History of tea in Japan facts for kids

The history of tea in Japan started a very long time ago, around the 8th century. This is when the first mentions of tea appeared in Japanese records. Tea became a special drink for religious people in Japan. Japanese priests and visitors to China learned about its culture and brought tea back home. Two Buddhist monks, Kūkai and Saichō, might have been the first to bring tea seeds to Japan. The first type of tea from China was probably pressed blocks of tea. Tea then became popular with royal families when Emperor Saga encouraged growing tea plants. Seeds came from China, and tea farming began in Japan.

Tea became popular among noble families in the 12th century. This happened after Eisai wrote his book, Kissa Yōjōki. Uji, a place close to the capital city of Kyoto, became Japan's first big tea-growing area. From the 13th and 14th centuries, Japanese tea culture started to develop its unique style. The Japanese tea ceremony became a very important part of this culture.

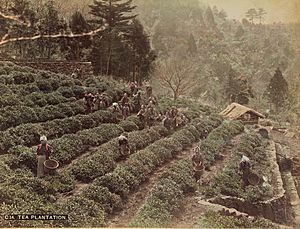

In the years that followed, more tea was grown, and it became a common drink for everyone. In the 18th century, a new type of tea called sencha was created. This led to new kinds of green tea that are very popular in Japan today. In the 19th and 20th centuries, machines helped the Japanese tea industry grow. This made it possible to make a lot of tea, even though Japan does not have much farm land.

Contents

How Tea First Came to Japan

The first time Japanese people likely encountered tea was in the 8th century. This was during the Nara period. Japan sent groups of people to Chang'an, the capital city of China's Tang dynasty. These groups brought back ideas about Chinese culture, along with art and books. One old book says that Emperor Shōmu served powdered tea to monks in 729. But we are not completely sure if this story is true.

In 804, two Buddhist monks, Kūkai and Saichō, traveled to China. They went to study religion as part of a government trip. A book written in 814 says that Kūkai drank tea while he was in China. He returned to Japan in 806. Kūkai was also the first to use the word chanoyu (茶の湯). This word later came to mean the Japanese tea ceremony. When they came back to Japan, Kūkai and Saichō started new Buddhist schools. People believe that one or both of them brought the first tea seeds to Japan on this trip. Saichō, who returned in 805, is often given credit for planting the first tea seeds in Japan. However, the old records are not completely clear.

A book called Kuikū Kokushi says that in 815, a Buddhist leader served tea to Emperor Saga. This is the earliest reliable record of tea drinking in Japan. After this, the emperor reportedly ordered five tea farms to be started near the capital city. Emperor Saga loved Chinese culture, and this included a passion for tea. He enjoyed Chinese poetry, which often praised the good things about tea. Emperor Saga's own poems, and those from his court, also mention drinking tea.

Later writings from this time show that Buddhist monks grew and drank tea in small amounts. They used it as part of their religious practices. The emperor's family and noble people also drank tea. But tea was not yet popular with everyone else. For about 300 years after Emperor Saga's death, interest in Chinese culture went down. So did the practice of drinking tea. Records from this time still said tea was good for medicine and as a pick-me-up. Some records even say it was drunk with milk, but this practice later stopped.

The tea drunk in Japan at this time was most likely brick tea (団茶, dancha). This was the common type of tea in China during the Tang dynasty. The world's first book about tea, Lu Yu's The Classic of Tea, was written before Kūkai and Saichō's time. In it, Lu Yu describes how to steam, roast, and press tea into bricks. He also explains how to grind the tea into powder and stir it into hot water. This method is thought to have led to how powdered matcha is made in Japan today.

Eisai and Making Tea Popular

The Zen monk Eisai is usually given credit for making tea popular in Japan. In 1191, Eisai came back from a trip to China. He brought tea seeds with him. He planted these seeds on Hirado Island and in the mountains of Kyūshū. He also gave some seeds to another monk, Myōe. Myōe was the leader of the Kōzan-ji temple in Kyoto. Myōe planted these seeds in Toganoo (栂尾) and Uji. These places became the first large tea farms in Japan. At first, Toganoo tea was thought to be the best in Japan. It was called "real tea" (本茶, honcha). Other teas were called "non-tea" (非茶, hicha). But by the 15th century, Uji tea became better than Toganoo tea. So, the terms honcha and hicha then meant Uji tea and non-Uji tea.

In 1211, Eisai wrote the first version of the Kissa Yōjōki (喫茶養生記, Drink Tea and Prolong Life). This was the first Japanese book about tea. The Kissa Yōjōki said that drinking tea was good for your health. It starts by saying, "Tea is the most wonderful medicine for nourishing one's health; it is the secret of long life." The beginning of the book explains how drinking tea can help the five main organs in your body. This idea comes from old Chinese medicine. Eisai believed that each organ liked different flavors. He thought that because tea is bitter, and "the heart loves bitter things," it would especially help the heart. Eisai then listed many supposed health effects of tea. These included helping with tiredness, indigestion, and heart problems. It also helped with thirst. The Kissa Yōjōki also explains what tea plants, flowers, and leaves look like. It tells how to grow tea plants and prepare tea leaves. The book did not say much about drinking tea just for fun. It focused on its health benefits.

Eisai was very important in introducing tea to the samurai class. He gave a copy of his Kissa Yōjōki in 1214 to the shōgun Minamoto no Sanetomo. Eisai also served tea to the young shōgun. Zen Buddhism, which Eisai and others taught, also became popular during this time. It was especially popular among the warrior class. The Zen monk Dōgen created rules for Buddhist temples. These rules were based on an old Chinese text. Dōgen's rules included how to serve tea in Buddhist ceremonies. Tea was seen as very important for people who practiced Zen Buddhism. Musō Soseki even said that "tea and Zen are one."

Soon, green tea became a common drink for educated people in Japan. It was a drink for noble families and Buddhist priests. More tea was grown, and it became easier to get. However, it was still mostly enjoyed by the upper classes.

Medieval Tea Culture

Tea Competitions and Fun

In the 14th century, tea competitions (鬥茶, tōcha) became a popular game. In these games, people tried to tell the difference between teas grown in different areas. They especially tried to tell the difference between honcha (real tea) and hicha (non-tea). These events were known for people making big bets. A samurai named Sasaki Dōyō was famous for holding these competitions. They had fancy decorations, lots of food and sake (rice wine), and dancing. This love for fancy and sometimes wild things was called basara (婆娑羅). Some writers at the time thought it was too much. People also loved Chinese objects (唐もの, karamono) during this time. These included paintings, pottery, and beautiful writing.

Tea Rooms and Early Tea Ceremonies

In the 15th century, Shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa built the first tea room in the shoin chanoyu style. This was a simple room in his retirement home at Ginkaku-ji. It allowed the shōgun to show off his karamono (Chinese objects) when he held tea ceremonies. The shoin style room came from the study rooms of Zen monks. They had tatami mats covering the whole floor, unlike earlier plain wooden floors. They also had a shoin desk built into the wall. These rooms were like the first versions of modern Japanese living rooms. The simple style of this new tea room (茶室, chashitsu) was a step towards the formal chanoyu tea ceremony that came later.

It is said that Yoshimasa's tea teacher was Murata Shukō. Shukō is known for creating the quiet, "cold and withered" style of the Japanese tea ceremony. He suggested mixing imported Chinese items with rough pottery made in Japan. He wanted to "make Japanese and Chinese tastes work together." This idea of using simple or imperfect tools with a wabi feeling came to be called wabicha. Shukō, however, did not fully support a completely wabi way of doing chanoyu. In contrast, Takeno Jōō, who learned from one of Shukō's students, worked hard to develop the wabi style. This included both tea tools and the way the tea room was decorated.

The Japanese Tea Ceremony

Sen no Rikyū and Tea

The most important person in making the Japanese tea ceremony what it is today was Sen no Rikyū. Rikyū was the tea master for two powerful leaders, daimyos Oda Nobunaga and Toyotaka Hideyoshi. He lived during a time of big changes in Japan, called the Sengoku period. During this time, society and government were changing a lot. Rikyū grew up in Sakai, where rich merchants had a lot of power. They helped shape Japanese tea culture. Rikyū, whose father was a fish merchant, learned about tea from Takeno Jōō. Like Jōō, he liked the wabi style of tea.

At this time, the tea ceremony was very important in politics and talking between leaders. Nobunaga even stopped anyone but his closest friends from doing it. The simple wabicha style that Rikyū liked was not as popular for these political meetings. People preferred a more fancy style. After Nobunaga died, Sen no Rikyū worked for Hideyoshi. He built a simple wabi tea hut called Taian. This became one of Hideyoshi's favorite tea rooms. Rikyū chose a thatched roof, which was different from the shingled roofs others liked. This room is called the "North Pole of Japanese aesthetics." It shows the simple wabi style that became very important in Japanese tea culture. Besides the simple tea room, Rikyū also set the rules for how the modern tea ceremony should be done. He chose the steps and the tools to use. He also created the nijiriguchi, a small entrance that guests had to crawl through to get into the tea room.

Even though Hideyoshi forced Rikyū to commit seppuku in 1591, Rikyū's family was allowed to continue their work. The three main schools of the traditional Japanese tea ceremony today are the Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushakōjisenke. All of them were started by children of Sen no Sōtan, who was Rikyū's grandson.

Tea Tools and Pottery

Changes in the Japanese tea ceremony during the Sengoku period led to new styles of Japanese tea tools. Rikyū's student Furuta Oribe became Hideyoshi's tea master after Rikyū died. Oribe liked green and black glazes and uneven shapes. This led to a new style of pottery called Oribe ware. Rikyū also changed Japanese tastes in pottery. He did not like the smooth, regular Chinese-style tenmoku pottery. Instead, he preferred uneven rice bowls made by Korean potters in Japan. This style of tea bowl, or chawan, was called raku ware. It was named after the Korean potter who made the first pieces for Rikyū's tea ceremonies. Raku ware is known for its simple, wabi look and feel.

Matcha Tea

Modern Japanese matcha is made by grinding loose, dry tea leaves into a powder. This is different from the pressed tea bricks that first came from China. Matcha has a sweet taste and a deep green color. This is because the tea leaves are covered from the sun in the last few weeks before they are picked. This increases the chlorophyll and lowers the tannin in the leaves. This method started in the 16th century among tea growers in Uji. It is also used to make gyokuro tea.

Edo Period Tea Changes

During Japan's Edo period (1603–1868), new types of tea appeared. This also brought new ways of enjoying tea. Influenced by China's Ming dynasty, loose leaf tea became a choice instead of powdered tea. This led to the creation of sencha.

The Rise of Sencha

By the 14th century, drinking powdered brick tea was no longer popular in China. Instead, most tea was dried by hand in a dry wok. This stopped the tea from changing color and flavor. The tea was then bought as loose leaves, not pressed bricks. At first, these loose leaves were still ground into a powder and mixed with hot water. But by the late 16th century, tea lovers were steeping the leaves in hot water in teapots. Then they poured the tea into teacups. This new way of making and drinking tea arrived in Japan in the 17th century. People who liked this new way, especially the monk Baisao, did not like the strict rules of the traditional Japanese tea ceremony. That ceremony was based on the older powdered tea methods. Instead, they wanted a relaxed, informal way to drink tea. This was inspired by old Chinese wise people.

The method of steeping loose tea leaves in hot water became known as "boiled tea" (煎茶, sencha). This soon led to a new way of making green tea that worked well with this method. In 1737, a tea grower from Uji named Nagatani Sōen created the process we use today for making leaf teas in Japan. First, tea leaves are steamed. Then they are rolled into thin needles and dried in an oven. This process gives the leaf a bright green color and a "clean," sometimes sweet, taste. Nagatani's tea caught the eye of Baisao. It became known by the same name as the sencha method of steeping tea. Sencha grew in popularity over time. It is now the most popular type of tea in Japan, making up 80 percent of all tea produced each year.

Modern Tea Making

At the end of the Meiji era (1868–1912), machines started to make green tea. This began to replace tea made by hand. Machines took over steps like drying, rolling, and steaming the tea.

In the 20th century, machines helped improve tea quality and reduce the need for human labor. Sensors and computer controls were added to tea machines. This means that even workers without special skills can make excellent tea without losing quality.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del té en Japón para niños

In Spanish: Historia del té en Japón para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |