Fredrika Bremer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Fredrika Bremer

|

|

|---|---|

Copy of a portrait by Johan Gustaf Sandberg

|

|

| Born | 17 August 1801 |

| Died | 31 December 1865 (aged 64) |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Known for | Writer, feminist |

|

Notable work

|

Hertha |

Fredrika Bremer (born August 17, 1801 – died December 31, 1865) was an important Swedish writer and a champion for women's rights. She was born in Finland, which was then part of Sweden. Her books, especially Sketches of Everyday Life, became very popular in Britain and the United States in the 1840s and 1850s. Many people called her the "Swedish Jane Austen" because she helped make realistic novels popular in Sweden.

When she was in her late 30s, Fredrika asked King Charles XIV to make her legally independent from her brother. This was a big step for women at the time. Later, in her 50s, her novel Hertha started a social movement. This movement led to a new law that gave all unmarried Swedish women legal independence at age 25. It also helped create Högre Lärarinneseminariet, which was Sweden's first college for women. Her work also inspired Sophie Adlersparre to start Home Review, Sweden's first magazine for women. In 1884, the first women's rights group in Sweden, the Fredrika Bremer Association, was named after her.

Growing Up in Sweden

Fredrika Bremer was born on August 17, 1801. Her family was Swedish-speaking and lived in Finland, near Turku. She was the second of seven children. Her grandparents had built a large business empire in Finland. But her father sold off their businesses. When Fredrika was three, her family moved to Stockholm, Sweden. A year later, they bought Årsta Castle, which was about 20 miles from the capital. Fredrika spent her summers there and her winters in Stockholm.

Fredrika and her sisters were raised to be socialites. They were expected to marry well and host parties, just like their mother. They received a typical education for girls of their class. They had private tutors and traveled through Germany, Switzerland, France, and the Netherlands. Fredrika was good at painting tiny pictures and learned French, English, and German.

She felt that the life expected of Swedish women was very limiting. Her own education was strict, with a tight schedule for her days. She described her family life as being "under the oppression of a male iron hand." In Stockholm, the girls were not allowed to play outside. They exercised by jumping up and down while holding onto chairs. Fredrika wrote French poems when she was only eight. She was seen as awkward and rebellious as a child. One of her sisters even wrote about how Fredrika enjoyed cutting up dresses and curtains and throwing things into the fire.

Finding Her Path

After returning to Sweden, Fredrika joined high society in Stockholm. But she found the passive life for women unbearable. She felt like time stood still for her. She was deeply moved by the poems of Schiller. She began to wish for a career where she could do good in the world. She wrote that she felt numb from embroidering, and her desire to live was fading. This feeling led to a period of sadness. She wanted to work at a hospital in Stockholm, but her sister stopped her. However, she found great joy in helping people around her family's estate in Årsta during the winters of 1826 and 1827.

Her charity work led her to start writing. She began writing in 1828, hoping to earn money for her charity work. Her four-volume series, Sketches of Everyday Life, was published anonymously from 1828 to 1831. It was an instant success, especially the funny story Family H—. She felt that writing was a revelation, like "champagne bubbles out of a bottle." The Swedish Academy gave her a gold medal in 1831. She continued to write for the rest of her life.

Her success made her want to study literature and philosophy more deeply. A friend introduced her to the ideas of Jeremy Bentham, which changed her political views. Bentham's idea of "the greatest happiness to the greatest number" encouraged her to keep writing. In 1831, she started taking lessons from Per Johan Böklin, a teacher. They became very close. She wrote that she wanted to "kiss a man, breastfeed a baby, manage a household, to be happy." But she did not accept Böklin's marriage proposal. He married another woman in 1835. Fredrika never married. They remained close friends and wrote letters to each other for the rest of their lives.

Her novel The President's Daughters (1834) showed her growing maturity. It humorously showed a young woman becoming more open and friendly. Its sequel, Nina (1835), was not as successful.

A Successful Writer and Traveler

For the next five years, Fredrika stayed with her friend Countess Stina Sommerheilm in Norway. She had thought about working as a nurse, but instead focused on her writing. During this time, the countess's stories inspired Fredrika's famous book The Neighbors (1837). Her next novel, The Home (1839), was influenced by writers like Goethe. Her play The Thrall (1840) explored the lives of women during the Viking Age. After the countess died, Fredrika returned to Stockholm in 1840.

After her father died in 1830, Fredrika became closer to her mother. However, under Swedish law, all unmarried women were considered minors. They were under the care of their closest male relative. Fredrika and her unmarried sister Agathe were under the care of their older brother. He had wasted the family's money. To change this, they had to ask the King directly. Their request was approved, and they became legally independent.

Fredrika spent the winter of 1841–42 alone at Årsta Castle. She wrote Morning Watches (1842), where she shared her personal religious beliefs. This caused some debate, but she had support from other writers. This book was also the first one she signed with her full name, making her a literary star. In 1844, the Swedish Academy gave her another gold medal.

In 1842, Fredrika returned to Swedish social life. She wrote about it in her Diary the next year. She was described as "dreadfully plain" but was known for being humble, loyal, energetic, and strong-willed. She did not care much for money or possessions. She once said that nothing valuable would be happy with her. Another writer, Geijer, joked that if she could push everyone into heaven, she wouldn't mind staying outside herself.

Fredrika began traveling, first around Sweden, then abroad. Her books were translated into German and English. They became even more popular in England and the United States than they were in Sweden. This meant she received warm welcomes wherever she went. After each trip, she published successful books about the places she visited. Her trip to Germany in 1846 led to books like A Few Leaves from the Banks of the Rhine (1848).

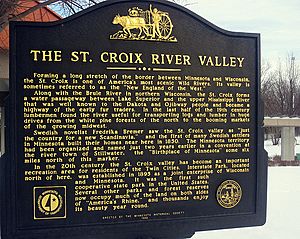

Travels and Social Work

Inspired by other writers, Fredrika visited and traveled widely through the United States. She left Copenhagen on September 11, 1849, and arrived in New York on October 4. She wanted to study how democratic ideas affected society, especially for women. She visited Boston and New England, where she met famous writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. She also visited Shaker and Quaker communities. She traveled to the South to see the conditions of enslaved people. She also went to the Midwest to visit Scandinavian communities and Native Americans. Like Alexis de Tocqueville before her, she visited American prisons and spoke with prisoners. She then visited Spanish Cuba before returning to New York. She left for Europe on September 13, 1851.

During her journey, she wrote many letters to her sister Agathe. These letters were later published as her two-volume book Homes in the New World (1853). She had previously described the Swedish home as a world in itself. Now, she described America as a big home, thanks to the many families who hosted her. She spent six weeks in Britain, visiting cities like Liverpool and London. She met writers like Elizabeth Gaskell. Her articles about England for the Aftonbladet newspaper mostly praised the Great Exhibition, which she visited four times. These articles were later collected into a book called England in 1851.

After returning to Sweden in November, Fredrika tried to get Swedish women involved in social work. She had seen similar efforts in America and England. She helped start the Stockholm Women's Society for Children's Care. This group helped orphans after a cholera outbreak in 1853. She also co-founded the Women's Society for the Betterment of Prisoners in 1854. This group aimed to help female prisoners. In 1854, during the Crimean War, her "Invitation to a Peace Alliance" was published in the London Times. It was a call for Christian women to promote peace.

Fighting for Women's Rights

In 1856, Fredrika published her novel Hertha. This book strongly criticized the laws that treated unmarried adult women as second-class citizens. The book sparked a big discussion in Sweden called the "Hertha Discussion." This discussion reached the Swedish Parliament in 1858. As a result, the old law was changed. Unmarried women could now ask their local court to become legally independent at age 25. Five years later, the law was changed again. All unmarried women automatically became legally independent at age 25. This change did not affect married women, who were still under their husbands' care.

The novel Hertha also raised the idea of a "women's university." This led to the opening of Högre Lärarinneseminariet in 1861. This was a state school for training female teachers. Fredrika was not in Sweden during the "Hertha Discussion." From 1856 to 1861, she was on another long journey through Europe and the Middle East. She visited Switzerland, Brussels, and Paris. She was very interested in Switzerland's new "free church" movement. From 1857, she traveled through Italy, comparing Catholic practices with the Swedish Lutheran Church. Finally, she went to Palestine in 1859. Even though she was almost 60, she explored the places where Jesus Christ lived. She then visited Constantinople and toured Greece from 1859 to 1861. She arrived back in Stockholm on July 4, 1861. Her travel stories were published as Life in the Old World (1860–1862).

When she returned to Sweden, she was happy with the changes Hertha had brought. She took an interest in the new women's college and its students. She continued her charity work and helped with the Home Journal. This was the first women's magazine in Scandinavia, started by Sophie Adlersparre while Fredrika was away. After a final trip to Germany in 1862, she stayed in Sweden for the rest of her life. She was reportedly pleased when the old Swedish Parliament was abolished and when slavery was ended in the United States. She died at Årsta Castle near Stockholm on December 31, 1865.

Legacy and Impact

Fredrika Bremer's name lives on in several places. The town of Frederika, Iowa and Bremer County, Iowa in the United States are named after her. There is also a Fredrika Bremer Intermediate School in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The American Swedish Historical Museum in Philadelphia has a special room dedicated to her achievements.

Literary Influence

Fredrika Bremer's novels were often romantic stories. They usually featured independent women who observed others dealing with marriage. She believed in a new kind of family life. One that focused less on men and gave more space for women's talents and personalities. Many of her books showed a clear difference between city and country life. Nature was always shown as a place for new beginnings and self-discovery.

By the time Fredrika Bremer revealed her name to the public, her books were a well-known part of Swedish culture. Translations made her even more famous abroad. She was seen as the "Swedish Jane Austen". When she arrived in New York, a newspaper claimed she "probably... has more readers than any other female writer on the globe." They called her the author "of a new style of literature." Fredrika was a literary celebrity. She always had a place to stay during her two years in America, even though she knew no one before she arrived. Writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman praised her. Louisa May Alcott's book Little Women even includes a scene where Mrs. March reads from Bremer's works to her daughters.

However, her popularity abroad peaked in the 1840s and 1850s and faded by the early 1900s. In Sweden, she remained highly respected, but her books were not read as much. The publication of her letters in the 1910s brought new interest from scholars, but mostly in her personal life and travels. By 1948, a Swedish critic wrote that Bremer "really only lives as a name and a symbol." But in the late 20th century, Swedish feminists rediscovered her novels. They are now being studied and appreciated again.

Social Causes and Activism

Fredrika Bremer was deeply interested in politics and social reform. She cared about gender equality and social work. She was an important voice in the debate for women's rights and also a generous helper. She was a liberal thinker who cared about social issues and the working class.

In 1853, she helped start the Stockholm women's fund for child care with Fredrika Limnell. In 1854, she also helped create the Women's Society for the Improvement of Prisoners. This group visited female prisoners to offer support and help them improve through religious studies.

Her novel Hertha (1856) is her most important work. It is a serious novel about how women lacked freedom. It led to the "Hertha debate" in parliament. This debate helped create a new law in 1858 that gave adult unmarried women legal independence in Sweden. This was a starting point for the real feminist movement in Sweden. Hertha also brought up the idea of higher education for women. In 1861, the state founded the University for Women Teachers, Högre lärarinneseminariet, inspired by the women's university suggested in Hertha. In 1859, Sophie Adlersparre started the magazine Tidskrift för hemmet, inspired by the novel. This was the beginning of Adlersparre's work as a leader in the Swedish feminist movement. The women's magazine Hertha, named after the novel, was founded in 1914.

In 1860, she helped Johanna Berglind fund Tysta Skolan, a school for deaf and mute children in Stockholm. In 1862, during reforms about voting rights, she supported giving women the right to vote. Some people thought it would be a "horrific sight" to see women voting. But Bremer supported the idea. That same year, women who were legally independent were given the right to vote in local elections in Sweden. The first real women's rights movement in Sweden, the Fredrika Bremer Association, founded by Sophie Adlersparre in 1884, was named after her. Bremer was always happy to mention and recommend the work of other female professionals. She spoke about the doctor Lovisa Åhrberg and the engraver Sofia Ahlbom in her writings.

Works

- Sketches of Everyday Life (1828–31)

- New Sketches of Everyday Life (1834–58)

- Thrall (1840)

- Morning Watches (1842)

- Life in Sweden. The President's Daughters (1843)

- The Home or Family Cares and Family Joys (1844)

- The H___ Family: Tralinnan; Axel and Anna;; and Other Tales (1844)

- Life in Dalecarlia: The Parsonage of Mora (1845)

- A Few Leaves from the Banks of the Rhine (1848)

- Brothers and Sisters: A Tale of Domestic Life (1848)

- The Neighbors (1848)

- Midsummer Journey: A Pilgrimage (1848)

- Life in the North (1849)

- An Easter Offering (1850)

- Homes in the New World (2 vols. 1853–1854)

- The Midnight Sun: A Pilgrimage (1855)

- Life in the Old World (6 vols. 1860–1862)

- A Little Pilgrimage in the Holy Land (1865)

- England in the Fall of 1851 (published 1922)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Fredrika Bremer para niños

In Spanish: Fredrika Bremer para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |