over a thousand came each year.

As the trade with America grew, large ocean-going ships were used. These big ships didn't like to dock directly at Deptford. So, the market bought three smaller paddle steamers named Racoon, Taurus, and Claude Hamilton. Animals were transferred to these smaller boats at Gravesend and then brought to Deptford. These three boats carried over 1.6 million animals to the market.

Keeping Animals Healthy

When animals arrived, a vet checked their pulse and temperature. Any animal that seemed sick was watched closely. If one animal in a shipment had a contagious disease, it was killed right away. Its body was sterilised with steam. Other animals from that shipment were also watched.

Workers who handled the animals wore special protective clothes. These were disinfected afterwards. Hides, horns, and other parts were also disinfected. Manure was sterilised. A reporter from The Times newspaper said the market was very clean. He also said animals were killed humanely for that time.

Vets from other countries came to observe. American cattle had ear tags. If a tagged animal was sick, the American vet would send its number to the US government. This helped trace the animal's home farm quickly and stop disease spread. Argentina also sent a vet.

Even with strict rules, diseases sometimes escaped. The government admitted that cattle plague (1877) and foot-and-mouth disease (1880 and 1882) got out of Deptford market.

George Philcox, the Market Boss

The City of London chose George Philcox, a 28-year-old station master, to run the market. He was in charge for 40 years. When he died in 1912, the market soon closed. People said he was a very good and popular boss. They believed "The market made him, and in turn he made it."

Workers at the Market

A social researcher named Charles Booth studied the working conditions at Deptford Market.

The market had about 110 regular employees. But there were also about 1,500 casual workers, mostly drovers and slaughtermen. They were paid for each animal they handled. They could earn good money sometimes, but their hours were irregular. This was because their work depended on when ships arrived. Their jobs were also uncertain because animal disease rules kept changing.

Drovers

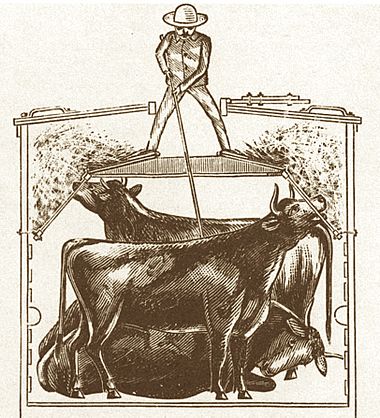

Drovers were the people who moved the animals. They drove them off the boats or transferred them from the big ocean ships at Gravesend.

George Philcox said drovers were paid a set amount per ship. They could unload a cattle boat in just 15 minutes! Some cattle, especially from Argentina, were very wild. A regular drover could earn about £4 a week, which was good pay back then.

Slaughtermen

These men killed and butchered the animals. They worked in teams of four. They earned very high wages for that time, sometimes £5 a week. They didn't work on Saturdays. On other days, their hours varied, sometimes working up to 20 hours straight for urgent orders.

Animals were usually stunned with a blow to the head using a poleaxe. While The Times said Deptford was humane, it wasn't always perfect. Some animals needed more than one blow to be stunned. The Jewish shechita method (a specific way of slaughtering) was also used at the market.

The "Gut Girls"

Around 1891, men who cleaned animal guts went on strike for more pay. The market then gave this work to women.

About 80-100 women and girls, aged 14 to 40, worked daily. They worked for companies that bought all the guts from the slaughterhouses. A "Lady Visitor" writing for the Daily Telegraph said the smell was terrible. Men would roughly remove fat from the guts. Then, the women would turn the guts inside out and wash them with powerful water hoses for sausage makers. In winter, the water was freezing cold.

These women earned about 12 to 14 shillings a week, which was good pay for women's work at the time.

Queen Victoria became interested in the Deptford market. She asked her daughter-in-law, the Duchess of Albany, to check on the girls' working conditions. The Duchess visited, was shocked by what she saw, and complained. It turned out the gut firms were bringing in guts from outside the market, which was a health risk. The City banned this practice. As a result, the women lost their jobs. A charity called the Deptford Fund was started to help them. The play The Gut Girls by Sarah Daniels is a story based on this event.

Deptford: A Global Meat Market

The Deptford Foreign Cattle Market was much more than just buildings. It was a hub for trade that reached farmers and ranchers all over the world. London was known as the biggest meat market globally. The British loved beef and had the money to buy it from anywhere.

From Europe

Early Days

London's demand for meat was so strong that it pulled animals from all over Europe. Some cattle came from Spain, described as "beautiful chestnut brown."

Some animals came from even further, like Kronstadt in Russia. These animals might have traveled from deep inside Russia to reach the market in Saint Petersburg before being shipped to Deptford. However, in 1872, Russia was put on a blacklist because of cattle plague. After that, no more Russian cattle could be landed, even at Deptford.

End of European Trade

The trade in European livestock slowly stopped by the late 1880s. This was because British officials realized that too many animals were coming from places where diseases were common. For example, even though Prussia had strict laws, cattle were smuggled from Poland.

By then, the United States had become the main supplier of animals to Deptford.

From the United States

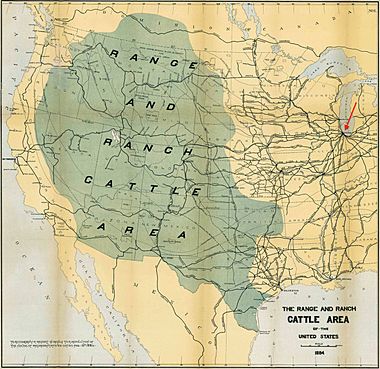

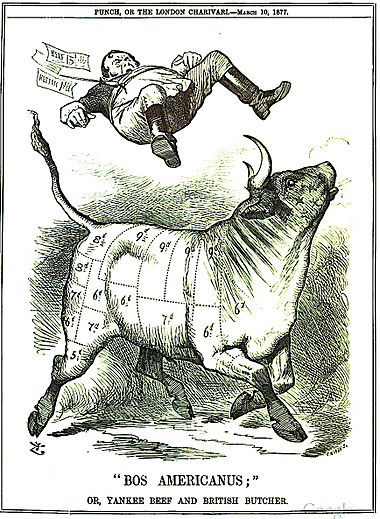

Most of the cattle that came to Deptford Market were from the U.S.A. This started in 1878. By 1913, when Deptford closed, over 3.1 million American cattle had arrived there, along with many sheep and pigs.

Almost all American livestock exports went to England. Americans had more animals than their own country needed. By 1913, Americans needed all the meat their farms produced, so exports stopped.

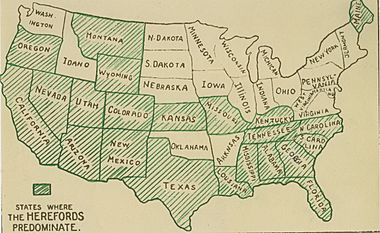

Better Animals in the American West

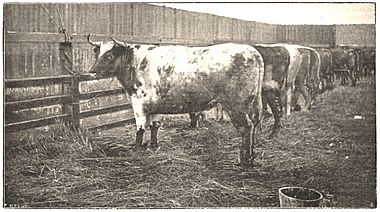

The extra animals came from the new lands in the American West. Early Western cattle, like Texas longhorns, were tough. But it cost the same to ship a tough cow as a high-quality one. So, American shippers started sending their best animals.

At first, only cattle from the East were good enough for export. But Western cattlemen realized they could earn more money by improving their herds. They bought expensive British bulls to make their cattle better. This trade helped improve the quality of American beef.

Long Distances

In 1880, The Times reported that a 1,200-pound steer from places like Colorado or Montana could travel over 2,000 miles by land and 3,000 miles by sea to Deptford. This cost about £10 or £12. This added only a small amount to the price of the meat.

Scientific American reported that five cattle ships sailed from New York to England in one day. These cattle mainly came from states like Ohio, Kentucky, and Illinois. Some even came from as far as Oregon.

Impact on the American West

The cattle trade to England had a big impact on the American livestock industry. London was the most important market. The trade helped improve the quality of American cattle.

Some British farmers even started their own ranches in America. By 1884, it was thought that one-sixth of all American herds were owned by Englishmen. British investors also helped develop the American West.

From Canada

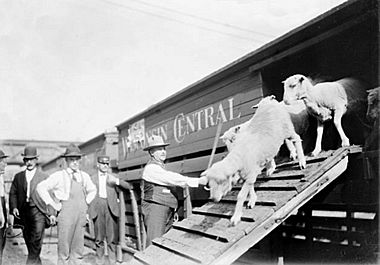

Canada also had a big export industry. Cattle from Alberta and Assiniboia traveled east on the Canadian Pacific Railway. The St. Lawrence River route meant a calm and cool start to the sea journey. For many years, Canadian livestock was considered disease-free. But from 1892, they also had to be slaughtered at Deptford. Exports grew but then decreased after a harsh winter.

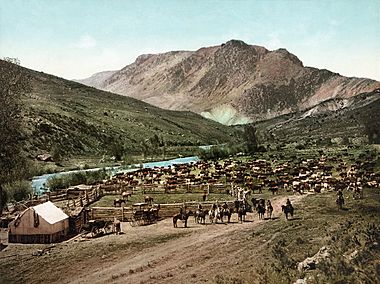

From Argentina

As American cattle supplies decreased, Deptford's main source became Argentina. Argentine cattle used to be of lower quality, mainly used for hides and bones. But selective breeding and alfalfa (a type of plant for feed) changed this.

From about 1888, live cattle and sheep were shipped from Buenos Aires. Carpenters built temporary stalls on the ship decks. Animals were brought to Buenos Aires by train and lifted onto ships by cranes. The journey to London took about 30 days. Argentine cattlemen paid high prices for good bulls to improve their herds. Wild animals didn't do well on the long sea journey, so they had to be tamed first.

Deptford was closed to Argentine cattle in 1900 due to foot-and-mouth disease. It briefly reopened in 1903. After that, it made more sense to ship chilled meat, which was better and easier. This caused high unemployment in Deptford.

From Australia and New Zealand

Towards the end of the 1800s, cattle and sheep were even shipped to Deptford from Australia and New Zealand.

The first commercial shipment from Sydney took 67 days, going around Cape Horn to avoid the heat of the Suez Canal. These cattle arrived in 1894 but were sold at a loss. The next year, a shipment from Port Pirie was much more successful. Another success was 250 sheep from New Zealand.

However, many animals were lost on these very long journeys. Out of 2,654 cattle shipped from Australia/New Zealand, 607 were lost. Out of 3,882 sheep, 57 were lost.

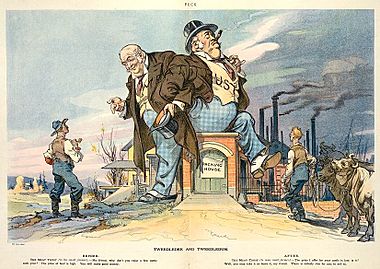

The Beef Trust

The Beef Trust was a group of large meat companies in Chicago. They worked together to control meat prices in the United States. They were so powerful that President Theodore Roosevelt tried to break them up. By 1900, the Beef Trust controlled the shipping of live cattle from America to England.

Newspapers claimed that the Trust bought many shops in Smithfield Market. They met every morning to set the price of British beef. They also controlled the animal holding areas at Deptford Market. Instead of selling their Deptford cattle to buyers at the market, they sent the meat directly to Smithfield. This meant that many market days at Deptford were canceled because there were no buyers.

A Member of Parliament, C. W. Bowerman, asked many questions about this. So, Winston Churchill, who was in charge of trade, started an investigation in 1909. The investigation found that the claims were mostly true. The Trust did control the meat trade across the Atlantic. However, they weren't powerful enough to set all meat prices in the UK. This was because American beef exports had gone down, and lots of chilled beef was coming from Argentina.

Animal Journeys and Welfare

Animals traveled from farms all over the world to be slaughtered at Deptford. Even today, animals can get stressed or injured during transport. In the past, when animals were wilder, it was even harder.

In the Victorian era, there was a lot of talk about how bad conditions were on transatlantic cattle ships. Before crossing the Atlantic, most animals had already traveled for a week or more on cattle trains. Some said the train journeys were as bad, if not worse, than the sea voyages.

Transatlantic Cattle Ships

American cattle usually sailed from New York, Boston, or Philadelphia. Canadian cattle shipped from Montreal, and Argentine cattle from Buenos Aires.

Early Problems

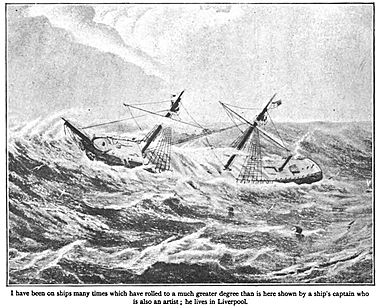

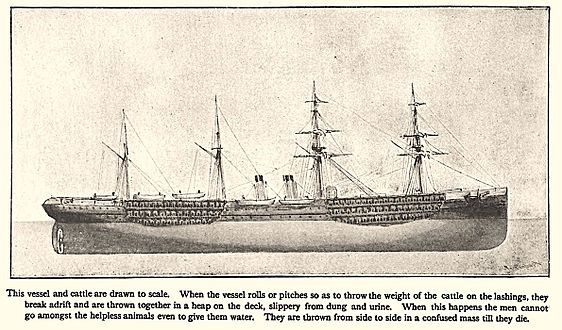

Shipping cattle safely across the Atlantic needed good planning, which was often missing in the early days. Conditions were "very bad," sometimes compared to the "middle passage" of slave trading ships. The worst ships were "tramp steamers," which weren't built for cattle. They were quickly set up with temporary decks and packed tightly with animals.

Winter was the most dangerous time. Insurance costs soared because a bad storm could mean throwing all the cattle overboard to save the ship.

In 1879, the chief vet reported "terrible" losses. Over 10,000 animals were thrown overboard, 1,210 arrived dead, and 718 were so badly injured they had to be killed on arrival.

Samuel Plimsoll's Campaign

In 1890, Samuel Plimsoll, famous for making ships safer with the Plimsoll line, started campaigning against the transatlantic cattle trade. He said it should be stopped.

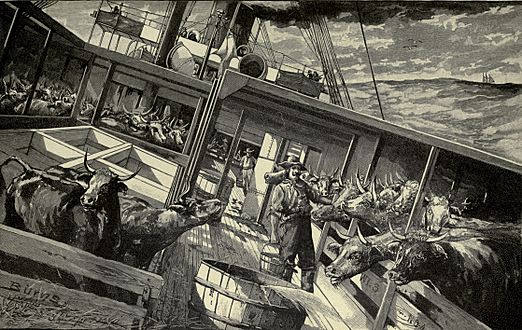

Plimsoll argued that cattle ships were dangerous and cruel. They were unstable if animals were carried on upper decks. Animals were washed overboard or thrown off to save the ship. If kept below deck, they could suffocate if hatches were closed in bad weather. Animals stood in their own waste, which was slippery, causing them to fall and get injured.

Plimsoll also claimed that workers weren't allowed to humanely kill badly injured animals. This was because insurance companies supposedly wouldn't pay. He also said workers used cruel methods to make animals stand up, like piercing them with pitchforks or beating them. Cattle shippers denied this, saying they had nothing to gain from such cruelty.

The workers who looked after the cattle were called "cowboys of the seas." Some were experienced, strong men. Others were poor men who worked for little or no pay just to get across the Atlantic. The poet W.H. Davies was one of these workers and wrote about the harsh methods used to make cattle stand. This was done to stop animals from getting tangled or being trampled.

Improvements

A government investigation confirmed many of Plimsoll's claims. While he didn't stop the trade, new rules banned some of the worst practices.

Later, the trade was controlled by four large American meat companies, part of the "Beef Trust." They didn't own ships but set up a regular shipping system. This meant animals arrived on time and in better condition. By 1892, animal losses on the North Atlantic route were less than 1%.

Even on good ships, dung and urine built up in the holds. The smell was terrible. The journey from New York to the Thames took about 11 days. Cattle could smell land when they were still far away and would sometimes bellow loudly.

Cattle Trains

From the cattle-raising areas, animals were taken by train to markets, mostly to Chicago. Chicago had a special market for "export grade" cattle. These were then sent by train to ports on the East Coast for shipment to England. The map also shows the Canadian Pacific Railway, which carried livestock from the Rocky Mountains to Montreal.

Long Journeys

A U.S. law from 1873 said animals shouldn't travel more than 28 hours by train. After that, they had to be unloaded for water, food, and 5 hours of rest. But often, the railroad companies didn't provide proper food or water. Sometimes, the rest stops were muddy or snowy.

The 28-hour limit was often ignored. Some argued it was better to keep animals on the train than to repeatedly unload and reload them, which could cause more harm. In 1906, the law was changed to allow up to 36 hours of travel if owners agreed.

"Palace" or "parlor" stock cars were special trains meant to provide water and hay. They were allowed to travel for 60 or even 100 hours. But in reality, food and water were rarely supplied.

Overcrowding and Injury

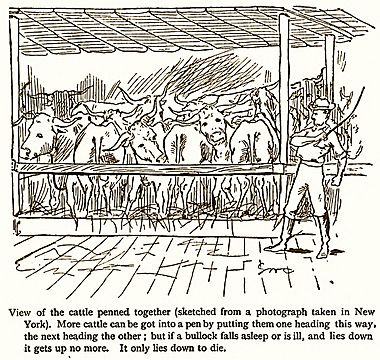

Shipping space was usually sold by the carload. So, there was a reason to pack as many animals as possible to save money. Some thought tight packing was good because it stopped animals from fighting or lying down.

If a cow fell or lay down, it might not get up again. Workers, who traveled in the back of the train, would check on the animals. If they saw a fallen animal, they would try to make it stand up using a special tool called a cattle prod.

One official wrote that "not a train is brought to any great market without having many crippled [cows], and several dead ones."

In Canada, there was no 28-hour law, and train journeys were very long. This meant Canadian cattle often arrived in Britain looking "gaunt and shrunken."

Was the Live Cattle Trade Needed?

Plimsoll's Argument

Samuel Plimsoll believed the transatlantic live cattle trade was not needed. He thought it only helped dishonest traders.

Chilled Meat: An Alternative

Imported Dead vs. Alive

An alternative to live cattle was American chilled meat. It was already being imported in 1875 and was a success. It was much cheaper to send chilled meat across the Atlantic than live animals. Chilled meat took up less space, and only the edible parts were shipped.

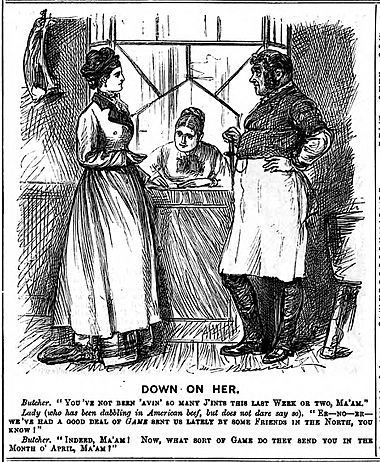

Also, butchers could easily tell if meat was American if it was imported dead. This was because American butchers cut meat differently. Chilling also slightly changed the meat's color. But American meat killed at Deptford was cut by British butchers, so it looked just like British meat.

Why the Price Difference?

At Smithfield Market, American beef killed at Deptford sold for 10-15% more than the same amount of American chilled beef. Was this because it was better, or because it could be sold as British meat? This was a big debate. British farmers believed butchers were cheating. Butchers said farmers just wanted to protect themselves from competition.

Plimsoll argued that chilled meat was as good as, or even better than, Deptford-killed beef. He said chilling was like aging meat properly. Animals slaughtered at Deptford were often tired, stressed, and bruised from their long journeys.

It's hard to know what people really thought of chilled beef. Taste, prejudice, and snobbery played a part. By the early 1900s, some authors said wealthy people bought high-quality chilled beef. Plimsoll believed customers should be able to choose and know what they were buying.

Another Idea

One historian, Richard Perren, suggested that the live meat trade lasted because the chilled meat trade was riskier. Chilled meat had to be sold quickly once it arrived. Live animals could wait a bit longer. However, he also noted that chilled meat could last longer once cold storage was available. He agreed that some butchers cheated by selling Deptford-killed meat as English.

Cheating Was Easy

If cheating happened, it was easy to do. There were no strong laws to mark where meat came from until 1933. Plimsoll calculated that this fraud was worth a lot of money. But these gains decreased over time.

For example, it was reported that "foreign merino sheep" were slaughtered at Deptford, sent to Cardiff, then their hindquarters were sent back to London and sold as Welsh mutton. A writer for a Chicago magazine in 1912 couldn't find any American meat for sale at Smithfield, even though he knew American cattle had been killed at Deptford. Finally, a stallholder admitted their meat was being sold as English.

An Unexpected Benefit

Surprisingly, the transatlantic cattle trade made bread cheaper! Here's why:

Ships carrying cattle were too light when empty. They needed heavy material, called ballast, to make them stable. An easy way to do this was to fill their deep holds with American grain. On some routes, the grain was carried for free because it was cheaper than buying other ballast. So, cheap American wheat came to England at very low prices. This meant that people who ate beef were actually helping to make bread cheaper for everyone!

The End of the Foreign Cattle Market

After 1903, Argentina stopped sending cattle, and American and Canadian supplies decreased. The market started to decline. In 1912, George Philcox, the market's superintendent, died. People said he died of a broken heart because the market he loved was fading away. In 1913, the City of London decided to close it.

When World War I started, the War Office took over the site. It became a supply base, sending food to soldiers in France. After the war, the City sold the site to the government. Today, the area is known as Convoys Wharf.

Some parts of the old Market and dockyard, like boundary walls, are still standing today and are protected as historic buildings.

|

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |