Gustav Heinemann facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gustav Heinemann

|

|

|---|---|

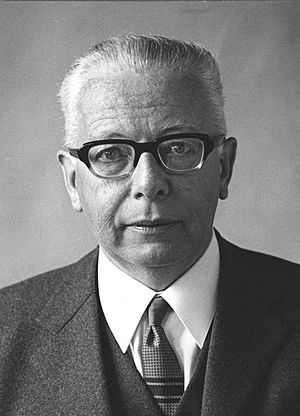

Gustav Heinemann in 1969

|

|

| President of Germany West Germany |

|

| In office 1 July 1969 – 30 June 1974 |

|

| Chancellor | Kurt Georg Kiesinger Willy Brandt Helmut Schmidt |

| Preceded by | Heinrich Lübke |

| Succeeded by | Walter Scheel |

| Minister of Justice | |

| In office 1 December 1966 – 26 March 1969 |

|

| Chancellor | Kurt Georg Kiesinger |

| Preceded by | Richard Jaeger |

| Succeeded by | Horst Ehmke |

| Minister of the Interior | |

| In office 29 September 1949 – 11 October 1950 |

|

| Chancellor | Konrad Adenauer |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Robert Lehr |

| Mayor of Essen | |

| In office 30 October 1946 – 19 October 1949 |

|

| Preceded by | Heinz Renner |

| Succeeded by | Hans Toussaint |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Gustav Walter Heinemann

23 July 1899 Schwelm, Prussia, German Empire |

| Died | 7 July 1976 (aged 76) Essen, West Germany |

| Political party | Christian Social People's Service (1930–1933) Christian Democratic Union (1945–1952) All-German People's Party (1952–1957) Social Democratic Party of Germany (1957–1976) |

| Spouse |

Hilda Ordemann

(m. 1926) |

| Children | 4 |

| Signature | |

Gustav Walter Heinemann (born July 23, 1899 – died July 7, 1976) was an important German politician. He served as the President of West Germany from 1969 to 1974. Before becoming president, he was the mayor of Essen and held several minister positions in the German government.

Contents

Gustav Heinemann's Early Life and Career

Gustav Heinemann was named after his grandfather, who was a master roof tiler. His family had strong beliefs in democracy and freedom. His great-grandfather even took part in the Revolution of 1848. Gustav's father, Otto Heinemann, worked at the Krupp steelworks in Essen and shared these views. From a young age, Gustav felt it was his duty to protect and promote these democratic ideas. He always stood up against people being forced to obey without question. This helped him stay true to his beliefs, even when others disagreed.

After finishing high school in 1917, Heinemann joined the army during the First World War. However, he became very ill and was not sent to the front lines.

Starting in 1918, Heinemann studied law, economics, and history at several universities. He earned his first degree in 1922 and became a lawyer in 1926. He also received two doctorate degrees in law.

Heinemann made many lasting friendships during his university years. His friends included people with different ideas, like Wilhelm Röpke, a leader in economic freedom, and Ernst Lemmer, a trade unionist.

Early in his career, Heinemann joined a well-known law firm in Essen. From 1929 to 1949, he worked as a legal advisor for the Rheinische Stahlwerke, a steel company in Essen. He also became one of its directors in 1936.

The steelworks were vital for the war effort, so Heinemann was not drafted into the army. He also taught law at the University of Cologne from 1933 to 1939. His teaching career likely ended because he refused to join the Nazi Party.

In 1936, Heinemann was invited to join the board of a coal company. But the offer was taken back because he refused to stop working for the anti-Nazi Confessing Church.

Family and His Faith

In 1926, Gustav Heinemann married Hilda Ordemann. She was a student of Rudolf Bultmann, a famous Protestant theologian. Hilda and her local minister, Wilhelm Graeber, helped Heinemann reconnect with his Christian faith. Through his sister-in-law, he met Swiss theologian Karl Barth, who taught him to strongly oppose nationalism and antisemitism.

Gustav and Hilda Heinemann had four children: three daughters named Uta, Christa, and Barbara, and a son named Peter.

Heinemann was a church elder in Wilhelm Graeber's parish in Essen. When Graeber was fired by new church leaders who supported the Nazis in 1933, Heinemann joined the Confessing Church. This group opposed the "German Christians" who cooperated with the Nazis. Heinemann became a member of the Confessing Church's leadership and its legal advisor. Even though he later disagreed with some things in the church leadership, he continued to serve as an elder in his local parish. In this role, he gave legal advice to Christians who were being persecuted and helped Jewish people who were hiding by providing them with food.

Information sheets from the Confessing Church were printed secretly in the basement of Heinemann's house in Essen. These sheets were then sent all over Germany.

From 1936 to 1950, Heinemann was the head of the YMCA in Essen.

In August 1945, he was chosen to be a member of the Council of the Evangelical Church in Germany. In October 1945, this Council issued the Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt. In this declaration, the Protestant church admitted its failure to oppose the Nazis. Heinemann saw this declaration as a very important part of his church work.

From 1949 to 1955, Heinemann was the president of the all-German Synod of Protestant Churches. He also helped start the German Protestant Church Congress, a large meeting for Protestant church members. In 1949, he helped create Die Stimme der Gemeinde ("The Voice of the Congregation"), a magazine published by the Confessing Church. He was also part of the "Commission for International Affairs" in the World Council of Churches.

Early Political Steps

As a student, Heinemann was part of a student group that supported the liberal German Democratic Party. This party strongly believed in the democracy of the Weimar Republic.

In 1920, Heinemann heard Hitler speak in Munich. He had to leave the room after interrupting Hitler's angry speech against Jewish people.

In 1930, Heinemann joined the Christlich-Sozialer Volksdienst ("Christian Social People's Service"). However, in 1933, he voted for the Social Democratic Party to try and stop the Nazi Party from winning.

After World War II

After the Second World War, the British authorities appointed Heinemann as the mayor of Essen. In 1946, he was officially elected to this position and served until 1949. He helped found the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) in North Rhine-Westphalia. He saw the CDU as a democratic group of people from different Christian backgrounds who were against Nazism. He was a member of the North Rhine-Westphalian parliament from 1947 to 1950. From 1947 to 1948, he was also the Minister of Justice in the North Rhine-Westphalian government.

When Konrad Adenauer became the first Chancellor of the new Federal Republic of Germany in 1949, he wanted a Protestant representative in his government. Heinemann, who was president of the Synod of Protestant Churches, reluctantly agreed to become the Minister of the Interior. He had originally planned to go back to working in industry.

A year later, Heinemann resigned from the government. This happened when it became known that Adenauer had secretly offered for Germany to join a Western European army. Heinemann believed that any rearming of West Germany would make it harder for Germany to reunite and would increase the risk of war.

Heinemann left the CDU and, in 1952, started his own political party called the All-German People's Party. Other politicians, like future Federal President Johannes Rau, were members. They wanted Germany to negotiate with the Soviet Union to become a reunited, neutral country. However, Heinemann's party did not get many votes. He closed his party in 1957 and joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Their goals were similar to his own. He quickly became a member of the SPD's national leadership. He helped the SPD become a "party of the people" by welcoming socially-minded Protestants and middle-class people, especially in Germany's industrial areas.

In October 1950, Heinemann returned to working as a lawyer. In court, he mainly represented political and religious minority groups. He also worked to help prisoners in East Germany be released. Later, he defended people who refused to serve in the military for moral reasons and Jehovah's Witnesses in court.

As a member of the Bundestag, West Germany's parliament, Heinemann strongly opposed Adenauer's plans to get atomic weapons for the West German army (the Bundeswehr).

In the government led by Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger (CDU) and Foreign Minister Willy Brandt (SPD), Heinemann served as Minister of Justice from 1966 to 1969. He started many liberal reforms, especially in criminal law.

President of West Germany

In March 1969, Gustav Heinemann was elected President of West Germany. He was elected with the support of most delegates from the Free Democratic Party (FDP). His election showed that the FDP was open to forming a future partnership with the SPD. This led to the "social-liberal coalition" government, which lasted from October 1969 to October 1982.

Heinemann once said in an interview that he wanted to be "the citizens' president" rather than "the president of the state." He started a tradition of inviting ordinary citizens to the president's New Year's receptions. In his speeches, he encouraged West Germans to stop being overly submissive to authorities. He urged them to fully use their democratic rights and to protect the rule of law and social fairness. His open-mindedness towards the student protests of 1968 also made him popular with younger people. When asked if he loved the West German state, he famously replied that he loved his wife, not the state.

As president, Heinemann mainly visited countries that German troops had occupied during World War II. He supported the government's policy of making peace with Eastern European countries. He also promoted research into understanding conflicts and peace, as well as environmental issues.

It was Heinemann's idea to create a museum to remember German liberation movements. He was able to officially open this museum in Rastatt in 1974. His interest in this topic came partly from his own ancestors' involvement in the revolution of 1848.

Because of his age and health, Heinemann did not seek a second term as President in 1974. He passed away in 1976.

Shortly before his death, Heinemann wrote an essay criticizing the Radikalenerlass ("Radicals Decree") of 1972. This rule required all candidates for public service jobs (like teachers or postal workers) to be checked for political extremism. He believed it was unfair to treat a large group of people as suspects, as it went against the spirit of the constitution.

The Gustav-Heinemann-Friedenspreis (Gustav Heinemann Peace Prize) is an annual award for children's and young people's books. It is given to books that best promote world peace.

Awards and Honors

- Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (1969)

- Knight Grand Cross with Grand Cordon of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (1973)

- Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the British Order of the Bath

- Great Star of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria (1973)

- Knight of the Swedish Order of the Seraphim (1970)

- Knight of the Danish Order of the Elephant (1970)

Things Named After Heinemann

- The Gustav-Heinemann-Bürgerpreis (a prize started by the SPD in 1977)

- The Gustav-Heinemann-Friedenspreis für Kinder- und Jugendbücher (Gustav Heinemann Peace Prize for Children's and Youth Books, since 1982)

- The Gustav Heinemann Bildungsstätte, an educational center in Bad Malente-Gremsmühlen

- Many schools across Germany

- The Gustav-Heinemann-Brücke, a bridge over the Spree river in Berlin (since 2005)

See also

In Spanish: Gustav Heinemann para niños

In Spanish: Gustav Heinemann para niños