William Jackson Hooker facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

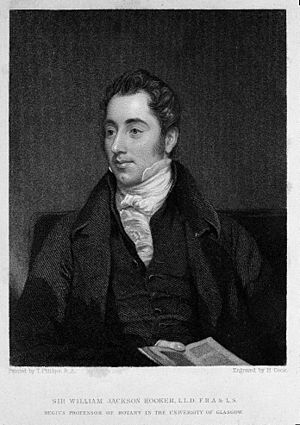

Sir William Jackson Hooker

|

|

|---|---|

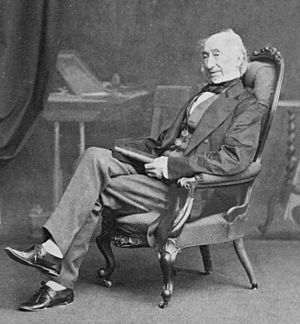

Portrait by Spiridione Gambardella

|

|

| Born | 6 July 1785 |

| Died | 12 August 1865 (aged 80) London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, United Kingdom

|

| Citizenship | British |

| Alma mater | Norwich School |

| Known for | Founding the Herbarium at Kew |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Botany |

| Institutions | |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Hook |

| Signature | |

|

|

Sir William Jackson Hooker (6 July 1785 – 12 August 1865) was an important English botanist and artist. He is famous for becoming the first director of Kew in 1841. At Kew, he started the Herbarium, a collection of dried plant specimens, and made the gardens much bigger.

Hooker was born and grew up in Norwich, England. He inherited money, which allowed him to travel and study natural history, especially plants. He wrote about his trip to Iceland in 1809, even though most of his notes were lost. In 1815, he married Maria Turner and lived in Halesworth for 11 years. There, he created a large plant collection that was well-known to other botanists.

He later became a professor of Botany at Glasgow University. In 1841, he became the Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. He made Kew Gardens much larger, built new glasshouses, and created an arboretum (a collection of trees) and a museum about useful plants. He wrote many books, including The British Jungermanniae (1816) and Flora Scotica (1821).

He passed away in 1865 from a throat infection. His son, Joseph Dalton Hooker, followed in his footsteps and became the next Director of Kew Gardens.

Contents

Early Life and Plant Discoveries

William Jackson Hooker was born on July 6, 1785, in Norwich. From a young age, he loved entomology (the study of insects), reading, and natural history.

In 1805, Hooker found a rare moss called Buxbaumia aphylla near Norwich. He showed it to Sir James Edward Smith, a famous botanist. Smith encouraged him to talk to another botanist, Dawson Turner, about his discovery.

When he turned 21, Hooker received money from his godfather. This allowed him to travel and focus on his passion for natural history. He also spent time studying birds and insects in Norfolk. In 1805, a type of weevil (a small beetle) was named Omphalapion hookerorum after him and his brother Joseph, because of their excellent work in natural history.

In 1806, he met Sir Joseph Banks, a very important scientist and president of the Royal Society. Hooker became a member of the Linnean Society of London that same year.

Friends and Mentors

As a young man, Hooker became friends with leading naturalists in England. These included James Edward Smith, who owned the plant collections of Carl Linnaeus, and Dawson Turner, a botanist and collector.

In 1807, Hooker was bitten by an adder (a type of snake) and was badly hurt. He recovered at Dawson Turner's house. After he got better, he traveled to Scotland with Turner and his wife. In 1808, he found a new moss species, Andreaea nivalis, on Ben Nevis, a large mountain.

Hooker also drew pictures for James Edward Smith's paper about a new group of mosses called Hookeria, which was named after William and his brother Joseph. He also drew for Dawson Turner's four-volume book Historia Fucorum.

For about ten years, Hooker worked as a manager at a brewery in Halesworth. He lived at the brewery house, which had a big garden and a greenhouse where he grew orchids. However, he wasn't very good at business.

Travels and Expeditions

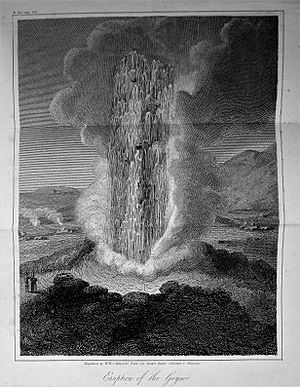

With his own money, Hooker was able to go on expeditions. His first plant-collecting trip abroad was to Iceland in the summer of 1809. He sailed on a ship called the Margaret and Anne.

On his way back, the ship caught fire, and most of his drawings and notes were destroyed. Luckily, Hooker and everyone else on board were rescued. Sir Joseph Banks later let Hooker use his own papers to help him. With these, and his good memory, Hooker published a book about Iceland, its people, and its plants. It was called A Journal of a Tour in Iceland (1809).

In 1810–11, he planned a trip to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) but had to cancel it due to political problems there. In 1812, he became a member of the Royal Society of London.

In 1814, he traveled around Europe for nine months. He visited Paris, Switzerland, southern France, and Italy, where he studied plants and met other botanists. The next year, he married Maria Sarah Turner. They settled in Halesworth, and his collection of plants became famous worldwide.

Career in Glasgow

In 1820, William Hooker became the professor of botany at the University of Glasgow. He took over a small botanic garden that didn't have much money or many plants. He had never taught before, and he needed to learn more about some parts of botany.

He quickly became a popular teacher. His lectures were clear and interesting, and even army officers came to listen. For 15 years, he taught a summer course on botany that all medical students had to take. The rest of the year, he studied, worked on his books, and wrote to other botanists.

His classroom had plant drawings to help students, and he organized trips to study plants outdoors. The number of students grew from 30 in 1820 to 130 ten years later.

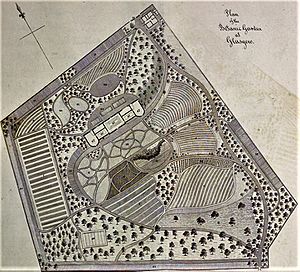

His time in Glasgow was very busy and productive. In 1821, he published Flora Scotica for his students. He also received a doctorate from Glasgow University. He worked with Thomas Hopkirk to create the Royal Botanic Institution of Glasgow and to design the Botanic Gardens.

Under Hooker's leadership, the Botanic Gardens became very successful and well-known around the world. He used his many friends and contacts to get new plants for the garden, often from naturalists or traveling students. Experts said that Glasgow's garden was as good as any in Europe.

While in Glasgow, he wrote many important books, including Flora Londinensis, British Flora, and Exotic Flora. He also worked on Curtis's Botanical Magazine.

In 1836, Hooker was made a Knight, which is a special honor, for his work in Glasgow and his contributions to botany.

Director of Kew Gardens

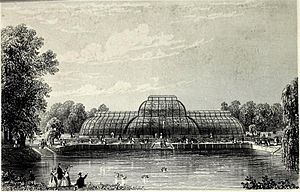

The Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew started when the royal estates of Richmond and Kew joined in 1772. The gardens were expanded by Princess Augusta and later by King George III. Over time, the plant collections at Kew had slowly declined. In 1838, a government review suggested that Kew should become a national botanical garden.

In April 1841, William Hooker was chosen as Kew's first full-time Director. He had wanted this job for a long time. He started with a salary of £300 a year. He was perfect for the job because he was a professional botanist, an artist, a leader, and knew a lot about plants from all over the world.

Under Hooker, the gardens grew a lot. They expanded from about 11 acres to 15 acres in 1841. He also added an arboretum of 270 acres, built many new glasshouses, and started a museum of economic botany (plants useful to people). In 1843, the famous Palm House was built at Kew. For the first time, the gardens and glasshouses were open to the public every day, and people could walk around freely. Sir William himself often walked around, offering advice.

Hooker lived with his family at West Park, a large house at Kew. His library, with 13 rooms of books, was open to botanists from all over the world. Many important people visited Kew, including Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. By 1865, the year Hooker died, over half a million people visited Kew Gardens.

Under Hooker's leadership, Kew became the most important center for plant knowledge in the world. Staff recommended by him joined expeditions or worked for botanical gardens everywhere. He was always asked for advice when the government had questions about plants. New plants grown at Kew were sent to gardens in Britain and to botanical gardens overseas, sometimes to be grown as crops.

Family Life

In June 1815, William Hooker married Maria Sarah Turner. Maria was an artist who collected mosses. She and her sister Elizabeth drew pictures of mosses for her husband's books.

They had five children. Their son, William Dawson Hooker, became a doctor and naturalist. He moved to Jamaica to practice medicine but sadly died at age 24. Their other son, Joseph Dalton Hooker, also became a botanist. He worked as an assistant director at Kew for 10 years before taking over from his father as director in 1865. They also had three daughters: Maria, Elizabeth, and Mary Harriet, who passed away at age sixteen.

Works and Discoveries

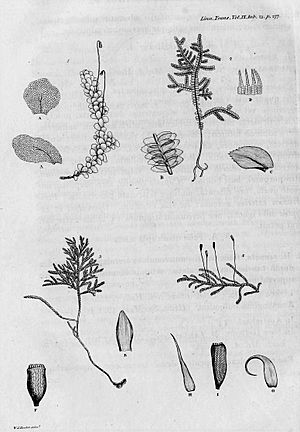

Hooker studied mosses, liverworts (small green plants), and ferns. He published his first major work, British Jungermanniae, about liverworts in 1816. He also wrote descriptions for a new edition of William Curtis's Flora Londinensis.

He published more than 20 important books about plants over 50 years. Some of his key works include:

- British Jungermanniae (1816)

- Musci Exotici (1818–1820), about new foreign mosses

- Flora Scotica (1821)

- The British Flora (1830)

- Flora Borealis Americana (1840), about plants in northern British America

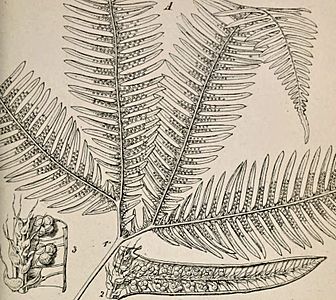

- Species Filicum (1846–1864), about ferns

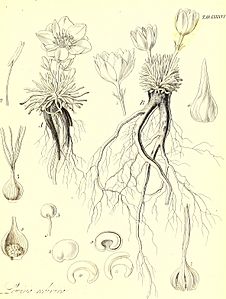

Examples of his Illustrations

-

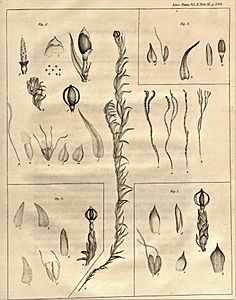

Bromelia aquilegia, from The Paradisus Londinensis (1805)

-

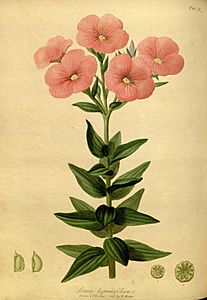

Linum hypericifilum from The Paradisus Londinensis (1807)

-

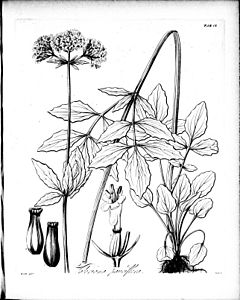

Valeriana pauciflora, from Flora boreali-Americana (1840)

-

Lewisia rediviva, from The Botany of Captain Beechey's Voyage (1841)

Plants Named After Hooker

Many plants have the Latin name hookeri in their scientific name. This is to honor William Jackson Hooker. Some examples include:

- Allium hookeri

- Anthurium hookeri

- Arctostaphylos hookeri

- Drosera hookeri

- Epiphyllum hookeri

- Iris hookeri

- Lithops hookeri

- Ozothamnus hookeri

- Pachyphytum hookeri

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |