Hark, Hark! The Dogs Do Bark facts for kids

"Hark, Hark! The Dogs Do Bark" is a well-known English nursery rhyme. No one is completely sure when it started. Experts think it could be from as early as the late 1000s or as late as the early 1700s. The rhyme first appeared in print in the late 1700s. However, a similar rhyme was written down about a hundred years before that.

Some historians believe the rhyme's words were inspired by real events in English history. Others think it just talks about a common worry about strangers. Those who link it to history often point to the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s. This was when King Henry VIII closed down many religious houses. They also suggest the Glorious Revolution of 1688 or the Jacobite rising of 1715. The word jag in the rhyme, which meant a fancy clothing style in the 1500s, also makes some people think it's from that time.

The rhyme is still popular today, mostly with children. It's so famous that writers sometimes use it in their work, even for adults. They might change the words a bit for fun. Famous writers like James Thurber and D.H. Lawrence have used it. L. Frank Baum, who wrote The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, even wrote a story based on the rhyme.

The rhyme is listed in the Roud Folk Song Index as number 19,689. This index keeps track of folk songs and rhymes.

Contents

Rhyme Words

In the early 1800s, the rhyme was usually printed like this:

Hark, hark! the dogs do bark,

Beggars are coming to town.

Some in rags, some in jags,

And some in velvet gowns.

You might find small changes in how the rhyme is written. For example, rags and jags are sometimes swapped around. Some versions even use tags instead of jags. A few versions say only one person wears a velvet gown. One old version says the gown is silken instead of velvet.

In the 1800s, there was no single way to order rags and jags. While tags was less common, it did appear in some early books. In Britain, it was seen in 1832. In America, it was used even earlier, in 1824.

Some books add a second verse to the rhyme. It starts with "Some gave them white bread / Some gave them brown." But these lines usually belong to another rhyme called "The Lion and the Unicorn."

First Printed Copies

The rhyme seems to have been first printed in 1788. It was in a book called Tommy Thumb's Song Book. The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library says it was in this book under the title "Hark Hark". We don't know if it was in earlier versions of that songbook, which first came out in 1744.

The rhyme was printed again before 1800. It appeared in the first edition of Gammer Gurton's Garland in 1794. We know this because it's in the 1810 edition, and that book says parts of it were printed earlier.

Where the Rhyme Came From

No one is completely sure how "Hark Hark" started. Different historians have different ideas.

One idea is that the rhyme is about the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s. When monasteries closed, many people lost their homes and jobs. They had to wander around towns looking for help, like beggars.

Another idea links the rhyme to the Glorious Revolution of 1688. This was when William of Orange from the Netherlands became King of England. Some think the word "beggar" might have been a play on the name "Beghard", which was a group of poor religious people in Europe.

Some historians also suggest the rhyme comes from the Tudor period (the 1500s). They don't always say why, but it fits with the idea of many people needing help during that time.

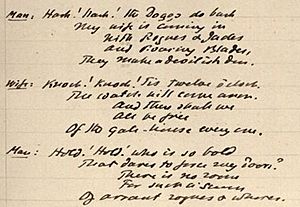

It's tricky to figure out the rhyme's exact start date because there's another old song with the same first line. A song from 1672, also called "Hark, Hark, the Dogs Do Bark," is not a nursery rhyme. It's about a wife and her noisy friends, not beggars. Its first verse goes:

Hark, hark! the dogs do bark,

My wife is coming in,

With rogues and jades and roaring blades,

They make a devilish din.

Sabine Baring-Gould, a historian, noticed this older song. He thought the nursery rhyme came later, after 1714. He also pointed out that the first line is similar to one used by Shakespeare in his play The Tempest, written around 1610.

Right: A portrait of Henry VIII from the 1530s, showing many small jags cut into his clothes. These cuts let the shirt underneath puff through.

The meaning of the word jags might also help date the rhyme. In the mid-1800s, rags and jags meant torn pieces of clothing. But in earlier centuries, jags meant a fashion style. It was about cutting slits or patterns into clothes, especially to show the fabric underneath. This style was popular in the Tudor era (1500s). For example, William Harrison wrote in 1577 about clothes "full of jags and cuts." Shakespeare also used the word in The Taming of the Shrew in 1594.

Even historians who think the rhyme is from the Tudor period don't always agree on why. Some just state it's from then. Others link it to traveling actors who were seen as "beggars." Linda Alchin's book, The Secret History of Nursery Rhymes, explains what jags meant in Tudor fashion. But she doesn't say that the word itself proves the rhyme is from that time.

Chris Roberts, in his 2004 book about nursery rhymes, talks about these different ideas. But he also believes the rhyme has a "universal theme." This means it could describe any time from the Middle Ages until now. It's just about strangers coming to town.

In the 1830s, John Bellenden Ker had a very unusual theory. He thought many English rhymes, even silly ones, actually had hidden meanings from after the Norman conquest in 1066. He believed they were originally in Old English and their meanings were forgotten. Ker thought you could find the original meanings by looking for similar-sounding words in 16th-century Dutch.

Ker wrote several books about this. He thought "bark" in the rhyme came from a Dutch phrase meaning "harasser of the bee," where "bee" meant the English people. He thought "town" came from a Dutch word for "rope," meaning a hangman's noose. With these ideas, Ker concluded that "Hark Hark" was a protest against the Norman government and the Catholic Church. Most people didn't agree with Ker's theory. Critics called it a "delusion" and a "literary mania."

How the Rhyme is Used Today

The rhyme became so well-known in England and the United States that writers often mentioned it. They might quote the whole rhyme or just its first line.

Sometimes, writers would change a few words to make a point. For example, in 1832, someone wrote about new politicians coming to London. They changed "some in velvet gown" to "none in velvet gown" to show how different the new politicians were. In 1888, a cartoon about taxes changed the clothing names to "Italian rags," "German tags," and "English gowns."

Even without changes, the rhyme has been used to explain or highlight something. In 1835, an article used "Hark Hark" to talk about new laws in Britain. Theodore W. Noyes used it in 1900 to describe the people visiting the Sultan of Sulu.

The rhyme has also been used as an epigraph. This means it's a short quote at the beginning of a book or chapter. Poet Adeline Dutton Train Whitney used it in the 1850s to start one of her works. More recently, it's been used at the start of chapters in books by economists and journalists.

In 1953, the first line of the rhyme was even said in the New Zealand House of Representatives. A politician used it to interrupt another, saying, "Hark, hark, the dogs do bark! It is difficult to get a word in."

In the book Men At Arms by Terry Pratchett, "Hark, Hark" is said to be part of the rules for a group called the Beggars Guild.

Other Versions and Stories

Hark, hark, the dogs do bark.

But only one in three.

They bark at those in velvet gowns,

But never bark at me.

The Duke is fond of velvet gowns,

He'll ask you all to tea.

But I'm in rags, and I'm in tags,

He'll never send for me.

Hark, hark, the dogs do bark,

The Duke is fond of kittens.

He likes to take their insides out,

And use their fur for mittens.

When the Communist Party of Italy started in 1921, D.H. Lawrence wrote a poem about it. The poem, "Hibiscus and Salvia Flowers," begins with a changed version of "Hark Hark":

Hark! Hark!

The dogs do bark!

It's the socialists come to town,

None in rags and none in tags,

Swaggering up and down.

James Thurber's 1950 fantasy book The 13 Clocks also uses the rhyme. A prince sings different versions of "Hark Hark" to annoy an evil Duke. Each verse changes the rhyme to criticize the Duke more and more.

The rhyme has also been used as the main idea for longer stories. Mary Senior Clark wrote a two-part story in 1868 based on it. L. Frank Baum, the author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, wrote a story called "How the Beggars Came to Town" in 1897. Both authors used the rhyme at the start of their stories.

In 1872, an anonymous writer used each line of the rhyme as a heading for a much longer poem called "The Beggars." Each part of the poem expanded on the line it quoted. In 1881, Mary Eleanor Wilkins Freeman wrote a 50-verse poem about a "beggar king" and his family, using the traditional lines throughout.

A funny, two-verse version of the rhyme is said in the 1977 movie The Prince and the Pauper. It's not in the original book by Mark Twain, but was added for the film.

Music Recordings

"Hark Hark" has been on many music recordings for children. The first known recording was by Lewis Black in the 1920s. It was part of an "album" of eight records called Songs for Little People. "Hark Hark" was in a mix of songs on the third record.

Other famous artists have recorded it too:

- Derek McCulloch, known as Uncle Mac, on Nursery Rhymes (No. 4).

- Mike Sammes and The Michael Sammes Singers on Nursery Rhyme Toys (1959).

- Wally Whyton on A Treasury of 250 Favourite Children's Songs (1976).

- An unknown artist, but linked to Rupert Bear, on Rupert Sings a Golden Hour of Nursery Rhymes (1972).

A rock version, not for kids, was recorded by Terry Edwards and the Scapegoats in 2008. It was on a single record as the B-side to "Three Blind Mice." Most of this recording doesn't have singing, but the rhyme appears in the middle.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |