Holy Child of La Guardia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Holy Child of La Guardia |

|

|---|---|

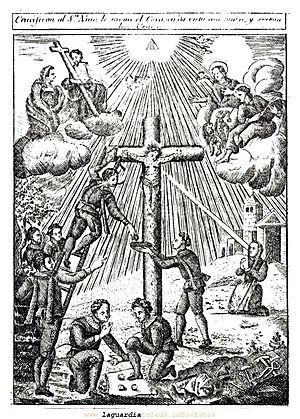

An engraving with the martyrdom of the Holy Child of La Guardia

|

|

| Died | Good Friday, 1491 |

| Venerated in | Folk Catholicism |

| Major shrine | Monastery of St. Thomas of Avila, La Guardia, Spain |

| Controversy | blood libel |

The Holy Child of La Guardia (Spanish: El Santo Niño de La Guardia) is a folk saint in Spanish Roman Catholicism. This story is linked to a false accusation from the Middle Ages called a blood libel. This event happened in the town of La Guardia in central Spain.

On November 16, 1491, a public event called an auto-da-fé took place near Ávila. Several Jewish people and conversos (people who had converted from Judaism to Christianity) were publicly executed. These individuals had confessed to harming a child after being questioned. However, no body was ever found. There is no proof that a child disappeared or was killed. The confessions were confusing, making it hard for the court to understand what supposedly happened. Many people also question if the child even existed.

Like Pedro de Arbués, the Holy Child quickly became a saint through popular belief. His story helped the Spanish Inquisition and its leader, Tomás de Torquemada. They used it in their efforts against heresy (beliefs different from official church teachings) and crypto-Judaism (secretly practicing Judaism). The belief in the Holy Child is still celebrated in La Guardia today.

The Holy Child case is known as Spain's "most infamous case of blood libel." This event happened one year before the expulsion of the Jews from Spain. Some believe the story was used as a reason to expel Jewish people from Spain.

In 2015, the official website of the Archdiocese of Madrid published an article. It described the Holy Child as a "martyr" and stated that the events truly happened. This article remains online as of 2023.

Contents

Understanding Blood Libel in Spain

During the Middle Ages, false accusations called blood libels were often made against Jewish people in Spain. These accusations claimed that Jewish people used Christian blood for religious rituals. The "Seven Part Code of Castile" from the 13th century, a set of laws, even mentioned this popular belief:

We have heard that in some places, Jewish people celebrated Good Friday, which remembers Jesus Christ's suffering, by disrespecting it. They supposedly stole children and tied them to crosses. If they could not get children, they made wax figures and crucified them. We order that if anything like this happens in our lands and can be proven, all people involved will be arrested and brought before the king. If the king finds them guilty, they will be put to death in a shameful way, no matter how many there are. (Alfonso X the Wise, Partidas, VII, XXIV, Law 2)

Many people in Spain believed several such events had occurred. One famous example was the supposed crucifixion of Little Saint Domingo of Val in Zaragoza in the 13th century. Another was the Boy of Sepúlveda in 1468. This last event led to the execution of sixteen Jewish people found guilty. It also caused a mob attack on the Jewish community in Sepúlveda, where more lives were lost.

Today, there is no proof that any of these murders or related crimes actually happened. These accusations and the punishments that followed are now seen as examples of anti-Semitism, which is hatred or prejudice against Jewish people.

The Accusation and Trial Process

The story of the Holy Child was known through legends and trial documents until 1887. In that year, Spanish historian Fidel Fita found and published details from the trial of Yucef Franco. This was one of the accused individuals. His account, published in the Boletin de la Real Academia de la Historia, is one of the most complete records of a Spanish Inquisition trial that still exists.

The Arrest of Benito García

In June 1490, a traveling cloth carder named Benito García was stopped in Astorga. He was 60 years old and from La Guardia. A consecrated Host (a blessed wafer used in Christian communion) was found in his bag. He was taken for questioning by Pedro de Villada, a judge for the Bishopric of Astorga. Benito García's confession, dated June 6, 1490, shows he was first accused only of secretly practicing Judaism. He explained that five years earlier (1485), he had secretly returned to the Jewish faith. He said he was encouraged by another converso, Juan de Ocaña, also from La Guardia, and a Jewish man named Franco from Tembleque.

The Arrest of Yucef Franco

A Jewish cobbler named Yucef Franco, 20 years old, from Tembleque, was mentioned by Benito García. The Inquisition arrested Yucef Franco on July 1, 1490, along with his 80-year-old father, Ça Franco. Yucef was in prison in Segovia by July 19, 1490, when he became ill. A doctor, Antonio de Ávila, visited him. Yucef asked the doctor if he could see a Rabbi. Instead of a Rabbi, the doctor brought a converso Friar, Alonso Enriquez, who was disguised as a Rabbi and called himself Abrahán. When asked why he thought he was arrested, Yucef said he was accused of ritually murdering a Christian boy. The second time the two men visited him, Yucef did not mention this accusation again.

The Indictment and Inquisitors

Yucef's later statements involved other Jewish people and conversos. On August 27, 1490, the Grand Inquisitor Tomás de Torquemada ordered the prisoners moved from Segovia to Ávila for trial. The order listed all prisoners related to this case held in Segovia. They included conversos: Alonso Franco, Franco Lope, García Franco, Juan Franco, Juan de Ocaña, and García Benito, all from La Guardia. The Jewish prisoners were Yucef Franco of Tembleque and Moses Abenamías of Zamora. The charges included heresy, apostasy (abandoning one's religious faith), and crimes against the Catholic faith. Interestingly, the order did not mention Ça Franco.

The inquisitors preparing the trial were Pedro de Villado (who had questioned Benito García earlier), Juan López de Cigales, and Friar Fenando de Santo Domingo. All of them were trusted by Torquemada. Santo Domingo had also written the introduction to a published anti-Jewish pamphlet.

The Trial and Confessions

The trial against Yucef Franco began on December 17, 1490, and lasted several months. He was accused of trying to bring conversos back to Judaism. He was also accused of taking part in the ritual crucifixion of a Christian child on Good Friday. It seems that before the trial, Benito García and Yucef Franco had already partly confessed. They had given evidence against others, hoping to gain their freedom. However, this was a trick by the Inquisition.

When the charges were read, Yucef Franco shouted that they were completely false. He was given a lawyer for his defense. The lawyer argued that the charges were too vague, no dates were given, there was no body, and the victim was not even named. He also argued that as a Jewish person, Yucef could not be guilty of heresy or apostasy. The defense asked for Yucef to be found not guilty. The court rejected this request, and the trial continued.

The confessions of Yucef, obtained under questioning, at first only mentioned talks with Benito García in jail. They only accused them of secretly practicing Judaism. But later, the confessions started to mention a witchcraft act from about four years earlier (perhaps 1487). This act supposedly involved a consecrated Host, stolen from a church in La Guardia, and the heart of a Christian boy. Yucef's later statements gave more details and especially accused Benito García. García's statements were also kept, and taken "while he had been put to the torture." These statements did not match Yucef's, and mainly accused Yucef. The inquisitors even arranged a meeting between the two accused on October 12, 1491. The court records say their statements matched, which is surprising since they had contradicted each other before.

In October 1491, one of the inquisitors, Friar Fernando de San Esteban, went to Salamanca. He consulted with legal and religious experts. They declared the accused guilty. In the final part of the trial, the evidence was made public. Yucef tried to prove it wrong but was unsuccessful. Yucef's last statements, obtained under questioning in November, added more details to the story. Many of these details clearly came from anti-Jewish writings.

Execution and Aftermath

On November 16, 1491, in Ávila, all the accused were handed over to the government authorities. They were burned at the stake. Nine people were executed: three Jewish individuals (Yusef Franco, Ça Franco, and Moses Abenamías) and six conversos (Alonso, Lope, García, and Juan Franco, Juan de Ocaña, and Benito García). As was common, the sentences were read aloud at the auto-da-fé. The sentences for Yucef Franco and Benito García have been preserved.

The money and goods taken from the prisoners were used to help build the monastery of Santo Tomás de Ávila. This monastery was finished on August 3, 1493.

The Legend of the Holy Child

During the 1500s, a legend grew that the death of the Holy Child was similar to that of Jesus Christ. It even highlighted similarities between the town of La Guardia and Jerusalem, where Jesus died.

In 1569, Sancho Busto de Villegas, a member of the Supreme Council of the Inquisition, wrote an "Authorized Account of the Martyrdom of Saint Innocent." He based it on the trial documents. In 1583, Friar Rodrigo de Yepes published "The History of the Death and Glorious Martyrdom of the Holy Innocent said to be from La Guardia." Other stories about the Holy Child appeared later, helping to build the legend.

The legend, built from these stories, says that some conversos planned revenge on the inquisitors. They wanted to use magic. For their spell, they needed a consecrated Host and the heart of an innocent child. Alonso Franco and Juan Franco supposedly kidnapped a boy near Toledo Cathedral and took him to La Guardia. There, on Good Friday, they held a fake trial. The boy, sometimes called Juan and sometimes Cristóbal in the legend, was said to be the son of Alonso de Pasamonte and Juana la Guindero. (However, no body was ever found.) Local Christians believed he was whipped, crowned with thorns, and crucified at the fake trial, just like Jesus Christ. His heart, needed for the spell, was supposedly removed. At the exact moment the child died, his mother, who was blind, miraculously regained her sight.

After burying the body, the supposed murderers stole a consecrated Host. Benito García set off for Zamora, carrying the Host and the heart for his spell. But he was stopped in Ávila (far from Astorga, where he was first arrested). He was caught because of a bright light coming from the consecrated Host he had hidden in a prayer-book. His confession supposedly led to the discovery of the other people involved. After the Holy Child's death, several miraculous healings were said to have happened because of him.

The consecrated Host is kept in the Dominican monastery of St. Thomas in Ávila. The heart was said to have disappeared miraculously, like the child's body. Legends grew that, like Jesus Christ, he had been brought back to life.

The Holy Child in Art and Stories

Yepes mentioned a lost altarpiece (a painting behind an altar) in the Holy Child's chapel in La Guardia. It was ordered by Alonso de Fonseca, archbishop of Toledo. This altarpiece showed scenes of the child's kidnapping, trial, whipping, and crucifixion. It also showed the capture and execution of his supposed murderers. The main part of this altarpiece showed the crucifixion and the removal of the child's heart.

In the National History Archives in Madrid, there is a painting from the second half of the 1500s showing the same scene. This painting suggests that the belief in the Holy Child of La Guardia is very old.

There is also a mural in Toledo Cathedral, believed to be by Bayeu, showing the crucifixion of the Holy Child of La Guardia. It can be seen near the "del Mollete" door. Sadly, moisture and weather inside the cathedral cloister have caused the painting to decay.

The play El niño inocente de La Guardia (The Innocent Child of La Guardia) by Lope de Vega was likely inspired by the legend. This play from the Golden Age of Spanish Literature is known for its harshness in the last act, showing the child's crucifixion. This scene was copied by José de Cañizares in his play La viva imagen de Cristo: El Santo Niño de la Villa de la Guardia (The Living Image of Christ: The Holy Child of Villa de la Guardia).

In one of Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer's legends, La Rosa de Pasión (The Rose of Passion), a Jewish woman named Sara argues with her father, Daniel, about his hatred of Christians. She dies in a ritual very similar to the Santo Niño de la Guardia. When she sees the preparations, she even thinks about the story of the Holy Child.

Impact of the Legend

The story of the Holy Child had immediate and major effects on both the Jewish community in Spain and the Spanish nobility.

Expulsion of Jewish People

With Tomás de Torquemada's strong encouragement, Queen Isabella I used this story as one of the reasons for the expulsion of the Jews from Spain. This happened after the fall of Granada in 1492.

Purity of Blood Laws

Because of the fear that heresy could be passed down through families, the outcome of this trial, which involved conversos and Jewish people, was used to support the idea of "purity of blood" (limpieza de sangre). This meant that people who wanted to join the clergy (religious leaders) in the archdiocese of Toledo had to prove their family had no Jewish or Muslim ancestors. Many nobles could not prove their "pure" ancestry. Because of this, they were not allowed to hold important positions in the main church of Spain.

See also

In Spanish: Santo Niño de La Guardia para niños

In Spanish: Santo Niño de La Guardia para niños

- Dominguito del Val

- Gavriil of Belostok

- List of unsolved murders

- Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln

- Menahem Mendel Beilis

- Satanic ritual abuse

- Simon of Trent