Wari culture facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Huari Culture

Wari

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th century–10th century | |||||||||||||

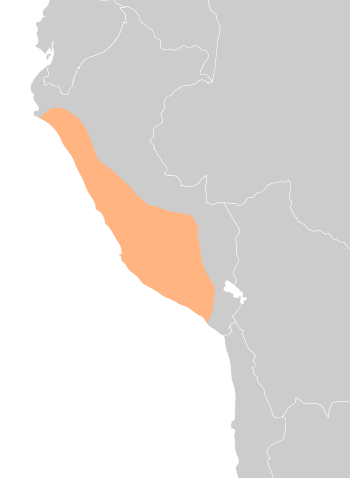

Expansion and area of influence of the Wari Empire around 800 AD

|

|||||||||||||

| Capital | Huari | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Aymara, others( Quechua,Culli, Quignam, Mochica) | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Andean beliefs (Staff God) | ||||||||||||

| Government | unknown | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Horizon | ||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

6th century | ||||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

10th century | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Today part of | Peru | ||||||||||||

The Wari (Spanish: Huari) were an important ancient civilization. They lived in the Andes mountains and along the coast of what is now Peru. This culture thrived from about 500 to 1000 AD. This time is known as the Middle Horizon period in ancient Peru.

The main city of the Wari was also called Wari. It is located about 11 kilometers (7 miles) northeast of the modern city of Ayacucho, Peru. This city was the heart of a civilization that spread across much of the highlands and coast of Peru. Other well-preserved Wari sites include the recently found Northern Wari ruins near Chiclayo. There is also Cerro Baúl in Moquegua. Another famous Wari site is Pikillaqta ("Flea Town"), located southeast of Cusco.

Experts still discuss how much control the Wari had over the Central Coast. Some believe the Wari fully ruled these areas. Others think the people on the Central Coast were strong trading states. They might have traded with the Wari without being politically controlled by them.

Contents

History of the Wari

Around 600 AD, the Wari empire began to grow. They took control of many small villages in Peru's Carahuarazo Valley. When the Wari arrived, some villages were left empty. One village was even partly destroyed to build a Wari government center called Jincamocco.

The Wari brought new farming methods to the area. They taught people how to use terracing agriculture. This meant growing crops on steps built into hillsides. This changed the main crops from just root vegetables to both root vegetables and maize (corn). Wari storage buildings have been found near farms. These were likely used to store the harvested crops. The Wari stayed in the Carahuarazo Valley until about 800 AD. After that, most sites in the valley were left empty.

Early on, the Wari expanded their land to include Pachacamac. This was an ancient place where people went to ask for advice from a spiritual leader. Even though the Wari took control, Pachacamac seemed to stay mostly independent. Later, the Wari became powerful in much of the land once held by the Moche and later the Chimu cultures.

People debate why the Wari expanded so much. Some think it was to spread their religion. Others believe it was to share their farming knowledge, especially terracing. It could also have been through military conquest. War and the threat of violence often helped ancient empires grow and stay strong, and the Wari were no different. Signs of violence in Wari culture can be seen at the city of Conchopata.

Around 800 AD, the Wari culture began to weaken. This was due to many years of drought, which means a long time without enough rain. By 1000 AD, the city of Wari had far fewer people. However, some groups who were descendants of the Wari still lived there. Buildings in Wari and other government centers had doorways that were purposely blocked. It was as if the Wari planned to return when the rains came back. But by then, the Wari had faded away. The remaining people in Wari cities stopped building anything big. Evidence shows that fighting and raids increased among different groups as the Wari government fell apart. The end of the Wari culture marked the start of the Late Intermediate Period in Peru.

Wari Government

Not much is known about the exact details of the Wari government. They did not seem to use a written language. Instead, they used a tool called khipu, or "knot record." Khipus were strings with knots used for counting and keeping records. While khipus are most famous for their use by the Inca, many experts believe the Wari were the first to use them for recording information.

Archaeologists also study the Wari's similar building styles in different areas. They also look at signs of different social classes. This helps them understand the complex system of leaders and social groups in Wari society.

In early 2013, an untouched royal tomb was found at El Castillo de Huarmey. This discovery gave new clues about the Wari's power and influence. The many different and valuable items buried with three royal women show that the Wari culture was very wealthy. It also shows they had the power to control a large part of northern coastal Peru for many years.

Another example of how burials help us understand social classes is in the city of Conchopata. This city is about 10 kilometers (6 miles) from the capital city. The remains of over 200 people have been found there. Before these discoveries, people thought Conchopata was mainly a city of potters. But the burials showed that servants, middle-class people, important leaders, and even local kings or governors lived in the city.

Wari Architecture

As the Wari state grew, it built special government centers in many of its regions. However, these centers often did not have a clear plan like many other ancient cities in the Andes. Wari buildings were different from those of Tiwanaku. Some experts believe Tiwanaku was a more loosely connected state.

Wari buildings were usually made of rough fieldstones. These stones were then covered in white plaster. The main buildings were often large, rectangular areas with no windows. They had only a few entrances. These sites also did not have a central place for people to gather for religious events. This is very different from Tiwanaku, which had more open spaces for many people to gather. A unique Wari building style was the use of D-shaped structures. These were often used as temples and were quite small, about 10 meters (33 feet) long.

The Wari used their government centers and temples to influence the areas around them. Experts have learned about Wari architecture by studying the Inca. Several Wari sites were found along the Inca highway system. This suggests that the Wari also used a similar network of roads. They also created new farmlands using terraced field technology. The Inca later got ideas from this as well.

Wari Social Life

Based on findings from many Wari sites, archaeologists believe that feasts and food offerings were very important in Wari social life. In the Cotocotuyoc region, many remains of camelids (like llamas or alpacas) have been found. These animals were not common in that area. This suggests they were used as a sign of social status and wealth.

Some camelid remains were found without cut marks and stacked on top of human bones. This makes researchers think they were not fully eaten on purpose. This was a way for the feast host to show off their wealth. This practice is known as ritual wasteful consumption.

Wari Religion

The Wari worshipped the Staff God. This was a main god in many Andean cultures. Some of the oldest pictures of the Staff God are found on Wari textiles and pottery. These images are thought to be over 3,000 years old. Some experts believe the Wari Staff God was an early version of the three main Inca gods: Sun, Moon, and Thunder.

The Wari also practiced animal sacrifice. Complete skeletons of a young camelid and thirty-two guinea pigs were found. They were buried in a "lineage house" in the city of Conchopata. This city is ten kilometers (6 miles) from the capital city of Wari. The fact that the remains were complete, and the age of the camelid, suggests the animals were sacrificed at the end of the rainy season in the Ayacucho valley.

Wari Art

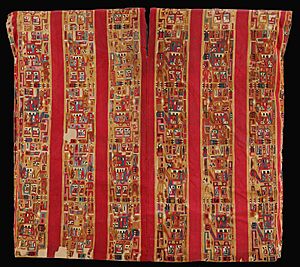

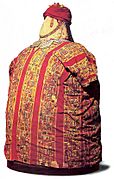

The Wari are especially known for their textiles (woven fabrics). These were well-preserved because they were buried in dry desert areas. The similar patterns on textiles show that the Wari government controlled how important art was made. Surviving textiles include tapestries, hats, and tunics (long shirts) for high-ranking officials. Each tunic could have between six and nine miles of thread. They often showed very abstract versions of typical Andean art patterns, like the Staff God. It is thought that these abstract designs might have been a "secret code" to keep out people who were not part of their group. The geometric shapes might also have made the wearer's chest look bigger, showing their high rank.

The Wari also made very detailed metalwork and ceramics (pottery). These often had similar designs to their textiles. The most common metals used were silver and and copper. Gold Wari items have also been found. Common metal objects included qiru (drinking cups), bowls, jewelry, masks for mummy bundles, pins for cloaks, and small metal figures. These figures show how the tunics were worn. Wari ceramics were usually colorful and often showed food and animals. Conchopata seems to have been a center for pottery making. Many pottery tools, firing rooms, pit kilns, potsherds (broken pottery pieces), and ceramic molds were found there. In one of the D-shaped temples at Conchopata, large broken chicha (corn beer) vessels were found on the floor. Special offerings were also made there.

Gallery

-

Four-cornered hat, 650–1000 AD, Brooklyn Museum

-

Wari tunic, Peru, 750–950 AD: This tunic is made of 120 separate small pieces of cloth, each individually tie-dyed. Ceramics of the period depict high-status men wearing this style of tunic.

-

Pikillaqta administrative center, built by the Wari civilization in Cusco

See also

In Spanish: Cultura wari para niños

In Spanish: Cultura wari para niños