Fort Loudoun (Tennessee) facts for kids

|

Fort Loudoun

|

|

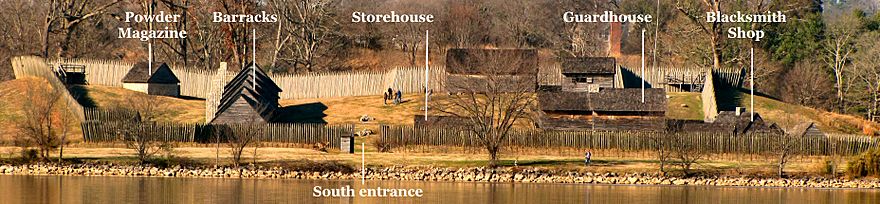

A modern reconstruction of Fort Loudoun.

|

|

| Location | Vonore, Tennessee, South bank of Little Tennessee River, about 3/4 miles southeast of U.S. 411 |

|---|---|

| Area | 50 acres (200,000 m2) |

| Built | 1756–1757 |

| Architect | John William G. De Brahm |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000729 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | June 23, 1965 |

Fort Loudoun was a fort built by the British in what is now Monroe County, Tennessee. It was built between 1756 and 1757 during the French and Indian War. The British hoped the fort would help them become allies with the Cherokee people. It was one of the first major British forts built west of the Appalachian Mountains.

At first, the British soldiers and the local Cherokee had a friendly relationship. But things turned sour in 1758 after fighting broke out between Cherokee warriors and American settlers in Virginia and South Carolina. In 1760, the Cherokee surrounded Fort Loudoun, starting a siege.

The soldiers inside the fort ran out of supplies and had to surrender in August 1760. As the soldiers were leaving, they were attacked by some Cherokee warriors. More than two dozen soldiers were killed, and most of the survivors were taken prisoner.

The fort was rebuilt in the 1930s based on old plans and drawings. In 1965, it was named a National Historic Landmark. Today, it is the main attraction of Fort Loudoun State Historic Park.

Contents

Why Was the Fort Built?

A Plan for Trade and Control

As early as 1708, the British wanted to build a fort in Cherokee territory. They believed a fort would help them control trade with the Cherokee. The Cherokee lived in the mountains, and it was hard for the British to regulate the trade from far away.

Support for the fort grew during King George's War (1744–1748). The British were worried that the French, their main rivals in North America, would gain too much power in the area. The Overhill Cherokee, who lived on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains, asked South Carolina to build a fort in 1747. They needed protection from other tribes who were allied with the French.

The French and Indian War

When the French and Indian War started in 1754, the British became very interested in building the fort again. The Cherokee were allies of the British, but some had started to support the French.

The British government gave money to the governor of Virginia to build a fort. In return for the fort, which would protect their families, the Cherokee agreed to send 600 warriors to help the British fight.

Building Fort Loudoun

The plan was for Virginia and South Carolina to build the fort together. But the Virginians, led by Major Andrew Lewis, arrived first in June 1756. They built a small fort called the "Virginia Fort" and then went home.

The main group of soldiers from South Carolina arrived on October 1, 1756. This group included 80 British soldiers and 120 colonial troops. They also had to move heavy cannons over the mountains, which was a very difficult job.

Designing the Fort

The fort was designed by John William Gerard de Brahm, a German engineer. He and the fort's commander, Captain Raymond Demeré, argued about where to build it. They finally agreed on a spot on a hill near the Little Tennessee River.

Construction began on October 5, 1756. De Brahm's design was complex.

- It was shaped like a diamond with four points called bastions.

- Each bastion had three cannons.

- The walls were 300 feet long.

- A deep ditch, or trench, was dug around the fort.

De Brahm left in December 1756, even though the fort was not finished. After he left, Captain Demeré made the walls simpler but stronger. The fort was officially completed on May 30, 1757. It was named for the Earl of Loudoun, the commander of all British forces in North America.

Life at the Fort

In August 1757, Captain Raymond Demeré was replaced by his brother, Paul Demeré. By 1758, the fort had a guardhouse, storage buildings, a well, and a house for the commander. The soldiers also planted 700 acres of crops.

Life was usually calm. Guards were on duty day and night, and guard dogs roamed outside the walls. The fort's blacksmith was busy fixing Cherokee guns and tools. Soldiers got food by hunting, fishing, and farming. Some soldiers even had Cherokee wives, and about 60 women and children lived inside the fort.

The soldiers and the Cherokee worked together. In 1757, soldiers helped the Cherokee fight off an enemy attack. The fort's commander also encouraged the Cherokee to attack the French.

The Anglo-Cherokee War

The good relationship between the British and the Cherokee started to fall apart in late 1758. Some Cherokee warriors, who were helping the British, attacked settlers in Virginia. In return, settlers killed several Cherokee, and the violence grew.

Fearing a war, the governor of South Carolina, William Lyttelton, stopped selling guns to the Cherokee in August 1759. This made some Cherokee turn to the French for weapons.

In October 1759, a group of Cherokee leaders, including Oconostota, went to Charleston to ask for peace. But Governor Lyttelton did not trust them and took them prisoner. He later made a peace treaty with another chief, Attakullakulla, but kept most of the Cherokee leaders as hostages at Fort Prince George.

In February 1760, Oconostota tried to free the hostages. He set up an ambush and the commander of Fort Prince George was killed. In the confusion that followed, the soldiers inside the fort killed all the remaining hostages.

The Siege of Fort Loudoun

The killings at Fort Prince George made the Cherokee very angry. On March 20, 1760, Cherokee warriors led by Standing Turkey and Willenawah attacked Fort Loudoun. The fort's cannons kept them from getting too close, so they decided to surround the fort and wait. This is called a siege.

The soldiers inside the fort slowly ran out of food. By July, they were eating horse meat. The men were miserable, and some started to desert. On August 6, the officers decided they could not hold out any longer. They met with Cherokee leaders and agreed to surrender. The Cherokee would get the fort and its cannons, and the soldiers would be allowed to leave safely.

The Attack at Cane Creek

The soldiers left the fort on August 9, 1760. The next morning, while they were camped by Cane Creek, about 700 Cherokee warriors attacked them.

In the fight, three officers, 23 soldiers, and three women were killed. The commander, Paul Demeré, was executed. The only officer who survived was John Stuart, who was saved by his friend, the chief Attakullakulla. The rest of the soldiers and their families were taken captive but most were later ransomed.

After the Fort Fell

In 1761, the British sent an army that destroyed several Cherokee towns. The Cherokee then signed a peace treaty. A peace mission was sent to the Overhill Cherokee towns, and a soldier named Henry Timberlake wrote in his journal that Fort Loudoun was in ruins.

Over the years, the fort crumbled away. By the late 1800s, almost nothing was left except for the well. In 1917, a historical group placed a marker at the site.

Rebuilding the Fort

In 1935, a project began to rebuild Fort Loudoun. Archaeologists dug at the site to find the exact locations of the walls, buildings, and other features. They used old maps and letters to make the reconstruction as accurate as possible.

In the 1960s, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) planned to build Tellico Dam, which would flood the site of the fort. After many arguments, the TVA agreed to help save the fort. They moved tons of earth to raise the ground level by 26 feet (8 meters).

The fort was then carefully rebuilt on top of this raised land. The palisade walls, powder magazine, blacksmith shop, and barracks were all reconstructed.

The Fort Today

Today, Fort Loudoun is the center of Fort Loudoun State Historic Park. The fort sits on an island in Tellico Lake. A visitor center next to the fort has a museum with artifacts found during the excavations.

Near the fort is the Sequoyah Birthplace Museum. Sequoyah, who created the Cherokee writing system, was born in the village of Tuskegee, which was located near the fort. There are also monuments to the important Cherokee towns of Tanasi and Chota nearby.

See also