Havering Palace facts for kids

Havering Palace was an important royal home in England. It was built before 1066 and used by kings and queens until 1686. The palace was located in the village of Havering-atte-Bower, which is now part of the London Borough of Havering. By 1816, almost nothing was left of the old palace.

Contents

The Palace's Long History

The first records of a royal estate at Havering go back to the time of Edward the Confessor, who was King of England before the Normans arrived. Even though we don't have proof he visited, local stories say he did. The land was owned by Earl Harold in 1066, so it was likely a royal place even then.

After the Norman Conquest, William the Conqueror took over the manor. This royal manor gave the surrounding area a special status called the Royal Liberty of Havering. This meant people living there didn't have to pay certain taxes and had other benefits.

In 1262, King Henry III gave the manor to his wife, Queen Eleanor. After that, it usually belonged to the queen (either the current queen or the queen mother) until Jane Seymour died in 1537. This connection to queens is why the village is called 'Havering-atte-Bower'.

A house was already at Havering by the 1100s, and a lot of building work happened in the 1200s. Many kings and queens stayed there over the years. In 1358, Edward III even held a special court at Havering Palace for five months. This court, called the Marshalsea Court, usually dealt with royal household matters, but here it helped local people with their problems.

Not all visits were peaceful. In 1381, after the Peasants' Revolt, some rebels met the young King Richard II at Havering to ask for forgiveness. But even with their pleas, many were put on trial and executed. Richard also visited in 1397 on his way to see Thomas of Woodstock. This visit led to events that ended with Thomas's murder.

Upkeep and Royal Visits

The palace needed a lot of care. In 1521, about £50 was spent on repairs. A few years later, £230 was used to fix the fence around the park. By the 1530s, the palace and park had five officials to look after different parts of the estate.

The palace was quite spread out and needed constant repairs. Before Elizabeth I visited in 1568, many workers spent days getting it ready. Carpenters, bricklayers, and plumbers worked hard, and even the well was cleaned. Queen Elizabeth I stayed at Havering Palace several times in the 1560s and 1570s. She might have even stayed there before giving her famous speech at Tilbury, though some sources disagree.

Despite earlier repairs, even more work was needed before a visit in 1594. This included fixing rooms, adding new roof beams to the bakehouse, and even getting a new bucket for the well! It seems the palace was always in need of fixing.

In 1596, a survey of the buildings showed that the palace was watertight. It had rooms for important guests and ladies of the court. After Elizabeth, King James I often stayed there, usually for just one night. The palace was given to his wife, Anne of Denmark, as part of her royal income.

A Scottish courtier, George Home, 1st Earl of Dunbar, wrote in 1608 about how healthy hunting at Havering was for the King. He said, "our greatest matters here are hunting and sport for his Majesty's pleasure, the which being his health is the general good of us all."

The Palace's Decline

King Charles I was the last monarch to stay at Havering, from October 29-31, 1638. He was on his way to meet his mother-in-law, Marie de' Medici, at nearby Gidea Hall.

The palace's strong connection to the monarchy might have affected what happened during the Commonwealth period (when England was a republic). Richard Deane, who signed the order for King Charles I's execution, began taking the palace apart. He also had all the grown trees in the park cut down.

After the monarchy was brought back (the Restoration), the house was called Havering House. It was described as "a confused heap of old ruinous decayed buildings." Even though a lot of money was spent on repairs, it became empty sometime between 1686 and 1719 and was reported to be in ruins.

A Latin message in the hall of the current Bower House (which was then called Mount Havering) suggests that parts of that building were made using materials from the old palace. By 1740, so little was left that you couldn't even tell what the old buildings looked like. By 1816, no walls were visible above ground.

The last connections to Havering Palace slowly disappeared. In 1828, the rights to the manor were sold to Hugh McIntosh. His son, David McIntosh, built a new mansion at Havering Park. He also had the current church built in 1878, replacing the old one that had been part of the palace chapel.

What the Palace Was Like

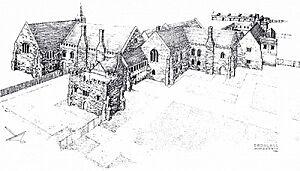

At its biggest, before it started to fall apart, most of the palace was built in the 1200s. A newer part was added in 1576–77. In the late 1500s, it was described as having an irregular shape. You entered through a gatehouse into a group of connected buildings. These included a great chamber (a large main room), royal apartments, two chapels, and rooms for important officials like the Lord Chamberlain.

There were also supporting buildings like kitchens, a buttery (for drinks), a scullery (for washing dishes), a salthouse, a spicery (for spices), and a wet larder (a cool place for food). Beyond these were stables, other outbuildings, and a garden. The parkland around the palace was much larger than the current Havering Country Park. It covered most of the old Havering-atte-Bower area west of the main road.

Who Lived at Havering Palace?

Many kings, queens, and other famous people stayed at Havering Palace at different times:

- Edward the Confessor

- Harold Godwinson

- William I

- Henry II

- John

- Eleanor of Aquitaine

- Joan, Queen of Scotland, who was the sister of King Henry III. She passed away here in 1238.

- Edward III

- Richard II

- Joan of Navarre, Queen of England, who died at the palace in 1437.

- Edward IV

- Henry VIII

- Mary I

- Elizabeth I

- Charles I, who was the last king to stay at Havering.

- Marie de Medici, the Queen of France and mother-in-law to Charles I. She visited but decided to stay at Gidea Hall nearby because the palace was crumbling.

- Richard Cromwell

- Robert Bertie, 3rd Earl of Lindsey

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |