Grosse Isle facts for kids

|

Native name:

Grosse Île

|

|

|---|---|

| Geography | |

| Location | Gulf of Saint Lawrence |

| Coordinates | 47°02′N 70°40′W / 47.033°N 70.667°W |

| Archipelago | 21-Island Isle-aux-Grues archipelago |

| Area | 7.7 km2 (3.0 sq mi) |

| Length | 4.8 km (2.98 mi) |

| Width | 1.6 km (0.99 mi) |

| Administration | |

|

Canada

|

|

| Province | Quebec |

| Municipality | Saint-Antoine-de-l'Isle-aux-Grues |

| Official name: Grosse Île and the Irish Memorial National Historic Site | |

| Designated: | 1974 |

Grosse Isle (which means "Big Island" in French) is an island in the St. Lawrence River in Quebec, Canada. It's part of a group of 21 islands called the Isle-aux-Grues archipelago. The island is part of the Saint-Antoine-de-l'Isle-aux-Grues municipality.

This island is also known as the Grosse Isle and the Irish Memorial National Historic Site. It was once a special station for immigrants coming to Canada. Many of these immigrants were Irish people escaping a terrible time called the Great Famine (1845–1849).

The Canadian government first set up this station in 1832. It was used to help stop the spread of diseases like cholera that sometimes came with new arrivals. Later, in the mid-1800s, it was reopened for Irish immigrants. Many of them had caught typhus during their long sea journeys. Thousands of Irish people stayed on Grosse Isle for health checks between 1832 and 1848.

It's thought that over 3,000 Irish people died on the island. More than 5,000 are buried in its cemetery. Many others died during their journey across the ocean. Most who passed away on the island had typhus, which spread easily in the crowded conditions of 1847. Grosse Isle is the largest burial place for people who fled the Great Famine outside of Ireland. After Canada became a country in 1867, the station was updated to meet new health and immigration rules.

Grosse Isle is sometimes called Canada's Ellis Island. Ellis Island was another famous immigration center in the United States. From 1832 to 1932, nearly 500,000 Irish immigrants came through Grosse Isle on their way to a new life in Canada.

Contents

Grosse Isle: A Historic Island

The Journey to Grosse Isle

When immigrant ships reached Grosse Isle, they had to prove they were free of disease. Ships with sick people on board had to fly a blue flag. Dr. George Douglas, the main doctor on Grosse Isle, said it was almost impossible to check everyone properly in 1847. This meant many immigrants had to stay on their ships for days.

Robert Whyte wrote a diary about his journey on a "coffin ship" in 1847. He described how Irish passengers on his ship, the Ajax, cleaned the vessel. They hoped to go to the hospital or on to Quebec after their long trip. But the doctor only checked them quickly and didn't return for days.

By mid-summer, doctors were doing very quick checks. They would let people walk past and only look at the tongues of those who seemed sick. Because of this, many people who were secretly ill were allowed to leave. They often became very sick after leaving Grosse Isle.

Whyte wrote about the sad conditions on his ship. People were sick and needed help, but they were left without medicine or clean water. He also saw other ships where conditions were even worse. Passengers were crowded together, and some who had died were left for a long time. In contrast, German immigrants arriving at Grosse Isle were often healthy and well-dressed.

We don't know exactly how many people died at sea. Whyte estimated it was around 5,293. During the ocean crossing, bodies were often put into the sea. But once ships reached Grosse Isle, the dead were kept on board until they could be buried on land.

Even those who didn't get typhus were very weak from the journey. Many had been told they would get food on the ship, but they didn't. This made them even weaker when they arrived.

Life on the Island

Before the big crisis in 1847, sick people went to hospitals. Healthy people stayed in sheds during their quarantine period. But in 1847, the island quickly became too crowded. Tents were set up, but many new arrivals had no shelter at all.

One bishop saw people lying outside, crying for water. Others were inside tents without beds. He saw a child covered in insects, and another child who sat down and then died. Many children lost their parents.

The sheds were dirty and packed with people. Patients lay in bunk beds, and dirt from the top bunk could fall onto the lower one. Sometimes two or three sick people shared one bed. Meals were simple: tea, gruel, or broth three times a day. There was never enough drinking water for everyone.

The sheds were not built for sick people and had no fresh air. New sheds were built without proper toilets. Because there weren't enough staff, sick people sometimes lay in their own waste for days. There weren't enough people to remove those who died during the night. The hospitals also lacked equipment, and sometimes beds were just planks on the ground.

Catholic priests in Quebec helped the immigrants who left the island. Father McMahon was very important in helping the sick and the children who had lost their families.

Brave Helpers and Challenges

There was a serious shortage of doctors and nurses on Grosse Isle. Dr. Douglas tried to hire healthy female passengers as nurses, offering good pay. But no one accepted because they were afraid of getting sick. Nurses had to sleep near the sick and share their food. They often caught the fever themselves.

Prisoners were sometimes released from jail to help with nursing. However, some of them stole from the sick and dying. All the medical staff got sick at some point, and four doctors died from typhus. Ships were not required to carry a doctor, so few arrived as passengers. One doctor from Dublin, Dr. Benson, volunteered to help. He got typhus and died within six days.

More than forty priests and clergymen, both Irish and French Canadian, worked on Grosse Isle. Many of them also became ill. Bishop Power, a chief pastor, died after giving comfort to a dying woman. The Mayor of Montreal, John Easton Mills, also passed away while caring for the sick.

What Happened Next?

Many immigrants who passed the quick health checks at Grosse Isle still got sick later. Some died in the "healthy" camp on the island. In one week in August, 88 people died in this camp.

Dr. Douglas warned officials in Quebec and Montreal that a disease outbreak was coming. Thousands of "healthy" people left Grosse Isle, but many would soon get sick. Immigrants arrived in Montreal weak and helpless. Some crawled because they couldn't walk. Others were found dying on the docks.

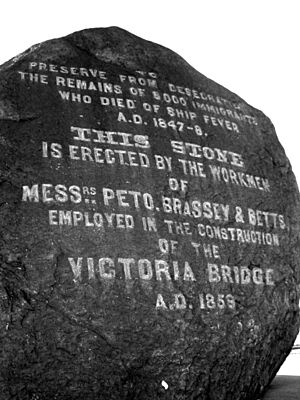

From 1847 to 1848, between 3,000 and 6,000 Irish people died from ship fever in Montreal. Their bodies were found in 1859 by workers building the Victoria Bridge. These workers put up a memorial called the Black Rock. It remembers the 6,000 immigrants who died.

Other cities like Kingston and Toronto also tried to move immigrants through quickly. It's hard to know how many people who survived the journey then died during the harsh Canadian winter. One famous survivor was the grandfather of Henry Ford, who founded the Ford Motor Company.

Remembering the Past

A national memorial, the Celtic Cross, was put up on Grosse Isle on August 15, 1909. It was designed by Jeremiah O'Gallagher. This monument is the largest of its kind in North America. In 1974, the Canadian government made the island a National Historic Site. Another memorial was built on the island in 1997.

A Look Back: Key Dates

Here's a timeline of important events related to Grosse Isle:

- February 1847: Dr. George M. Douglas, the medical officer at Grosse Isle, asked for money to prepare for many Irish immigrants. He received a small amount and permission to hire a boat.

- March 1847: People in Quebec asked the government to prepare for the expected increase in immigrants.

- May 1847: On May 17, the first ship, the Syria, arrived with 430 sick people. Soon, many more ships followed. Dr. Douglas wrote that he had no beds for the sick. By the end of May, 40 ships were waiting, stretching for about 3 kilometers. All of them had sick passengers. Over 1,100 sick people were in sheds, tents, or even the church.

- June 1847: The Catholic archbishop of Quebec asked Irish bishops to tell people not to emigrate. Despite this, most of the 109,000 people heading to British North America were Irish. By June 5, 25,000 Irish immigrants were on Grosse Isle or waiting on ships.

- July 1847: By mid-summer, 2,500 sick people were on Grosse Isle. Dr. Douglas stopped trying to enforce all the quarantine rules because it was impossible. He decided to release healthy passengers after a quick check.

- October 1847: Ice blocked the St. Lawrence River, and immigration stopped for the winter.

In 1847, almost 90,000 Irish immigrants left ports in the United Kingdom. About 5,293 died during the journey. Another 3,452 died at Grosse Isle, and thousands more died in hospitals in Quebec, Kingston, and Toronto. In total, over 15,000 people died. About 17% of all passengers from Ireland died at sea, in quarantine, or in hospitals.

- 1862: 59 people died on the island, with 34 from typhus. Better medical care and faster steamships helped reduce the spread of disease.

- 1870 - 1880: Only 42 deaths were reported on Grosse Isle during this decade.

- 1880 - 1932: Grosse Isle continued to be a quarantine station. It helped stop the spread of diseases like typhus, cholera, beriberi, smallpox, and bubonic plague.

- 1909: The Ancient Order of Hibernians put up a Celtic cross with messages in Irish, English, and French. It remembers those who died in 1847 and 1848.

- 1932: Grosse Isle stopped being a quarantine station. By this time, immigrants were arriving at many different ports, and city hospitals could handle their needs.

- 1956: Agriculture Canada took over the island to quarantine animals.

- 1974: The Canadian government declared Grosse Isle a National Historic Site.

- 1993: Grosse Isle became a national historic park run by Parks Canada.

- 1997: A new memorial was built to honor those who died on the island.

Visiting the Memorial Site

Today, visitors can explore many of the buildings used by immigrants and island workers. The disinfection building shows the original showers and steam cleaning machines. It also has a display about the island's history. You can walk or take a trolley to see the village and hospital area. This includes the 1847 lazaretto (quarantine station), the Catholic and Anglican chapels, and a transport museum.

During certain seasons, actors dress up as islanders. They play roles like quarantine staff, nurses, priests, and teachers. The lazaretto has an exhibit about the sad experiences of the immigrants in 1847.

A walking path leads to the Celtic cross and the Irish Memorial. This memorial honors the immigrants, the quarantine staff, sailors, doctors, and priests who died on the island. On May 25, 1998, Grosse Île and the Irish Memorial National Historic Site became "twinned" with the National Famine Museum in Strokestown, Ireland.

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |