History of Upper Canada College facts for kids

The history of Upper Canada College (UCC) began when it was founded in 1829. This school is located in Toronto, Ontario.

Contents

Founding the School

Upper Canada College was started in 1829 by Sir John Colborne, who was the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada at the time. He wanted it to be a school that prepared students for the new King's College (which later became the University of Toronto). UCC was designed like famous public schools in Britain, especially Eton.

Even though it's now a private school, UCC was first created with public money. It received a large grant of 6,000 acres of land, and later another 60,000 acres. The school officially opened on January 4, 1830, with 57 students. By the end of its first year, 140 students had joined.

Before 1829, the school was called the Royal Grammar School. Its first buildings were in downtown Toronto. Soon after opening, plans were made for new, bigger buildings. In 1831, the school moved to its new location at King and Simcoe Streets.

Some people praised the new school. Reverend Thomas Radcliffe said in 1833 that future generations would be thankful for Sir John Colborne's "magnificent foundation" for education. However, the high costs of the new buildings and staff led to some criticism. William Lyon Mackenzie, a newspaper publisher, complained that the college was "extravagantly endowed" and had "splendid incomes" for its teachers.

In 1837, UCC students even helped the government stop Mackenzie's Upper Canada Rebellion. Interestingly, Mackenzie's own sons later attended UCC in 1852.

Under University Control

On March 4, 1837, UCC officially came under the control of King's College (the university). The King appointed the principal, and the Lieutenant-Governor chose the vice-principal and teachers.

In 1838, UCC looked for a new principal. They asked the Archbishop of Canterbury for a suggestion, and John McCaul was chosen. He started his job on January 29, 1839.

In 1842, the famous writer Charles Dickens visited the college. He said it offered "a sound education" at a "very moderate expense." He also called it a "valuable and useful institution."

By 1887, UCC had 300 students, and its buildings were getting too small. The school almost closed when the provincial government, which was a Liberal government, considered using the college's land and money for the university. A politician suggested that UCC should be "abolished" because its education could be found in other high schools.

In response, a group of former students, called "Old Boys," met to save the college. They got support from many alumni, including Lieutenant Governor John Beverley Robinson. The newspapers covered the story widely. In the end, after much discussion, it was decided that UCC would separate from King's College after 50 years. It would then be run by five trustees chosen by the Minister of Education. The plan also included moving the college outside the city, though this part wasn't immediately put into law.

Moving to a New Home

On July 3, 1891, the bell at the old Russell Square campus rang for the last time. A farewell cricket game was played on August 29. The Upper Canada College Old Boys' Association was also created that day.

UCC then moved to its current location, the Deer Park campus, at 200 Lonsdale Road in Forest Hill. The new doors officially opened on October 14, 1891. 43°41′36″N 79°24′15″W / 43.6933°N 79.4042°W

In 1902, a separate Preparatory School building was constructed at the south end of the campus, creating two distinct schools.

World Wars and UCC

More than 400 UCC graduates died during the First and Second World Wars. The first to die was Lt. C. Gordon Mackenzie on October 24, 1914. By the end of World War I, 176 Old Boys had lost their lives.

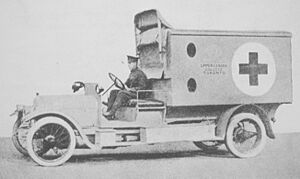

In 1916, the students of UCC bought an ambulance and sent it to France. By May of the next year, it had traveled almost 3,000 miles and carried 5,000 wounded soldiers.

During World War II, UCC welcomed many war refugees. By May 1941, there were 97 refugee students. The school also started a "war chest" to send packages to Old Boys fighting and to help their families.

Historian Jack Granatstein found that over 30% of Canadian generals during World War II were UCC graduates. This included General Harry Crerar, who led the First Canadian Army. In total, 26 Old Boys reached the rank of brigadier or higher in World War II.

In 1920, Prince Edward, who later became King Edward VIII, asked to be UCC's official visitor. The school newspaper, College Times, wrote that the Prince had met many "Old Boys" during World War I and wanted to honor the school. Edward was removed from this role when he gave up the Canadian throne in 1936.

In 1923, The War Book of Upper Canada College was published. It remembered every Old Boy who served in World War I. There are also two gilt boards in the school's main entrance that list the names of those who died in both World Wars.

Vincent Massey's Impact

Vincent Massey, who was the Governor General, became very interested in UCC. He often talked with the principal, Sowby, about the school. They worked together to bring important guests to speak to students or visit the college. Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent helped lay a cornerstone for the school's Memorial Wing. Field Marshal the Viscount Montgomery inspected the cadets and said they were the "best cadet corps" he had ever seen.

During this time, the role of "visitor" was brought back when Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, was appointed to it.

UCC's chapel was built in the early 1950s with money from Vincent Massey. It was dedicated to his wife, Alice Parkin, who was the daughter of a former UCC principal. The chapel even received a piece of the altar cloth used at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

Building Challenges

At the end of the 1950s, UCC faced a big problem. The main building from 1891 was falling apart because it had been poorly built. Cracks appeared, pipes broke, and door frames warped. People worried the tower might collapse. The building was declared unsafe and emptied by March 12, 1958. Classes had to be held in temporary classrooms.

That same year, a big fundraising effort began to build a new main building in the same spot. Ted Rogers, a media leader, donated money to rebuild the famous tower over the main entrance. The Governor General laid the cornerstone in the summer of 1959. Prince Philip visited in the autumn to help with fundraising. The College Times reported that a large crowd cheered when Prince Philip arrived. He toured the new buildings and was given a tie to show he was an honorary "Old Boy."

The new building was officially opened by Vincent Massey and Edward Peacock on September 28, 1960. The cost of the building, $3,200,000, was fully covered by donations.

Late 20th Century Changes

Prince Philip returned in 1969 to give out The Duke of Edinburgh's Award Gold Awards to UCC students.

In 1971, UCC welcomed its first woman to the board of governors, Pauline Mills McGibbon. She later resigned in 1974 when she became the Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario. Five years later, in 1979, UCC celebrated its 150th anniversary. Prince Philip, the college's Official Visitor, attended the celebration. Sandi Ryder became the first woman elected to the college's board of governors that year.

1979 was UCC's 150th birthday, marked by a two-day visit from Prince Philip. He toured the campus and attended a huge dinner at Exhibition Place with over 3,000 people. It was the largest formal dinner ever held in Toronto at the time. Philip praised the special education UCC offered. The next morning, he gave prizes to winners of the first annual Association Run.

By 1980, boarding for younger students ended. Some dorms were turned into computer labs where students learned about new technology.

In 1991, UCC was visited by Árpád Göncz, the Hungarian President, who later enrolled his grandson at the school. In 1993, Prince Philip visited again to officially open new buildings like the Foster Hewitt Athletic Centre and the Eaton Building, as well as the rebuilt Mara Gates at the main entrance. Two years later, the college changed its academic program to adopt the International Baccalaureate programme.

James FitzGerald, a former UCC student, published a book in 1994 called Old Boys; the Powerful Legacy of Upper Canada College. It caused some discussion in Canadian media because it showed an honest picture of life at the college. The book affected the school's internal structure and its relationship with the wider community.

The Eaton Building was made bigger in 1999 to add grades 1 and 2. Senior kindergarten was introduced in 2003.

New Millennium Focus

Early in the new millennium, UCC started focusing on environmentalism. In 2002, the board of governors decided to create the Green School initiative. This meant that environmental education would become a key part of a UCC education. It would include learning about ecology, environmental ethics, and how to help society. The school also planned to upgrade its buildings to be more environmentally friendly.

UCC Cadets

We don't know the exact date the Upper Canada College Cadets started. However, students were willing to help defend against the 1837 rebellion in Upper Canada. Later in the 1800s, many schools believed that military training taught young men patriotism, discipline, and obedience.

By 1863, UCC students practiced drills weekly. In 1865, with the start of the Fenian troubles, UCC students asked to form a company of The Queen's Own Rifles of Canada. By 1866, this request was granted, making UCC possibly the second school in Canada to have a proper Cadet Corps.

When the Fenians attacked Fort Erie, Ontario, on June 1, 1866, the UCC Cadets were called to duty. They were told to guard armories and official stores. This was the only time in Canadian military history that student Cadet Corps were called to active duty.

By the 1890s, interest in the Cadets had decreased. It cost extra money for uniforms and weapons, and the drills took time away from schoolwork and sports. Enrollment went up and down. By 1910, the number of Cadets increased to 63. During the First World War, many UCC students joined the Cadets.

Around 1919, joining the UCC Cadets became mandatory. The principal asked for the Corps to be given "Colours" (special flags). The College Colour was given in 1921.

During the war, the Cadets' connection with the Queen's Own Rifles had ended. By 1927, the college decided to affiliate with the Queen's Own Rifles again.

For the next 30 years, the Cadets remained a part of school life. By the middle of the Second World War, boys practiced drills, learned about military law, and map reading. The biggest event of the school year was Battalion Inspection Day. Cadets wore special uniforms, including navy-blue uniforms, berets, and white gloves. Officers also wore a sword.

By the 1960s, belief in the Cadets was fading. Young people were less interested in strict discipline. In 1976, Principal Richard Sadlier ended the compulsory Cadet Battalion. He felt that the drills were not very relevant anymore.

In 1977, the voluntary Royal Canadian Army Cadets helped organize a military science course at UCC. However, by the mid-1980s, interest in this program had dropped. Today, UCC does not offer formal military training.

Diversity at UCC

UCC started accepting students from different backgrounds early in its history. The first Black student enrolled in 1831, the first Jewish student in 1836, and the first Indigenous student in 1840. Some Indigenous graduates from the Ojibway peoples of Upper Canada later studied at Dartmouth College and Harvard University.

By the late 1990s, the college became more diverse. In 1997, the daily Lord's Prayer was replaced with a prayer from different global faiths each day. In 2002, a student created the Diversity Council. This group of students organizes celebrations of Chinese, Jewish, and Ukrainian cultures, as well as Canadian cultural events.

UCC's website states that its boarding program welcomes students from all faiths and cultures. Each year, over 100 students from about 16 countries come together in this diverse environment.

Past Principals

- 1829–38: Rev. Joseph H. Harris

- 1839–43: Rev. John McCaul

- 1843–56: Frederick W. Barron

- 1857–61: Rev. Walter Stennett

- 1861–81: George Ralph Richardson Cockburn

- 1881–85: John Milne Buchan

- 1885–95: George Dickson

- 1895–1902: George R. Parkin

- 1902–17: Henry W. Auden

- 1917–35: William L. Grant

- 1935–42: Terence W.L. MacDermot

- 1942–48: Lorne M. McKenzie

- 1948–65: Rev. C.W. Sowby

- 1965–74: Patrick T. Johnson

- 1974–88: Richard H. Sadlier

- 1988–92: Eric Barton

- 1992–2004: J. Douglas Blakey

- 2004–2015: Dr. James Power

- 2016–present: S. James McKinney

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |