Huni facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Huni |

|

|---|---|

| Ny-Suteh, Nisut-Hu, Hu-en-nisut, Qahedjet(?), Kerpheris, Aches | |

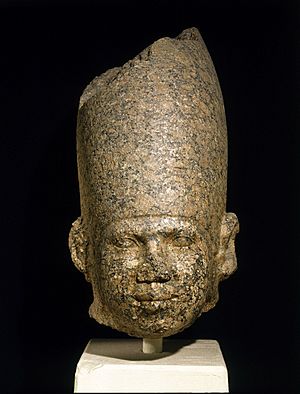

Pink granite head possibly depicting Huni, Brooklyn Museum

|

|

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign | 24 years (3rd Dynasty) |

| Predecessor | Khaba(?) |

| Successor | Sneferu |

| Consort | Djefatnebti(?), Meresankh I(?) |

| Children | Hetepheres I(?), Sneferu(?) |

| Monuments | Cultic step pyramid and palace at Elephantine |

Huni was an ancient Egyptian king. He was the last pharaoh of the Third Dynasty of Egypt during the Old Kingdom period. According to the Turin king list, he ruled for about 24 years, ending around 2613 BC.

Historians are quite sure Huni was the last king of his dynasty. However, they are still figuring out the exact order of rulers at the end of the 3rd dynasty. It's also unclear which Greek name the ancient historian Manetho used for him. Many experts believe Huni was the father and direct predecessor of King Sneferu, who started the next dynasty. But other scholars question this idea. Huni is a bit of a mystery in Egyptian history. People remembered him for a long time, but very few objects or buildings from his rule have survived.

Contents

Discoveries About Huni

Huni is not a pharaoh we know a lot about from direct evidence. Most of what we know comes from indirect clues. There are only two objects from his time that clearly show his name.

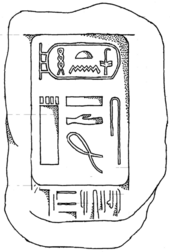

One important discovery is a cone-shaped stone made of red granite. It was found in 1909 on Elephantine island. This stone is about 63 inches (160 cm) long. It has a special carved area that mentions a royal palace called "Palace of the headband of Huni." Huni's name is written inside a royal cartouche (an oval shape enclosing a royal name). Experts think this carved area was like a "window" for showing off the king's name. The stone was found near a small stepped pyramid. This suggests it might have been placed at the front of the pyramid or even built into its steps. Today, you can see this cone at the Cairo Museum.

The second important discovery happened in 2007. It was a smooth stone bowl made of magnesite. This bowl was found at South-Abusir in a tomb belonging to an important official. The bowl has Huni's name on it, but without a cartouche. Instead, it uses the Njswt-Bity title, which means "King of Upper and Lower Egypt."

Huni is also mentioned in a tomb at Saqqara. This tomb belonged to an official named Metjen. An inscription there talks about a royal estate of Huni called "Hut-nisut-hu."

His name also appears on the back of the Palermo Stone. This stone mentions that King Neferirkare Kakai from the 5th dynasty built a temple to honor Huni. However, this temple has not been found yet.

Finally, Huni is mentioned in the Papyrus Prisse, a very old document. Many scholars believe this papyrus helps support the idea that Huni was the last king of the 3rd dynasty. They think he was the direct predecessor of King Sneferu, who was the first ruler of the 4th dynasty.

Huni's Name and Identity

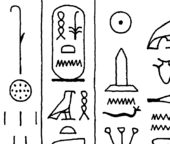

It's tricky to be sure about Huni's identity because his name appears in different ways. His name is usually written inside a cartouche. The oldest possible mention of his cartouche name is on the granite cone from Elephantine. Other early mentions are on the Palermo Stone and the Prisse Papyrus. Huni's name also appears in later king lists, like the Saqqara King List and the Turin Canon. However, the Abydos King List, another old record, strangely leaves out Huni's name. Instead, it lists a king named Neferkara I, who is unknown to historians.

The way Huni's name is read and translated is also debated. There are two main versions of his name: an older one, which is probably closer to the original, and a newer one from much later times.

The older version of his name uses hieroglyphs that look like a candle wick, a rush sprout, a bread loaf, and a water line. This way of writing is found on old objects like the Palermo Stone and the granite cone. These older writings usually put his name inside an oval cartouche.

Later versions of his name, from the Ramesside period (much later in Egyptian history), use different hieroglyphs. These include a candle wick, a beating man, a water line, and an arm with a stick. Experts believe that scribes from the Ramesside period might have misunderstood the older hieroglyphs. For example, they might have confused the "juncus sprout" sign with something else. They also might have thought the candle wick meant "smiting," which led them to add the "beating man" hieroglyph.

Historians today generally agree that both the old and new versions of the name refer to the same king.

Huni's Possible Horus Name

We don't know Huni's Horus name for sure. The Horus name was another important name for Egyptian kings, often linked to the god Horus.

Some experts, like Toby Wilkinson and Rainer Stadelmann, think Huni might be the same king as Horus-Khaba. Khaba's name appears on many stone vessels from that time. This idea is based on how kings' names were written on stone vessels during the 3rd dynasty. Stadelmann also points to the Layer Pyramid at Zawyet el'Aryan. This pyramid might have been built by Khaba. Since the Turin Canon says Huni ruled for 24 years, Stadelmann believes this long reign would have been enough time to finish the Layer Pyramid. He also notes that many objects with Khaba's name have been found across Egypt, suggesting a long rule. Because of these reasons, he believes Khaba and Huni could be the same person.

Huni's Family

Huni's family connections are a bit unclear. Ancient documents often mention Huni and his successor, Sneferu, one after the other. This makes historians think they might have been related. Queen Meresankh I, who was Sneferu's mother, was definitely a queen. However, no records directly say she was Huni's daughter or wife. This makes the family link between Huni and Sneferu uncertain. Most scholars today tend to believe the historian Manetho, who wrote that a new royal family took power when Sneferu became king, starting a new dynasty.

One possible wife of Huni was Queen Djefatnebti. Her name was found in black ink on beer jars from Elephantine. She had the title "great one of the hetes-sceptre," which means she was a queen. One expert, Günter Dreyer, thinks that the jars mention Djefatnebty's death during Huni's reign, possibly in his 22nd year. However, not everyone agrees with this idea.

So far, no children or other relatives of Huni have been clearly identified. Some historians, like William Stevenson Smith, have suggested that Queen Hetepheres I (Sneferu's wife and mother of King Khufu) might have been Huni's daughter. Hetepheres had the title "Daughter of a God." Smith thought this could mean she was Huni's daughter. If so, marrying Sneferu would have helped keep the royal family line going. But other scholars disagree, saying her title doesn't clearly state who she was married to.

Huni's Reign

We know very little about what happened during Huni's time as king. The Turin canon says he ruled for 24 years, and most scholars accept this. We don't have any records of religious events or military battles from his reign.

However, we do have tomb inscriptions from important officials like Metjen. These inscriptions are from the end of the 3rd dynasty and the start of the 4th dynasty. They suggest that Huni's reign was the beginning of a great period for the Old Kingdom. For the first time, these writings show how the government was structured. They mention important officials like nomarchs (governors of regions) and viziers (high-ranking ministers) having a lot of power. Metjen's tomb also mentions that important official and priestly titles were passed down from father to son. This was a new development in Egyptian history.

It seems Huni also started some building projects. The Turin Canon, which usually doesn't give many details, says Huni built a certain structure. Unfortunately, the papyrus is damaged, and the full name of the building is lost. Some Egyptologists think it might have been part of a larger project to build several small cultic pyramids across the land.

Another clue about Huni's building projects might be in the name of the ancient city of Ehnas (now known as Heracleopolis Magna). One scholar, Wolfgang Helck, points out that the Old Kingdom name of this city, Nenj-niswt, was written with the same hieroglyphs as Huni's name. This suggests Huni might have founded Ehnas.

After his death, Huni seems to have been remembered for a long time. The Palermo Stone, made over a hundred years after Huni died, mentions gifts given to a temple built for Huni's memory. His name also appears in the Prisse Papyrus, written much later during the 12th dynasty. This shows that Huni was remembered long after his rule.

Monuments Possibly Connected to Huni

Meidum Pyramid

In the early 1900s, many people thought the Meidum pyramid was started by Huni. The idea was that Huni began building a stepped pyramid, like those of earlier kings. Then, when King Sneferu took over, he supposedly covered it with smooth limestone to make it a "true pyramid." The pyramid's unusual look was sometimes blamed on a building disaster where the outer layers collapsed. This theory seemed to make sense because historians at the time didn't think Sneferu ruled long enough to build three pyramids by himself.

However, closer studies of the area around the pyramid changed this idea. Many tomb inscriptions and visitor writings were found praising "the beauty of the white pyramid of King Sneferu." They also asked for prayers for Sneferu and his wife, Meresankh I. Also, the tombs around the pyramid date to Sneferu's reign, not Huni's. Huni's name has never been found near the Meidum pyramid.

These clues led experts to believe that the Meidum pyramid was never Huni's. Instead, it was built by Sneferu, possibly as a special monument for himself. Later writings show that the white limestone covering was still there during the 19th dynasty. This means it started to collapse slowly after that time. People also took limestone from the pyramid over many centuries to use for other buildings.

Another reason against the idea that Sneferu finished Huni's project is new information about Sneferu's reign. The Turin Canon says Sneferu ruled for 24 years. But during the Old Kingdom, years were often counted every two years (when cattle counts and tax collections happened). This means Sneferu might have actually ruled for 48 years! If he ruled for 48 years, he would have had plenty of time to build three pyramids during his lifetime. Also, experts point out that kings in the Old Kingdom usually didn't take over or finish the tombs of earlier rulers. A new king would simply bury and seal the tomb of his predecessor.

Layer Pyramid

As mentioned before, some historians like Rainer Stadelmann believe Huni might have built the Layer Pyramid at Zawyet el'Aryan. This pyramid was almost finished when it was abandoned. We don't know if the underground burial chambers were ever used for a king. A nearby tomb (Mastaba Z500) that was part of the pyramid complex contained several stone bowls with the Horus name of King Khaba. Because of this, the Layer Pyramid is often called the pyramid of Khaba. Rainer Stadelmann suggests that Khaba and Huni are the same person. He argues that building the pyramid would have taken a long time, and Huni's 24-year reign would have been enough to complete it. So, both names ("Huni" and "Khaba") might refer to the same ruler.

Cultic Step Pyramids

Several small step pyramids along the Nile River are also thought to be connected to Huni. These small pyramids were used for religious purposes and marked important royal lands. They didn't have any rooms inside and were not used for burials. One of these pyramids is on the eastern side of Elephantine island. A granite cone with Huni's name was found nearby in 1909. Because of this, this small pyramid is the only one that might be linked to Huni with some certainty. However, some scholars disagree, saying that Huni's granite cone might have been moved there later. The only small cultic step pyramid that is definitely linked to an Old Kingdom ruler is the Seila Pyramid near the Faiyum Oasis. Two large stones with Sneferu's name were found there, showing he built it. Since Sneferu was likely Huni's successor, this suggests that these types of cultic pyramids were indeed built around the time the 3rd and 4th dynasties changed.

Huni's Burial Place

We still don't know where Huni was buried. Since the Meidum pyramid is now thought to be Sneferu's, experts have suggested other possible burial sites for Huni. As mentioned, Rainer Stadelmann and Miroslav Verner believe the Layer Pyramid at Zawyet el-Aryan could be Huni's tomb. This is because they think Huni and Khaba are the same king, and Khaba is strongly linked to the Layer Pyramid.

Alternatively, Stadelmann suggests a very large tomb (mastaba) at Meidum, called M17, as Huni's burial place. This mastaba was huge, about 330 feet (100 meters) long and 660 feet (200 meters) wide. It was built from mud bricks and filled with rubble. Inside, there was a deep shaft leading to a corridor and several chapels. The burial chamber was robbed long ago, and everything inside was destroyed or stolen. The large stone coffin contained the remains of a mummy that had been badly damaged. Stadelmann thinks this mastaba was either the tomb of a crown prince who died before becoming king, or it was Huni's own burial place.

Miroslav Bárta suggests that mastaba AS-54 in South-Abusir is the most likely burial site for Huni. This is supported by the discovery of the polished magnesite bowl with Huni's niswt-bity title. The mastaba itself was once very large and had many rooms. It also contained many polished dishes, vases, and urns. However, almost all these vessels were plain, with no ink inscriptions or carvings. So, the name of the true owner is still unknown. Only one vessel clearly shows Huni's name, while a few others might have faint traces. Bárta believes the owner of the mastaba was either a very important official, like a prince from Huni's time, or King Huni himself.

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Huny para niños

In Spanish: Huny para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |