History of the MBTA facts for kids

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA), often called "The T," is Boston's public transportation system. Its history goes back over 200 years, starting with some of the oldest railroads in the United States. Public transport helped Boston grow and change over time.

For a long time, private companies ran Boston's transportation. This included ferries, steamships, trains, horse-drawn streetcars, and electric streetcars. They also built elevated trains and subways. Many streetcar lines joined together to form the West End Street Railway in 1887. This company then became the Boston Elevated Railway (BER) in 1897. That same year, the BER opened the first subway in the United States, called the Tremont Street subway. The city paid for the subway, and a group called the Boston Transit Commission managed it.

As cars became more popular, public transport companies started losing money. So, in 1947, the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) took over the BER. The MTA began replacing some train services with faster subway lines. In 1963, the MTA also started running ferry services.

The MBTA took over from the MTA in 1964. It expanded to include all the commuter train services in the area. These train lines had to be taken over by the government or stopped because they were losing money. Special services for people with disabilities, called Paratransit, began in 1977.

Most streetcars were replaced by buses, except for the Mattapan Line and parts of the Green Line. In the 1970s, people started focusing less on building highways and more on public transport. This led to changes like moving part of the Orange Line. As more people moved back to cities and the population grew, the need for public transport increased.

The MBTA kept adding and reopening commuter train lines. They also expanded the subway system in the late 1900s and early 2000s. A huge construction project called the Big Dig (1991-2006) led to the creation of the Silver Line (a bus-subway line). It also promised other expansions to help with pollution from more highways.

In 2000, the way the MBTA was funded changed. Instead of getting money for past expenses, they got a fixed budget. This budget came from 1% of the state's sales tax and money from cities and towns. However, sales tax money was lower than expected, partly because more people shopped online. Also, the MBTA had to pay for Big Dig transit projects, which caused money problems. They sometimes needed extra money from the state. In 2009, the MBTA became part of the new MassDOT (Massachusetts Department of Transportation).

From 2015 to 2023, during Governor Charlie Baker's time, the subway system had many problems because maintenance had been put off. A big snowstorm in 2015 even shut down two subway lines. This led to a special board being put in charge temporarily. After the COVID-19 pandemic, there were many safety problems. This caused the Federal Transit Administration to investigate in 2022, and the MBTA had to cut some services for safety reasons.

Contents

Early Public Transport

Public transportation in Boston, Massachusetts began around 1630. This was when a family started a ferry service. Land transportation in Boston began in 1793 with a private stagecoach service.

Steam Trains

Steam trains became useful for public transport in the 1810s. They arrived in the United States in the 1820s. Three major train lines were built from Boston to other industrial cities between 1834 and 1835. These were the Boston and Lowell Railroad, Boston and Worcester Railroad, and Boston and Providence Railroad. Soon, there were eight main lines and many smaller branches going out from Boston.

By the late 1800s, these lines were mostly owned by three big companies: the Boston and Maine Railroad (B&M), the New York Central Railroad, and the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad. Many smaller branches closed between the 1910s and 1950s. But seven main lines and some branches still carried passengers when the MBTA started in 1964.

The B&M operated lines like the Newburyport/Rockport Line, Haverhill Line, Lowell Line, and Fitchburg Line. The Boston and Albany Railroad, which became part of the New York Central, ran the line to [[{{{station}}} (MBTA station)|{{{station}}}]]. The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad operated many lines, including the Providence/Stoughton Line, Fairmount Line, Franklin/Foxboro Line, and Needham Line.

Before the MBTA was formed, the New Haven company stopped service on many of its lines. However, some of these lines, like the Kingston Line, Middleborough/Lakeville Line, and Greenbush Line, were later reopened by the MBTA.

Another important line was the Boston, Revere Beach and Lynn Railroad. It opened in 1874 and ran from East Boston to Lynn. This was a special narrow-gauge train line. It was electrified in 1928, meaning it ran on electricity. All service on this line ended in 1940. Later, parts of its path in East Boston and Revere were turned into a subway line, which is now part of the Blue Line.

Streetcar Era

The Cambridge Railroad was the first streetcar company in Massachusetts. It started in 1853 to connect the West End of Boston to Central Square and Harvard Square in Cambridge. This was the same path that today's Red Line subway follows, but it was on the street. Horse-drawn streetcars began running on March 26, 1856. Soon, over 20 streetcar lines were built across the Boston area by different companies.

To control prices and reduce competition, a law was passed to combine these train lines. This created the West End Street Railway in 1885. This company took over many existing streetcar lines in Boston and nearby towns. They started changing the horse-drawn cars to electric ones. The first electric trolleys ran in 1889, and the last horse-drawn car stopped around 1900.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, two other streetcar companies, the Middlesex and Boston Street Railway and the Eastern Massachusetts Street Railway, also took over many smaller lines in the suburbs.

Subways and Elevated Trains

Streets in downtown Boston became very crowded with streetcars. This, along with a big snowstorm in 1888, showed the need for subways and elevated trains. These special railways would be separate from street traffic. This would allow more people to travel and avoid delays. The West End Street Railway changed its name to the Boston Elevated Railway (BERy) and started these projects.

Boston's subway was the first in the United States. It is often called "America's First Subway." In 1897 and 1898, the Tremont Street subway opened. This became the main part of what is now the Green Line.

In 1901, the Main Line Elevated opened. This was an elevated train line that ran above ground in outer areas. It used the Tremont Street subway downtown. This was Boston's first elevated railway and first rapid transit line.

In 1904, the East Boston Tunnel opened. This was a streetcar tunnel that went under Boston Harbor to East Boston. It replaced a ferry service. In 1924, the tunnel was changed to handle faster subway trains.

In 1908, the Washington Street Tunnel opened. This gave the elevated trains a shorter route through downtown. The older Tremont Street subway then went back to being fully used by streetcars. More extensions and branches were built for the Tremont Street subway.

In 1912, the Cambridge Tunnel opened, connecting downtown Boston to Harvard Square in Cambridge. It was later extended south to Dorchester as the Dorchester Tunnel. This line was extended further in stages from 1927. The Ashmont–Mattapan High Speed Line continued along an old train path to Mattapan. These new subway lines caused some streetcar services to be shortened.

Many of the main subway stations were "prepayment stations." This meant you could transfer for free between streetcars and the subway or elevated lines. This was possible because one company ran all the services. Today, fare gates are at all subway stations, but not most above-ground Green Line stops.

Free transfers inside stations were stopped in 1961, except for transfers between subway lines downtown. Transfers between buses and subways were brought back in a limited way in 2000 and fully in 2007, if you used a CharlieCard. Transfers between buses are free, but bus to subway transfers cost less, not free.

Mid-1900s Changes

Streetcars and Trains Decline

The Boston Elevated Railway started replacing trains with buses in 1922. This process was sometimes called "bustitution." The last Middlesex and Boston Street Railway streetcars ran in 1930. The BERy also started using electric buses, called trackless trolleys, in 1936.

By 1953, only a few streetcar lines were left. They mostly ran into two tunnels: the main Tremont Street subway downtown and a short tunnel in Harvard Square. Diesel buses could not be used in these tunnels because of their exhaust fumes.

In 1958, the Harvard Square tunnel routes were replaced with electric trackless trolleys. These are the only ones the MBTA still uses.

The old elevated train lines became a problem. They were ugly, noisy, and had sharp turns that made trains go very slowly. The Atlantic Avenue Elevated line was damaged in the Great Molasses Flood of 1919. After another accident in 1928, it was partly closed. It was completely shut down in 1938 and taken apart for scrap metal in 1942.

In 1944, passenger service on the Fairmount Line was stopped because fewer people were riding it. As train passenger service became less profitable, mostly because cars were so popular, the government had to take over to keep commuter train services from closing down.

MTA Takes Over

In 1947, the new Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) bought and took over the subway, elevated, streetcar, and bus services from the Boston Elevated Railway. The MTA served 14 cities and towns, including Boston, Cambridge, and Newton.

A state group suggested a big plan in 1947. They wanted to replace private commuter train services, which were losing money, with faster electric subway lines. These lines would go out to areas like Massachusetts Route 128. The goal was to get people to use public transport instead of cars to help with "terrible traffic in downtown Boston."

The MTA did expand some subway lines. But progress slowed as more people bought cars, and a 1956 law encouraged building highways.

Between 1952 and 1954, the Revere Extension (now part of the Blue Line) opened. It went to Wonderland, mostly along the path of the old narrow-gauge Boston, Revere Beach and Lynn Railroad.

In 1959, MTA streetcar service opened on what is now the Riverside Green Line D branch. It connected to the Boylston Street subway and used tracks bought from the New York Central Railroad. This new service was very popular and needed many more streetcars than expected.

Also in 1959, when the Southeast Expressway opened, the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad stopped passenger service on its old lines. The new subway service that replaced it did not open until 12 years later.

The last two streetcar lines that went into the Pleasant Street Portal of the Tremont Street subway were replaced with buses in 1953 and 1962. That subway entrance is now covered by a park.

When the MTA brought back year-round ferry service to Hull in 1963 (now MBTA boat), it was the only ferry service in the United States focused on daily commuters.

MBTA Begins

Formation and Commuter Train Takeovers

On August 3, 1964, the MBTA took over from the MTA. Its service area grew to 78 cities and towns.

The MBTA was created partly to help pay for existing commuter train services. These were run by three private companies. The MBTA soon started paying these companies to keep services running. From 1973 to 1976, the MBTA bought most of the commuter train tracks and trains. However, many services were cut back. Since then, many of these lines have reopened, especially the Old Colony Railroad lines to the South Shore.

By 1964, commuter train service to Worcester was running. In 1965, the Boston and Maine Railroad started getting money from the MBTA for its commuter service. In 1973, the MBTA bought most of its current commuter train tracks from the Boston and Maine Railroad and Penn Central. They also bought trains at this time. The tracks between Framingham and Worcester were not bought by the MBTA. Because there was no state money, commuter train service on this part was cut in 1975. Service started again in 1994. The Fairmount Line was bought in 1976. Passenger service there started again in 1979.

Bus Expansion and Streetcar Cuts

In 1965, the MBTA gave colors to its four subway lines. They also gave letters to the Green Line branches. However, there weren't enough streetcars, so buses replaced train service on two Green Line branches. In 1969, the entire A branch was replaced by buses. In 1985, the part of the E branch from Heath Street to Arborway was also replaced by buses.

In 1968, the MBTA bought bus routes in the outer suburbs from other companies. They bought more western suburban routes in 1972. Like the commuter train system, many of the far-out bus routes were stopped because not many people used them, they cost too much to run, or towns outside the main district didn't want to join the MBTA.

Subway Expansion

In the 1970s, the MBTA got a boost when a study looked at how important public transport was compared to highways. After a pause on building major highways, many transit lines were planned for expansion.

The Charlestown Elevated, part of the Orange Line north of downtown Boston, was replaced by the Haymarket North Extension in 1975.

The Braintree extension, a branch of the Red Line to Braintree, opened in stages from 1971 to 1980. This improved an existing train path. The Red Line Northwest Extension to Alewife opened in 1985. Part of it followed an old train path, and part was a new deep tunnel.

The southern part of the Washington Street Elevated lasted until 1987. Then, the Southwest Corridor opened. This moved the Orange Line service from the old elevated tracks to new facilities next to an existing train path. The closing of the Washington Street Elevated meant that the Roxbury neighborhood no longer had subway service. This was later replaced by the Silver Line bus rapid transit.

These expansions not only added more subway coverage but also built large parking garages at several stations. For example, the Route 2 highway ends at the Red Line's last stop, Alewife station, which has a big parking garage.

In 2004, the Causeway Street Elevated was replaced by a subway tunnel. Now, the only elevated train lines left are a short part of the Red Line at Charles/MGH and a short part of the Green Line between Science Park and Lechmere.

2000s and Beyond

MBTA Expansion and the Big Dig

In 1999, the MBTA's service area grew even more to 175 cities and towns. This included most communities served by or near commuter train lines. The MBTA did not take over local bus services in these towns.

Before July 1, 2000, the state of Massachusetts automatically paid the MBTA for all costs that were more than the money it collected. After that date, the MBTA got a fixed amount of money. This came from a special 20% part of the state's 5% sales tax and money from the cities and towns it served. From then on, the MBTA had to manage within this "forward funding" budget.

The state also made the MBTA responsible for increasing public transport. This was to make up for more car pollution from the Big Dig project. The MBTA buried part of the Green Line and rebuilt Haymarket and North Stations during the Big Dig. However, the Big Dig project did not include money for these improvements. This put a lot of pressure on the MBTA's limited funds. Since 1988, the MBTA has been the fastest-growing transit system in the country.

When the MBTA's budget became limited in 2000, the agency started to go into debt. This was from planned projects and required Big Dig work. The MBTA now has the highest debt of any transit authority in the country. To help with this, prices for rides went up a lot on January 1, 2007. Many local groups are asking the state to take over some of the MBTA's debt. The interest on this debt takes up a large part of the MBTA's yearly money. This limits how much money is left for other important projects.

In 2006, the MetroWest Regional Transit Authority was created. This meant some towns could pay their transit money to this new group instead of the MBTA. The MBTA still got the same amount of money overall, but the other cities and towns had to pay more. On October 31, 2007, the MBTA brought back commuter train service to the Greenbush section of Scituate. This was the third branch of the Old Colony service to reopen.

Train track repairs on the Green Line D branch happened in the summer of 2007. New, low-floor streetcars were introduced on this line on December 1, 2008.

In 2008, Daniel Grabauskas, who was the MBTA General Manager at the time, said that the MBTA had been secretly cutting trips from its published train and bus schedules for years. He said this practice had stopped.

On June 26, 2009, Governor Deval Patrick signed a law that put the MBTA under the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT). The MBTA became part of the Mass Transit division.

Rhode Island has paid for commuter train service to Providence since 1988. They paid for extensions of the Providence/Stoughton Line to T.F. Green Airport in 2010 and Wickford Junction in 2012. The Fairmount Line, which is entirely in southern Boston, has been improved since 2002. The first new station, Talbot Avenue, opened in November 2012.

Debt and Fare Increases

Some groups have said that since 1988, the MBTA has been the fastest-growing transit system in the country. However, other research shows that the MBTA is not the fastest-growing in most areas, but it is among the top 10 for how much ridership has grown.

When the MBTA's income was capped in 2000, the agency started to build up large debts. This was from projects already planned and required Big Dig work. As of 2012, the MBTA had the highest debt of any transit authority in the United States. To try and fix this, fares were increased on January 1, 2007. For example, a subway ride with a CharlieTicket went from $1.25 to $2.00. Many local groups are asking the state to take over some of the MBTA's debt, which was about $9 billion. The interest on this debt is a huge part of the MBTA's yearly costs. This greatly limits money for other needed projects.

In April 2012, the MBTA Advisory Board approved big fare increases for all MBTA services. They also approved cutting or ending some transit routes. In July 2014, fares went up again by about 5%.

Major Incidents

On May 28, 2008, a Green Line train crashed into a stopped train between the Waban and Woodland stations. At least seven people were hurt, and the driver of the moving train was killed. On May 8, 2009, two Green Line trains crashed between Park Street and Government Center. The driver of one train was text messaging. A rule banning cell phones for drivers was put in place days later.

After the Boston Marathon bombing, the MBTA was partly shut down. National Guardsmen were sent to various stations. During the search for the suspects, the MBTA was fully shut down. MBTA buses were used to move police around the city. After the suspect was caught, the MBTA went back to normal service. The next day, MBTA buses and subway cars displayed "BOSTON STRONG" and "WE ARE ONE BOSTON."

Charlie Baker's Time as Governor (2015–2023)

Crisis and Control Board

In February 2015, Boston had record-breaking snowfall. This caused a partial shutdown and big delays on all MBTA subway lines. Many long-term problems with the MBTA system became very clear to the public. Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker said he would talk about the money problems later.

After people criticized how he handled the emergency, Governor Baker formed a special group. This group was to figure out the MBTA's problems and suggest solutions. The group released its report in April. The report said the MBTA was in "severe financial distress" and was "governed ineffectively." It also said the MBTA spent money poorly and had many employees absent from work.

The report suggested several changes. These included temporarily stopping the MassDOT Board from running the MBTA. Instead, a temporary Fiscal and Management Control Board, chosen by the Governor and state leaders, would take over. The MassDOT Board resigned the next week. A law that followed these suggestions was passed in July. Governor Baker also appointed a new MassDOT Board and suggested a five-year plan to prepare for winter storms.

Safety Concerns

There were several serious incidents that got a lot of public attention. These included a Green Line crash, an escalator problem, a death where someone was dragged by a Red Line train, a fatal commuter train crash with a car, and a death from falling through a rusty staircase.

In April 2022, the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) announced it would take a bigger role in overseeing the MBTA's safety. They would do a safety inspection.

The FTA soon found that subway dispatchers were working 20-hour shifts because there weren't enough staff. The MBTA cut rush hour service on the Red, Blue, and Orange Lines to let dispatchers and supervisors rest. Federal inspectors also issued emergency orders about runaway trains in yards and a backlog of track maintenance. This caused about 10% of the subway system to have speed limits. After an Orange Line train caught fire, putting hundreds of passengers in danger, the MBTA decided to shut down the entire Orange Line for 30 days. This was to speed up track work and reopen with all new subway cars. In December 2022, the Orange Line could not even meet its reduced schedule. About half the trains were pulled from service without warning due to electrical problems.

The full FTA safety report in August 2022 demanded more staff and keeping experienced employees. It also asked for better ways to collect and use safety information, clearer safety rules for workers, and more resources for training. It also wanted the MBTA to fix radio dead zones and improve safety oversight.

Service Changes

In June 2015, the MBTA reduced a one-year trial program for late-night weekend service. This program was completely cut in March 2016. Despite this, some service improvements were made. In October 2015, the MBTA added nonstop trips during busy times on the Framingham/Worcester Line commuter rail. In March 2016, the MBTA reopened Government Center Station after two years of upgrades. In September 2016, the MBTA started a trial program with Uber and Lyft to improve paratransit services for disabled riders. This program was expanded in February 2017.

In December 2016, the MBTA board approved a plan to replace all MBTA Red Line trains by 2025. In January 2017, the MBTA announced that the new Boston Landing Station on the commuter rail would open in May. Work began in August on a $38.5 million renovation of Ruggles Station in Roxbury. In April 2017, the Federal Transit Administration approved a new cost estimate for the Green Line Extension. This allowed the project to get federal money. Construction for the Green Line Extension began in Somerville in June 2018.

In April 2018, the MBTA started a one-year trial for early morning bus service on some routes in Boston. This was made permanent in December. The MBTA Silver Line also started a route from Chelsea to South Station. In June 2018, the MBTA started a 3-month trial of a $10 weekend commuter rail fare for unlimited use. This was later extended and made permanent.

Budget and Fares

In August 2015, MBTA officials said the cost to fix the system was estimated to be $7.3 billion. While advertising money was up, a report showed that the MBTA's costs and debt payments were growing much faster than its income. The board voted to increase fares across the system by about 9.3% in March. However, in April 2016, it was estimated that the agency was losing $42 million per year because people were not paying fares. In June 2016, the MBTA board voted to continue a trial program of discounted passes for low-income young people and to increase the age limit to 25.

In July 2016, Governor Baker said there had been good progress. The MBTA's operating costs had leveled off, and operator absences and overtime costs had gone down. However, Baker also said the MBTA was "still in very tough shape." He mentioned concerns about the MBTA pension system, cash handling, and the need to improve how the MBTA buys things and maintains its infrastructure. Also in July 2016, Baker signed a law that limited MBTA fare increases to 7% every two years.

In October 2016, the MBTA board voted to hire a security company, Brink's, to handle the MBTA's cash for $18.7 million over five years. This decision was opposed by unions and elected officials. The MBTA also extended its contract with the Boston Carmen's Union through 2021. This new agreement would save the MBTA $80 million over four years. The next month, the agency hired an outside company to manage its warehouses and parts delivery for $28.4 million over five years.

In April 2017, the MBTA board approved a $1.98 billion budget. This reduced the MBTA's operating budget deficit. In May, Governor Baker approved the board's request to continue its control of the MBTA for two more years. In July 2017, interim MBTA General Manager Steve Poftak said the MBTA would spend more on capital projects. He also noted that the MBTA was "saving money" by hiring outside companies for some operations.

In November 2017, the MBTA board voted to give a 13-year contract worth $723 million to the Cubic Corporation. This company would design and run a new fare collection system for the MBTA by 2020. In February 2018, MBTA General Manager Luis Ramirez said the MBTA would have a $111 million operating budget deficit for the 2019 fiscal year. However, in August, MBTA officials announced that the agency had a balanced operating budget for the first time in 10 years.

COVID-19 Pandemic

In February 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic began to affect Massachusetts. When people were told to stay home, businesses closed, and people were advised to avoid public transit unless necessary. At its lowest point, MBTA ridership dropped significantly. Buses and subways ran on a modified Saturday schedule. Commuter trains ran less often, and ferries were completely shut down. To help with social distancing, buses started running without fares, and passengers had to enter through the rear door. Passengers also had to wear face masks. The MBTA began cleaning vehicles and stations often. Some employees got sick, which limited the number of drivers available. The MBTA received $827 million in federal aid to cover increased costs and lost income.

In June, the MBTA announced that commuter train tickets and passes from March 10 would be valid for 90 days starting June 22. They also made some fare changes to encourage riders to use less crowded options. This included discounted 10-ride tickets and half-price tickets for young people.

2021 Budget Proposal

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of people riding the MBTA dropped by 87%. This led Massachusetts lawmakers and the MBTA to consider a plan to cut services. This plan could eliminate weekend commuter train services and stop them after 9 p.m. on weeknights. It could also eliminate 25 bus routes and stop subway and bus services at midnight. If this plan was approved, it could save Massachusetts over $130 million.

Supporters of this plan believed it was the best option because most ridership had decreased due to the pandemic. They argued it was not practical to keep providing services that were not being used, especially if people had other ways to travel, like personal cars. By saving money from cutting services, the city planned to use that money for services once the pandemic ended. Supporters claimed that reduced services would still be enough for those who relied on public transport during the pandemic.

However, opponents argued that reducing services would make it harder for riders, especially low-income people or people of color, to get to essential jobs. Riders would be forced to find other ways to travel, which could mean using personal cars. Opponents believed public transportation should be treated as a public good. This means asking wealthier people and companies to pay their fair share to keep transportation running.

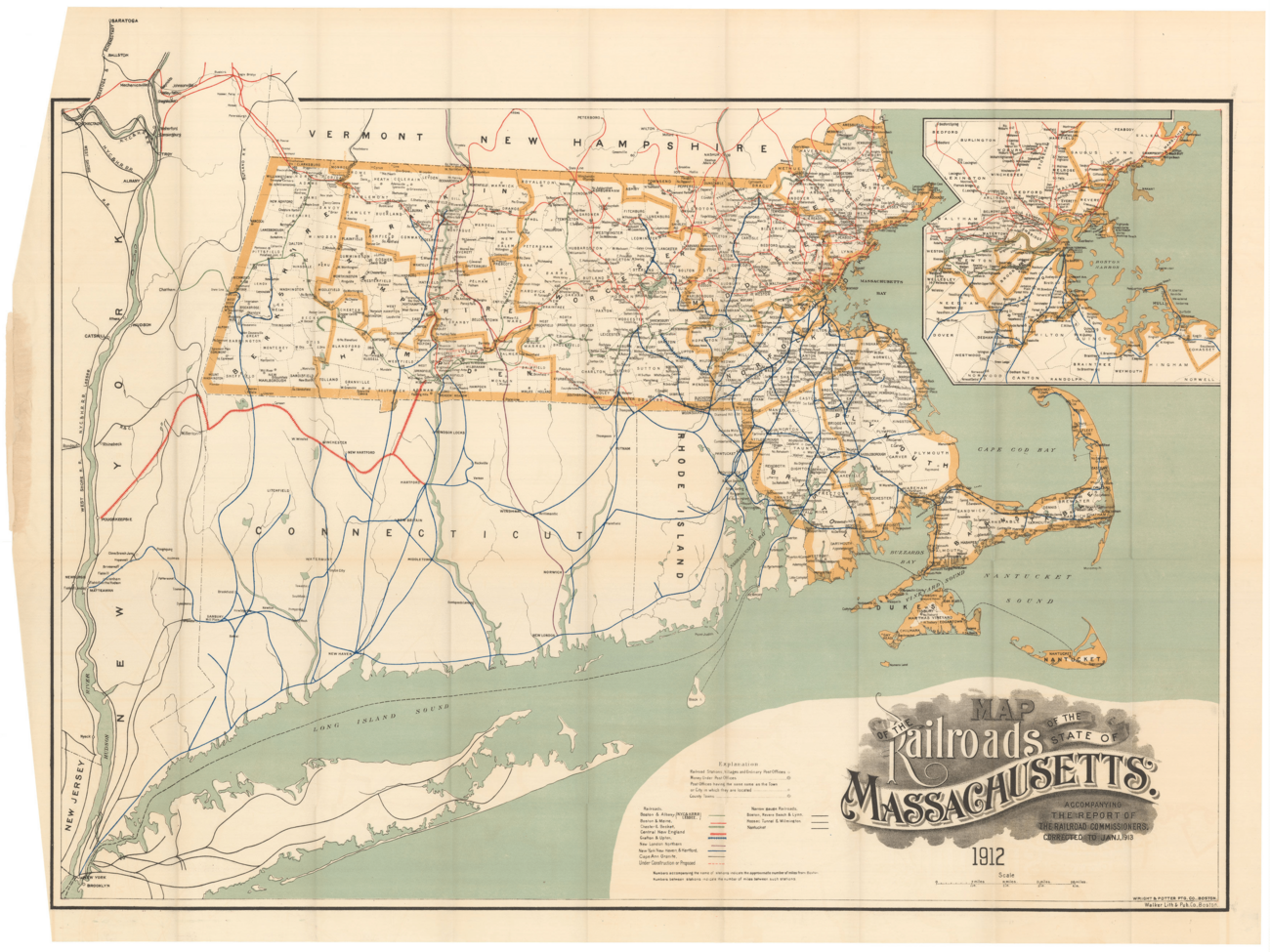

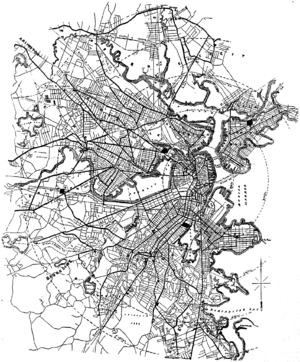

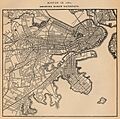

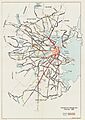

Maps gallery

See also

- Atlantic Avenue Elevated

- Boston Elevated Railway

- Boston Street Railway Association

- Causeway Street Elevated

- Charlestown Elevated

- Green Line (MBTA)

- Lechmere Viaduct

- MBTA kickback schemes

- Trolleybuses in Greater Boston

- Washington Street Elevated

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |