Harry Harlow facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Harry F. Harlow

|

|

|---|---|

| Born |

Harry Frederic Israel

October 31, 1905 |

| Died | December 6, 1981 (aged 76) Tucson, Arizona, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Reed College, Stanford University |

| Spouse(s) | Clara Mears (1932-1946) Margaret Kuenne (1946-1971) Clara Mears (1972-1981) |

| Awards | National Medal of Science (1967) Gold Medal from American Psychological Foundation (1973) Howard Crosby Warren Medal (1956) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychology |

| Doctoral advisor | Lewis Terman |

| Doctoral students | Abraham Maslow, Stephen Suomi |

Harry Frederick Harlow (born October 31, 1905 – died December 6, 1981) was an American scientist who studied the mind, known as a psychologist. He did most of his important research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. In 2002, a study showed that Harlow was the 26th most often mentioned psychologist of the 20th century.

Contents

Understanding Harry Harlow's Life Journey

Harry Harlow was born on October 31, 1905. His parents were Mabel Rock and Alonzo Harlow Israel. He grew up in Fairfield, Iowa, as the third of four brothers. Not much is known about his early life. In a book he started writing, he mentioned that his mother was not very warm towards him. He also struggled with sadness throughout his life.

After studying for a year at Reed College in Portland, Oregon, Harlow was accepted into Stanford University. He got in through a special test that showed his natural ability. At first, he studied English, but his grades were not good. So, he decided to change his major to psychology.

Studying at Stanford University

Harlow went to Stanford in 1924. He later became a graduate student in psychology. He worked closely with Calvin Perry Stone, who studied animal behavior, and Walter Richard Miles, an expert in vision. All of them were guided by Lewis Terman. Terman was famous for creating the Stanford-Binet IQ Test. He greatly influenced Harlow's future career.

After earning his PhD in 1930, Harlow changed his last name from Israel to Harlow. Terman suggested this change. He was worried that a name like Israel might cause problems, even though Harlow's family was not Jewish.

Building a Research Lab

Right after finishing his PhD, Harlow became a professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He tried to get the Psychology Department to give him a good lab space, but he was not successful. So, Harlow found an empty building near the university. With help from his students, he turned it into what became known as the Primate Laboratory. This was one of the first labs of its kind in the world.

Under Harlow's leadership, this lab became a place for new and important research. About 40 students earned their PhDs there.

Awards and Achievements

Harlow received many awards and honors for his work. He was chosen to be part of the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1951. He also received the Howard Crosby Warren Medal in 1956. In 1957, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society. He received the National Medal of Science in 1967. He was also elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1961. In 1973, he received the Gold Medal from the American Psychological Foundation.

He also held important leadership roles. He led the Human Resources Research branch of the Department of the Army from 1950 to 1952. From 1952 to 1955, he led the Division of Anthropology and Psychology of the National Research Council. He was also a consultant to the Army Scientific Advisory Panel. From 1958 to 1959, he served as president of the American Psychological Association.

Family Life and Later Years

Harlow married his first wife, Clara Mears, in 1932. Clara was one of the special students Terman studied at Stanford because she had a very high IQ. She was Harlow's student before they started a relationship. They had two sons, Robert and Richard. Harlow and Mears divorced in 1946.

In the same year, Harlow married Margaret Kuenne, who was also a child psychologist. They had two children together, Pamela and Jonathan. Margaret became sick with cancer in 1967 and passed away on August 11, 1971. Her death caused Harlow to feel very sad again. He received treatment to help him cope. In March 1972, Harlow married Clara Mears again. They lived together in Tucson, Arizona, until Harlow passed away in 1981.

Harlow's Famous Monkey Studies

Harlow arrived at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1930. He had just finished his doctorate under the guidance of researchers like Calvin Stone and Lewis Terman. He started his career by studying non-human primates, which are monkeys and apes. He worked with primates at the Henry Vilas Zoo. There, he created the Wisconsin General Testing Apparatus (WGTA). This tool helped him study how monkeys learn, think (cognition), and remember.

Through these studies, Harlow noticed something interesting. The monkeys were developing ways to solve his tests. He called this "learning to learn," which later became known as learning sets.

Studying Infant Monkeys

To study how these learning sets developed, Harlow needed to observe young primates. So, in 1932, he started a group of rhesus macaques that would have babies. Because of his research, Harlow needed to have baby monkeys available regularly. He chose to raise them in a nursery instead of with their mothers. This way of raising them, called maternal deprivation, is still a very debated topic today. It is sometimes used to study how early difficult experiences affect primates.

Harlow and his team learned how to take care of the baby monkeys' physical needs. However, the monkeys raised in the nursery were very different from those raised by their mothers. These nursery-raised infants seemed a bit strange. They were shy, had trouble interacting with others, and often clung to their soft cloth diapers. On the other hand, babies who grew up only with their mothers but no other young monkeys sometimes showed fear or aggression.

The Importance of "Contact Comfort"

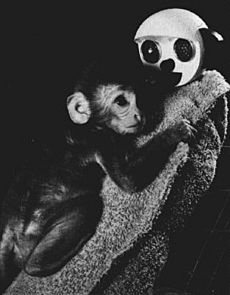

Harlow noticed how much the baby monkeys liked the soft cloth of their diapers. He also saw how not having a mother figure affected them. This led him to study the special bond between a mother and her baby. At the time, in the early 1900s, scientists like B. F. Skinner and others who believed in behaviorism were debating with John Bowlby. They discussed how important a mother is for a child's growth, what their relationship is like, and how physical touch affects them.

To explore this debate, Harlow made fake mothers for the baby rhesus monkeys. He made them from wire and wood. Eventually, Harlow realized that the mother-baby relationship was about more than just milk. He found that "contact comfort," which is the feeling of closeness and touch, was very important for the healthy development of infant monkeys and children. This research strongly supported Bowlby's ideas about how important love and interaction between a mother and child are.

Later experiments showed that the baby monkeys used the fake mothers as a safe place to explore from. They also used them for comfort and protection when they were in new or scary situations. Another important finding, which is still widely accepted, was that not having enough contact comfort caused stress for the monkeys. The digestive problems they had were a physical sign of this stress.

These findings were very important because they went against common advice at the time. Many people believed that too much physical contact would spoil children. Also, the main idea in psychology, behaviorism, thought that emotions were not very important. Feeding was believed to be the most important part of forming a bond between a mother and child. However, Harlow concluded that nursing made the mother-child bond stronger because of the close body contact it provided. He described his experiments as a study of love. He also believed that both a mother or a father could provide contact comfort. While this idea is widely accepted now, it was a new and revolutionary thought at the time.

Studying Social Isolation

Some of Harlow's last experiments looked at what happens when monkeys are kept away from others. He wanted to create an animal model to study sadness. This study is the most debated part of his work. It involved keeping baby and young monkeys alone for different amounts of time.

Monkeys that were kept alone had trouble interacting with others when they were put back into a group. They seemed unsure how to act around other monkeys of their kind (conspecifics). They mostly stayed away from the group. This showed how important social interaction and experiences are for young monkeys to learn how to interact with others. This also applies to children.

Some people who criticized Harlow's research pointed out that for young rhesus monkeys, clinging is necessary for survival. But for humans, it's not the same. They suggested that when his findings were applied to humans, they might overstate the importance of contact comfort and understate the importance of nursing.

Harlow first shared the results of these experiments in a speech called "The Nature of Love." He gave this speech at the 66th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association in Washington, D.C., on August 31, 1958.

Effects of Isolation on Monkeys

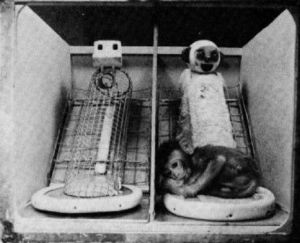

Starting in 1959, Harlow and his students began to share what they observed about the effects of being partially or completely alone. Partial isolation meant raising monkeys in bare wire cages. They could see, smell, and hear other monkeys, but they could not touch them. Total social isolation meant raising monkeys in special rooms where they had no contact at all with other monkeys.

Harlow and his team reported that partial isolation caused problems like blank staring and monkeys repeatedly circling in their cages. Some monkeys in the study were kept alone for 15 years.

In the total isolation experiments, baby monkeys were left alone for three, six, 12, or 24 months. These experiments resulted in monkeys that were very troubled psychologically.

Harlow tried to help the monkeys who had been isolated for six months. He put them with monkeys who had been raised normally. These attempts to help them recover had limited success. Harlow wrote that being completely alone for the first six months of life caused "severe problems in almost every part of social behavior." Monkeys who were isolated and then put with normal monkeys their age "only partly recovered simple social behaviors." Some monkey mothers who were raised in isolation showed "acceptable mothering behavior when forced to accept contact with an infant for several months, but did not recover further." Monkeys isolated and then given to fake mothers developed "basic ways of interacting with each other."

However, when six-month isolated monkeys were put with younger, three-month-old monkeys, they "almost completely recovered socially for all situations tested." Other researchers confirmed these findings. They found no difference between monkeys helped by younger peers and those raised by their mothers. But they found that fake mothers had very little effect on recovery.

Since Harlow's important work on touch, newer research has found more evidence. This evidence supports that touch during infancy is very important for health. It also shows that not having enough touch can be harmful.

Timeline of Harry Harlow's Life

| Year | Event |

| 1905 | Born October 31 in Fairfield, Iowa. |

| 1930–44 | Worked at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Married Clara Mears. |

| 1939–40 | Was a Carnegie Fellow of Anthropology at Columbia University. |

| 1944–74 | Became the George Cary Comstock Research Professor of Psychology. |

| 1946 | Divorced Clara Mears. |

| 1948 | Married Margaret Kuenne. |

| 1947–48 | Served as President of the Midwestern Psychological Association. |

| 1950–51 | Served as President of the Division of Experimental Psychology, American Psychological Association. |

| 1950–52 | Led the Human Resources Research Branch, Department of the Army. |

| 1953–55 | Led the Division of Anthropology and Psychology, National Research Council. |

| 1956 | Received the Howard Crosby Warren Medal for his contributions to experimental psychology. |

| 1956–74 | Directed the Primate Lab at the University of Wisconsin. |

| 1958–59 | Served as President of the American Psychological Association. |

| 1959–65 | Was a Sigma Xi National Lecturer. |

| 1960 | Received the Distinguished Psychologist Award from the American Psychological Association. Was a Messenger Lecturer at Cornell University. |

| 1961–71 | Directed the Regional Primate Research Center. |

| 1964–65 | Served as President of the Division of Comparative & Physiological Psychology, American Psychological Association. |

| 1967 | Received the National Medal of Science. |

| 1970 | His wife, Margaret, passed away. |

| 1971 | Was a Harris Lecturer at Northwestern University. Remarried Clara Mears. |

| 1974 | Became an Honorary Research Professor of Psychology at the University of Arizona (Tucson). |

| 1975 | Received the Von Gieson Award from the New York State Psychiatric Institute. |

| 1976 | Received the International Award from the Kittay Scientific Foundation. |

| 1981 | Passed away on December 6. |

See also

In Spanish: Harry Harlow para niños

In Spanish: Harry Harlow para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |