Ian Stevenson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ian Stevenson

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | October 31, 1918 Montreal, Quebec, Canada

|

| Died | February 8, 2007 (aged 88) Charlottesville, Virginia, United States

|

| Citizenship | Canadian by birth; American, naturalized 1949 |

| Education | University of St. Andrews (1937–1939) BSc (McGill University, 1942) MD (McGill University School of Medicine, 1943) |

| Occupation | Psychiatrist, director of the Division of Perceptual Studies at the University of Virginia School of Medicine |

| Known for | Reincarnation research, near death studies, medical history taking |

| Spouse(s) | Octavia Reynolds (m. 1947) Margaret Pertzoff (m. 1985) |

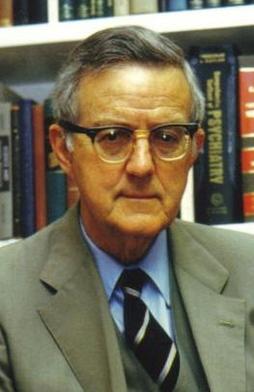

Ian Pretyman Stevenson (October 31, 1918 – February 8, 2007) was a Canadian-born American psychiatrist. He was famous for his research into reincarnation. This is the idea that a person's memories, feelings, and even physical features might pass into a new body after death.

Stevenson worked as a professor at the University of Virginia School of Medicine for 50 years. He led the psychiatry department from 1957 to 1967. Later, he became a research professor until he passed away in 2007.

He started and directed the Division of Perceptual Studies at the University of Virginia. This group studies unusual or paranormal events. Stevenson became known for looking into cases that seemed to suggest reincarnation. He spent 40 years traveling the world. He studied about 3,000 cases of children who said they remembered past lives.

Stevenson believed that some fears, special skills, or illnesses couldn't be fully explained by genes or environment. He thought reincarnation might be a third reason for these things.

He helped create the Society for Scientific Exploration in 1982. He wrote many books and articles about reincarnation. Some of his well-known books include Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation (1966) and Where Reincarnation and Biology Intersect (1997). This last book looked at 200 cases where birthmarks or birth defects seemed to match wounds on a person the child claimed to have been in a past life.

People had different opinions about his work. Some thought he was a genius who was misunderstood. Others thought he was honest but too easily fooled. Most scientists, however, didn't pay much attention to his research. His work is still studied by others, like Jim B. Tucker, a psychiatrist who now leads the division Stevenson started.

Contents

About Ian Stevenson

His Early Life and School

Ian Stevenson was born in Montreal, Canada. He grew up in Ottawa. His father was a lawyer from Scotland. His mother, Ruth, was interested in Theosophy, which is a spiritual philosophy. She had many books on the subject. Stevenson said this sparked his early interest in the paranormal.

As a child, he often had bronchitis and had to stay in bed. This made him love reading books. He kept a list of all the books he read. By 2003, he had read 3,535 books!

He studied medicine in Scotland from 1937 to 1939. But he had to finish his studies in Canada because of World War II. He earned his science degree in 1942 and his medical degree in 1943 from McGill University.

He married Octavia Reynolds in 1947. She passed away in 1983. In 1985, he married Dr. Margaret Pertzoff. She was a history professor. She didn't share his beliefs about the paranormal. But Stevenson said she was "benevolently silent" about them.

Starting His Career

After medical school, Stevenson first did research in biochemistry. But he had lung problems, so he moved to Arizona for his health. He worked in hospitals in Phoenix and New Orleans. He also studied at Cornell University. He became a U.S. citizen in 1949.

Stevenson became unhappy with how biochemistry focused only on tiny parts of the body. He wanted to study the whole person. He became interested in psychosomatic medicine, which looks at how the mind affects the body. He also studied psychiatry. He wanted to understand why stress caused different illnesses in different people.

From 1949 to 1957, he taught psychiatry at Louisiana State University School of Medicine. He also studied psychoanalysis. He became the head of the psychiatry department at the University of Virginia in 1957. He often disagreed with common ideas in psychiatry. This prepared him for how people would react to his later work on the paranormal.

Researching Reincarnation

How His Interest Began

Stevenson said his main goal was to understand why one person got one disease and another got a different one. He thought that genes and environment couldn't explain certain fears, illnesses, or special talents. He believed that some kind of personality or memory transfer might be a third explanation.

He knew there was no proof of how a personality could survive death and move to another body. He was careful not to say for sure that reincarnation happens. He only argued that his cases couldn't be explained by normal reasons. He felt that "reincarnation is the best – even though not the only – explanation for the stronger cases we have investigated."

In the late 1950s, Stevenson wrote articles about parapsychology, which is the study of mental abilities beyond normal ones. He won a prize for an essay about "paranormal mental phenomena." This essay looked at 44 cases of people, mostly children, who said they remembered past lives.

A woman named Eileen J. Garrett gave Stevenson a grant. This allowed him to travel to India to interview a child who claimed to remember a past life. He found 25 more cases in just four weeks! This led to his first book on the topic, Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation, published in 1966.

Support for His Work

Chester Carlson, who invented the Xerox machine, offered more money to support Stevenson's work. This allowed Stevenson to step down from his role as department chair. He then created a special group within the psychiatry department. It was first called the Division of Personality Studies, and later the Division of Perceptual Studies.

When Carlson died in 1968, he left $1,000,000 to the University of Virginia for Stevenson's research. Some people at the university were unsure about accepting the money because of the unusual nature of the research. But the donation was accepted. Stevenson became the first Carlson Professor of Psychiatry.

His Case Studies

Looking at Past Life Memories

The money from Chester Carlson allowed Stevenson to travel a lot. He sometimes traveled as much as 55,000 miles a year. He collected about 3,000 case studies. He interviewed children from places like Africa and Alaska.

In one case, a baby girl in Sri Lanka would scream near a bus or a bath. When she could talk, she said she remembered being a girl who drowned after a bus pushed her into a flooded rice field. Later, Stevenson found the family of a girl who had died that way, just a few miles away. The two families were not known to each other.

A journalist named Tom Shroder said that Stevenson always looked for other explanations. He checked if the child learned the information normally. He also checked if people were lying or fooling themselves. But in many cases, Stevenson concluded that no normal explanation could explain what he found.

Birthmarks and Birth Defects

In some cases, children who remembered past lives had birthmarks or birth defects. These marks sometimes matched wounds on the person the child claimed to have been. Stevenson's book, Reincarnation and Biology: A Contribution to the Etiology of Birthmarks and Birth Defects (1997), looked at 200 such cases.

For example, he studied children with missing or badly formed fingers. These children said they remembered the lives of people who had lost fingers. He also studied a boy with birthmarks that looked like bullet entry and exit wounds. The boy said he remembered being someone who had been shot. Another child had a scar-like mark around her head. She said she remembered being a man who had brain surgery. In many of these cases, Stevenson found witness statements or autopsy reports that seemed to support the idea that the deceased person had similar injuries.

Xenoglossy Research

Stevenson mostly studied children remembering past lives. But he also looked at two cases where adults, while under hypnosis, seemed to remember a past life. They also showed a basic ability to use a language they had not learned in their current life. Stevenson called this "xenoglossy."

However, some experts, like linguist Sarah Thomason, criticized these cases. She said Stevenson didn't know enough about language. She concluded that the language evidence was too weak to prove xenoglossy. Another linguist, William J. Samarin, said Stevenson didn't talk to linguists in a professional way. He felt Stevenson didn't consider enough language evidence to support his ideas.

Later Years and Legacy

Ian Stevenson retired as the director of the Division of Perceptual Studies in 2002. But he kept working as a research professor. Bruce Greyson became the new director of the division. Jim B. Tucker, another psychiatrist, continued Stevenson's research with children. Tucker wrote a book about it called Life Before Life: A Scientific Investigation of Children's Memories of Previous Lives (2005).

Stevenson passed away from pneumonia on February 8, 2007, in Virginia. In his will, he left money to McGill University to create a special teaching position in philosophy and history of science.

As an experiment, Stevenson set a combination lock in the 1960s. He used a secret word or phrase. He told his colleagues he would try to send them the code after he died. Emily Williams Kelly, a colleague, explained that if someone had a very clear dream about him with a repeated word or phrase, they would try to use it to open the lock.

Books by Ian Stevenson

- (1960). Medical History-Taking. Paul B. Hoeber.

- (1966). Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation. University of Virginia Press.

- (1969). The Psychiatric Examination. Little, Brown.

- (1970). Telepathic Impressions: A Review and Report of 35 New Cases. University Press of Virginia.

- (1971). The Diagnostic Interview (2nd revised edition of Medical History-Taking). Harper & Row.

- (1974). Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation (second revised and enlarged edition). University of Virginia Press.

- (1974). Xenoglossy: A Review and Report of A Case. University of Virginia Press.

- (1975). Cases of the Reincarnation Type, Vol. I: Ten Cases in India. University of Virginia Press.

- (1978). Cases of the Reincarnation Type, Vol. II: Ten Cases in Sri Lanka. University of Virginia Press.

- (1980). Cases of the Reincarnation Type, Vol. III: Twelve Cases in Lebanon and Turkey. University of Virginia Press.

- (1983). Cases of the Reincarnation Type, Vol. IV: Twelve Cases in Thailand and Burma. University of Virginia Press.

- (1984). Unlearned Language: New Studies in Xenoglossy. University of Virginia Press.

- (1987). Children Who Remember Previous Lives: A Question of Reincarnation. University of Virginia Press.

- (1997). Reincarnation and Biology: A Contribution to the Etiology of Birthmarks and Birth Defects. Volume 1: Birthmarks. Praeger Publishers.

- (1997). Reincarnation and Biology: A Contribution to the Etiology of Birthmarks and Birth Defects. Volume 2: Birth Defects and Other Anomalies. Praeger Publishers.

- (1997). Where Reincarnation and Biology Intersect. Praeger Publishers (a short, non-technical version of Reincarnation and Biology).

- (2000). Children Who Remember Previous Lives: A Question of Reincarnation (revised edition). McFarland Publishing.

- (2003). European Cases of the Reincarnation Type. McFarland & Company.

- (2019). Handbook of Psychiatry volume Five (Co-written with Javad Nurbakhsh and Hamideh Jahangiri). LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

- (2020). Psychological Treatment Techniques For Social Anxiety Disorder (Co-written with Aliakbar Shoarinejad and Hamideh Jahangiri). Scholars' Press.

Selected Articles by Ian Stevenson

- (1949). "Why medicine is not a science", Harper's, April.

- (1952). "Illness from the inside", Harper's, March.

- (1952). "Why people change", Harper's, December.

- (1954). "Psychosomatic medicine, Part I", Harper's, July.

- (1954). "Psychosomatic medicine, Part II", Harper's, August.

- (1957). "Tranquilizers and the mind", Harper's, July.

- (1957). "Schizophrenia", Harper's, August.

- (1957). "Is the human personality more plastic in infancy and childhood?", American Journal of Psychiatry, 114(2), pp. 152–161.

- (1958). "Scientists with half-closed minds" Harper's, November.

- (1959). "A Proposal for Studying Rapport which Increases Extrasensory Perception," Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 53, pp. 66–68.

- (1959). "The Uncomfortable Facts about Extrasensory Perception", Harper's, July.

- (1960). "The Evidence for Survival from Claimed Memories of Former Incarnations," Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 54, pp. 51–71.

- (1960). "The Evidence for Survival from Claimed Memories of Former Incarnations": Part II. Analysis of the Data and Suggestions for Further Investigations, Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 54, pp. 95–117.

- (1961). "An Example Illustrating the Criteria and Characteristics of Precognitive Dreams," Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 55, pp. 98–103.

- (1964). "The Blue Orchid of Table Mountain," Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 42, pp. 401–409.

- (1968). "The Combination Lock Test for Survival," Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 62, pp. 246–254.

- (1970). "Characteristics of Cases of the Reincarnation Type in Turkey and their Comparison with Cases in Two other Cultures," International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 11, pp. 1–17.

- (1970). "A Communicator Unknown to Medium and Sitters," Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 64, pp. 53–65.

- (1970). "Precognition of Disasters," Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 64, pp. 187–210.

- (1971). "The Substantiability of Spontaneous cases," Proceedings of the Parapsychological Association, No. 5, pp. 91–128.

- (1972). "Are Poltergeists Living or Are They Dead?," Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 66, pp. 233–252.

- (1977). Stevenson, IAN (May 1977). "The Explanatory Value of the Idea of Reincarnation". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 164 (5): 305–326. doi:10.1097/00005053-197705000-00002. PMID 864444.

- (1983). Stevenson, I. (Dec 1983). "American children who claim to remember previous lives". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 171 (12): 742–748. doi:10.1097/00005053-198312000-00006. PMID 6644283.

- (1986). Stevenson, I. (1986). "Characteristics of Cases of the Reincarnation Type among the Igbo of Nigeria". Journal of Asian and African Studies 21 (3–4): 204–216. doi:10.1177/002190968602100305. http://jas.sagepub.com/content/21/3-4/204.

- (1993). "Birthmarks and Birth Defects Corresponding to Wounds on Deceased Persons". Journal of Scientific Exploration 7 (4): 403–410. https://www.scientificexploration.org/docs/7/jse_07_4_stevenson.pdf.

- with Emily Williams Cook and Bruce Greyson (1998). "Do Any Near-Death Experiences Provide Evidence for the Survival of Human Personality after Relevant Features and Illustrative Case Reports". Journal of Scientific Exploration 12 (3): 377–406. https://med.virginia.edu/perceptual-studies/wp-content/uploads/sites/360/2017/01/STE46_Do-Near-Death-Experiences-Provide-Evidence-for-Survival-of-Human-Personality.pdf.

- (1999). Stevenson, I. (Apr 1999). "Past lives of twins". Lancet 353 (9161): 1359–1360. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74353-1. PMID 10218554.

- (2000). Stevenson, I. (Apr 2000). "The phenomenon of claimed memories of previous lives: possible interpretations and importance". Medical Hypotheses 54 (4): 652–659. doi:10.1054/mehy.1999.0920. PMID 10859660. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/e8d778d20507be2d971858ffeac47ad455c6ad95.

- (2000). Stevenson, I. (1985). "The Belief in Reincarnation Among the Igbo of Nigeria". Journal of Asian and African Studies 20 (1–2): 13–30. doi:10.1177/002190968502000102. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-72763292.html.

- (2001). Stevenson, I. (August 2001). "Ropelike birthmarks on children who claim to remember past lives". Psychological Reports 89 (1): 142–144. doi:10.2466/pr0.2001.89.1.142. PMID 11729534. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/6ebdd2a6cd6b255a0e3378ed168b32b3521d5df6.

- with Satwant K. Pasricha; Jürgen Keil; and Jim B. Tucker (2005). "Some Bodily Malformations Attributed to Previous Lives". Journal of Scientific Exploration 19 (3): 159–183. https://med.virginia.edu/perceptual-studies/wp-content/uploads/sites/360/2016/12/REI34.pdf.

- (2005). Foreword and afterword in Mary Rose Barrington and Zofia Weaver. A World in a Grain of Sand: The Clairvoyance of Stefan Ossowiecki. McFarland Press.

An extended list of Stevenson's works is online here: http://www.pflyceum.org/167.html

See also

In Spanish: Ian Stevenson para niños

In Spanish: Ian Stevenson para niños

- Parapsychology

- Afterlife

- Near-death experiences

- Richard Wiseman

- Xenoglossy

- Philosophy

- Dualism (philosophy of mind)

- Explanatory gap

- Hard problem of consciousness

- Mind–body problem

- Mysterianism

- Qualia