History of union busting in the United States facts for kids

The history of union busting in the United States goes back to the 1800s, during the Industrial Revolution. This was a time when many factories and industries grew quickly. As people moved from farms to work in factories and mines, they often faced tough conditions. These included long hours, low pay, and dangerous workplaces. Children and women also worked in factories, usually for less money than men. The government at first did little to help with these problems.

Because of these issues, groups of workers called labor unions or trade unions started forming. They wanted better rights and safer conditions for workers. Over time, the relationship between unions and company owners was often difficult and sometimes violent. Today, "union busting" describes actions taken by employers to stop workers from forming or joining unions, or to weaken existing ones. This can happen during protests, when workers try to organize, or during strikes. Laws about labor have changed how union busting happens and how unions try to organize.

Contents

Early Union Busting: 1870s–1935

Since the late 1800s, companies have hired special agencies to help them stop unions. These agencies have been around through many tough strikes.

In 1874, Charles Pratt's Astral Oil Works bought other oil companies to reduce competition. The barrel makers' union, called coopers, didn't like Pratt's plans to cut back on manual work. Pratt then worked to break up their union. Other companies later copied his methods.

Companies used many creative ways to stop unions. In 1907, a detective from the Pinkerton National Detective Agency joined the Western Federation of Miners secretly. He took control of their strike fund and tried to spend all their money by giving out too many benefits to strikers. Many times, however, companies used force, like police, military, or hired toughs, against unions.

Physical Attacks Against Unions

Some unions, like the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), were badly hurt by government actions. For example, the Palmer Raids were part of the "First Red Scare," a time when the government was worried about communism. The Everett Massacre in 1916 was a violent fight between local police and IWW members in Washington state. Later, during the "Second Red Scare," unions thought to be led by communists were weakened or destroyed.

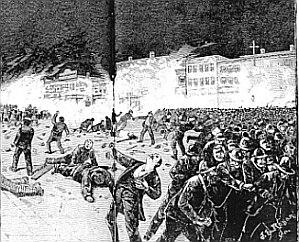

In May 1886, the Knights of Labor union held a protest in Haymarket Square in Chicago. They were asking for an eight-hour day for all workers.

Other strikes happened that same month in places like Milwaukee. There, seven people died when the governor ordered state soldiers to shoot at thousands of striking workers. These workers had marched to a factory in Bay View, Wisconsin.

In 1914, a very difficult labor conflict happened at a mining town in Colorado called Ludlow. Workers went on strike in September 1913, asking for an eight-hour day and complaining about unfair treatment. The governor called in the Colorado National Guard. That winter, the soldiers arrested 172 people.

The strikers fought back, killing four mine guards. The National Guard's General Chase then ordered the destruction of the workers' tent camp. Twenty-six people were killed in this event.

Union Busting with Police and Military

For about 150 years, efforts to organize unions and strikes were often met with force. Police, private security, the National Guard, and even the United States Army were used. Important events include the Haymarket Riot and the Ludlow massacre. The Homestead strike of 1892, the Pullman strike of 1894, and the Colorado Labor Wars of 1903 are examples where military force greatly damaged or destroyed unions. In all these cases, a strike led to the use of force.

- Pinkertons and Soldiers at Homestead, 1892 - The Pinkerton National Detective Agency was one of the first agencies hired to break unions. They became well-known after a shooting battle between strikers and 300 Pinkerton agents during the Homestead Strike in 1892. When the Pinkertons left, state soldiers were sent in. The soldiers stopped attacks on the Carnegie Steel Company plant. They also protected workers who crossed the picket lines to replace strikers. This led to the union's defeat at Homestead.

- Federal Troops End Railroad Blockades, 1894 - During the Pullman Strike, the American Railway Union (ARU) called its members to stop trains. Their actions were illegal but worked well until 20,000 federal troops were called in. The troops made sure trains carrying U.S. mail could move freely. Once the trains ran, the strike ended.

- National Guard in the Colorado Labor Wars, 1903 - The Colorado National Guard, a group of employers called the Citizens' Alliance, and the Mine Owners' Association worked together. They forced the Western Federation of Miners out of mining camps across Colorado.

Stopping Strikes with Court Orders

In May 1895, the Supreme Court said the government could use court orders, called injunctions, to end labor strikes.

This came from a court order against Eugene V. Debs, the head of the American Railway Union, during the Pullman Strike of 1894. President Grover Cleveland supported the Pullman Company. His attorney general asked a judge to issue a court order to stop the strike. The judge issued a very broad order that stopped Debs and other union leaders from interfering with railroads. In July 1894, Debs and four other union leaders were arrested for breaking this order. They were sentenced to prison for three to six months.

Using court orders to stop strikes continued until the Norris–La Guardia Act was passed in 1932. This law stopped federal courts from issuing injunctions against peaceful labor actions like strikes and picketing.

How a Union Buster Worked

The Corporations Auxiliary Company, a union-busting firm in the early 1900s, explained their methods to employers. They would send a secret agent into a factory to get to know the workers. If workers didn't seem interested in forming a union, the agent would try to keep it that way. If workers wanted to organize, the agent would become a leader and pick certain people to join. Once a union formed, their agent would try to stop it from growing. They might suggest meetings be held far apart or arrange a weak contract with the employer.

If these tactics didn't work and a strong union formed, the agent would become very extreme. They would ask for unreasonable things and cause problems for the union. If a strike happened, the agent would be the loudest voice, encouraging violence. This would get people into trouble and break up the union.

Between 1933 and 1936, this company worked for 499 different businesses.

College Students as Strikebreakers

In 1905, during a subway strike in New York City, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company asked university students to volunteer. These students worked as train drivers, conductors, and ticket sellers. Historians note that college students often volunteered to be strikebreakers in the early 1900s. They were less likely to be swayed by the pleas of striking workers.

Early "Kings of Strikebreakers"

Many strikes happened in the 1890s and early 1900s. Hiring large numbers of replacement workers became a big business.

Jack Whitehead saw a chance to make money from labor disputes. He left his union and started an army of strikebreakers. He was called the first "King of the Strike Breakers." He became rich by sending his private workforce to break steelworker strikes in Pittsburgh and Birmingham. Whitehead showed how profitable strikebreaking could be, inspiring others to do the same.

James Farley Takes Over the Title

After Whitehead, men like James A. Farley and Pearl Bergoff turned union busting into a huge industry. Farley started his strikebreaking career in 1895. In 1902, he opened a detective agency in New York City. Besides detective work, Farley specialized in breaking streetcar driver strikes. He hired tough, brave men and sometimes they openly carried guns. They were paid more than the striking workers. Farley was known for successfully breaking many strikes, sometimes using hundreds or thousands of strikebreakers. He was paid as much as $300,000 for breaking a strike and by 1914, he had earned over $10 million. Farley claimed he had won 35 strikes in a row.

Bergoff Brothers Strike Service

Pearl Bergoff also started his strikebreaking career in New York City. He worked as a "spotter" on the Metropolitan Street Railway, watching conductors to make sure they recorded all fares. In 1905, Bergoff started the Vigilant Detective Agency. Within two years, his brothers joined, and the name changed to Bergoff Brothers Strike Service and Labor Adjusters. Bergoff's early actions were very violent. A 1907 strike by garbage cart drivers led to many fights between strikers and strikebreakers.

In 1909, the Pressed Steel Car Company in Pennsylvania fired 40 men, and 8,000 employees walked out. Bergoff's agency hired toughs and sent ships full of immigrant workers directly into the strike area. Other immigrant strikebreakers were brought in boxcars and not fed for two days. They later worked, ate, and slept in a barn with 2,000 other men, eating only cabbage and bread.

There were violent clashes between strikers and strikebreakers. There were also fights between strikebreakers and guards when the scared workers demanded to leave. An immigrant who escaped told his government that workers were being held against their will, causing an international problem. Besides kidnapping, strikebreakers complained about lies, broken promises about pay, and bad food.

During government hearings, Bergoff said his "musclemen" would "get... any graft that goes on." This meant they would take money unfairly. Other reports said Bergoff's main assistant, a very large man, had 35 guards who scared and robbed the strikebreakers. They even locked them in a boxcar prison without bathrooms when they didn't follow orders.

At the end of August, a gunfight broke out, leaving six dead, six dying, and 50 wounded. Public sympathy started to shift from the company to the strikers. In early September, the company gave up and talked with the strikers. Twenty-two people died in the strike. But Bergoff's business wasn't hurt. He claimed to have 10,000 strikebreakers on his payroll and was getting paid up to $2 million for each job.

Spies and Saboteurs

Hiring many tough strikebreakers became less popular in the 1920s because there were fewer strikes. By the 1930s, agencies started using more secret informants and labor spies.

Spy agencies hired to break unions became very clever. "Missionaries" were secret agents trained to spread rumors to cause arguments on picket lines and in union halls. They didn't just target strikers. For example, female agents might visit strikers' wives at home, telling sad stories about how strikes ruined their own families. These campaigns could destroy not only strikes but also unions themselves.

In the 1930s, the Pinkerton Agency had 1,200 labor spies. Nearly one-third of them held high positions in the unions they were spying on. The International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers was hurt when a Pinkerton agent, Sam Brady, held a high enough position to cause a strike too early. In a United Auto Workers local union in Michigan, Pinkerton agents forced out all but five officers. The five who stayed were Pinkertons. At another company, the union was so damaged by secret agents that its membership dropped from over 2,500 to fewer than 75.

Union Busting: 1936–1947

In 1937, during the Little Steel strike, about 8,000 striking steelworkers were illegally fired. More than 1,000 strikers were arrested. Between 16 and 18 strikers were killed, including 10 workers in the 1937 Memorial Day massacre.

Since a 1937 Supreme Court decision, companies in the U.S. have had the legal right to permanently replace workers who go on economic strikes (strikes about pay or working conditions).

Around this time, employers wanted more subtle ways to stop unions. This led to a new field called "preventive labor relations." People in this field had degrees in psychology, management, and law. They used their skills to work around labor laws and influence workers' feelings about unions.

Nathan Shefferman and Labor Relations Associates

After the Wagner Act was passed in 1935, the first well-known union-busting agency was Labor Relations Associates (LRA). Nathan Shefferman founded it in 1939. He later wrote a guide to modern union busting and is seen as the "founding father" of the union avoidance industry. Shefferman had been part of the original National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).

By the late 1940s, LRA had nearly 400 clients. Shefferman's agents set up anti-union groups of employees called "Vote No" committees. They found ways to identify pro-union workers and helped arrange weak contracts with unions that wouldn't challenge management. Consultants from LRA "committed many illegal actions, including bribery, forcing employees to do things, and illegal business practices."

Shefferman built a big business on false ideas. One of the most unbelievable, but widely believed, was the idea that companies were at a disadvantage compared to unions. What businesses wanted was for Congress to change the Wagner Act.

One of Shefferman's partners explained his method simply: "We work exactly like a union does," he said. "But for the management side. We hand out flyers, talk to employees, and organize a propaganda campaign."

Union Busting: 1948–1959

In 1956, Nathan Shefferman stopped a union effort at seven stores in Boston. He used tactics that a company vice-president called "unnecessary and disgraceful." At a factory in Ohio, an LRA agent created a system to track employees' feelings about unions. Many workers he thought were pro-union were fired. A similar thing happened at a food plant in Iowa. An employee hired by LRA agents made a list of workers who seemed to favor a union. Management fired those workers. The list-making employee got a big pay raise. When the union was defeated, Shefferman arranged a weak contract with a union that the company controlled, without the workers' input. From 1949 to 1956, LRA made almost $2.5 million from these anti-union services.

In 1957, a U.S. Senate committee investigated unions for corruption and employers for union-busting. Labor Relations Associates was found to have broken the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. This included rigging union elections with bribes, threatening workers, putting pro-management officers in unions, rewarding anti-union employees, and spying on workers. The committee felt that the National Labor Relations Board was "powerless" to stop Shefferman's activities.

Union Busting: 1960-2000

There isn't much proof that companies used anti-union services in the 1960s or early 1970s. However, by the late 1970s, consulting agencies stopped filing required reports.

The 1970s and 1980s were a tougher time for unions. A new, multi-billion dollar union-busting industry grew, using experts in psychology, law, and strike management. These experts were good at getting around the rules of labor laws. In the 1970s, the number of consultants and their clever tactics increased a lot. As more consultants were used, unions lost more elections. The percentage of union wins in elections dropped from 57% to 46%. The number of times workers voted to remove their union tripled, with unions losing 73% of these votes.

Labor relations firms started giving seminars on how to avoid unions in the 1970s. Agencies shifted from secretly hurting unions to screening out union supporters when hiring. They also taught workers anti-union ideas and spread propaganda against unions.

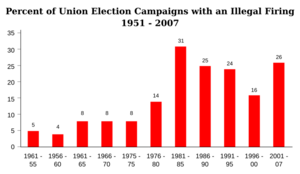

In August 1981, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) went on strike for better pay and conditions. When the striking workers refused a court order to return to work, President Ronald Reagan ordered the government to fire all 11,345 strikers. He then hired new workers to replace them. Most of the striking workers were permanently banned from federal jobs. In October 1981, PATCO was officially removed as a union. This event led to a decade of lost strikes and company demands for workers to give back pay and benefits.

By the mid-1980s, Congress had looked into, but failed to control, the unfair actions of labor relations firms. Some companies continued to use persuasion and manipulation. Others launched very aggressive anti-union campaigns. At the start of the 21st century, union-busting methods were similar to those used at the start of the 20th century. The government's labor board and department of labor often failed to enforce labor laws against companies that broke them.

From 1960 to 2000, the percentage of workers in the U.S. who belonged to a union fell from 30% to 13%. This was mostly in private companies. This happened even though more workers wanted to join unions since the early 1980s. A book called Winner-Take-All Politics suggests that changes in Washington D.C. from the late 1970s weakened the main labor law. Stronger business lobbying meant "few real limits on ... strong antiunion activities." Reports of law breaking by companies went way up in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Meanwhile, strikes dropped sharply. Many strikes that did happen were acts of desperation, not signs of union strength.

In Canada, where the economy and worker feelings about unions are similar, union membership was more stable. From 1970 to 2003, union membership in the U.S. dropped from 23.5% to 12.4%. In Canada, the drop was much smaller, from 31.6% to 28.4%. One reason for this difference is that Canadian law allows easier union recognition and rules against permanently replacing striking workers. It also limits company propaganda.

Union Busting: After 2000

Legal Union-Avoidance Tactics

Companies use common legal tactics to stop unions. These include making employees attend "captive audience meetings" where only anti-union views are shared. They also cover the workplace with anti-union posters or videos. Managers might tell workers they could lose their jobs if they vote for a union. Managers also hold one-on-one meetings to argue against unions. Companies often say that unions will make the business fail, that unions only care about collecting dues, or that unions are not needed. Overall, U.S. employers spend about $340 million each year on consultants to help them stop employees from forming unions.

Anti-Union Company Training

Many U.S. companies have also created anti-union training materials for their managers.

In 2018, Amazon gave a 45-minute anti-union training video to managers at Whole Foods, which Amazon owned. The video told managers to look for signs that workers might be organizing. These signs included using the term "living wage" or showing "unusual interest in policies, benefits, or employee lists." Managers were told to report any potential organizing immediately.

In January 2022, Target sent new training documents to store managers. These documents told managers to look for signs of union organizing, such as workers talking about pay, benefits, or job security. Managers were told to work with human resources to prevent unions.

Anti-Union Laws

In May 2024, the governor of Alabama signed a new law. This law stops companies in the state from getting government money or tax breaks if they willingly recognize a workers' union. Instead, the law requires workers to vote on whether to unionize.

History of Labor Laws

Railway Labor Act, 1926

The Railway Labor Act (RLA) of 1926 was the first major labor law passed by Congress. It was changed in 1936 to also cover the airline industry. This law was created because railroad companies wanted to keep trains moving and stop sudden strikes. Railroad workers wanted to make sure they could organize, be recognized by companies, and negotiate agreements. Under the RLA, agreements don't have end dates but have "amendable dates" when they can be changed.

Wagner Act, 1935

The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), also known as the Wagner Act, was passed on July 5, 1935. It gave workers the right to form unions. This was a very important labor law, sometimes called "labor's bill of rights." It stopped employers from five unfair labor practices:

- Stopping employees from organizing or bargaining.

- Trying to control a union.

- Refusing to bargain fairly with unions.

- Encouraging or discouraging union membership through special job conditions or by treating union or non-union members differently when hiring.

Before this law, employers could spy on, question, punish, blacklist, and fire union members. In the 1930s, many workers started to organize. There were many strikes in 1933 and 1934, including city-wide strikes and workers taking over factories. There were often fights between workers trying to organize and police or hired security who supported factory owners. Some historians believe Congress passed the NLRA to prevent even more serious worker unrest. The Wagner Act required employers to recognize unions that most of their workers wanted. It also created the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to oversee union elections and unfair practices by employers.

Taft–Hartley Act, 1947

The Taft–Hartley Act greatly changed the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. It was the first big change to a "New Deal" law passed after World War II. In 1946, the Republican Party gained control of Congress. The bill passed both houses with strong support from both parties.

Union officials strongly criticized the Taft–Hartley Act, calling it a "slave labor" bill. President Truman vetoed the bill, but Congress overrode his veto on June 23, 1947. Many Democrats in Congress also voted to override the veto. However, 28 Democratic members of Congress called it a "new guarantee of industrial slavery."

Management always had the upper hand, of course; they had never lost it. But thanks to Taft–Hartley, the bosses could once again wage their war with near impunity.

Taft–Hartley gave the National Labor Relations Board the power to act against unions that engaged in unfair labor practices. Before, the board could only look at unfair practices by employers. It also defined specific rights for employers, giving them more options during union organizing drives. It banned "closed shops," where union membership was required to work at a unionized workplace. It also allowed states to pass "right to work" laws, which stop mandatory union dues.

The act required union officials to swear they were not communists. The Supreme Court overturned this rule in 1965.

The act also gave the president the power to ask courts to end a strike if it caused a national emergency. Presidents have used this power 35 times to stop strikes. Most of these happened in the late 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. The last two times were in 1978 and 2002.

Landrum–Griffin Act, 1959

The Landrum–Griffin Act of 1959, also known as the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA), set rules for how unions and management groups must report their finances. Under this law, employers must report the costs of any activities by consultants meant to persuade workers about unions.

According to Martin J. Levitt, a former union buster, the law regulates how unions operate internally and how union officials interact with employers. However, he noted that "loopholes" in the law allow management and their agents to ignore rules meant to control their behavior. Consultants often use supervisors and managers to talk to employees, which helps them avoid reporting requirements. Even before the Act, labor consultants knew that front-line supervisors were the best people to lobby for management.

Landrum–Griffin also tries to stop consultants from spying on employees or unions. Information is only supposed to be collected for specific legal cases. But Levitt said it's easy for consultants to use this rule as an excuse for "all kinds of information gathering."

Levitt also stated that because the law's language is unclear, lawyers can directly interfere in union organizing without having to report it. So, "young lawyers run bold anti-union wars and dance all over Landrum–Griffin." The law's special rights for lawyers allowed labor consultants to work under the protection of lawyers, making it easy to get around the law's purpose.

Levitt said:

With the help of our trusted attorneys, our anti-union activities were carried out [under Landrum-Griffin] in backstage secrecy; meanwhile we gleefully showcased every detail of union finances that could be twisted into implications of impropriety or incompetence.

Images for kids

-

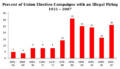

Anti-union cartoon in monthly magazine The American Employer depicting the AFL as a fly on the wheel, 1913

-

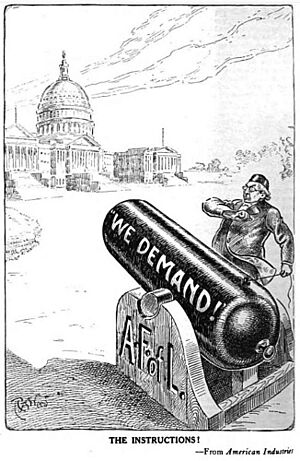

Anti-union cartoon in monthly magazine The American Employer depicting the AFL as a cannon aimed at a government building, 1914

-

Illegal union firing increased during the Reagan administration and has continued since.

See also

- Union busting

- Grabow Riot

- Labor spies

- Mohawk Valley formula

- Strike breaking

- Trade union

- Union Organizer

- Union threat model

- Union wage premium

- Salt (union organizing)

- Martin J. Levitt