Henriette Renié facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henriette Renié

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Background information | |

| Born | September 18, 1875 Paris, France |

| Died | March 1, 1956 (aged 80) Paris, France |

| Genres | Classical |

| Instruments | Harp |

| Years active | 1886–1955 |

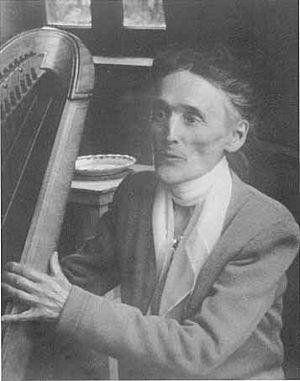

Henriette Renié (born September 18, 1875 – died March 1, 1956) was a famous French harpist and composer. She is known for her many original music pieces and her special way of teaching the harp. This teaching method is still used by harpists today.

Henriette was a very talented musician from a young age. She learned to play the harp quickly and won many important awards. She was also an amazing teacher who helped many students become successful musicians. Henriette became famous at a time when it was unusual for women to be well-known. Her dedication to her beliefs, her family, her students, and her music has inspired many musicians for a long time.

Contents

Becoming a Harp Star

Before she was five years old, Henriette played the piano with her grandmother. She decided she wanted to play the harp after hearing her father perform in Nice. A famous harpist named Alphonse Hasselmans was also playing. Henriette was so inspired that she wanted to learn the harp from him.

She started playing when she was eight. But she was too short to reach the harp's pedals. So, her father invented special extended pedals to help her.

In 1885, Henriette became a student at the Paris Conservatoire. When she was ten, she won second prize in harp performance. The audience wanted her to get first prize. However, the director, Ambroise Thomas, suggested she not receive it. He thought it would make her a professional too soon. This would mean she could no longer take lessons at the Conservatoire.

By age eleven, she won the Premier Prix (First Prize). Her performance at the competition is still seen as one of the best in the Conservatoire's history. At a young age, she played for important people. These included Queen Henriette of Belgium and the Emperor of Brazil. When she was twelve, students from all over Paris wanted her to teach them. Many of these students were much older than her.

After graduating at thirteen, she was allowed to take harmony classes at the Conservatoire. Normally, students under fourteen were not allowed in these classes. In 1891, she won the Prix de Harmonie. In 1896, she won the Prix de Contrepoint Fugue et Composition. Her teachers, Théodore Dubois and Jules Massenet, encouraged her to compose. But she was shy about showing her work. She hid her piece Andante Religioso for six weeks before sharing it. At fifteen, Henriette gave her first solo concert in Paris.

A Life of Music and Challenges

In 1901, Henriette finished her Concerto in C minor. She had started composing it while at the Conservatoire. Her teacher Dubois suggested she show it to Camille Chevillard. He then scheduled it for several concerts. Henriette made great progress for women in music during these concerts. She was the first woman to receive applause for both her performance and her composition.

These concerts showed Henriette as a brilliant performer and a talented composer. They also helped make the harp a respected solo instrument. This inspired other composers like Gabriel Pierné, Claude Debussy, and Maurice Ravel to write music for the harp.

In 1903, she composed a major harp solo called Légende. It was inspired by the poem "Les Elfes" by Leconte de Lisle. That same year, Henriette introduced eleven-year-old Marcel Grandjany to the Conservatoire. However, Hasselmans initially refused him. The next year, Grandjany was accepted as a student. When he was thirteen, Grandjany won the Premier Prix. He later had a very successful career. He brought Henriette's teaching method to the United States at the Juilliard School.

In 1912, Hasselmans and Henriette became friends again. He announced he could no longer teach at the Conservatoire. He wanted her to take his place. However, the Conservatoire was a government school. It needed approval from the Ministry of Education for new teachers. At that time, there was a movement to separate church and state in France. Henriette openly supported the Catholic Church. Because of this, she was not hired. Instead, Marcel Tournier got the position.

Instead, Henriette started her own international competition in 1914, called the "Concours Renié." This competition offered a large money prize. Famous musicians like Ravel and Grandjany were judges over the years.

During World War I, Henriette earned money by giving lessons. She also gave charity concerts almost every night. The money went to a fund that helped artists in need. This was even when battles were happening close to Paris. After the war, a famous conductor, Arturo Toscanini, offered Henriette a contract. She turned it down because her mother was ill. In 1922, she was suggested for the Legion of Honour. But she was rejected because of her religious beliefs.

Henriette started making recordings in 1926 for Columbia and Odeon. Her recordings sold out quickly. Her piece Danses des Lutins won an award. But the recording sessions made Henriette very tired. So, she refused to sign any new contracts. By 1937, Henriette often wrote in her diary about feeling tired. Illness forced her to cancel concerts.

During World War II, Henriette wrote the Harp Method. This became her main focus during the war. It is a detailed guide to harp technique and music. Many important harpists, like Grandjany and Susann McDonald, used it. After the war, students, especially from America, came to Henriette. They then shared her teaching methods with music schools around the world.

Henriette suffered from severe sciatica and neuritis. She also had lung and digestive infections in winter. These illnesses almost made her unable to move. But she continued giving lessons and concerts. When Tournier retired from the Conservatoire, Henriette was offered his job. She politely declined, saying she was older than him. She finally received the Legion of Honor in 1954. The next year, she gave a concert, playing Légende. She said it would be the last time she played it. She died a few months later in March 1956 in Paris, France.

Her Family Life

Henriette's father, Jean-Émile Renié, was the son of an architect. He was good at architecture, but he loved painting. He became an actor and singer, then joined the Paris Opera. Henriette's mother, Gabrielle Mouchet, was related to a famous furniture maker. Her father did not want her to marry Jean-Émile. But he eventually agreed if Jean-Émile continued painting.

The couple had four sons before Henriette was born in Paris. Her older brothers were sometimes rough with her. But she was very close to her fourth brother, François. She would become sad when they were apart. Once, Henriette's nose was broken while playing with her brothers. This is why her nose was not perfectly straight.

Henriette stayed close to her parents. She also liked her nephews and nieces. But she kept some distance from them because her sisters-in-law were jealous. When Henriette's father died, she lost a lot of weight. She then started supporting her mother financially. She also remained close to her brother François, who was isolated because he was deaf and had poor vision.

Beyond the Music

When Henriette was a teenager, her family spent summers in Étretat, Normandy. This was a rare chance for her to meet people her age. She liked one of her brother's friends. But she decided she could not give up her art and career to be with him. She also turned down a marriage proposal from Henri Rabaud three years later. Henriette also paid for her brothers' horse riding lessons. They were not earning much money in the military.

She also paid for a new harp for herself. Even though she was struggling financially, she refused to take money for helping her students pick out harps at Erard. Sometimes, she even gave lessons for free. As a teenager, Henriette worked constantly. She only had one friend, Hasselmans's daughter, who was also her student. Later, she became close to the Chevillard family. She especially liked Camille Chevillard's wife, who was a singer and a spiritual inspiration for Henriette.

Before World War I, Henriette became friends with the family of one of her students, Marie-Amélie Regnier. After winning an award, Marie-Amélie promised that Henriette would be the godmother of her first child. During the war, Henriette helped support the family financially. After the war, Marie-Amélie got married. She then introduced Henriette to her goddaughter. Marie-Amélie's husband was often away for work. So, the child spent more time with her grandmother and godmother than her parents. In 1923, Henriette helped Louise Regnier (Marie-Amélie's mother) buy part of a house. Henriette and her brother François moved in with the Regniers after her mother died. In 1934, Louise Regnier died. She left her granddaughter, Françoise, in Henriette's care. Henriette was very devoted to Françoise.

Henriette was a very religious person. When the French Third Republic government tried to separate the church and state, she openly wore a gold cross. This showed her support for the church. Because of this, the government kept a file on her. She was generally strong in her beliefs. She even tore down German propaganda posters during the war, despite her friends' fears.

Her Lasting Impact

Henriette Renié was very important in promoting the double-action harp made by Sébastien Érard. She also inspired the creation of the chromatic harp. This happened after she complained about harp pedals to Gustave Lyon, who worked for a musical instrument maker.

Salvi, a company that followed Érard, created a "Renié" model harp. The French Institute also created a "Henriette Renié Prize for Music Composition for the Harp." Her book, Méthode complète de harpe, is still widely used by harp students today. She published many works with major French publishers. These pieces are now important parts of the harp music collection. Some other works might still exist as manuscripts but have been lost.

As of 2018, you can find archives about Henriette Renié at the International Harp Archives. These are located in the Special Collections of the Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University. These archives include her personal letters, concert programs, diaries, and other personal items.

Famous Students

- Marcel Grandjany

- Mildred Dilling

- Susann McDonald

- Odette Le Dentu

Her Compositions and Arrangements

\header { tagline = ##f } upper = \relative c' { \clef treble \key ges \major \time 3/8 \tempo 8 = 152 %\autoBeamOff \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"orchestral harp" \partial 8 s16 \times 4/11 { \autoBeamOn << { ees64( ges a! ces d! ees ges ges a ces d!) } \\ { s64*4 d,!64[ ees ges ges] } >> } ees'8-.\p des!16( ces bes aes! bes aes ges aes bes ges) ces8-. bes16( aes ges f ges f ees f ges ees) bes16( c! d!8) ees16( f ges aes bes c! d! ees f ges f bes, bes'8~->) bes8 } lower = \relative c { \clef bass \key ges \major \time 3/8 \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"orchestral harp" s8 ees8-. < ges' bes, >8-. r8 \clef treble ees8 < bes' f >8 < d! bes > ees,8 < bes' f >8 < ees ces > ees, < c'! ges > r8 ees,8( < bes' ges >8) des,( < bes' ges >) ces,( < bes' ges >) c,!( < ees' a,! f >8) bes,( < d'! f, >) } \score { \new PianoStaff << \set PianoStaff.instrumentName = #"Harpe" \new Staff = "upper" \upper \new Staff = "lower" \lower >> \layout { \context { \Score \remove "Metronome_mark_engraver" } } \midi { } }

</score>- Andante religioso, for harp and violin or cello

- Contemplation (1898)

- Concerto in C for harp (1900)

- Légende inspired by Les elfes by Leconte de Lisle (1901)

- Pièce symphonique in three parts, for harp (1907)

- Ballade fantastique based on "Le cœur révélateur" by Edgar Poe, for solo harp, 1907

- Scherzo-fantaisie for harp (or piano) and violin (1910)

- Six pièces pour harpe, 1910

- Danse des Lutins, for harp (1911)

- 2e ballade (1912)

- Six pièces brèves, for harp (1919)

- Deux pièces symphoniques, for harp and orchestra (I. Élégie, II. Danse caprice) (1920)

- Trio for harp, violin, and cello

Arrangements

- Jacques Bosh, Passacaille : sérénade for guitar (1885)

- Théodore Dubois, Ronde des archers (1890)

- Chabrier, Habanera (1895)

- Auguste Durand, Première valse, Op. 83 (1908)

- Bach, Dix pièces (1914)

- Bach, Dix préludes : from the well-tempered clavier (1920)

- Debussy, En bateau, from the Petite suite

- Théodore Dubois, Sorrente

See also

In Spanish: Henriette Renié para niños

In Spanish: Henriette Renié para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |