Havasupai facts for kids

| Havsuwʼ Baaja | |

|---|---|

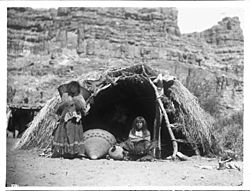

A Havasupai woman in ceremonial attire

|

|

| Total population | |

| About 730 (2017) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Supai, Arizona | |

| Languages | |

| Havasupai, English | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Yavapai, Hualapai |

The Havasupai people (who call themselves Havsuw' Baaja) are a group of Native Americans. They have lived in the Grand Canyon for at least 800 years. Their name, Havasupai, means "people of the blue-green water." Havasu means "blue-green water" and pai means "people."

They mainly live in an area called Havasu Canyon. Long ago, their land was as big as the state of Delaware. But in 1882, the United States government made the tribe give up almost all their land, leaving them with only 518 acres. A "silver rush" (when many people came looking for silver) and the building of the Santa Fe Railroad damaged their fertile land. When the Grand Canyon became a national park in 1919, the Havasupai faced more challenges because the National Park Service used their land.

For many years, the tribe used the U.S. legal system to get their land back. In 1975, they succeeded! They got back about 185,000 acres of their original land through the Grand Canyon National Park Enlargement Act.

To survive, the Havasupai tribe now relies on tourism. Thousands of people visit their beautiful streams and waterfalls at the Havasupai Indian Reservation each year.

Contents

Havasupai History

Early Connections with the Hualapai

The Havasupai and the Hualapai are ethnically very similar. However, they are now separate groups because of U.S. government policies. The Hualapai people had different groups, and the Havasupai were one of these groups, known as the "Havasooa Pa'a."

Life Before 1882

Traditionally, the Havasupai survived by farming, hunting, and gathering food. Even though the Grand Canyon is mostly rugged, their reservation had green plants and the clear, blue-green water of Havasu Creek. This is why their name means "the People of the Blue-Green Waters."

The Havasupai have lived in the Grand Canyon area for over 800 years. We don't know much about them before 1776, when a Spanish priest named Francisco Garcés met them. Garcés reported seeing about 320 Havasupai people. This number decreased over time due to westward expansion and natural events.

In the early 1800s, the Havasupai were not as affected by U.S. expansion as other Native American groups. Life didn't change much until silver was found in 1870 near Cataract Creek. Many miners came to the area, which the Havasupai did not like. They asked for help to protect their land, but it didn't do much good. In 1880, President Rutherford Hayes created a small protected area for the tribe, but it didn't include the mining areas.

During this time, the Havasupai had mixed relationships with other Native American tribes. They had strong ties with the Hopi tribe, who lived nearby. They traded a lot, and the Hopi introduced crops like gourds and sunflowers, which became important foods for the Havasupai. However, the Havasupai also had enemies, like the Yavapai and Southern Paiute, who would sometimes steal or destroy their crops.

Challenges from 1882 to 1920

In 1882, President Chester A. Arthur ordered that all land on the canyon plateau, which the tribe used for winter homes, would become U.S. public property. This order left the Havasupai with only 518 acres of land in Cataract Canyon. They lost almost all their original territory. Reports say the Havasupai didn't even know about this order for several years.

Losing their land wasn't their only problem. More settlers in the area meant less game for hunting. Also, poor farming methods led to soil erosion and food shortages. Contact with settlers also brought deadly diseases like smallpox, influenza, and measles. By 1906, only 166 tribal members remained. This was half the number Garcés saw in 1776. At one point, there were only 40 women and 40 men old enough to have children, which greatly reduced the tribe's population.

In the 1800s, the railway system grew a lot. In 1897, a train line was built directly to the Grand Canyon, opening in 1901. In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt visited the Grand Canyon and met two Havasupai people. He told them about the park being created and that they would have to leave the area. The Grand Canyon became a national monument in 1908 and a National Park in 1919. The Havasupai were finally forced to leave Indian Garden by the National Park Service in 1928.

Fighting for Land: 1921 to 1975

Health problems among the Havasupai meant that many babies and children died, causing a whole generation to be lost. As years passed, the Havasupai realized they needed to adapt to American society to survive. Some tribal members started working with horses, on farms, or for the Grand Canyon National Park. The Havasupai tried to keep their traditions alive, but the government and Park Service often ignored their efforts. They even tore down traditional homes and replaced them with cabins. It became clear that the Park Service wanted the remaining 518 acres of Havasupai land.

During this time, the tribe kept fighting the government to get their land back. In 1968, they won their case against the United States in the Indian Claim Commission. The court found that parts of their land were taken illegally in 1882. The tribe was supposed to get money for the land, which was about 55 cents an acre, totaling over one million dollars. This case was important because it proved the government had wrongly taken their land, but the land itself was not returned.

However, the Havasupai used this victory to continue their fight in the 1970s. In 1974, with support from the Nixon administration and major newspapers, the tribe pushed for a bill (S. 1296) in Congress that would return their land. After months of debate, the bill finally passed both houses of Congress. President Gerald Ford signed it into law on January 4, 1975. This law gave the Havasupai about 185,000 acres of land to own. Another 95,300 acres were set aside as "Havasupai Use Lands," managed by the National Park Service but available for the Havasupai's traditional use.

Mining also happened in the canyon during this time. Tunnels can still be seen in the campground area, some as deep as 300 feet. The largest mine was in Carbonate Canyon, near Havasu Falls, where old rails and wood can still be found. Lead was mined there for the last time during World War II. Below Mooney Falls, a famous pipe "ladder" went up to a vanadium deposit.

From 1976 to Today

After getting a large part of their land back, the Havasupai tribe began to grow again. While many old daily customs are not practiced as much today, the Havasupai continue to respect and preserve their ancestors' traditions. As of 2019, the tribe has about 730 members, with about 400 living on the reservation.

Today, the tribe uses the beauty of their land to attract tourists to the Grand Canyon. Tribal members often work as guides or helpers for tourists. They also work at the lodge, tourist offices, the café, and other places.

Havasupai Culture and Life

Farming and Agriculture

Before modern times, farming was essential for the Havasupai's survival. In winter, tribe members lived on the canyon plateau. In summer, they returned inside the canyon walls to farm their crops. Even though the Grand Canyon is vast and rugged, it's amazing that the Havasupai could farm and thrive there. Because there wasn't much nutrient-rich soil, it's thought they only farmed about 200 acres on the canyon floor. Even with limited space, their irrigation (watering) technology was very advanced compared to other groups in the Southwest, allowing them to farm intensely.

However, being at the bottom of a canyon made their fields vulnerable to floods from rain and the overflowing of Cataract Creek. For example, in 1911, almost an entire crop field was destroyed. In 1920, the government helped the tribe build a new irrigation system, which mostly stopped soil erosion from floods.

Historically, the main crops for the Havasupai were corn, beans, squash, sunflowers, gourds, and some cotton. Corn was their most important crop and was usually harvested in late summer. While growing corn, they used a farming method called cepukaka. This protected the corn from being blown over by wind. Farmers would loosen the soil around the corn and then pull it into a small hill around the base of the stalk. When the Spanish arrived, the Havasupai also started growing melons, watermelons, and fruit trees. By the 1940s, these new crops became important parts of the Havasupai diet.

Hunting Practices

The bow and arrow were very important for Havasupai hunters. Crafting these tools involved a detailed process of building, bending, and designing. However, with westward expansion, rifles were introduced. Over time, guns became the main hunting tool for men. The Havasupai word for "arrow" even started to mean "bullet" too.

For many years, sheep and deer were the main animals hunted by the Havasupai. They also hunted small animals like rabbits and squirrels for food. Historically, the Havasupai hunted in large groups, and the hunted animals were shared fairly among the hunters. But in the 1900s, due to too much hunting and nearby development, large animals like sheep became scarce. This forced the Havasupai to change their hunting habits, and tribesmen became less likely to share.

Gathering Wild Foods

Havasupai women usually gathered wild plants and seeds. They used two main methods:

- Knocking seeds directly from plants.

- Gathering plant heads before the seeds were ready to fall.

The women preferred to find lighter foods that could be easily moved to the plateau in winter. They also liked dry foods that could be stored for a long time without spoiling. Walnuts, wild candytuft, and barrel cacti were just a few of the many plants and seeds gathered by the women during the spring and summer months.

Modern Havasupai Life

Government

The Havasupai tribe is led by a seven-member tribal council. This council handles most policy matters and is elected every two years. A chairman, chosen from the council members, leads the group. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is in charge of law enforcement and protecting the tribe. The Indian Health Service clinic provides healthcare and emergency services.

Language

The Havasupai language is a dialect of the Upland Yuman language. About 450 people speak it on the Havasupai Indian Reservation in and around the Grand Canyon. It is the only Native American language in the United States spoken by 100% of its native population. The Havasupai language is almost the same as the Hualapai language. However, the two groups are socially and politically separate and use different ways of writing their languages. Speakers of Havasupai and Hualapai consider their languages to be distinct. It is a bit more distantly related to the Yavapai language.

Supai Village

Supai (called Havasuuw by the Havasupai) is the main village of the Havasupai people. It is located at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. Supai is the capital of the Havasupai Indian Reservation. It is home to about 400 tribe members and is one of the most remote towns in the contiguous United States. You can only reach it by taking old U.S. Route 66 and traveling about 60 miles along BIA Road 18 to the trailhead. From the trailhead, it's an 8-mile hike to the village. You can also get there by helicopter or horse. The town has 136 houses, a café, a general store, a tourist office, a lodge, a post office, and a school, among other buildings.

Tourism and the Havasupai

Tourism is the main way the Havasupai tribe earns money. The village gets between 30,000 and 40,000 visitors each year. The tribe charges a fee to enter their land. Visitors must reserve a room at their lodge or a spot at the campground.

Havasupai Trail

The Havasupai Trail starts at Hualapai Hilltop, Arizona. This is at the end of BIA Road 18. There's a big parking lot, a helipad, and portable toilets there. You can travel the trail by walking or riding a horse. Sometimes, helicopter transportation is available. You can also pay for mule service to carry your luggage or packs. The trail to Supai is about eight miles long and goes down about 2,000 feet. The campground is another two miles further, with another drop of about 350 feet.

Havasu Creek

Havasu Creek flows through Supai. The creek has several beautiful waterfalls, including Havasu Falls.

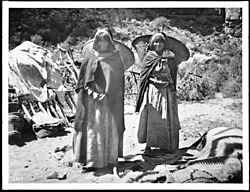

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Havasupai para niños

In Spanish: Havasupai para niños

- Grand Canyon

- Grand Canyon National Park

- Havasu Creek

- In the House of Stone and Light, a 1994 song by Martin Page

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |