History of banking in the United States facts for kids

This article details the history of banking in the United States. Banking in the United States is regulated by both the federal and state governments.

Contents

- Early Banks in the United States

- National Banking System

- Investment Banks Emerge

- Early 1900s Banking Changes

- New Deal Banking Reforms

- Bretton Woods System (Post-WWII)

- Automated Teller Machines (ATMs)

- Nixon Shock (1971)

- Deregulation in the 1980s and 1990s

- Glass-Steagall Act Repealed

- Late 2000s Financial Crisis

- COVID-19 Pandemic

Early Banks in the United States

In the early 1800s, many smaller banks started in places like New England. Laws made it easy to open new banks. These banks helped business owners borrow money to start or grow their companies. Even though some banks mainly lent money to people they knew, they were usually strong and didn't fail often. This helped the U.S. financial system grow.

First Ideas for a National Bank

In 1781, during the American Revolution, the government created the Bank of North America in Philadelphia. It was the first bank allowed to print money for the whole country.

Robert Morris, a key leader at the time, wanted this bank to handle all the government's money. He believed a strong national bank, like the Bank of England, was needed. Before this, money printed during the war had lost most of its value. After the war, more state banks opened, like the Bank of New York in 1784.

In the late 1700s, the U.S. had only three banks, but many different types of money! People used English, Spanish, and French coins, plus money printed by states. The value of this money changed depending on where you were.

Some people thought a national bank and a United States Mint (where coins are made) were needed for the country to grow. They wanted one type of money for everyone. Others worried that a government-controlled bank would make people poor.

The First Bank of the United States

In 1791, the U.S. Congress created the First Bank of the United States. This bank was partly owned by the government and partly by private investors. It acted as the government's bank and also competed with state banks. When people brought state bank notes to the First Bank, it would ask the state banks for gold in return. This made it harder for state banks to print more money.

Because of this, many state banks didn't like the First Bank. So, when its 20-year charter (permission to operate) ended in 1811, Congress did not renew it.

After the War of 1812, the U.S. faced serious money problems and inflation (when prices go up a lot). The government found it very hard to borrow money. To fix this, the Second Bank of the United States opened in 1817.

President Jackson and the Bank

The Second Bank of the United States also had a 20-year charter, ending in 1836. It held the government's money, which made state banks jealous. Politics played a big role in the debate over renewing its charter.

President Andrew Jackson strongly disliked the Second Bank. He believed that giving so much power to one bank caused inflation and other problems. He made stopping the bank a main goal of his 1832 election campaign. Jackson especially targeted Nicholas Biddle, the bank's president.

In 1833, President Jackson ordered that government money be removed from the Bank of the United States. These funds were then put into various state banks, which some people called Jackson's "pet banks."

The "Free Banking" Era (1837–1863)

Before 1837, you needed a special law from the state government to open a bank. But in 1837, Michigan passed a law allowing anyone to open a bank if they met certain rules. New York followed with its "Free Banking Act" in 1838, and other states soon did the same.

These "free banks" could print their own money, backed by gold and silver coins. States set rules for how much money banks had to keep in reserve and what interest rates they could charge. From 1840 to 1863, all banking was done by these state-chartered banks.

At first, some of these banks were unstable, especially in Western states. Some were called "wildcat" banks because they printed money without enough security. This led to many bank failures during economic downturns. It was confusing because many different kinds of state bank notes were circulating, and their real value was often less than their face value. However, over time, most states developed more stable banking systems.

National Banking System

To fix the problems of the "Free Banking" era, Congress passed the National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864. These laws created a system of banks chartered (approved) by the federal government. This system aimed to create a national currency backed by U.S. government bonds. It also set up the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency to check and regulate these national banks.

Congress also put a 10% tax on money printed by state banks starting in 1865. This encouraged many state banks to become national banks. State banks also started using "checking accounts" more, which became a major source of their income. This led to what we call the "dual banking system," where new banks can choose to be chartered by either the state or federal government.

At first, national banks grew quickly, but state banks soon recovered as checking accounts became popular.

Investment Banks Emerge

Civil War Financing

During the American Civil War, banks worked together to help the federal government raise money for the war. Jay Cooke led a huge effort to sell government bonds to many investors, raising about $830 million. He personally helped raise about $1.5 billion for the government.

Growing Need for Money in the Gilded Age

As factories grew in the late 1800s, businesses needed more money to expand. This led to many new banks opening. By 1880, New England had one of the highest numbers of banks in the world.

Unlike commercial banks that take deposits and make loans, investment banks helped connect investors (people with money) with companies that needed capital. They didn't issue money or take deposits. They were like brokers, helping big projects like railroads and mining companies get the money they needed.

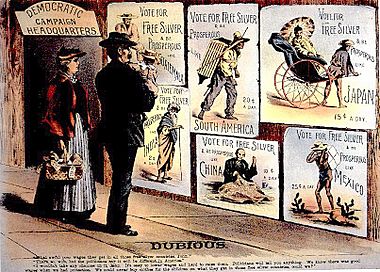

Gold Standard Debate

Toward the end of the 1800s, there was a big debate about what kind of money the U.S. should use. After the Civil War, the U.S. switched to using only gold to back its money (the "gold standard") in 1873. This made some people, called "silverites," very angry. They wanted to use both silver and gold to back money, believing it would increase the money supply and bring prosperity. They called the 1873 law "The Crime of '73."

The Panic of 1893, a severe economic downturn, made the money debate even bigger. Silverites argued that using silver would cause inflation, meaning more money for everyone. Gold supporters said that only a gold standard would bring back prosperity.

William Jennings Bryan became the leader of the Democratic Party in 1896 and strongly supported using silver. He gave a famous speech called the "Cross of Gold" speech. However, he lost the presidential election. One reason was that new ways to extract gold were discovered, increasing the world's gold supply and causing some of the inflation that silver supporters wanted.

Early 1900s Banking Changes

From 1890 to 1925, a few powerful investment banks, like J.P. Morgan & Co., controlled most of the industry. There were no laws separating commercial banks (which take deposits) from investment banks (which help companies raise money by selling stocks and bonds). This meant commercial banks could use their depositors' money to fund their investment banking activities.

The Panic of 1907 and the Pujo Committee

In 1913, a special committee called the Pujo Committee investigated how a small group of powerful bankers had gained control over many industries in the U.S. The committee found that leaders of J.P. Morgan & Co. also sat on the boards of many other large companies.

The Pujo Committee's report said that a few financial leaders controlled major manufacturing, transportation, mining, and financial markets. It showed that a small group of men controlled huge amounts of money through several banks.

These findings led to public support for important new laws: the Federal Reserve Act in 1913 and the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 in 1914.

The Federal Reserve System

The Panic of 1907 was a financial crisis that was stopped by a group of private banks lending money to other banks in trouble. This led to calls for a government agency to do the same thing.

In response, Congress created the Federal Reserve System in 1913. This new central bank was designed to be a "lender of last resort" to banks during financial panics. It would lend money to banks when depositors tried to withdraw all their money at once.

The Federal Reserve System includes several regional Federal Reserve Banks and a governing board. All national banks had to join, and state banks could join too. The Federal Reserve also started issuing "Federal Reserve notes" to provide a flexible supply of money for the nation.

Credit Unions Begin

Credit unions started in Europe in the mid-1800s. The first one in the U.S. opened in New Hampshire in 1908. At that time, many poor workers couldn't get loans from banks and had to go to unfair moneylenders.

A businessman named Edward Filene worked hard to get laws passed for credit unions, first in Massachusetts and then across the U.S. Credit unions were formed by groups of people who shared a common bond, like employees of the same company. Even though banks opposed them, the Federal Credit Union Act was signed into law in 1934. This allowed federal credit unions to be created. Today, there are thousands of credit unions in the U.S.

McFadden Act of 1927

The McFadden Act of 1927 aimed to make national banks equal to state-chartered banks. It allowed national banks to open branches within their state, but it stopped banks from opening branches across state lines. This rule was changed later in 1994.

Savings and Loan Associations

Savings and loan associations became important in the early 1900s. They helped people buy homes by offering mortgages. They also helped members save and invest money through savings accounts.

Early mortgages were often short-term with a large "balloon payment" at the end, or they were "interest-only" loans. This meant many people were always in debt or lost their homes if they couldn't make the final payment.

During the Great Depression, in 1932, Congress passed the Federal Home Loan Bank Act. This created the Federal Home Loan Bank to help other banks offer long-term, affordable home loans. The goal was to help more people own their homes. Savings and loan associations grew quickly because they could get low-cost funding from the Federal Home Loan Bank for mortgages.

New Deal Banking Reforms

In the 1930s, the U.S. and the world faced the Great Depression, a very bad economic crisis. In the U.S., unemployment reached 25%, and the stock market dropped 75%. Many banks failed, and people lost their savings because there was no insurance on deposits.

By early 1933, the U.S. banking system had almost stopped working. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office, he immediately worked with Congress to pass new laws.

Roosevelt blamed bankers for the crisis. In his first speech as president, he said:

Practices of the unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men. ... The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization.

Emergency Banking Act

Roosevelt closed all banks in the country for a short time until new laws could be passed. On March 9, 1933, Congress quickly passed the Emergency Banking Act. This law allowed sound banks to reopen under government supervision, with federal loans if needed. Most banks in the Federal Reserve System reopened within three days. Billions of dollars that people had hidden away flowed back into banks, helping to stabilize the system. By the end of 1933, many smaller banks had closed or merged.

FDIC and FSLIC Created

In June 1933, Congress created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). This agency insured bank deposits up to $2,500, meaning people wouldn't lose their money if their bank failed. The Banking Act of 1933 also:

- Made the FDIC a temporary government agency.

- Gave the FDIC power to insure deposits and regulate state banks.

- Provided money for the FDIC from the U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve.

- Put all commercial banks under federal oversight for the first time.

- Separated commercial banking from investment banking (the Glass-Steagall Act).

- Stopped banks from paying interest on checking accounts.

- Allowed national banks to branch statewide if state law permitted.

The FSLIC (Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation) was created in 1934 to insure deposits in savings and loan associations, similar to how the FDIC insured commercial banks.

Leaving the Gold Standard

To fight deflation (when prices fall), the U.S. stopped backing its money directly with gold. In 1933, the government ordered people to exchange large amounts of gold coins for U.S. dollars. The U.S. dollar was no longer directly tied to a fixed price in gold. This change helped the economy start to recover.

Glass-Steagall Act of 1933

The Glass–Steagall Act of 1933 was passed because many banks had failed. One of its main rules was to separate commercial banks (which take deposits and make loans) from investment banks (which help companies raise money by selling stocks and bonds). This meant large banks like JP Morgan had to split into separate companies. For example, JP Morgan continued as a commercial bank, while Morgan Stanley was formed as an investment bank.

Banking Act of 1935

The Banking Act of 1935 made the Federal Reserve Board of Governors stronger in managing credit. It also added more rules for banks and increased the FDIC's power to oversee banks.

Bretton Woods System (Post-WWII)

After World War II, in 1944, the Bretton Woods system was created. This system set up rules for how major industrial countries would handle money and trade. It was the first time countries agreed on a plan to manage the international money system.

The Bretton Woods system created the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which is now part of the World Bank Group. A key part of the system was that each country tied its currency's value to the U.S. dollar, and the U.S. dollar was tied to gold.

Automated Teller Machines (ATMs)

On September 2, 1969, Chemical Bank installed the first ATM in the U.S. in New York. These early ATMs gave out a set amount of cash when a special card was used. Chemical Bank advertised, "On Sept. 2 our bank will open at 9:00 and never close again." Bank leaders were unsure if customers would trust machines with their money.

Nixon Shock (1971)

In 1971, President Richard Nixon made big economic changes known as the Nixon shock. He stopped the U.S. dollar from being directly convertible to gold. This effectively ended the Bretton Woods system where the dollar was tied to gold.

Deregulation in the 1980s and 1990s

Laws passed in the 1980s, like the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980, made the differences between banks and other financial institutions less clear. This "deregulation" is sometimes blamed for the failure of over 500 savings and loan associations between 1980 and 1988.

Savings and Loan Crisis

The savings and loan crisis of the 1980s and 1990s saw 747 out of 3,234 savings and loan associations fail. The cost of fixing this crisis was about $87.9 billion. This crisis also contributed to an economic slowdown in the early 1990s.

FDIC Insurance Expands (1989)

Before 1989, only national banks had to have FDIC insurance. State banks could choose to get it. After 1989, all commercial banks that took deposits had to get FDIC insurance.

Interstate Banking

For a long time, national banks were not allowed to open branches in different states. This made them vulnerable to local economic problems. In 1994, the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994 changed this, allowing banks to operate across state lines.

Glass-Steagall Act Repealed

On November 12, 1999, parts of the Glass-Steagall Act were repealed by the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act. This meant that bank holding companies could now own other financial companies, removing the separation between investment banks and regular deposit-taking banks. Some experts believe this repeal contributed to the severity of the financial crisis of 2007–2008.

Late 2000s Financial Crisis

The late 2000s financial crisis is considered the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. It started with problems in the U.S. housing market, which caused the value of investments tied to real estate to drop sharply. This hurt financial institutions worldwide.

The crisis led to the collapse of large banks, governments having to bail out (help with money) banks, and stock markets falling around the world. It also caused a severe global economic recession. Many experts believe the crisis was caused by risky financial products and a lack of proper regulation. Governments and central banks responded with huge financial aid and new policies.

FDIC Insurance Expands Again (2008-2010)

During the 2008 financial crisis, Congress temporarily increased the FDIC insurance limit to $250,000 to encourage people and businesses to keep their money in banks. This increase became permanent in 2010 with the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act.

Dodd–Frank Act

The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act is the biggest change to financial rules in the U.S. since the Great Depression. It affects almost every part of the financial industry and aims to prevent another crisis.

COVID-19 Pandemic

On March 16, 2020, during the economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Federal Reserve reduced the amount of money banks were required to keep in reserve to 0%. This was the first time this had happened since the Federal Reserve was created.

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |