History of the Jews in Spain facts for kids

The history of Jewish people in Spain goes back a very long time, some say even to Biblical times. However, organized Jewish communities likely started forming in Spain after the Second Temple was destroyed in 70 CE. The oldest proof of Jewish presence in Spain is a gravestone from the 2nd century found in Mérida. Things got much harder for Jews from the late 6th century onwards, after the Visigothic kings changed their religion from Arianism to Catholicism.

After the Muslim conquest in the early 8th century, Jews lived under a system called Dhimmi and gradually adopted Arab culture. Jewish people in Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) were especially important during the 10th and 11th centuries. This was a time when they started studying the Hebrew Bible scientifically and writing poetry in Hebrew for the first time. After the Almoravid and Almohad invasions, many Jews fled to Northern Africa and the Christian kingdoms in Spain.

During the 14th century, Jews in Christian kingdoms faced persecution and violent attacks, leading to the 1391 pogroms. Because of the Alhambra Decree in 1492, the remaining Jews in Castile and Aragon were forced to convert to Catholicism. Those who continued to practice Judaism (about 100,000–200,000 people) were expelled. This created new Jewish communities in Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia, known as Sephardi Jews. Since a 1924 law, there have been efforts to help Sephardi Jews return to Spain by making it easier for them to get Spanish citizenship if they can prove their ancestry.

Today, an estimated 13,000 to 50,000 Jews live in Spain.

Contents

- Early Jewish Presence in Spain

- Visigothic Rule: Hard Times for Jews (5th Century to 711 CE)

- Muslim Spain: A Golden Age (711 to 1492 CE)

- Jewish Life in Christian Kingdoms (974–1300 CE)

- Challenges and Massacres (1300–1391)

- From Persecution to Expulsion (1391–1492)

- The Expulsion of Jews from Spain

- Conversos: Secret Jews

- Modern Jewish Life (1858 to Today)

- See also

Early Jewish Presence in Spain

Some people think the country of Tarshish, mentioned in the Bible, might have been in southern Spain. The Bible describes Tarshish as a very far-west place you could sail to. It's possible that Jewish merchants or craftspeople came to Tarshish with the Phoenicians. While this is just a guess, it suggests Jews might have been in Spain very early on.

More solid proof of Jews in Spain comes from the Roman era. Even before the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE, Jews had already started moving from Israel to other parts of the Roman Empire. The Roman writer Valerius Maximus mentioned Jews being expelled from Rome in 139 BCE. The Jewish historian Josephus also wrote that Jews lived all over the Roman Empire.

The Spanish rabbi Abraham ibn Daud wrote in 1161 that the Jewish community in Granada believed they were from Jerusalem. He also wrote about his grandmother's family, who came to Spain after Titus conquered Jerusalem. They were among the nobles sent to Mérida.

The Bible book of Obadiah (1:20) mentions "Sepharad" as a place where exiles from Jerusalem would live. Many scholars believe "Sepharad" refers to Spain. Around 960 CE, Hisdai ibn Shaprut, a Jewish minister in Córdoba, wrote that the name of their land in Hebrew was "Sepharad."

Some scholars like David Kimhi (1160–1235) also believed that "Sepharad" meant Spain. Other Jewish traditions suggest that Jews lived in Spain even since the destruction of the First Temple. For example, Moshe ben Machir (16th century) wrote that some Jews refused to return to Jerusalem after the Babylonian captivity because they knew the Second Temple would also be destroyed. He said these were the people of Toledo.

Don Isaac Abrabanel, an important Jewish leader in Spain in the 15th century, wrote that the first Jews came to Spain by ship. He said they were brought by a Greek ally of the King of Babylon during the siege of Jerusalem. These Jews, from the tribes of Judah, Benjamin, Shimon, and Levi, settled in southern Spain, in areas like Andalusia and around Toledo. Abrabanel believed Toledo's name came from the Hebrew word for "wandering."

Spain came under Roman control after the Second Punic War (218–202 BCE). Jews might have moved there as free people to use its rich resources. Later, many Jews enslaved by the Romans after the defeat of Judea in 70 CE were sent to the far west, including Spain. Josephus confirmed that by 90 CE, there was already a Jewish community in Europe.

Early records that might mention Jews in Spain include Paul the Apostle's Epistle to the Romans, where he talks about going to Spain. The Mishnah, a collection of Jewish laws, also hinted at a Jewish community in Spain. Later Jewish texts like Midrash Rabbah and Pesikta de-Rav Kahana mention the Jewish community in Spain.

The Council of Elvira in the early 4th century issued rules about Christians interacting with Jews, forbidding marriage between them. This shows that Jews were already a well-established part of society.

Archaeological finds also support an early Jewish presence. A ring from Cadiz (8th–7th century BCE) has an inscription that some believe is ancient Hebrew. An amphora (a type of jar) from Ibiza (1st century) has Hebrew characters. There are also Jewish inscriptions from Tarragona and Tortosa (2nd century BCE to 6th century). A tombstone from Adra (early 3rd century) belongs to a Jewish girl.

These findings suggest that by the 3rd century, there was a strong Jewish community in Spain. Jews in the Roman Empire worked in many jobs, including farming. They had good relationships with non-Jewish people until Christianity became more dominant. The rules from the Synod of Elvira show that the presence of Jews was a concern for Catholic leaders, who wanted to keep the two communities separate.

Visigothic Rule: Hard Times for Jews (5th Century to 711 CE)

By the early 5th century, most of Spain was ruled by the Visigoths. At first, they didn't care much about different religions. But in 506, King Alaric II adopted Roman laws, which started to affect Jews.

Things changed a lot when the Visigothic royal family, led by Recared, converted to Catholicism in 587. They wanted everyone in the kingdom to be Catholic, so they became very strict with the Jews. In 589, the Third Council of Toledo decided that children of mixed Jewish-Christian marriages should be forced to be baptized. Jews were also forbidden from holding public office or having relationships with Christian women. However, not all Visigoths converted, and some Arian bishops and nobles protected the Jews.

King Sisebut (612–620) was even stricter. In 613, he ordered Jews to either convert or be expelled from Spain. Some fled to France or North Africa, but as many as 90,000 converted. Many of these new converts secretly kept their Jewish faith. When King Suintila (621–631) was more tolerant, many secret Jews returned to Judaism, and some exiles came back to Spain.

In 633, the Fourth Council of Toledo tried to deal with the problem of secret Jews. They decided that if a Christian was found to be practicing Judaism, their children would be taken away and raised by Christians. The trend of intolerance continued under King Chintila (636–639). He ordered that only Catholics could live in the kingdom and even threatened future kings who didn't follow his anti-Jewish rules.

The "problem" didn't go away. The Eighth Council of Toledo in 653 again discussed Jews. They banned all Jewish religious practices and made converted Jews promise to report anyone who returned to Judaism. They also punished nobles and clergy who helped Jews.

Still, the Jewish population remained large. King Wamba (672–680) issued limited expulsion orders. King Erwig (680–687) also struggled with the issue. The Twelfth Council of Toledo again called for forced baptism, and those who refused faced losing their property, physical punishment, exile, and slavery. In 694, Jewish children over seven were taken from their parents.

King Egica (687–702) eased the pressure on those who had been forced to convert but kept it on practicing Jews. He made economic hardships worse, like forcing Jews to sell their land at a fixed price. Jews were also forbidden from trading with Christians in Spain or overseas.

In 694, at another Council of Toledo, Jews were condemned to slavery because they were accused of plotting with the Eastern Roman Empire and Muslims. The Visigoths saw Jews as enemies. It's not clear how much Jews helped the Muslim invasion in 711, but since they were treated so badly by the Visigoths, it's not surprising they might have welcomed the Moors, who were much more tolerant. In many conquered towns, Muslims left the defense to Jews, which began the Golden Age of Spanish Jews.

Muslim Spain: A Golden Age (711 to 1492 CE)

When Tariq ibn Ziyad won his victory in 711, life for Jewish people in Spain changed a lot. Most Jews in Spain welcomed the Muslim invaders.

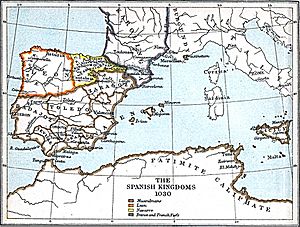

How the Moors Conquered Spain

Both Muslim and Christian stories say that Jews helped the invaders. After cities like Córdoba, Granada, Málaga, Seville, and Toledo were captured, their defense was left to Jewish and Muslim soldiers. Some accounts say Jews helped the Moors enter Toledo.

Even though Jews had some restrictions as dhimmis (non-Muslims living under Muslim rule), life under Muslim rule offered many more opportunities than under the Visigoths. Jews from all over the world saw Spain as a place of tolerance and opportunity. After the first Arab-Berber victories, especially when Abd al-Rahman I established Umayyad rule in 755, Jews from other parts of Europe and Arab lands joined the local Jewish community. This mix of different Jewish traditions made Sephardic (Spanish Jewish) culture richer. Connections with Middle Eastern Jewish communities grew stronger, and the influence of the great Jewish academies in Babylonia was at its peak.

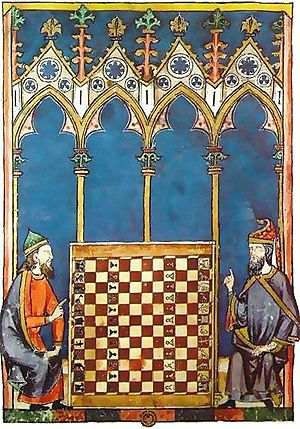

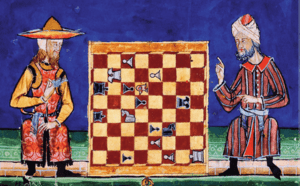

Arabic culture also had a big impact on Sephardic culture. Muslims often debated Jewish beliefs, which made Jews think more deeply about their own scriptures. Many Jewish scholars started writing in Arabic. This allowed educated Jews to access Arabic scientific and philosophical knowledge, including ideas from ancient Greek culture. The Arab focus on grammar also made Jews more interested in studying language. Arabic became the main language for Jewish science, philosophy, and daily business.

At first, the many conflicts among Muslim groups kept Jews out of politics. But in the first two centuries before the Golden Age, Jews became more active in professions like medicine, trade, finance, and farming.

By the 9th century, some Jewish people felt confident enough to try to convert former Jews who had become Catholic.

The Golden Age in Córdoba

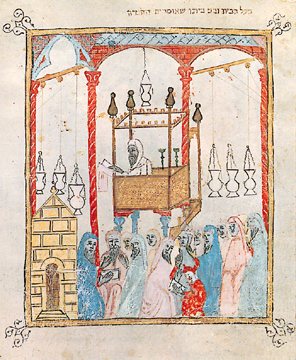

The first period of great prosperity for Jews happened under Abd ar-Rahman III (882–955), the first Caliph of Córdoba. This Golden Age is closely linked to his Jewish advisor, Hasdai ibn Shaprut (882–942). Hasdai started as a court doctor but later managed customs and foreign trade. He even wrote to the Khazars, a kingdom that had converted to Judaism.

Abd al-Rahman III supported Arabic learning, making Spain a center for language studies. Because of this, Hebrew studies also grew. With Hasdai's help, Córdoba became a hub for Jewish scholars.

Hasdai, who was also a poet, supported other Jewish writers. They wrote about religion, nature, politics, and more. Hasdai brought many talented people to Córdoba, like Dunash ben Labrat, who created new Hebrew poetry styles, and Menahem ben Saruq, who wrote the first Hebrew dictionary. Famous poets of this time included Solomon ibn Gabirol, Yehuda Halevi, Samuel Ha-Nagid ibn Nagrela, and Abraham and Moses ibn Ezra.

For the only time between Biblical times and the modern state of Israel, a Jew (Samuel ha-Nagid) led a Jewish army.

Hasdai also helped Jews around the world by using his influence to protect them, for example, by writing to the Byzantine Princess Helena to ask for protection for Jews under Byzantine rule.

The achievements of Jewish scholars in Spain also influenced non-Jews. Ibn Gabirol's philosophical work, Fons Vitae ("The Source of Life"), was so admired that many thought a Christian wrote it. Jews were also active in fields like astronomy, medicine, logic, and mathematics. Studying the natural world was seen as a way to understand God better. Spain also became a major center for Jewish philosophy.

Jewish scholars were also important translators. They translated Greek texts into Arabic, Arabic into Hebrew, and Hebrew and Arabic into Latin. By translating these works, Jewish scholars in Spain helped bring science and philosophy, which were key to the Renaissance, to the rest of Europe.

Taifas, Almoravids, and Almohads

In the early 11th century, the central government in Córdoba broke down. Instead, many small, independent kingdoms called taifas appeared. This actually created more opportunities for Jewish and other skilled people. Christian and Muslim rulers in these smaller centers valued Jewish scientists, doctors, traders, poets, and scholars.

Among the most famous Jews who served as advisors (viziers) in Muslim taifas were the ibn Nagrelas. Samuel Ha-Nagid ibn Nagrela (993–1056) served the King of Granada for thirty years. He was a policy maker, a military leader (one of only two Jews to command Muslim armies), and a poet. His son Joseph ibn Naghrela also became a vizier but was killed in the 1066 Granada massacre. Other Jewish viziers served in Seville, Lucena, and Saragossa.

The 1066 Granada massacre was a violent attack on Jews in Granada. A Muslim crowd stormed the royal palace, killed Joseph ibn Naghrela, and then attacked 1500 Jewish families, killing about 4,000 Jews.

This event was an early sign that the Golden Age was ending. The status of Jews declined because of the growing influence of strict Islamic groups from North Africa.

After Toledo fell to Christians in 1085, the ruler of Seville asked for help from the Almoravides. This strict group disliked the liberal culture of Muslim Spain, especially that non-Muslims held positions of power. The Almoravides tried to make Muslim Spain more like their strict version of Islam. Many Jews were forced to convert, but Sephardic culture didn't completely disappear. Some Jewish communities, like Lucena, managed to avoid conversion by paying bribes. As the Almoravides became more settled, their policies towards Jews became less harsh.

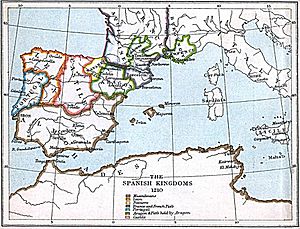

Wars in North Africa eventually forced the Almoravides to leave Spain. As Christians advanced, Muslims in Spain again asked for help from North Africa, this time from the Almohads. The Almohads, who took control of much of Muslim Spain by 1172, were even more extreme than the Almoravides. They treated non-Muslims very harshly. Jews and Christians were expelled from Morocco and Muslim Spain. Many Jews chose to leave rather than convert or die. Some, like the family of Maimonides, fled to more tolerant Muslim lands, while others went north to the growing Christian kingdoms.

Meanwhile, the Reconquista (Christian reconquest) continued in the north. By the early 12th century, conditions for some Jews in the Christian kingdoms were improving. Christian leaders needed the help of Jews to rebuild towns after the Muslim rule broke down. Jews knew the language and culture of the enemy, were skilled diplomats and professionals, and wanted relief from the harsh conditions in Muslim areas. This made them very valuable to the Christians. So, as life in Muslim Spain got worse, more Jews moved to Christian areas.

However, Jews moving north were not completely safe. Old prejudices combined with new ones. People suspected them of helping Islam, and Jews from Muslim areas spoke Arabic. Still, many newly arrived Jews in the north did well in the late 11th and early 12th centuries, often owning land and vineyards.

Life had come full circle for the Jews of Spain. As conditions became harder in Muslim areas, Jews again looked to another culture for help. Christian leaders in reconquered cities gave them a lot of freedom, and Jewish learning grew again as communities became larger and more important. However, the Jews of the Reconquista never reached the same level of greatness as those of the Golden Age.

Jewish Life in Christian Kingdoms (974–1300 CE)

Early Christian Rule (974–1085)

At first, Catholic rulers, like the counts of Castile and the first kings of León, treated Jews harshly. They destroyed synagogues and killed Jewish teachers during their fights against the Moors. However, rulers slowly realized they couldn't afford to make Jews their enemies, especially since they were surrounded by powerful foes. Garcia Fernandez, Count of Castile, in 974, gave Jews many of the same rights as Catholics. The Council of Leon (1020) also adopted similar rules. In Leon, many Jews owned land and worked in farming, winemaking, and crafts. They lived peacefully with Christians. Because of this, the Council of Coyanza (1050) had to bring back an old law forbidding Jews and Christians from living or eating together.

A Time of Tolerance and Jewish Migration (1085–1212)

Ferdinand I of Castile set aside some Jewish taxes for the Church. Alfonso VI, who conquered Toledo in 1085, was tolerant and kind to Jews, earning praise from Pope Alexander II. To encourage wealthy and hardworking Jews to leave Muslim areas, he offered them special rights. In 1076, he granted Jews full equality with Catholics and even noble rights. In return, Jews willingly served him and the country. Alfonso's army included 40,000 Jews. Because of his favoritism, Pope Gregory VII warned him not to let Jews rule over Catholics, which made Christians angry. After a battle in 1108, an anti-Jewish riot broke out in Toledo; many Jews were killed, and their homes and synagogues were burned. Alfonso planned to punish those responsible but died in 1109. After his death, more attacks happened in other towns.

Alfonso VII at first limited Jewish rights but soon became friendlier, giving them back their old privileges and even new ones, making them equal to Catholics. Judah ben Joseph ibn Ezra was very influential with the king. After conquering Calatrava in 1147, the king put Judah in charge of the fortress and later made him his court chamberlain. Because of Judah, the king allowed Jews who had fled from the Almohades to settle in Toledo and other places, where new communities were formed.

After King Sancho III's short reign, a war broke out between Fernando II of León and the kings of Aragon and Navarre. Jews fought in both armies and were later put in charge of fortresses. Alfonso VIII of Castile (1166–1214) gave Jews even more influence. He was helped by the beautiful Jewish woman Rachel of Toledo. When the king lost a battle, people blamed his relationship with Rachel, and she and her family were murdered in Toledo. After this defeat, the Muslim leader threatened Christian Spain. The wealthy Jews of Toledo, especially Joseph ben Solomon ibn Shoshan, greatly helped the king in this war.

A Turning Point for Jews (1212–1300)

When Crusaders arrived in Toledo, they attacked and robbed Jews. Only the knights stopped them from killing all the Jews. After a major battle in 1212, Alfonso entered Toledo victoriously, and Jews welcomed him. Before he died in 1214, the king issued a law that was good for Jews.

A major change for Jews in Spain happened under Ferdinand III of Castile (who united León and Castile) and James I of Aragon. The clergy's efforts against Jews grew stronger. Spanish Jews, like those in France, were forced to wear a yellow badge on their clothes to distinguish themselves from Catholics and prevent mixing. However, some Jews, like Vidal Taroç, were allowed to own land.

In 1250, Pope Innocent IV issued a rule that Jews could not build new synagogues without special permission. It also made it illegal for Jews to try to convert others. They were forbidden from associating with Catholics, living in the same house, eating or drinking with them, or using the same bath. Catholics could not use medicine prepared by Jews. Every Jew had to wear the badge, though the king could make exceptions. Jews were also forbidden from appearing in public on Good Friday.

Jewish Communities in 1300

By 1300, Jews in Spain were citizens of the kingdoms where they lived, like Castile, Aragón, and Valencia. They owned land and worked in farming, industry, trade, and crafts. Their hard work made them wealthy, and their knowledge earned them respect. But this success made other people jealous and angered the clergy, causing Jews much suffering. Kings, especially in Aragon, saw Jews as their property and protected them because they were useful, especially for taxes. Jews were like other commoners, serving the king.

Around 1300, there were about 120 Jewish communities in Catholic Spain, with around half a million or more Jews, mostly in Castile. Catalonia, Aragon, and Valencia had fewer Jews.

While Spanish Jews worked in many fields, it was the money-lending business that brought some of them wealth and influence. Kings, nobles, and farmers all needed money and could only get it from Jews, who charged high interest. This business, which Jews were often forced into to pay high taxes and loans to the kings, led to them being employed in special roles like tax collectors.

Jews in Spain had their own political system. They mostly lived in special Jewish neighborhoods called Juderias. They had their own administration. In Castile, the "rab de la corte" (court rabbi) or "rab mayor" (chief rabbi) was the main link between the Jewish communities and the state. These chief rabbis were appointed by the kings, often based on their service to the state rather than their religious knowledge.

Challenges and Massacres (1300–1391)

At the beginning of the 14th century, life for Jews became very uncertain across Spain as antisemitism grew. Many Jews left Castile and Aragon. Things improved under the reigns of Alfonso IV and Peter IV of Aragon, and the young Alfonso XI of Castile (1325).

Peter of Castile, Alfonso XI's son, was relatively kind to Jews. Under him, Jews became very influential, often shown by the success of his treasurer, Samuel ha-Levi. Because of this, the king was sometimes called "the heretic" or "the cruel." Peter was young when he became king in 1350 and surrounded himself with Jews, leading his enemies to mock his court as "a Jewish court."

However, a civil war soon broke out. In 1355, Henry II of Castile and his brother led a mob that attacked the Jewish quarter of Toledo, stealing from warehouses and killing about 1200 Jews. The main Jewish quarter was defended by Jews and knights loyal to the King. After John I of Castile became king, conditions for Jews seemed to get a bit better, with John I even making special legal exceptions for some Jews.

The kinder Peter was to the Jews, the more his half-brother Henry hated them. When Henry invaded Castile in 1360, he murdered all Jews in Nájera and allowed those in Miranda de Ebro to be robbed and killed.

Violent Attacks in 1366

Jews remained loyal to King Peter and fought bravely in his army. The king always showed his support for them. Despite this, they suffered greatly. Towns like Villadiego and Aguilar de Campoo were completely destroyed. The people of Valladolid, who supported Henry, robbed Jews, destroyed their homes and synagogues, and tore up their holy books. Other communities faced similar fates, and 300 Jewish families from Jaén were taken prisoner to Granada. A writer at the time, Samuel Zarza, said the suffering was extreme, especially in Toledo, where 8,000 people died from hunger and war. This civil war ended with Peter's death in 1369.

When Henry II became king, a time of suffering and intolerance began for Castilian Jews, leading to their eventual expulsion. Long wars had ruined the land, people were used to lawlessness, and Jews became poor.

Despite his dislike for Jews, Henry still used their services. He employed wealthy Jews, like Samuel Abravanel, as financial advisors and tax collectors. However, the clergy's power grew, and they stirred up anti-Jewish feelings at the Cortes of Toro in 1371. They demanded that Jews be kept away from nobles, not hold public office, live separately from Catholics, not wear fancy clothes or ride mules, wear a special badge, and not use Catholic names. The king agreed to some of these demands but allowed Jews to have religious debates and their own justice system for crimes. This right was taken away later by John I, Henry's son, after some Jews used it to get permission to execute a royal favorite.

New Laws Against Jews

In 1380, the Cortes of Soria ruled that rabbis could not punish Jews with death, expulsion, or excommunication, but Jews could still choose their own judges for civil cases. After an accusation that Jewish prayers cursed Catholics, the king ordered them to remove the offensive parts from their prayer books. Anyone who converted a Muslim or a person of another faith to Judaism would become a slave. Jews no longer dared to appear in public without the badge, and they were constantly in danger. Against his will, John had to issue an order in 1385 forbidding Jews from working as financial agents or tax collectors for the royal family or nobles. The Council of Palencia also ordered the complete separation of Jews and Catholics.

Violent Attacks and Mass Conversions in 1391

The execution of Joseph Pichon and the fiery speeches by Archdeacon Ferrand Martínez in Seville quickly made the public hate Jews even more. The weak King John I died in 1390, and his 11-year-old son took over. The council ruling for the young king was powerless. Ferrand Martínez continued to encourage people to kill or baptize Jews. In January 1391, Jewish leaders in Madrid learned that riots were expected in Seville and Córdoba.

A revolt broke out in Seville in 1391. On June 6, the mob attacked the Jewish quarter of Seville from all sides and killed 4000 Jews. The rest were forced to be baptized to save their lives.

Jewish writers of the time, like Isaac ben Sheshet and Hasdai Crescas, described these terrible events. According to Hasdai Crescas, the persecution started in Seville in June 1391 and spread to Córdoba, Toledo, Mallorca, Barcelona, and Valencia. Many Jews died as martyrs, while others converted to save themselves.

From Persecution to Expulsion (1391–1492)

The year 1391 was a turning point for Jews in Spain. The persecution led directly to the Spanish Inquisition, which was created 90 years later to watch over converted Jews and fight heresy. A very large number of Jews converted to Catholicism to escape death. Some historians say over half of Spain's Jews converted, leaving only about 100,000 openly practicing Jews by 1410. Many wealthy and educated Jews converted. Some, like Solomon ha-Levi (who became Paul de Burgos), even became bitter enemies of their former Jewish community.

After the violent events of 1391, the public's hatred of Jews continued. The Cortes (parliaments) of Madrid and Valladolid (1405) focused on complaints against Jews. Henry III had to forbid Jews from charging high interest and limited trade between Jews and Catholics. He also cut in half the debts Christians owed to Jews. The king, whose mother hated Jews, showed no friendship towards them. Although he regretted that many Jews left Spain for Málaga, Almería, and Granada (where Moors treated them well), he still made Jews wear a special badge and forbade them from dressing like other Spaniards.

Many Jews from Valencia, Catalonia, and Aragon fled to North Africa, especially Algiers.

Laws Against Jews

At the request of a Catholic preacher named Ferrer, a law with 24 rules was issued in January 1412 in the name of the child-king John II of Castile. This law aimed to make Jews poor and humiliate them further. They were ordered to live only in enclosed Jewish quarters. They were forbidden from practicing medicine, surgery, or chemistry, and from selling food like bread, wine, or meat. They could not work in crafts or trades, hold public office, or act as money brokers. They were not allowed to hire Catholic servants or visit Catholics. Catholic women were forbidden from entering Jewish quarters. Jews had no self-rule and could not collect taxes for their communities without royal permission. They could not use the title "Don," carry weapons, or trim their beards or hair. Jewish women had to wear plain, long cloaks. Jews were forbidden from leaving the country, and anyone who helped a fleeing Jew was heavily fined. These strict laws were designed to force Jews to convert to Catholicism.

The persecution of Jews became systematic. In 1415, a Papal Bull (a special order from the Pope) was issued, which largely matched the laws already in place. This bull forbade Jews and new converts from studying the Talmud or reading anti-Catholic writings. They could not say the names of Jesus, Mary, or the saints. They could not make or accept church items. Each community could only have one synagogue. Jews lost all rights to their own justice system. They could not hold public office or work in many professions like doctors or pharmacists. They were forbidden from baking or selling matzot. They had to wear the badge at all times, and three times a year, all Jews over 12 had to listen to a Catholic sermon.

When the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella became rulers, they took steps to separate Jews from both converts and other Spaniards. In 1480, all Jews were ordered to live in special neighborhoods. The same year, the Spanish Inquisition was established, mainly to deal with converts suspected of secretly practicing Judaism. Even though both monarchs had Jewish ancestors and advisors, they were very intolerant. Ferdinand ordered all converts to make peace with the Inquisition by 1484 and got a special order from Pope Innocent VIII to return all fleeing converts to the Spanish Inquisition. One reason for their harshness was that they no longer feared Jews and Moors uniting, as the Muslim kingdom of Granada was about to fall. However, they had promised the Jews of Granada that they could keep their rights if they helped overthrow the Moors. This promise was broken by the expulsion decree.

The bans, persecution, and eventual mass emigration of Jews from Spain and Portugal likely hurt the Spanish economy. Jews and non-Catholic Christians often had better math skills than the Catholic majority, possibly because Jewish religious teachings strongly focused on education. Even when Jews were forced out of their skilled jobs, their math advantage remained. However, during the Inquisition, these skills didn't spread much to the rest of society because of forced separation and Jewish emigration, which was bad for economic growth.

Jewish Buildings

A few synagogues from before the expulsion still exist, including the Synagogue of Santa María la Blanca and the Synagogue of El Tránsito in Toledo, the Córdoba Synagogue, the Híjar Synagogue, the Old main synagogue, Segovia and the Synagogue of Tomar.

The Expulsion of Jews from Spain

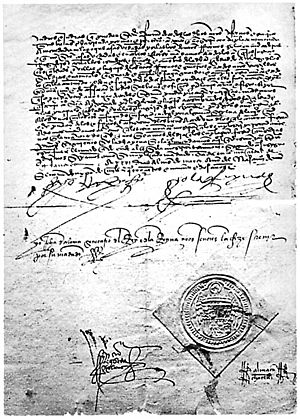

A few months after the fall of Granada, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella issued an order called the Alhambra Decree on March 31, 1492. It commanded all Jews, no matter their age, to leave the kingdom by July 31. They were allowed to take their belongings, but not gold, silver, or money.

The reason given for this action was that many converts were returning to Judaism because they lived close to unconverted Jews, who kept Jewish knowledge and practices alive.

It is said that Isaac Abarbanel, a prominent Jewish leader, offered the king and queen a huge sum of money (600,000 crowns) to cancel the order. But Tomás de Torquemada, the head inquisitor, reportedly stopped them, asking if they would betray their Lord for money like Judas. Regardless of whether this story is true, the court showed no mercy, and the Jews of Spain prepared for exile. In some places, like Vitoria, they gave their cemeteries to the city to prevent them from being disrespected. The Jewish community of Segovia spent their last three days in the Jewish cemetery, mourning their loved ones.

How Many Jews Were Expelled?

The exact number of Jews expelled from Spain is debated. Early accounts gave very high numbers, but by the time of the expulsion, most Jews had already converted to Catholicism. Recent studies suggest that between 50,000 and 80,000 practicing Jews were expelled from Spain.

Expulsions Across Europe

Expelling Jewish populations was a common trend in European history. From the 13th to the 16th century, at least 15 European countries expelled their Jewish communities. The expulsion from Spain followed expulsions from England, France, and Germany, and was followed by at least five more expulsions elsewhere.

Conversos: Secret Jews

After the expulsion, the history of Jews in Spain became the history of the conversos (those who had converted to Catholicism). Their numbers had grown to possibly 300,000. For three centuries after the expulsion, Spanish conversos were suspected by the Spanish Inquisition, which executed over 3,000 people between 1570 and 1700 for heresy, including practicing Judaism in secret. They also faced discriminatory laws called "limpieza de sangre" (purity of blood), which required Spaniards to prove they had "old Christian" backgrounds to hold certain positions of power. During this time, hundreds of conversos escaped to countries like England, France, and the Netherlands, or converted back to Judaism, becoming part of the Western Sephardic communities.

Conversos played an important role in the Revolt of the Comuneros (1520–1522), a popular uprising against the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

Modern Jewish Life (1858 to Today)

Small numbers of Jews began arriving in Spain in the 19th century, and synagogues opened in Madrid.

Moroccan Jews, who had faced oppression over centuries, welcomed Spanish troops when the Spanish protectorate in Morocco was established. General Franco met with some Sephardic Jews and spoke well of them.

By 1900, excluding Ceuta and Melilla, about 1,000 Jews lived in Spain.

Spanish historians became interested in the Sephardic Jews and their language, Judaeo-Spanish. They rediscovered the Jews of Northern Morocco who still spoke this language and practiced old Spanish customs.

The government of Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923–1930) allowed a certain number of Sephardic Jews to gain Spanish citizenship starting in 1924. This was for those who had been under Spanish protection while living in the Ottoman Empire. This law was later used by some Spanish diplomats to save Sephardic Jews from persecution during the Holocaust.

Before the Spanish Civil War, about 6,000–7,000 Jews lived in Spain, mostly in Barcelona and Madrid.

Spanish Civil War and World War II

During the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), synagogues were closed, and Jewish worship was held in private homes. Jewish public life restarted in 1947 with the arrival of Jews from Europe and North Africa.

In the early years of World War II, Spain allowed many Jewish refugees to pass through, especially those fleeing Nazi deportations from occupied France. Many historians note the irony of Jews seeking safety in a country where they hadn't been allowed to live openly for centuries.

Throughout World War II, Spanish diplomats under the Franco government protected Eastern European Jews, especially in Hungary. Jews who claimed Spanish ancestry were given Spanish documents without needing to prove their case. They either left for Spain or survived the war with their new legal status.

As the war turned, Spanish diplomacy became more helpful to Jews. Ángel Sanz Briz, the Spanish head of mission in Budapest, saved thousands of Jews in Hungary by giving them Spanish citizenship, placing them in safe houses, and teaching them basic Spanish so they could pretend to be Sephardic. Spanish diplomats tried to balance helping Jews with avoiding German anger.

When Sanz Briz had to flee Budapest, an Italian diplomat, Giorgio Perlasca, pretended to be the new Spanish Ambassador. He continued Spanish protection of Hungarian Jews until the war ended.

While Spain helped Jews escape deportation more than most neutral countries, there's debate about its wartime attitude. Franco's government, despite disliking Zionism, didn't seem to share the Nazis' extreme anti-Semitic views. About 25,000 to 35,000 refugees, mostly Jews, were allowed to pass through Spain to Portugal and beyond.

Some historians say this shows Franco's regime was humane, while others point out that it mainly allowed transit, not settlement. After the war, Franco's regime was welcoming to some who had been responsible for the deportation of Jews, like former Nazis and Fascists.

In 1941, José María Finat y Escrivá de Romaní, Franco's chief of security, ordered all provincial governors to list all Jews in their areas. This list of 6,000 names was later given to Heinrich Himmler. After Germany's defeat, the Spanish government tried to destroy evidence of cooperation with the Nazis, but this order survived.

Around the same time, synagogues reopened, and Jewish communities could practice their faith more openly.

In 1948, the official state bulletin published a list of Sephardic family names from Greece and Egypt that should receive special protection.

The Alhambra Decree that had expelled the Jews was officially canceled on December 16, 1968.

Spain and Israel

The former Israeli ambassador Shlomo Ben-Ami remembers the Spanish Legion escorting his family from Tangiers, Morocco, to Israeli ships. During Spain's move to democracy, recognizing Israel was an important step towards modernization.

The Spanish government under Felipe González established relations with Israel in 1986. Spain tries to act as a bridge between Israel and Arab nations, as seen in the Madrid Conference of 1991.

Between 1948 and 2010, 1,747 Spanish Jews moved to Israel.

Modern Jewish Community

Today, there are around 50,000 Spanish Jews. The largest communities are in Barcelona and Madrid, each with about 3,500 members. Smaller communities exist in Alicante, Málaga, Tenerife, Granada, Valencia, Benidorm, Cadiz, Murcia, and other places.

Melilla has an old community of Sephardic Jews. The city of Murcia has a growing Jewish community and a local synagogue. Kosher olives are produced there and exported worldwide. A new Jewish school has also opened in Murcia due to the growing Jewish population.

The modern Jewish community in Spain mainly consists of Sephardim from North Africa, especially former Spanish colonies. In the 1970s, many Argentine Jews (mostly Ashkenazim) also moved to Spain, fleeing military rule. With the creation of the European Union, Jews from other European countries moved to Spain for its weather, lifestyle, and lower cost of living. Some Jews see Spain as an easier place for retirees and young people.

In recent years, Reform and liberal Jewish communities have also emerged in cities like Barcelona and Oviedo.

Some famous Spaniards of Jewish descent include businesswomen Alicia and Esther Koplowitz, politician Enrique Múgica Herzog, and Isak Andic, founder of the clothing company Mango.

There are rare cases of people converting to Judaism, like the writer Jon Juaristi. Today, some Jewish groups in Spain encourage descendants of the Marranos to return to Judaism, leading to a small number of conversions.

Like other religious groups in Spain, the Federation of Jewish Communities in Spain (FCJE) has agreements with the Spanish government. These agreements cover the status of Jewish clergy, places of worship, teaching, marriages, holidays, tax benefits, and preserving heritage.

In 2014, residents of a Spanish village called Castrillo Matajudios voted to change its name. "Mata" is a common part of Spanish place names meaning "forested patch," but it also means "kill." This caused confusion, making the name sound like "kill the Jews." The name was changed back to its older name, Castrillo Mota de Judíos (Castrillo Hill of the Jews), which is less confusing.

2014–2019 Citizenship Law

In 2014, Spain announced that descendants of Sephardic Jews expelled by the Alhambra Decree of 1492 could apply for Spanish citizenship. They didn't have to move to Spain or give up their other citizenships. The law ended on October 1, 2019. By then, the justice ministry had received 132,226 applications and approved 1,500. To be approved, applicants had to pass tests in Spanish language and culture, prove their Sephardic heritage, show a special connection with Spain, and have a notary certify their documents.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de los judíos en España para niños

In Spanish: Historia de los judíos en España para niños

- Foreign relations of Portugal

- Israel–Spain relations

- Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain

- History of the Jews in Portugal

- History of the Jews under Muslim rule

- Jacob ibn Jau

- Jewish community of Calatayud

- Anusim

- Converso

- Crypto-Judaism

- Marrano

- Persecution of Jews

- Samuel Toledano

- Sephardi Jews

- Sephardic law and customs

- Jews of Catalonia

- Portuguese Inquisition

- Spanish and Portuguese Jews

- Spanish Inquisition

- Alhambra Decree

- Pallache family

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |