Haiti indemnity controversy facts for kids

The Haiti indemnity controversy is about a deal made in 1825 between Haiti and France. France demanded that Haiti pay a huge amount of money, 150 million francs, as a "thank you" for recognizing Haiti's independence. This money was meant to pay back former French slave owners and colonists for their "lost property" – including people who had been enslaved – after the Haitian Revolution. This debt was a massive burden, taking about $21 billion out of Haiti's economy over time. The amount was later lowered to 90 million francs in 1838. Haiti ended up paying around 112 million francs in total. For 122 years, from 1825 to 1947, this debt seriously slowed down Haiti's growth. A big part of Haiti's money went to paying interest and parts of the debt, leaving little for things like roads, schools, and hospitals.

France sent several warships to Haiti in 1825 to demand these payments. This was 21 years after Haiti declared its independence in 1804. Because France's demands were so high, Haiti had to borrow large sums from French banks, which made these banks and their owners very rich. Even after France received its last direct payment in 1888, the United States government got involved. In 1911, the U.S. took control of Haiti's money to make sure interest payments related to the debt continued. By 1922, Haiti's remaining debt to France was shifted to American investors. It took until 1947 – about 122 years – for Haiti to finally pay off all the related interest to the National City Bank of New York (now Citibank). In 2016, the French Parliament officially cancelled the 1825 order from Charles X, but France has not offered any reparations (money to make up for past wrongs). Many people say these debts are a main reason for Haiti's poverty today. In 2022, The New York Times published a detailed investigation into this topic.

Contents

History of Haiti's Independence Debt

The Rich Colony of Saint-Domingue

Before 1800, Saint-Domingue (which is now Haiti) was the richest and most productive European colony in the world. France became very wealthy by using enslaved people to work on its plantations. About one-third of all enslaved people brought across the Atlantic Ocean ended up in Saint-Domingue. Between 1697 and 1804, French colonists brought 800,000 enslaved people from West Africa to work on huge farms.

By 1790, Saint-Domingue had 520,000 people, and 425,000 of them were enslaved. Many enslaved people died because the French often worked them to death. It was cheaper for the French to bring in more enslaved people than to provide for their needs. At that time, goods from Haiti made up 30% of all French trade. Haiti's sugar was 40% of the Atlantic market, and 60% of the coffee in Europe came from the colony.

Haiti Becomes Independent

Haiti's long history of debt started soon after a huge revolt by enslaved people. Haitians fought for and won their independence from France in 1804. The U.S. President Thomas Jefferson was worried that enslaved people gaining freedom in Haiti might inspire similar revolts in the United States. So, he stopped the aid that the previous president, John Adams, had started and tried to keep Haiti isolated from other countries.

Haiti hoped that the United Kingdom would support its independence because of Britain's difficult history with France. Haiti even offered British merchants lower taxes on goods. However, at a meeting in 1815, the British government agreed not to stop France from trying to take back Saint-Domingue. In 1823, the United Kingdom recognized the independence of other countries in the Americas, like Colombia and Mexico, but not Haiti. This was very disappointing for Haitians.

Until France recognized Haiti's independence, Haitians feared that France would try to conquer them again. Haiti also spent a lot of money buying weapons to defend itself. President Jean-Pierre Boyer knew that Haiti needed international recognition to improve. He sent people to talk with France. In 1823, Haiti offered to remove all taxes on French products for five years, but France refused. By 1824, President Boyer started preparing Haiti for war. He moved weapons inland for better protection. Haitian representatives went to Paris and offered to pay France some money, but France still refused to fully recognize Haiti's independence.

Charles X's Demand

To show its power, France sent a fleet of warships to Haiti in July 1825. Fourteen French warships with 528 cannons arrived at Port-au-Prince. They demanded that Haiti pay France for the loss of its enslaved people and property.

Charles X, the King of France, then issued an official order. This order said that Haiti's ports would be open to all nations, but French ships would pay half the taxes. Most importantly, it stated:

- "The present inhabitants of the French part of Saint-Domingue shall pay... the sum of one hundred and fifty millions of francs, in order to compensate the former colonists who may claim an indemnity."

- "Under these conditions we grant... to the present inhabitants of the French part of Saint-Domingue the full independence of their Government."

Haitians wanted France to recognize the Spanish part of the island as part of Haiti, but France ignored this. France had given the Spanish part of the island back to Spain in 1814.

So, under Charles X's order, France demanded 150 million francs for Haiti's independence. The King also ordered Haiti to give a 50% discount on taxes for French goods, which made it even harder for Haiti to pay. On July 11, 1825, Haiti's government agreed to pay France.

How the Indemnity Was Paid

France designed the payments to create a "double debt." France would get annual payments, and Haiti would pay French banks interest on the loans needed to make those payments. France saw Haiti's debt as its "main interest in Haiti." Much of the money went directly to France's state-owned bank.

France ordered Haiti to pay the 150 million francs over five years. The first payment of 30 million francs was six times more than Haiti's total yearly income! This forced Haiti to take a loan from a French bank to make the payment. The first 30 million francs required a 24 million franc loan, which completely emptied Haiti's treasury. A French ship then took the money to Paris.

Haiti kept taking loans from France and the United States to make payments. These huge payments were impossible for Haiti, and it often missed payments, causing problems with France. In 1838, France finally agreed to reduce the debt to 90 million francs, to be paid over 30 years. This amount was equal to about $21 billion in 2004. President Boyer, who agreed to these payments, was forced out of Haiti in 1843 by citizens who wanted lower taxes and more rights.

By the late 1800s, 80% of Haiti's money was used to pay foreign debt. France received the most, followed by Germany and the United States. A French bank, Crédit Industriel et Commercial (CIC), saw how much money state banks made from other French colonies. Haiti took out two large loans from CIC in 1874 and 1875, greatly increasing its debt. French banks charged Haiti 40% of the loan just for fees. CIC ended up controlling "much of Haiti's financial future." Some historians describe these loans as an early example of "neocolonialism through debt," meaning controlling a country through its money.

From 1880 to 1881, Haiti allowed the creation of the National Bank of Haiti (BNH), which was based in Paris and controlled by CIC. One of the bank's board members was related to a French slave trader who had made money when France controlled Haiti. CIC took $136 million (in 2022 U.S. dollars) from Haiti and gave it to its shareholders, who made 15% profit each year. None of this money went back to Haiti. These funds cost Haiti at least $1.7 billion in development. Under the French-controlled BNH, France oversaw Haiti's money, and every transaction had a fee. CIC's profits were often larger than Haiti's entire budget for public works. The French government finally recognized the payment of 90 million francs in 1888. Over about 70 years, Haiti paid 112 million francs to France, which is about $560 million in 2022 money.

United States Takes Control

In 1903, Haitian officials accused the BNH of fraud. By 1908, Haiti's Minister of Finance wanted the BNH to work for Haitians. However, French officials started planning how to keep their financial control. Businesses from the United States had also been trying to gain control in Haiti for years. From 1910 to 1911, the United States Department of State supported American investors, led by the National City Bank of New York, to take control of the National Bank of Haiti. They created a new bank, the Bank of the Republic of Haiti (BNRH). This new bank often held back payments from the Haitian government, which led to unrest.

France still had a share in the new bank. After the Haitian president was overthrown in 1914, the National City Bank and BNRH demanded that U.S. Marines take Haiti's gold reserve, which was about $500,000. This gold was put into the National City Bank's vault in New York City. When Haiti's president was overthrown again in 1915, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson ordered an invasion of Haiti to protect American business interests.

Six weeks later, the United States took control of Haiti's customs houses, government offices, banks, and national treasury. For the next 19 years, until 1934, the United States used 40% of Haiti's national income to repay debts to American and French banks. In 1922, the National City Bank fully bought BNRH, moved its headquarters to New York City, and Haiti's debt to France was moved to American investors. Haiti made its final payment related to the indemnity to National City Bank in 1947. At that time, the United Nations reported that Haitians were "often close to the starvation level."

What Happened After

According to The New York Times, these payments cost Haiti a lot of its chances to grow and develop. Experts say it removed about $21 billion to $115 billion from Haiti's growth over two centuries. This amount is like one to eight times Haiti's total economy. The history of Haiti's debt is not taught in schools in France. Many rich French families have also forgotten that their ancestors profited from Haiti's debt payments.

President of France François Hollande later called the money Haiti paid to France "the ransom of independence." In 2016, the French Parliament officially cancelled the 1825 order, which was a symbolic gesture.

Requests for Reparations

Aristide's Government

In 2003, President of Haiti Jean-Bertrand Aristide demanded that France pay Haiti over $21 billion U.S. dollars. He said this was the modern value of the 90 million gold francs Haiti was forced to pay France after gaining its freedom. French and Haitian officials later told The New York Times that Aristide's demands for reparations led to French and Haitian officials working with the United States to remove Aristide from power. France was worried that paying reparations to Haiti would set a precedent for other former colonies, like Algeria.

In February 2004, a coup d'état (a sudden, illegal takeover of government) happened against President Aristide. The United Nations Security Council, where France is a permanent member, first refused to send international peacekeeping forces to Haiti. However, three days later, just hours after Aristide's controversial resignation, the Security Council voted to send troops. The temporary prime minister who took office after the coup later withdrew the demand for reparations, calling it "foolish" and "illegal."

Myrtha Desulme, who leads the Haiti-Jamaica Exchange Committee, said that the call for reparations "could have something to do with it, because they [France] were definitely not happy about it." She believed that Aristide had good reasons for his demand, because "that is what started the downfall of Haiti."

After the 2010 Earthquake

After the terrible 2010 Haiti earthquake, the French government formally asked other countries in January 2010 to completely cancel Haiti's foreign debt. Many people, including journalists from The New York Times, have explained how Haiti's current problems come from its colonial past. They point to the early 19th-century demand for money and how it severely drained Haiti's government and economy.

Images for kids

-

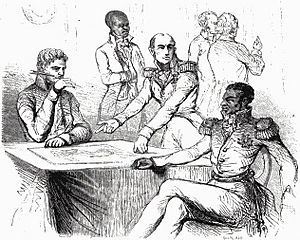

Engraving titledː

"His Majesty, Charles X, The Beloved, recognizing

the Independence of Saint-Domingue

See also

In Spanish: Deuda de Independencia de Haití para niños

In Spanish: Deuda de Independencia de Haití para niños

- Chilean independence debt

- External debt of Haiti

- France–Haiti relations

- Foreign relations of Haiti

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |