History of the Irish language facts for kids

|

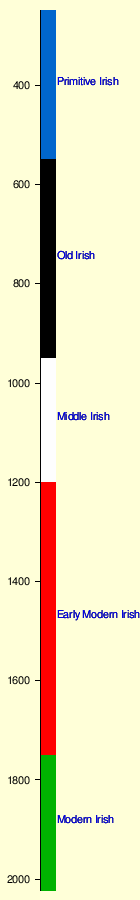

The history of the Irish language tells us how this ancient language has changed over time. It all started when people speaking Celtic languages arrived in Ireland. The very first known form of Irish is called Primitive Irish. We find it on Ogham inscriptions from around 300 or 400 AD.

After Ireland became Christian in the 5th century, Old Irish started to appear. It was often written as notes in the margins of Latin books. This began in the 6th century. By the 10th century, Old Irish changed into Middle Irish. Then, Early Modern Irish acted as a bridge between Middle Irish and Modern Irish.

A special written form, Classical Gaelic, was used by writers in both Ireland and Scotland until the 1700s. After that, writers began using local ways of speaking, like Ulster Irish, Connacht Irish, and Munster Irish. In the 19th century, under British rule, fewer people wrote in Irish. It became mostly a spoken language.

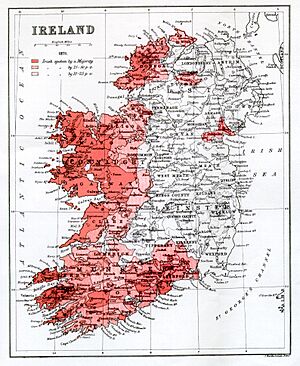

The number of Irish speakers also went down a lot during this time. Many people started speaking only English. Even though Irish never completely disappeared, it was mostly spoken in rural and remote areas by the late 1800s. This changed with the Gaelic Revival movement. In the 20th and 21st centuries, Irish continues to be spoken in special areas called Gaeltacht regions. It is also spoken by some people in other parts of Ireland. Today, Irish is seen as a very important part of Ireland's culture. Many people are working to keep it alive and help it grow.

Contents

Early History of Irish

The languages that are part of the Indo-European languages family might have arrived in Ireland a very long time ago. This was between 2400 BC and 2000 BC. It happened when the Bell Beaker culture spread across Europe. About 90% of the people living in Ireland at that time were replaced by new groups. These new groups were related to the Yamnaya culture from the Pontic steppe.

Some experts think the Bell Beaker culture might be linked to early Proto-Indo-Europeans. These were the first speakers of the Indo-European languages. One idea is that the Bell Beaker culture was connected to a group of Indo-European languages in Europe. These languages eventually led to Celtic, Italic, Germanic, and Balto-Slavic languages.

Primitive Irish Language

Primitive Irish is the oldest written form of the Irish language we know about. We only have small pieces of it, mostly names. These names are carved into stones using the Ogham alphabet. The very first of these carvings probably date back to the 3rd or 4th century AD.

You can find Ogham inscriptions mainly in the south of Ireland. They are also found in Wales, Devon, Cornwall, and the Isle of Man. Irish settlers brought these inscriptions to those areas a long time ago.

Old Irish Language

Old Irish was the first language written down in Europe north of the Alps. It first appeared in the margins of Latin manuscripts. This happened as early as the 6th century. Old Irish can be split into two periods. The first is Early Old Irish, or Archaic Irish, from around the 7th century. The second is Old Irish itself, from the 8th to 9th centuries.

One very important Old Irish text was the Senchas Már. This was a collection of early legal writings. People say it was put together from older, pre-Christian writings by Saint Patrick. Many stories from the Ulster Cycle were written later in the Middle Irish period. However, many of their heroes were first described in Old Irish texts. Many early Irish stories, even if written down in Middle Irish books, are actually in the style of Old Irish.

Middle Irish Language

Middle Irish was the form of Irish spoken and written from the 10th to the 13th centuries. This means it was used at the same time as late Old English and early Middle English. Middle Irish writing shows more differences in language compared to the very consistent writing of Old Irish. In Middle Irish texts, writers often mixed old and new ways of speaking in the same piece of writing.

A lot of important literature was written in Middle Irish. This includes all the stories of the famous Ulster Cycle.

Early Modern Irish Language

Early Modern Irish was used from about 1200 to 1600. It was a bridge between Middle Irish and Modern Irish. Its formal written style was called Classical Gaelic. This style was used in both Ireland and Scotland from the 13th to the 18th century.

The rules for Early Modern Irish grammar were written down in special books. These books were created by native speakers. They were meant to teach the best form of the language to students. These students included poets, lawyers, doctors, and monks in Ireland and Scotland.

Irish in the 19th and 20th Centuries

It is thought that Irish was the main language in Ireland until about 1800. But during the 19th century, it became a minority language. Still, it remained a very important part of Irish nationalist identity. It showed a cultural difference between Irish people and the English.

Several things caused the decline of Irish. State-funded primary schools, called National Schools, started in 1831. Irish was not taught in these schools until 1878. Even then, it was only an extra subject, taught after English, Latin, Greek, and French. The Roman Catholic Church also ran many National Schools. They discouraged the use of Irish until around 1890.

The Great Famine (called An Drochshaol in Irish) hit Irish speakers very hard. They often lived in poorer areas that suffered greatly from deaths and people moving away. This led to a very fast decline in the language.

Some Irish political leaders, like Daniel O'Connell, also thought Irish was "backward." They saw English as the language of the future. Many Irish people found better jobs in the British Empire and the United States of America. Both of these places used English. Reports from that time say that Irish-speaking parents often told their children to speak English instead. This idea that speaking Irish was "old-fashioned" continued even after Ireland became independent.

However, many Irish speakers in the 19th century insisted on using their language. They used it in law courts, even if they knew English. It was common for interpreters to be used. Many judges, lawyers, and jury members also knew Irish. Being able to speak Irish was often helpful in business. Political leaders found the language very useful. Irish was also a key part of changes in Catholic religious practices. Catholic bishops made sure there were enough Irish-speaking priests. Irish was widely used in local schools, even if not officially. Until the 1840s and beyond, Irish speakers could be found in all kinds of jobs.

The first efforts to bring Irish back were led by Anglo-Irish Protestants. One example was William Neilson in the late 1700s. The biggest push came with the creation of the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge) in 1893. This group was started by Douglas Hyde, whose father was a Church of Ireland rector. The Gaelic League helped start the Irish Revival movement. By 1904, the League had 50,000 members. They also successfully pushed the government to allow Irish to be taught in schools that same year. Important supporters included Pádraig Pearse and Éamon de Valera.

This renewed interest in the language happened at the same time as other cultural revivals. The Gaelic Athletic Association was founded. Plays about Ireland, written in English by famous writers like W. B. Yeats and J. M. Synge, became popular. They helped launch the Abbey Theatre. By 1901, only about 641,000 people spoke Irish. Only about 20,953 of them spoke only Irish. This big change was due to the Great Famine and the pressure to speak English.

Even though Abbey Theatre writers wrote in English, the Irish language influenced them. The way English is spoken in Ireland, called Hiberno-English, has some grammar similar to Irish. Writers like J.M. Synge, Yeats, and George Bernard Shaw used Hiberno-English. More recently, Seamus Heaney and Paul Durcan have used it too.

This cultural revival in the late 19th and early 20th centuries matched a growing desire for Irish independence. Many people who fought for Irish independence and later governed the country first became interested in politics through the Gaelic League. Douglas Hyde had talked about "de-anglicizing" Ireland. This was a cultural goal, not a political one. Hyde left the Gaelic League in 1915. This was because the group voted to join the movement for independence. The group had been joined by members of the secret Irish Republican Brotherhood. It changed from a cultural group to one with strong nationalist goals.

A Church of Ireland group, Cumann Gaeilge na hEaglaise, started in 1914. It aimed to promote worship in Irish. The Roman Catholic Church also began using Irish and English in its services after the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s. The first full Irish Bible was published in 1981. In 1982, the song "Theme from Harry's Game" by Clannad became the first song with Irish lyrics to appear on Britain's Top of the Pops.

It is thought that about 800,000 people spoke only Irish in 1800. This number dropped to 320,000 after the Famine. By 1911, it was under 17,000.

Irish in the 21st Century

In July 2003, the Official Languages Act was signed into law. This law made Irish an official language of Ireland. It means that public services must be available in Irish. This includes things like advertising, signs, announcements, and public reports.

In 2007, Irish also became an official working language of the European Union. This was a big step for the language on the international stage.

Independent Ireland and the Language

The independent Irish state was formed in 1922. Even though some leaders were very keen on the language, the new state kept using English for government work. This happened even in areas where over 80% of people spoke Irish. There was some early excitement. In March 1922, a rule was passed that Irish names had to be used on birth, death, and marriage certificates. But this rule was never put into action, probably because of the Irish civil war.

Areas where Irish was still widely spoken were officially called Gaeltachtaí. The idea was to protect the language there and then help it spread. However, the government did not follow the advice of the 1926 Gaeltacht Commission. This commission suggested using Irish for government work in these areas. As the government grew, it put a lot of pressure on Irish speakers to use English.

This was only partly balanced by efforts to support Irish. For example, the government was the biggest employer. You needed an Irish qualification to apply for government jobs. But this did not mean you had to be very fluent. Few public employees ever had to use Irish for their work. Instead, they needed to be perfect in English and used it all the time. Because most public employees were not good at Irish, it was hard to deal with them in Irish. If an Irish speaker wanted a grant or to complain about taxes, they usually had to do it in English. A report in 1986 said that government agencies were "among the strongest forces for Anglicisation in Gaeltacht areas."

The new state also tried to promote Irish through schools. Some politicians thought the country would mostly speak Irish within a generation. In 1928, Irish became a required subject for the Intermediate Certificate exams. It became required for the Leaving Certificate in 1934. But many agree that this policy was not well carried out. From the mid-1940s, the idea of teaching all subjects in Irish to English-speaking children was stopped. In the years that followed, support for the language slowly decreased.

Irish has gone through changes in spelling and writing style since the 1940s. These changes were made to make the language simpler. The old Irish writing style fell out of use. These changes were not popular with everyone. Many people felt that these changes meant losing part of Irish identity. Another reason for the negative reaction was that current Irish speakers had to re-learn how to read Irish.

It is debated how much leaders like de Valera truly tried to make Irish the main language in politics. Even in the first Dáil Éireann (Irish parliament), few speeches were given in Irish, except for formal parts. In the 1950s, An Caighdeán Oifigiúil (The Official Standard) was created. This simplified spellings and helped different dialect speakers understand each other. By 1965, some politicians in the Dáil regretted that people taught Irish in the old style were not helped by the change to the new style. A group called the "Language Freedom Movement" started in 1966. They were against making Irish compulsory. But this group mostly disappeared within ten years.

Overall, the number of people who speak Irish as their first language has gone down since independence. However, the number of people who speak it as a second language has gone up.

There have been some good things happening for the language recently. These include the Gaelscoileanna (Irish-medium schools) movement, the Official Languages Act 2003, the TV channel TG4, and the radio station RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta.

In 2005, Enda Kenny, who used to be an Irish teacher, suggested that Irish should not be compulsory after the Junior Certificate level. He thought it should be an optional subject for the Leaving Certificate. This caused a lot of discussion. The Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Bertie Ahern argued that it should stay compulsory.

Today, estimates say there are between 40,000 and 80,000 native Irish speakers. In the Republic of Ireland, over 72,000 people use Irish daily outside of school. A larger group of people are fluent but do not use it every day. While census figures show that 1.66 million people in the Republic know some Irish, many only know a little. Smaller numbers of Irish speakers live in Britain, Canada (especially Newfoundland), the United States, and other countries.

A big change in recent years has been the rise in urban Irish speakers. This group is often well-educated and middle-class. They mainly come from independent schools called gaelscoileanna at primary level. These schools teach everything through Irish. These schools do very well academically. Studies show that 22% of Irish-medium schools sent all their students to university. This is compared to 7% of English-medium schools. Since the number of traditional speakers in the Gaeltacht areas is going down, it seems the future of the language might be in cities. Some people think that being fluent in Irish, with its social and job benefits, might now be a sign of an urban elite. Others argue that it is simply that middle-class people, for cultural reasons, are more likely to speak Irish. It is estimated that the active Irish-language community, mostly in cities, could be as much as 10% of Ireland's population.

Irish in Northern Ireland

Since Ireland was divided, the way the language has developed in the Republic and Northern Ireland has been very different. Irish is the official first language in the Republic. But in Northern Ireland, the language only gained official status a century after the division, with the Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act 2022.

Irish in Northern Ireland declined quickly during the 20th century. The traditional Irish-speaking communities were replaced by people learning the language and by Gaelscoileanna. A recent interesting development is that some Protestants in East Belfast have shown interest in Irish. They found out that Irish was not just a Catholic language. Protestants, especially Presbyterians, also spoke it in Ulster. In the 19th century, being fluent in Irish was sometimes needed to become a Presbyterian minister.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |