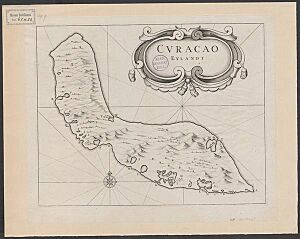

History of Curaçao facts for kids

The history of Curaçao began with the Arawaks, an Amerindian people from South America. They lived on the island for many hundreds of years before Europeans arrived.

Contents

Early History

The first signs of people living on Curaçao are found in Rooi Rincon. People used natural rock shelters there. Scientists found old shells, animal bones, and stone tools. There are also rock paintings. These oldest remains are from about 2900 to 2300 BCE. Similar findings and graves were found at Sint Michielsberg, from about 2000 to 1600 BCE.

Later, pottery from the ceramic period was found at places like Knip and San Juan. These items date from about 450 to 1500 CE. They belong to the Dabajuroid culture, specifically the Caquetio people. The Caquetio came from nearby northwestern Venezuela. Their language shows they were part of the Arawaks group.

The Caquetío lived in small villages with up to 40 people. These villages were often near bays, mostly on the south coast. They grew cassava, fished, collected shellfish, and hunted small animals. They also traded with other native people from nearby islands and the mainland. Homes have been found at Knip and Santa Barbara.

Scientists began studying Curaçao's first inhabitants in the 1800s. An amateur, A.J. van Koolwijk, explored the island and recorded its petroglyphs (rock carvings). Many others have studied Curaçao's early people since then.

European Arrival

Spanish Rule

Alonso de Ojeda from Spain was the first European to visit Curaçao on July 26, 1499. About 2,000 Caquetio people lived there at that time. By 1515, most Caquetios were forced to leave their homes and taken to Hispaniola. The Spanish settled on the island in 1527. They governed it from a city in Spanish-Venezuela.

The Spanish brought many new animals and plants to Curaçao. Horses, sheep, goats, pigs, and cattle came from Europe or other Spanish colonies. They also planted different trees and plants. The Spanish learned some farming methods from the Caquetio people.

Raising animals like sheep, goats, and cattle worked well. The Spanish let cattle roam freely in the fields. Caquetio and Spanish herders took care of them. But farming was not very successful. Also, the salt pans did not produce much salt, and no valuable metals were found. Because of this, the Spanish called the island an isla inutil, meaning a useless island.

Over time, fewer Spaniards lived on Curaçao. However, the number of native residents became stable. It is believed the Caquetio population even grew. In the last years of Spanish rule, Curaçao was used as a large cattle ranch. A few Spaniards lived near Santa Barbara, Santa Ana, and in villages in the western part of the island. Caquetio people lived all over the island.

Dutch Takeover

The Netherlands became independent from Spain in 1581. The Dutch West India Company (WIC) was formed in 1621. In 1633, the WIC lost its base on Sint Maarten to a Spanish fleet. The WIC then became interested in Curaçao. It had an excellent natural harbor for trade and privateering (piracy allowed by the government). The WIC also wanted salt from Curaçao and nearby islands to preserve fish. Curaçao also had blackwood for natural paint, cattle, and other resources.

A WIC fleet led by Admiral Johann van Walbeeck invaded Curaçao in 1634. The Spanish on the island surrendered in San Juan in August. About 30 Spaniards and many Taíno people were sent to Santa Ana de Coro in Venezuela. However, about 30 Taíno families were allowed to stay on the island.

After the conquest, Van Walbeeck ordered the building of Fort Amsterdam. It was built at the mouth of the Sint Anna Bay. Dutch soldiers and enslaved people from Angola built the fort. It became the WIC's main base. The WIC built other forts to protect its claims. A fort was built near a water source in 1634-35. The main Fort Amsterdam began construction in 1635-36. It was shaped like a five-pointed star.

Life was hard for WIC troops in the first three years. They depended on supplies from Europe, which often arrived late. Food was rationed. Soldiers had to bring water from the source. Many soldiers were unhappy due to poor living conditions and hard work. The town of Willemstad began to grow around Fort Amsterdam.

Dutch Control

Spain tried to take Curaçao back from the Dutch. They gathered information by kidnapping and questioning native people. They also captured WIC workers. Spain even sent spies to Curaçao. In 1637, Spain tried to invade with ships and troops. But a storm forced them to turn back.

The WIC leaders in Amsterdam were unsure about Curaçao's future. The forts and soldiers cost a lot, and profits were low. However, Curaçao continued to develop. After the Dutch lost Dutch Brazil in 1654, Curaçao became even more important. Its good location helped trade with Europe, Venezuela, and other Caribbean islands. They also traded with Dutch colonies in North America, like New Netherland.

Peter Stuyvesant was a governor from 1642 to 1644.

Curaçao's population grew steadily. Many Sephardic Jews arrived from former Dutch Brazil. The WIC also invited new settlers from Europe to farm. Even soldiers who finished their service could stay. The goal was to grow enough food for the island. The WIC also wanted farmers to grow crops for sale, like indigo, cotton, tobacco, and sugar cane. The first large farms, called plantations, were built around 1650. These included places like Hato and Santa Barbara. This led to a large number of enslaved people being brought to the island.

Jewish Community

The Sephardic Jews who came from the Netherlands and then-Dutch Brazil since the 1600s greatly influenced Curaçao's culture and economy. Curaçao has the oldest active Jewish community in the Americas, started in 1651. This community also helped early Jewish groups in New Amsterdam (now New York City) and other places in the 1700s and 1800s. After World War II, more Jews from Eastern Europe, called Ashkenazi Jews, came to the island.

Slave Trade and Free Port

For much of the 1600s and 1700s, the main business on the island was the slave trade. Enslaved people were brought from Africa. They were bought and sold at the docks in Willemstad before being sent to other places. Between 1662 and 1669, about 24,000 enslaved people were shipped by Domingo Grillo and Ambrosio Lomelín, with help from the Dutch West India Company.

The WIC sold enslaved people at very low prices. This made it hard for English, French, and Portuguese traders to compete. Enslaved people were bought by traders and then sent to different places in Central and South America. Only a small number of the Africans who arrived stayed on Curaçao.

The enslaved people who stayed on the island worked on the plantations. This cheap labor made farming much more profitable. With trade at the docks and work in the fields, Curaçao's economy grew. This growth was built on the forced labor of enslaved people.

In 1674, the WIC made Curaçao a free port. This meant goods could be traded there without paying high taxes. This made Curaçao very important in international trade. It became one of the richest islands in the Caribbean in the 1600s. This caused problems with other powerful countries like England and France. In 1713, a French captain named Jacques Cassard attacked Curaçao. He eventually left after being paid. The attack caused much damage to the island. In 1716, a small slave revolt happened, but the rebels were caught. Ten rebels were sentenced to death.

In the 1700s, Curaçao tried to keep its strong trading position. But the Spanish Coast Guard stopped illegal trade from Venezuela. Also, England and France became stronger in the Caribbean. These things made Curaçao less important. The island was also not good for growing large amounts of sugar cane, cotton, or tobacco. Curaçao's farming focused on feeding its own people. Still, some food had to be imported. The slave trade remained the most important way for the Dutch to make money.

Dutch Colony

The WIC went bankrupt in 1791. After this, Curaçao officially became a Dutch colony. The Dutch were able to stop the slave revolt of 1795. This uprising was led by Tula, an enslaved person who is a very important figure in Curaçao's history.

In 1795, William V, Prince of Orange fled the Netherlands. He went to Great Britain before the new Batavian Republic was announced. The governor of Curaçao refused to accept the Batavian Republic. He was replaced in 1796. Later, a local militia, helped by French troops, took control.

The British captured Curaçao in 1800 and held it until 1803. They attacked again in 1804 and held the island from 1807 to 1816. After that, they gave it back to the Dutch as part of the Treaty of Paris.

Curaçao is very close to Venezuela. This led to many connections with Venezuelan culture. For example, buildings in 19th-century Willemstad look similar to those in the Venezuelan city of Coro. In the 1800s, Curaçaoans like Manuel Piar and Luis Brión were important in Venezuela's and Colombia's wars for independence. Political refugees from the mainland, like Simon Bolivar, found safety in Curaçao. Children from rich Venezuelan families also came to the island for school.

To save money, the Dutch West Indies colonies were combined into one colony in 1828. But managing the islands from Suriname did not work well. So, in 1845, there were again two West Indian colonies: Suriname, and Curaçao and Dependencies.

Modern Times

The Napoleonic Wars in Europe and British expansion caused Curaçao to change hands several times in the 1800s. The British invaded the island twice, from 1800 to 1803 and from 1807 to 1816. At the same time, many independence movements happened in the Spanish colonies on the mainland. People like Simón Bolívar found help on Curaçao. Curaçaoans like Manuel Piar and Luis Brión also played important roles. In 1815, after Napoleon's defeat, the Treaty of Paris officially gave the island back to the Dutch.

Following England (1834) and France (1848), the Dutch ended slavery in 1863. This changed the economy to wage labor. The Dutch government paid slave owners for their loss. Some former enslaved people moved to other islands, like Cuba, to work on sugar cane farms. Others had nowhere to go. They continued to work for their former owners under a system where they rented land and gave most of their crops to the owner. This system lasted until the early 1900s.

Until the early 1900s, Curaçao's economy relied on trade, farming, and fishing. This changed in 1914 when large amounts of oil were found in Venezuela. Shell quickly built an oil refinery on the island, called Isla Refinery. It was built near a place where enslaved people were once traded.

In the 1920s and early 1930s, Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe came to Curaçao. Many started as street sellers but slowly became successful. They kept their Jewish identity. In the 1980s and 1990s, their numbers greatly decreased. Many older members passed away. Also, due to political and economic problems, many Ashkenazi Jews left the island in the 1980s. They moved to places like the United States and Israel.

On June 8, 1929, Fort Amsterdam was attacked and captured by Venezuelan rebel Rafael Simón Urbina and 250 others. They stole weapons, ammunition, and money from the island. They also captured the Governor, Leonardus Albertus Fruytier, and took him to Venezuela on a stolen American ship. After this attack, the Dutch government decided to keep marines and ships on the island permanently.

During World War II, Curaçao was very important for supplying fuel to the Allied forces. In 1940, before the Netherlands was invaded by Nazi Germany, the British occupied Curaçao. The French occupied Aruba. The presence of these other powers worried Venezuela because the islands were close to its coast. In 1941, US troops occupied the island. They built military airports in Aruba and Curaçao. Their main goal was to fight against possible attacks from German submarines and bombers.

In 1942, German submarines attacked the island's port several times. This port was a main source of fuel for the Allies. In August 1942, the Germans attacked an oil tanker. The US Navy set up the Fourth Fleet to fight enemy ships in the Caribbean. The US Army also sent planes and people to help protect the oil refineries.

In 1954, Curaçao, along with the other Netherlands Antilles, gained political freedom to govern itself.

Workers' Revolt of 1969

In the 1940s and 1950s, the oil refinery brought wealth and modern ways to the island. But this wealth was not shared equally. Workers became unhappy with the pay practices of Royal Shell. Also, the Afro-Curaçaoan people had limited say in the government. On May 30, 1969, a workers' revolt, known as Trinta di mei (May 30th) in Papiamentu, started at the Shell refinery entrance. As workers marched towards the city, a union leader named Wilson Godett was shot by police. Angry workers then set fire to buildings in Punda and Otrobanda.

After the local government allowed Dutch marines to come and restore order, much work was done to make the government better represent the people. Wilson Godett even held a government position for a while.

In the 1980s, Shell left Curaçao. The island then leased the oil refinery to the Venezuelan state oil company, PDVSA. The refinery often causes serious air pollution on a part of the island. There is growing opposition to this. Some call it "the shame of Shell" on Curaçao.

Autonomous Status

Curaçao gained an autonomous status, similar to Aruba, on October 10, 2010.

Unlike the Netherlands, Curaçao is not part of the European Union. So, Curaçao, like Aruba and Sint Maarten, does not have to follow European laws or use the euro currency. However, because of its special relationship with the Netherlands as an overseas territory, the islands can get European funds. They also qualify for EU agreements like the Erasmus+ program. Also, people living in the Caribbean part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands have Dutch citizenship, which means they also have European citizenship.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Curazao para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Curazao para niños

- Canon of Curaçao

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |